The news from Afghanistan has been gloomy of late, with constant questions being asked in Britain about why – and for what – so many of their soldiers are dying. Every week in the UK we see images of families receiving coffins, or read the words of a widow whose mourning is pinched by doubts about what a loved one has died for.

Politicians want a way out of this quagmire. So talking to the Taliban is back on the table, a discussion that quickly leads to clumsy distinctions about varieties of Taliban. David Miliband wants to distinguish between those who want local Islamic rule (OK), versus those who want global jihad (no way). "Old style Taliban" is a phrase sometimes used – presumably those like good old Mullah Omar, who may have only wanted his extreme view of Islam enforced on his unwilling country, not the world.

But governments need to come clean with what this may all mean for Afghan women, who have not forgotten the promises made by British and US officials that troops were coming in part to liberate them from Taliban oppression. Over the past few months in Kabul, women's rights activists have been discussing what deals with the Taliban would mean for the fledgling gains they've won – freedom to work, study, to get healthcare, run for parliament. They are scared – particularly because this comes at a time when the fundamentalists are growing in strength in government, too.

The Afghan Parliament is controlled by a generation of current and former warlords whose views are not so different from those of the Taliban. Men like Abdul Rasul Sayyaf – one of the most powerful politicians in Afghanistan, who dominates parliament and has the ear of President Hamid Karzai. He, rather than the Taliban, may have been the person who first invited Osama bin Laden to Afghanistan.

Earlier this year, this parliament, and the president, passed into law legislation that denied Shia women some of their most basic human rights. This includes giving rights to husbands to withhold basic maintenance (food) if a wife does not meet his sexual demands. When women parliamentarians try to fight legislation like this new Shia law they receive threats and intimidation – including from fellow MPs. They get little support from the president, who signed the law in exchange for the promise of votes from fundamentalist Shia leaders in next month's presidential election. When the president is willing to sell out for a few votes, women have reason to be worried. If deals are made with the Taliban this could be the tipping point, the final unravelling for Afghan women and girls.

When I ask diplomats what deals with the Taliban will mean for women, I usually get platitudes about commanders being made to "sign up to the constitution", as if that alone might winkle out those secretly intent on shutting down girls' schools or banning women from working, as the Taliban did when they were in power. Or I get a realpolitik brush-off about how foreigners need to accept that Afghanistan is an inherently conservative country – code for saying that women's rights are not universal, that the accident of birth is grounds for relegating them to discrimination and abuse.

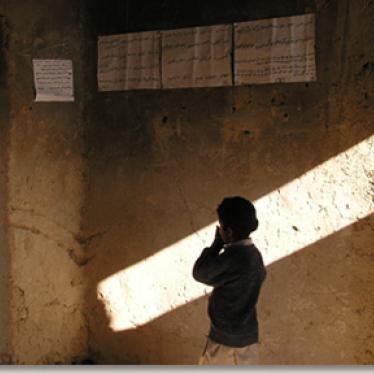

The irony is that these diplomats are talking about the past. Almost half the population is under 15. Not many of the teenagers I've met in the two years I've lived in Kabul share the ideology of their rulers. They are often observant Muslims, but their passions are for getting an education, getting their hands on the latest Hindi-pop ringtone, or getting out of the country.

So talk with your enemy if you want. Make deals to end fighting if you think it is wise. But don't sell out Afghan women and young people in the process. For a politician who wants to do a deal with the Taliban the test is not the constitution, it is whether they can look an Afghan woman in the eye as they do so and tell them that the price will not be a life of second-class citizenship for them and their daughters.

Rachel Reid is Afghanistan researcher for Human Rights Watch.