As presidential elections approach, Congo’s tens of thousands of street children risk political manipulation and physical harm, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

In recent years, leaders of political parties have enlisted street children to create public disorder in mass demonstrations. In many cases, the security forces have responded to these protests with excessive use of force, leading to the death and injury of dozens of children.

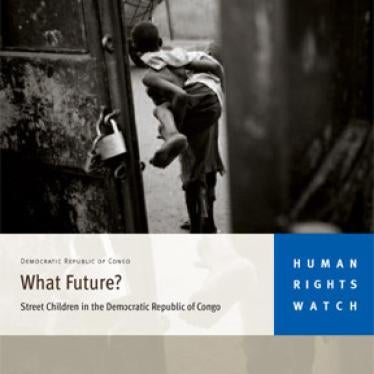

The 72-page report, “What Future? Street Children in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” documents how security officials and other adults routinely abuse the country’s street children. In the past 10 years, armed conflict, HIV/AIDS, prohibitive education fees, and even accusations of sorcery have led to a doubling of the number of street children. With no secure access to shelter, food or other basic needs, these children live in insecurity and fear.

Instead of providing street children with protection, police and soldiers routinely use physical violence and threats of arrest to steal from these children. Street children also face physical and sexual abuse at the hands of adults and older youth, who take advantage of their vulnerable status. Rape of both girls and boys is pervasive.

“As a first step, the Congolese government must protect street children during the election period. U.N. agencies in Congo should redouble their efforts to prevent abuse,” said Tony Tate, Africa children’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch and the author of the report. “Congolese authorities should use this opportunity to start addressing the abuses committed against children.”

The Congolese government periodically orders mass roundups of street children, justifying their detention on the basis of a colonial-era law that forbids children from begging. Guilty of nothing more than being without a home, large groups of children are detained and held in overcrowded jails, often mixed with adult prisoners. Held for days in deplorable conditions, these children are usually released without being charged, and then put back on the street.

“Congolese authorities should be assisting homeless children, not throwing them in jail,” said Tate. “The government should end roundups of street children and do away with laws that criminalize children for being homeless.”

In an alarming trend, an increasing number of children are being accused of sorcery, even though such accusations are specifically prohibited by Congo’s new constitution. Orphans or children living with step-parents are particularly vulnerable to accusations, made by their surviving relatives, that they are sorcerers responsible for the family’s misfortunes. Accused children are often neglected, abused, and thrown out of their homes.

Agencies that work with children in Kinshasa estimate that as many as 70 percent of the city’s street children had been accused of sorcery before they ended up on the street.

Specialized pastors or prophets from “churches of revival” perform ceremonies to rid children of their sorcery. In many such churches, dozens of children can be held for days at a time, with food and water denied. In the worst cases, children are whipped, beaten or given purgatives until they confess to sorcery. Even after the process is concluded, however, children can be subjected to further abuse at home, and ultimately abandonment.

“Congo’s new constitution expressly prohibits accusing children of sorcery,” said Tate. “Congolese authorities must take action against adults who mistreat children.”

Children affected by HIV/AIDS are particularly susceptible to accusations of sorcery. In the belief that HIV can be transmitted through sorcery, family members sometimes blame children for causing the death of their parents from AIDS. Already AIDS orphans, these children become double victims of the epidemic. National HIV/AIDS prevention campaigns must educate the Congolese public about the causes of HIV/AIDS and refute the view that it can be transmitted through sorcery.

Testimonies from the report:

“Our worry is this, what will become of these kids tomorrow? Thousands of children living on the streets with no supervision, no education, no love or care, accustomed to daily violence and abuse. What future for these children and for our country?”

– Street child educator in Lubumbashi

“Life is hard here in the streets, we are all the time harassed by the military. They come at night, any time after 10:00 p.m. They beat us with their hands or kick us with their boots. They regularly demand money or items they can sell... only those who run away and don’t get caught are safe. If we have worked all day for 100 francs they can even take that.”

– Emmanuel, 14-year-old street boy in Goma

“A few kids were stealing from the market, and the police arrested a whole group of street kids in the area. We were more than 20 kids in one small room at the lockup. We were whipped with a plastic cord on the buttocks. The kids would cry and scream. My friends paid the police 400 francs to make them stop, I was released that day.”

– Rebecca, 17-year-old street girl in Goma

“Sometimes men come and take me by force and afterwards, leave me no money. That happens often... I started this work when I was 10 years old. It is not a good life. I would rather go somewhere else and study.”

– Amelie, 15-year-old street girl in Lubumbashi

“I began spending more and more time away from the house at the compound of a church nearby. My brother found me there one day and beat me severely with his fists, telling me to leave the neighborhood. The pastor there told my brother to stop the beating, but seemed to believe him that I was a sorcerer and made me leave the church. I had no choice but to go to the streets.”

– Albert, a 10-year-old former street boy in Mbuji-Mayi

“We were not allowed to eat or drink for three days [either at church or at home]. On the fourth day, the prophet held our hands over a candle, to get us to confess.”

– Brian, 12, street child accused of sorcery in Kinshasa

“Child sorcerers have the power to transmit any disease, including AIDS, to their family members. AIDS is a mysterious disease that is used as a weapon by those who practice witchcraft.”

– Prophet who specializes in child sorcery at a revival church in Mbuji-Mayi