I am grateful to the Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs for affording me this opportunity to appear before you. In addition to my academic work as a specialist in Tibetan Studies, I have also served for some time as a consultant to Human Rights Watch. Most recently, I collaborated with Human Rights Watch on a new book, Tibet Since 1950: Silence, Prison, or Exile (published with Aperture Foundation) graphically detailing the reality of exile from Tibet today and the role that human rights violations play in forcing many Tibetans to leave their homeland. It is as a representative of Human Rights Watch that I address this Subcommittee.

I am here today to speak to Human Rights Watch's concerns about human rights conditions in Tibet. Tibet has been, for more than a decade, a place where some of the most visible and egregious human rights violations committed by the Chinese state have occurred. It is well known that Tibetan nationalism forms the background to this situation. Human Rights Watch does not endorse any particular political arrangement to resolve the issue of Tibet, but we do advocate that the right of all Tibetans to peacefully articulate and express themselves on political questions must be respected under existing and future political arrangements, whatever they may be.

Since 1987, Human Rights Watch has monitored and reported extensively on abuses that have transpired in Tibet. In general, we are pleased to note, greater attention is now being paid by the United States government to the situation in Tibet; for example, human rights violations there are now given significant exposure in the State Department's annual review of international human rights conditions.

Unfortunately, however, gross violations of human rights remain a continuing fixture of the situation in Tibet, in spite of the efforts of various concerned governments--including the U.S.--and NGOs to focus attention on the problem. It is crucial, therefore, that measures for putting effective pressure on China to adhere to recognized international human rights norms be included as a key component of U.S. policy towards China and be built into legislation governing U.S. relations with China.

In my testimony I will briefly describe several areas of continuing human rights violations in Tibet that are of particular concern to Human Rights Watch.

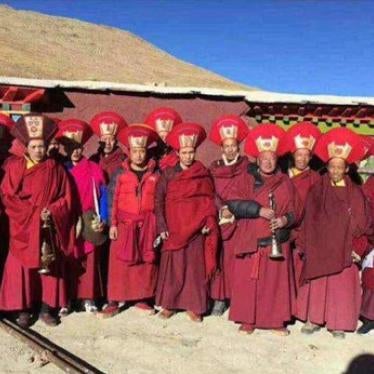

One of our concerns is continuing violations of religious freedom and the implementation by the Chinese government of policies aimed at subordinating religious practices and sentiments to serve the political needs of the state. This is not just a question of propaganda and persuasion. Rather, these policies impinge upon the freedom of many Tibetans to peacefully put into practice or even express certain key aspects of their religious beliefs; and they are implemented through the use of coercion, violent repression, and imprisonment. Particularly prominent in this regard has been the ongoing campaign of "patriotic education," aimed at undermining and eliminating the Dalai Lama's influence in Tibet. But there has also been an increasingly heavy-handed turn by the Chinese authorities towards putting certain monasteries and temples under secular, government-backed management in order to implement greater government control of Tibetan religion.

Such policies are closely tied to the well-known case of Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, the child whom the Dalai Lama formally recognized as the incarnation of the Panchen Lama. This child has been subjected to virtual house arrest for the last five years simply because most Tibetans have accepted him as the incarnation of the Panchen Lama and rejected the child whom the Chinese government named as Panchen Lama. Neither he nor his family have freedom of movement.

I will also discuss disturbing evidence that torture of prisoners in Tibet continues, in a number of cases resulting in death in custody. Torture has become entrenched in Tibet as part of the price that political activists must pay.

|

Finally, I would like to draw upon our new book Tibet Since 1950: Silence, Prison or Exile for a case study which illustrates what the effects of human rights abuses can be in one individual's life. Making Religion Serve Politics The issues of the Panchen Lama and "patriotic education" are closely bound up with each other, since it was the Dalai Lama's announcement of the recognition of the incarnation of the 11th Panchen Lama that precipitated the campaign of "patriotic education." When the Dalai Lama formally recognized the Panchen Lama in May 1995, the Chinese authorities reacted by virulently denouncing him and by taking harsh measures against the child whom he had recognized. The boy and his family have been kept in effective isolation from the outside world, and government representatives and human rights monitors have not been allowed independently to verify their conditions, in spite of many attempts to do so. Those who have tried to visit him in the five years since he was spirited away include Mary Robinson, the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights; Harold Koh, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor; and, most recently, Raymond Chan, the Canadian Secretary of State for Asia and the Pacific, who tried to see the child earlier this month. In all cases the requests were rebuffed; China simply states that the child is in good health but will allow no independent verification of that statement. In December 1995, China enthroned its own choice as Panchen Lama. The Panchen Lama is generally considered to be just below the Dalai Lama in stature within their particular sect of Tibetan Buddhism and as such has great prestige within Tibet. China's actions are designed to exert unquestioned state control over religion, to the point, in this case, of dictating whom Tibetans may revere as a religious hierarch. In other instances the state has assumed a visible presence in certifying certain incarnations and in harshly suppressing those who dissent. In the case of the Karmapa Lama, the head of the Karma Kagyupa sect of Tibetan Buddhism, the restrictions on his movement made it impossible for him to receive proper teachings from his traditional mentor; as a result he had no choice but to flee Tibet. He arrived in India at the beginning of this year. More recently, the Chinese government alone managed the search for another important incarnation within the Dalai Lama's sect, Reting Rinpoche. By all appearances, this is part of a continuing effort to control such searches in order ultimately to stage manage the discovery and enthronement of the next Dalai Lama. Human Rights Watch is concerned about the gross infringement of the right to freedom of conscience that this constitutes, all the more so because Chinese authorities have arrested people who have peacefully opposed this process. They include, most notably, Chadrel Rinpoche, a high-ranking lama from the Panchen Lama's monastery of Tashilhunpo: he is imprisoned along with several other Tibetans accused of working with the Dalai Lama from inside Tibet to identify the incarnation of the Panchen Lama. The issue here is not simply a question of polemics and intellectual disagreements, but of methods and tactics involving clear violations of human rights. As I have noted, the struggle over the recognition of the Panchen Lama led to a campaign of "patriotic education" that has imposed a harsh regimen of political tests on residents of Tibetan monasteries in order to root out any allegiance to the Dalai Lama. Again, this has not been simply a peaceful polemical issue: the campaign resulted in the expulsion of monks and nuns from their cloisters and the imprisonment and torture of some for refusing to accept state control of what they perceive as vital aspects of their religious lives and beliefs. The application of this campaign has not been uniform. Over the last year, it appears to have been winding down, but this may be because it is thought to have achieved sufficient success in subordinating Tibet's clergy to the political control of the state. On the other hand, recent and unusually harsh Chinese denunciations of the Dalai Lama and his followers may be a prelude to a renewed campaign. In any event, the campaign's effects remain, with many monks and nuns still barred from their cloisters and other, vocal dissidents still in prison. The campaign, widely implemented, has required clergy to demonstrate their rejection of the Dalai Lama and the child he has recognized as the Panchen Lama, as well as their acceptance of Tibet's status as an inalienable part of China. In the region that Tibetans know as Amdo, covering parts of the Chinese provinces of Qinghai and Sichuan, monks at Kirti and Rebgong monasteries have clashed sharply with the authorities, with resultant expulsions and arrests. This enforced subordination of religion to politics has brought about noticeable changes in the running of monasteries and nunneries: in some cases, the secular authorities have taken over their management; in others, monastic leaders have simply resigned themselves to accommodating the political directions of the state. In short, it is absolutely clear that unfettered religious practice does not prevail in Tibet's monasteries today. Torture and Abuse in Prison In addition to the fact that arrest and imprisonment in Tibet are frequently carried out as a result of peaceful dissident activity--in violation of international human rights law--there are serious abuses following detention. Incidents of severe beatings at the time of arrest, torture during incarceration, and severe beatings of inmates already sentenced have been reported with sufficient frequency and from a number of credible sources as to put the issue beyond doubt and, moreover, to demonstrate that these abuses are not isolated incidents but rather the product of a policy for dealing with political dissidents. Such reports continue to emerge. Human Rights Watch estimates that there are approximately 600 known political prisoners in Tibet, most of them monks and nuns. A Tibetan arrested in Lhasa in August 1999 for trying to raise the Tibetan flag in a public square, Tashi Tsering, was brutally beaten before being taken away by Public Security officers. In March 2000, he was reported to have committed suicide in prison a month earlier. In April 2000, a further death in custody was reported, that of Sonam Rinchen, a farmer from a town near Lhasa. He had been arrested with two others in 1992 for unfurling a Tibetan flag during a protest and was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Although information is difficult to obtain, a study by the Tibet Information Network suggests the incidence of deaths in detention in Lhasa's Drapchi prison among prisoners due for release in 1998-1999 averaged approximately 1 in 24. Several such deaths were reported as suicides. In one notable incident in May 1998, political prisoners in Drapchi staged major protests to coincide with a visit from a European Union delegation. The protests were non-violent, but the authorities' reaction was severe: one monk, Lobsang Gelek, died after he was shot. His family was later told that he had committed suicide. The authorities also attributed the deaths of several others prisoners who had demonstrated to suicide, despite credible reports that they had been beaten. Four nuns who had protested all died on the same day in the same way while held in strict solitary confinement. The authorities claimed they had committed suicide, but unofficial reports said they were singled out for particularly harsh treatment as suspected ringleaders of the protests. At least ten prisoners are believed to have died in the aftermath of the protests. Those subjected to beatings are reported to have included several nuns known to already have had their original sentences extended for continued non-violent protests in prison. Most prominent among them is Ngawang Sangdrol, one of several nuns who smuggled a recording of political protest songs out of prison in 1993, and whose sentence was increased to 18 years. To date, the Chinese government has been evasive in responding to European Union and NGO questions about the Drapchi protests, but it is clear that the imposition of arbitrary extensions to their sentences is a further abuse affecting Tibetan political prisoners. Only last week in fact, nine Tibetan prisoners in Kandze, an important town in the eastern reaches of the Tibetan Plateau, were reported to have had their five-year prison sentences for participating in a peaceful protest in October 1999, increased to ten-year terms. The Chinese authorities have also been unresponsive to concerns expressed by the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention about the cases of three Tibetans who had their sentences extended for staging a peaceful political protest during the Working Group's visit to Drapchi in October 1997. To date, Chinese authorities have refused to adequately explain their actions. Nor have they explained their failure to release Ngawang Choephel, the well-known Tibetan musicologist who was arrested while doing research in Tibet in 1995, and whose detention the Working Group has formally declared to be in contravention of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Human Rights Watch is also concerned about fifty Tibetan students detained late last month when they sought to return home via Nepal after previously leaving Tibet to further their education in India. They, too, may be victims of arbitrary detention. The Chinese government should release them immediately absent evidence that they have engaged in criminal acts. None should be held for peaceful political activity and all should be granted internationally recognized due process protections, including the right to be informed of the charges against them. The Individual Experience of Human Rights Violations One account included in the new Human Rights Watch publication, Tibet Since 1950: Silence, Prison, or Exile, tells the story of a young Tibetan student from the eastern reaches of the Tibetan Plateau, outside the boundaries of the Tibet Autonomous Region. (Such areas to the east of the TAR are composed of lower level Tibetan autonomous units. They are distinct from the regions that comprise the TAR but they are very much a part of the Tibetan world, in terms of history, culture, and nationalist identity and activity.) Although this young man's story does not exemplify the brutality of imprisonment experienced by many of those whose cases I have raised, it gives a broader picture of the reality of living under conditions in which respect for basic human rights is not a given. In the account, the student describes his struggle, in his region's minority institute, to have several courses taught in Tibetan rather than Chinese, and to have a Tibetan language publication reinstated to serve as an outlet for the creativity and intellectual activity of the institute's Tibetan students. The publication was reinstated, but was soon subjected to official censorship, which weighed more and more heavily on the student. Finally, when he himself authored a piece which alluded indirectly, but clearly, to the subordinate status of Tibetans, he was confined to the school compound and effectively barred from classes. In one stroke, he saw his future possibilities dashed; not for vocal protests for Tibetan independence, not for denouncing human rights violations, but simply for expressing discontent with the lot of Tibetans in China as he saw it. At that moment, he decided that his only alternative was to leave his family, friends, and the life he had known behind and flee into exile. That flight in itself was not without danger, but he made it over the border into Nepal and then into India. This student's story will serve, I hope, to demonstrate that human rights concerns in Tibet are important beyond the cases of those who engage in the most vocal forms of protest, or whose religious veneration of the Dalai Lama is under attack. Violations of human rights in Tibet resonate broadly into the everyday lives of Tibetans across the board. Recommendations Time and again since 1989, the U.S. government has voiced its intention to hold China accountable for its abysmal failings in safeguarding some of the most basic human rights of its citizens. The President and other senior administration officials have raised the issue of human rights violations in Tibet with President Jiang Zemin and other senior Chinese officials during summit meetings and other official gatherings. This is to be welcomed, but it has not resulted in meaningful, positive change. In fact, human rights conditions in China have noticeably deteriorated in the past year or more, something attested to in the State Department's most recent annual report. On the other hand, China is clearly sensitive to its international image and standing. That is why it has vigorously resisted any debate on its human rights record at the annual meetings of the U.N. Commission on Human Rights in Geneva. And under pressure, it has signed, although not always ratified, a number of important U.N. human rights treaties, including, most recently, the international covenants on civil and political rights, and on economic, social, and cultural rights. We recommend the following: 1) If Congress chooses to end the annual trade review and grant China PNTR, the existing review process must be replaced by a credible mechanism which can ensure that there is a continuing spotlight on China's human rights record. To this end, Human Rights Watch supports the formation of a standing, bipartisan human rights commission, as proposed by the House of Representatives in the bill it passed last month granting PNTR. We urge the Senate to join in enacting legislation to create such a commission, to include both Congressional and Executive branch members and a permanent staff, and to empower it to monitor human rights conditions in China and Tibet, including the state of religious freedom and worker rights, and to publish an annual report on its findings. The legislation establishing the commission should provide for some staff to be based in Beijing and Lhasa, as well as in the U.S., in order that effective, on-the-ground monitoring can be undertaken. In addition, the commission's annual report, including its findings and recommendations relating to U.S. policy and action, should be the subject of regular Congressional debate and vote, to take place before a designated date each year, after the report's delivery to the House and Senate. This will help ensure that human rights abuses in Tibet and China remain a key issue on the U.S.-China agenda. 2) The President, when he meets President Jiang Zemin, as at the expected summit meeting this fall during the APEC conference in Brunei, should speak out both publicly and privately, urging China's full compliance not only with its commitments to respect global trading rules but with its commitment to respect its international human rights obligations. Specific steps the U.S. should recommend to help improve human rights in Tibet include:

|