Can international human rights and humanitarian law survive when the major powers ignore it? That is the question posed by Russian forces’ widespread summary executions and indiscriminate bombardment of civilians in Ukraine.

In the case of Ukraine, at least, many governments seem determined to reinforce international standards. Forty-three countries so far have requested an International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation of the alleged perpetrators of these war crimes and possible crimes against humanity, which the ICC prosecutor has begun. The United Nations General Assembly and Human Rights Council have condemned the atrocities, and the council has opened a parallel inquiry. But we have not always seen such resolve in the global response to grave abuses by the most powerful nations.

The reaction to Russian atrocities in Ukraine stands in stark contrast to the lackluster response to the Chinese government’s repression in Xinjiang. There, aided by the world’s most intrusive surveillance system, Beijing has detained one million Uyghur and other Turkic Muslims to force them to abandon their religion, language, and culture. Human Rights Watch and others have concluded that these mass detentions and other systematic abuses amount to crimes against humanity. And that is just one aspect of the worst repression nationwide in China since the 1989 massacre of Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protesters.

There has been some international response to this repression. Groups of governments have repeatedly condemned the Chinese government’s abuses in Xinjiang – most recently, in a joint statement by 47 governments from all regions of the world including Germany. And the representatives of 50 UN special procedures – that is, independent experts rather than collective UN bodies – have issued parallel condemnations.

But the main United Nations institutions have been understated at best. Neither the UN Human Rights Council nor the UN General Assembly has held a debate, adopted a resolution, or started an investigation on Xinjiang. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres‘s cautiously worded statements of concern about Xinjiang have fallen far short of the seriousness of the persecution.

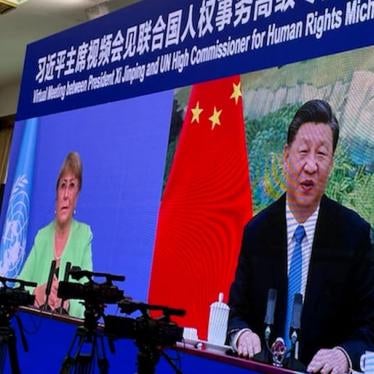

The UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, continues to withhold a long-promised report on Xinjiang that her staff has completed. Her spokesman said in December 2021 that it would be published within weeks. Instead, she agreed to visit China for what the Chinese government insisted would be a “friendly visit” and dialogue rather than the unfettered investigation in Xinjiang that she had rightly asked for.

The trip was a gift to Beijing. Bachelet held various quiet conversations with Chinese officials including Xi Jinping but exerted none of the public pressure that alone has a chance of forcing the Chinese government to ease its repression. She issued no forceful condemnation, praised other aspects of China’s human rights record, adopted Beijing’s false “counterterrorism” narrative, and despite contrary evidence, accepted without question Beijing’s claim that the detention centers were now closed. She trumpeted a new dialogue with the Chinese government, but it has long been Beijing’s strategy to substitute such quiet backroom conversation for any public criticism.

The US government has barred all imports from Xinjiang as presumptively tainted by Uyghur forced labor unless the importer can prove otherwise (which given the opacity of supply chains in Xinjiang is virtually impossible). But the European Union has yet to follow suit. The United States, Britain, Canada, and the European Union have imposed targeted sanctions regarding the repression in Xinjiang. But European Union leaders, with former German Chancellor Angela Merkel in the EU presidency, tried to push through an investment agreement with China without demanding an end to the forced labor. It took the European Parliament to quash that idea.

The problem isn’t only China. The US government also has been reluctant to hold itself to international human rights standards. When the ICC seemed posed to investigate US torture in Afghanistan, the administration of Donald Trump outrageously imposed sanctions on its prosecutor at the time. The ostensible reason was that, while Afghanistan had joined the ICC treaty, the United States had not, even though the treaty confers jurisdiction over crimes such as torture committed by anyone on the territory of a member country.

President Joe Biden has since lifted those sanctions. In the case of Ukraine, which has granted the ICC jurisdiction over crimes on its territory, Biden has endorsed and said the US government would cooperate with the ICC investigation of potential war crimes by Russian forces, even though Russia has also not joined the ICC.

It remains to be seen how the US government will react to any potential future ICC investigation of US personnel in a country where the ICC also has territorial jurisdiction. Both Democratic and Republican members of Congress are now endorsing the ICC investigation in Ukraine, laying bare the hypocrisy of the past US position. The US shift was undoubtedly facilitated by the ICC prosecutor’s announcement that, as he continues his Afghanistan investigation, he intends to de-prioritize for the time being his inquiry into alleged US crimes.

More imminently, the US position will be tested by the ICC investigation of Israeli war crimes such as its illegal settlements in Palestine, given that Israel has never joined the court, although Palestine has.

Yet the good news is that, even without the major powers, a broad array of governments has repeatedly supported and even advanced international rights standards. The ICC is the product of a large coalition, even though the United States, Russia, and China never joined. These major powers were similarly absent as the rest of the world banned anti-personnel landmines and cluster munitions. Yet, today, the ICC enjoys international credibility, and the norms against landmines and cluster munitions, both indiscriminate weapons that endanger civilians, remain strong.

In short, it may be in the nature of major powers to seek to exercise their power unconstrained by the enforcement of international law, but strong global support for those standards, and the institutions to enforce them, can generate intense pressure to comply regardless of major-power proclivities.

Yet we should not be complacent at the strong international response to Russian outrages in Ukraine. Russia is a significant military force — though apparently a less impressive one than most people thought before its invasion of Ukraine. But the Kremlin has relatively little economic influence. China is another matter.

The Chinese government is an economic powerhouse that has shown no reluctance to use its clout to oppose scrutiny of its conduct and to undermine the international human rights system. When the Australian government proposed an independent investigation into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic, Beijing responded with punitive tariffs. It earlier had retaliated against Norway when the Oslo-based Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize to the imprisoned Chinese pro-democracy campaigner Liu Xiaobo, even though the Norwegian government has nothing to do with the decisions of the private Nobel Committee. And the Chinese government threatened to withhold Covid-19 vaccines from Ukraine until it removed its name from a joint statement criticizing Beijing’s repression in Xinjiang – a blackmail tactic that UN diplomats told Human Rights Watch the Chinese delegation has used to scare other countries into silence as well.

Similarly, Chinese President Xi Jinping has used the trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, ostensibly an infrastructure development program, to purchase support for his anti-rights positions at the United Nations. The lack of transparency for Belt and Road loans, like financing from other Chinese institutions, make them ideal vehicles for Beijing to buy the outcomes that it wants.

Beyond trying to silence critics of its repression and to undermine broader enforcement of human rights standards, the Chinese government is trying to weaken the standards themselves. In its view, human rights should never be enforced by pressure, just by “win, win” (for the abusers, not the victims) polite conversation.

If Beijing had its way, human rights would be reduced to a measurement of growth in gross domestic product. It would brush aside economic and social rights, which require examining how the worst-off segments of society are treated, as well as civil and political rights, which are needed to ensure that a government remains accountable to its people.

Russian atrocities in Ukraine are appalling, but given the world’s reaction to them, they do not pose a threat to global standards. Indeed, they may even end up consolidating support for those standards. Rather, the real threat to rights comes from Beijing, which appears determined to undermine those standards altogether. So far, the world’s response has been inadequate. The economic cost of standing up to the Chinese government is real, but it is a cost worth bearing, because the very foundation of the international human rights system built over the past 75 years is at stake.