In late November, a senior local Chinese Communist Party official toured three townships in Sog, a county in the Tibet Autonomous Region that has a history of resistance to state controls on religion. His goal: to ensure local Tibetan officials endorse government policies on the recognition of Tibetan Buddhist incarnations.

Attendees at these sessions included “over 120 township officials, staff of monastery management committees, village-based cadres, village officials, local police, [and] schoolteachers,” according to state media. Participants “unanimously declared their willingness to follow laws and regulations concerning Tibetan Buddhist incarnation affairs.”

Since 2007, Chinese authorities have imposed regulations limiting the recognition of reincarnate lamas, which include most of the religious leaders in Tibetan Buddhism. These provisions specify that reincarnations may not be recognized without state approval and must be born within China’s borders. High-ranking incarnations must be selected using the “Golden Urn,” an 18th century Chinese lottery system that had scarcely been used by Tibetans until 2007, when the party mandated it as the only legal way to select top-ranking lamas.

These regulations – imposed by a political party that denounces religion as delusion and implemented by a government that, in Tibet, bans its employees from religious practice – are widely understood as preparation for what officials call the “post-Dalai era.” They are the legal groundwork for the Party’s plan to capitalize on the future death of the current Dalai Lama, who is 86 and in exile, by appointing their choice as the next one.

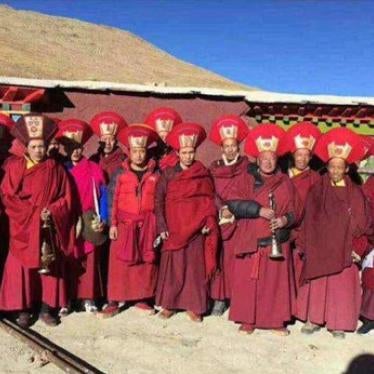

In recent years, Chinese officials have announced meetings where selected senior monks are required to “study” these policies and promise their support. Since 2018, all monastics, particularly those with teaching or official duties, have been required to meet “Four Standards,” including “political reliability” and “being dependable at critical moments.” Both are believed to involve support for the Chinese government’s choice of the next Dalai Lama and any other reincarnate lama.

Recent local meetings such as those in Sog county show these demands are now being enforced more widely. Given the state-of-the-art preventive policing that China uses to “maintain stability” in Tibet, there is no question of monastic and lay believers being able to express their real views about authorities’ choice of Tibetan religious leaders.