(Nairobi) – Burundi authorities and ruling party members have used fear and repression against the political opposition and the last remaining independent organizations and media ahead of the country’s general elections. Widespread impunity for local authorities, security forces, and members of the ruling party’s youth league, the Imbonerakure, prevail, as campaigning opens on April 27, 2020 for the elections scheduled to begin on May 20.

The election will take place following confirmation on March 31 of the country’s first Covid-19 cases. The president’s spokesperson said on April 7, in reference to the pandemic, that elections will go ahead because “[Burundians] are a people blessed by God.” Health authorities have blocked journalists from accessing a Covid-19 press conference, which could indicate government attempts to suppress information about the pandemic.

“Violence and repression have been the hallmark of politics in Burundi since 2015, and as elections approach and the Covid-19 pandemic unfolds, tensions are rising,” said Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “There is little doubt that these elections will be accompanied by more abuses, as Burundian officials and members of the Imbonerakure are using violence with near-total impunity to allow the ruling party to entrench its hold on power.”

Human Rights Watch conducted phone interviews between November 2019 and April 2020 with more than 25 people, including victims, witnesses, members of civil society groups, police, and ruling party sources, who described abuses in 6 of Burundi’s 18 provinces. Human Rights Watch also documented killings, disappearances, arbitrary arrests, and threats and harassment against real or perceived political opponents over the last six months.

Reports from media and human rights defenders confirmed the abuses. Several human rights observers told Human Rights Watch that these kinds of abuses are not limited to these six provinces. Between January and March, Ligue Iteka, an exiled Burundian human rights organization, documented 67 killings, including 14 extrajudicial executions, 6 disappearances, 15 cases of gender-based violence, 23 cases of torture, and 204 arbitrary arrests. Although to a much lesser extent, violence against ruling party members and youths – including killings – has also been reported.

Since President Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision to run for a controversial third term triggered a serious human rights crisis five years ago, confirming details of abuse has become increasingly difficult, as fear has engulfed the country and the authorities have intensified efforts to silence the media and activists, Human Rights Watch said.

On April 11, two Health Ministry officials blocked four journalists from attending a Covid-19 news conference in Bujumbura. “They told us we are enemies of the nation, and that we are not allowed to go in,” one journalist told Human Rights Watch. He said officials told them that only Radio Télévision Nationale du Burundi (RTNB), Rema FM, and Mashariki TV – all close to the ruling party – were allowed to enter. According to the Burundian Union of Journalists, on April 9, a journalist from Radio Isanganiro and his driver were “abused” by some Imbonerakure members, who deflated the tires of their vehicle, while he was investigating an attack on an opposition member.

A human rights observer told Human Rights Watch on April 2 that he had been forced into hiding after investigating the killing of a representative of the opposition National Congress for Freedom (Congrès national pour la liberté, CNL), on March 16 in Bujumbura Rural province. “Ruling party members accused me of sharing the information with exiled human rights defenders and got the [provincial] prosecutor to issue multiple summons ... so I’ve had to go into hiding,” he said. He was informed on April 8 that an arrest warrant had been issued against him.

In Nyamurenza commune, Ngozi province, a man said he was beaten by a group of Imbonerakure members armed with bats and clubs the evening of February 9, when he tried to intervene as they harassed his neighbor. “I screamed, fell down, and felt blood oozing out of my head,” he said. “I thought I was going to die.... They wouldn’t give me water.... I heard them say: ‘Don’t take him to hospital; let him die.’”

His neighbors eventually convinced the youths to let them take him to a hospital, but when the victim and his wife tried to file a complaint against the local Imbonerakure chief the next day, the police commissioner instead arrested his wife and several other witnesses.

Human Rights Watch, local media, and other rights organizations have documented the appearance of dead bodies in various parts of the country, generally showing signs of violence, and buried by local officials and Imbonerakure members before they are identified.

On November 15, Marie-Claire Niyongere, the deputy leader of the women’s wing of the CNL in Kiganda commune, Muramvya province, was found dead in a forest with injuries to her neck and genitals, media reported. A local administrator said she was sexually assaulted before being killed.

Little information has been released about several major security incidents in recent months. Between February 19 and 23, reports of skirmishes between security forces and alleged “criminals” in western Bujumbura Rural province emerged as photos and videos circulated online showing detained people and dead bodies surrounded by police and local residents. Police said 22 “armed criminals” were killed and 6 others arrested, and 2 policemen were killed, but several investigations suggest that many of the victims were killed after capture. On February 22, a police source warned Human Rights Watch that Imbonerakure members and demobilized soldiers from other parts of the country were simulating an attack to set the stage for a crackdown and justify a subsequent wave of arrests of CNL members.

The conviction on January 30 after a flawed trial of four Iwacu journalists who were arrested while going to report on fighting between security forces and the rebel group RED-Tabara in October 2019 underscores the dangers of investigating security incidents, Human Rights Watch said.

In addition to threatening public statements by senior government officials, the restrictive 2018 press law and a new code of conduct for journalists during elections have further constrained the media’s ability to publish information of public interest.

Although the East African Community will send an election observation mission, the government has still not signed a working agreement with the African Union-mandated human rights observers. In recent years, the government has attempted to shield itself from international scrutiny by blocking independent monitors, denying access to the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Burundi, and shutting down the UN Human Rights Office in Burundi.

The Burundian authorities should immediately and publicly order officials and Imbonerakure members to stop intimidating, beating, illegally detaining, and ill-treating people. They should investigate and prosecute the crimes documented and restore conditions for free and fair elections, which includes ensuring that the media and civil society can work freely, Human Rights Watch said. Anyone unlawfully detained, including human rights defenders and journalists, should be immediately and unconditionally released. Tensions may be exacerbated by the pandemic, and accurate information about measures to contain the virus should be provided.

On April 10, 2020, Human Rights Watch sent its key recent findings to the minister for external relations and international cooperation, with the ministers for the interior and patriotic formation, justice, human rights, social affairs and gender, and public security in copy, but received no response.

“Government officials, through their actions and their statements, are sending a clear message to the media ahead of the elections that human rights abuses must be hidden, not exposed,” Mudge said. “Burundi’s donors and partners should take a strong public stance against the government’s measures to clamp down on free expression and quash dissent. The UN and others should make clear that there will be consequences for those responsible for abuses, including through targeted sanctions.”

Five Years of Repression

Burundi has descended into lawlessness since April 2015, after President Pierre Nkurunziza announced his bid for a disputed third term, despite the two-term limit in the Arusha Accords. The political framework, signed in 2000, was the first of several power-sharing agreements intended to end Burundi’s civil war.

A UN Commission of Inquiry concluded in September 2017 that it had “reasonable grounds to believe that crimes against humanity have been committed and continue[d] to be committed in Burundi since April 2015.” In a September 2019 report, the commission applied the UN Office for the Prevention of Genocide and the Responsibility to Protect’s Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes and found that the eight common risk factors for criminal atrocities were present in Burundi. The International Criminal Court opened its own investigation in 2017, a year after Burundi announced it was leaving the court.

Since 2015, members of the Imbonerakure have become increasingly powerful in many parts of the country, killing, torturing, arresting, beating, and attacking real and suspected government opponents, often working with police, local authorities, and security services.

A May 2018 constitutional referendum took place against a backdrop of widespread abuses by local authorities, the police, and Imbonerakure members. The constitutional changes extended the presidential term to seven years, reset the clock on terms served, dismantled the ethnic power-sharing arrangements that were central to the Arusha Accords, and gave more power to the president.

The referendum’s aftermath was marred by abuses against people suspected of voting against or encouraging others to vote against the referendum. In its December 2015 report, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ fact-finding mission to Burundi concluded that acts contrary to the Arusha Accords, if carried out without a transparent, inclusive, and consultative process, could “derail the peace of the country.”

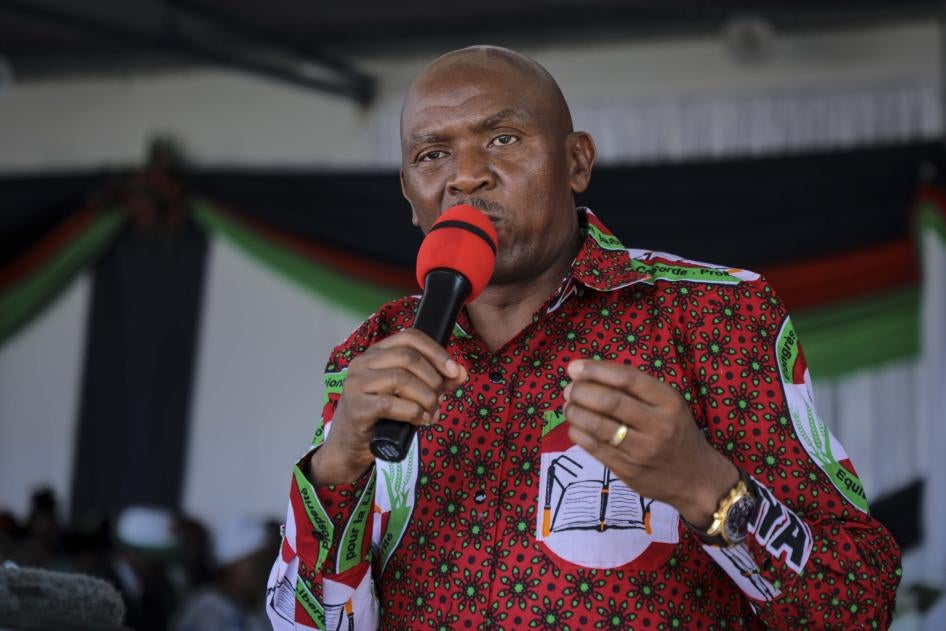

Since February 2019, when Agathon Rwasa, an opposition leader, registered his new party, the CNL, local administrators and Imbonerakure members have committed widespread abuses against its members, with authorities mostly looking the other way. The CNL was formerly known as the National Liberation Forces (Forces nationales de libération, FNL), an armed group, but it became a political party in 2009. Rwasa ran as head of a coalition in the 2015 presidential elections and registered the CNL after changes to the constitution prevented him from running in 2020 as an independent.

On January 26, the ruling National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil national pour la défense de la démocratie-Forces de défense de la démocratie, CNDD-FDD) nominated Évariste Ndayishimiye, the party’s secretary-general, as its presidential candidate. Days earlier, Parliament adopted a law granting exorbitant privileges to President Nkurunziza, including a one-off US$500,000 payment, a luxury villa, six cars, and a lifelong allowance after he steps down. A law was adopted in March giving him the official status of “Supreme Guide of Patriotism.”

In December 2019, Human Rights Watch documented that local officials and Imbonerakure members had extorted “donations” to fund the 2020 elections, in many cases with threats or force, and had blocked access to basic public services for those who could not show proof of payment, in the midst of a dire humanitarian crisis.

Since 2015, hundreds of thousands of Burundians have fled the country and, according to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), by February 2020, there were over 335,000 Burundian refugees in neighboring countries. Between September 2017 and April 2020, 80,000 refugees had returned to Burundi under a voluntary repatriation program supported by the UN refugee agency. These repatriations are continuing despite the pandemic.

Violence, Fear, and Intimidation

Local administrative officials and Imbonerakure members have entrenched their control over the population as elections approach. One Imbonerakure member told Human Rights Watch that local leaders of the youth league give financial rewards to those who kill, arrest, or beat members of the CNL. According to reports, some Imbonerakure members operate within the framework of the Mixed Security Committees (Comités mixtes de sécurité, CMS), established to provide assistance to the population and security institutions.

Although the cases Human Rights Watch documented are most likely only a small fraction of the abuse taking place in Burundi, they illustrate how tensions continue to rise in a context of violence, fear, and intimidation created by ruling party youths, police, and local officials acting with impunity.

Over 80 members of the CNL have been arrested in Ngozi province since October 2019, based on interviews with CNL representatives, witnesses, and family members, and local media reports. The reported killing of an Imbonerakure member, who was found dead in Busiga commune on October 5, and skirmishes between Imbonerakure and CNL members in early November in Marangara and Nyamurenza communes appear to have triggered the arrests.

The vast majority of those arrested were transferred to Ngozi Central Prison, where many have been on trial on attempted murder, assault, and property destruction charges. According to sources involved in the cases, 4 were released, 41 members of several communes across the province have been convicted and are appealing the verdicts, and over a dozen are currently detained in the jails in their local communes.

On November 7, Evariste Nyabenda, a member of the CNL, died – reportedly of his injuries – after being beaten weeks earlier by Imbonerakure members during a public meeting in Burenza, Marangara commune. Several neighbors told Human Rights Watch that the Imbonerakure attacked Nyabenda after he defended someone who had commented during a local meeting that there was no peace in Burundi. Nyabenda was detained after the beating, and later taken to Kiremba hospital, where he reportedly died of internal injuries.

During his wake, on November 11, witnesses said, Imbonerakure members danced in front of the victim’s house. One witness said they sang in Kirundi: “We have to force them to understand, but they are deaf and they don’t understand anything.”

That evening, Imbonerakure members threw stones at Nyabenda’s house and at least one other house in the locality, damaging them. His widow and two children have gone into hiding. A neighbor told Human Rights Watch “[The next day,] two policemen came to my house, asking for my husband. Five Imbonerakure had encircled our house. They threatened us and told us go to Rwanda, that the CNDD-FDD doesn’t want opponents in the country.” Several sources within the CNL and from the area said that 17 members were arrested in the following days and taken to Ngozi Central Prison. They are on trial on charges including attempted murder, assault, and property destruction.

Since January 2020, Human Rights Watch has received over a dozen credible reports of disappearances in Cibitoke and Bubanza provinces. On March 24, Fabien Banciryanino, a local member of parliament, wrote a letter to the Bubanza general prosecutor requesting an investigation into 21 cases of disappearances and killings in his province since 2016.

Machete attacks by Imbonerakure members or unknown assailants have recently been reported in several parts of the country by exiled rights organizations and local media. On January 5, an opposition member in Kirundo commune and province was attacked and cut with a machete as he returned home in the evening. He said that he was cut 11 times and spent 2 weeks in hospital following the attack, but that the authorities refused to investigate.

On November 20, 2019, local Imbonerakure members painted red crosses on more than 100 houses of CNL members in Busiga commune, Ngozi province. One local resident told Human Rights Watch “Around 1:15 a.m. we saw a group of around 15 Imbonerakure come to the village and paint our houses with red crosses. We shouted at them and eventually they left, but not before painting my front door.”

A CNL representative said that at least 180 houses of CNL members had been targeted in the area. These acts of intimidation carry particular significance in the Great Lakes region – houses were marked with the word “Tutsi” during the 1994 Rwanda genocide. Other acts of intimidation toward suspected political opponents reported to Human Rights Watch include destroying crops and killing cattle.

Muzzling of Independent Groups, Media

Prosecutions, threats, and intimidation since 2015 have forced many Burundian activists and journalists to stop working on sensitive political or human rights issues or to leave the country. Several human rights defenders and journalists are in prison, convicted of security-related charges. The last remaining independent rights organization, PARCEM, was suspended in June 2019 for “tarnishing the image of the country and its leaders.”

Mounting Pressure on International Organizations

International organizations operate in a heavily restricted environment and regularly face government attempts to control the narrative on everything from health and food security to human rights and politics, and to interfere with and curtail their activities through bureaucratic obstacles.

On October 1, 2018, the authorities suspended the activities of foreign nongovernmental groups for three months to force them to reregister, including by submitting new documentation stating the ethnicity of their Burundian employees. The move stems from a 2017 law on foreign nongovernmental groups requiring them to adhere to ethnic quotas first introduced for state institutions and the army in the Arusha Accord. Many organizations fear the information will put their staff at risk of ethnic targeting.

By March 2019, about 93 out of an estimated 130 international groups were reregistered, although it is unclear to what extent they complied with the requirements. Some refused to comply and left the country. A commission was created to play an oversight role in recruiting national staff of foreign groups and to monitor compliance with the ethnic quotas. On February 13, a letter from Interior Minister Pascal Barandagiye again requested international groups to provide detailed personal information about all employees, including, in the case of Burundians, their ethnicity.

In the context of Covid-19, Human Rights Watch has documented that the authorities have failed to ensure adequate food, health care, hygiene, and sanitation in some quarantine locations and blocked aid organizations from entering and providing assistance to people in quarantine.

Clampdown on Media Freedom

With the approaching elections, the government has stepped up efforts to intimidate or suspend remaining independent media. Since March 2019, the Voice of America (VOA) and the BBC have been blocked from working in Burundi, and journalists are banned from “providing information directly or indirectly that could be broadcast” by either the BBC or VOA.

The 2018 amended press law and a new “Code of Conduct for Media and Journalists in the Election Period for 2020” require journalists to only provide information considered “balanced” or face criminal prosecution, and forbids them from publishing information about the elections or results that do not come from the national electoral commission. Based on media reports, all media representatives signed the code of conduct on the spot when it was presented at a meeting in October 2019 by the National Communications Council (CNC) president, who said that all media would be held to it.

Iwacu, the last remaining independent newspaper in Burundi, has borne the brunt of the government’s ire, with a flawed trial and conviction of Christine Kamikazi, Agnès Ndirubusa, Egide Harerimana, and Térence Mpozenzi, journalists at the newspaper. The UN special rapporteurs on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression and on the situation of human rights defenders, and the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention condemned the prosecution of the journalists, who remain in jail.

An Iwacu statement on March 29 said that Anglebert Ngendabanka, a lawmaker, had threatened to “crush the head” of one of its journalists after the newspaper published an article implicating him in recent attacks against members of the CNL in Cendajuru commune, Cankuzo province.