(Istanbul) – What 15-year-old Rawan, a Syrian refugee living in Istanbul, wants most is simply to be back in school. In Syria, she’d been a good student with hopes of attending university, but now her future looks bleak. “It’s like we put our dreams in balloons and just let them all fly away. We can’t make any of them stay and come true,” she says, distraught at the continued absence of a school, classmates and teachers in her daily life.

When we met Rawan in April, bureaucratic delays in her family’s registration with the Turkish government had left her unable to enroll in a local public school. Her parents couldn’t afford the modest fees for private “temporary education centers” accredited by the Turkish government for Syrian refugees to supplement the public schools. So she was stuck.

The solution will require global cooperation.

In theory, the United Nations General Assembly summit on refugees and migrants on September 19–20 offers a unique opportunity for countries around the world to address the refugee education crisis together. The summit is meant to be “a historic opportunity to come up with a blueprint for a better international response” to large refugee and migrant movements. The U.N.secretary-general Ban Ki-moon even called on member states back in March to draft a “global compact on responsibility-sharing” that would outline a comprehensive plan for more equitable cooperation in protecting and assisting refugees. But initial attempts to draft such a compact in time for the summit stalled and were ultimately scrapped. Now the compact isn’t scheduled to come out until 2018.

A more concrete opportunity for global responsibility-sharing will take place the day after the UNGA summit, during the White House-organized Leaders’ Summit on Refugees. The gathering will explicitly aim to put 1 million more refugee children in school. It will also seek to grant 1 million refugees access to lawful work. In fact, achieving the latter goal will be crucial to achieving the former.

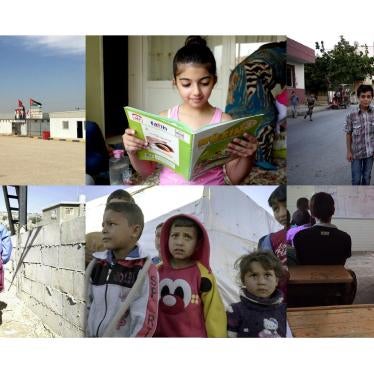

As Human Rights Watch has documented in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, access to education and lawful employment are inextricably linked. When adult refugees can’t legally work, they struggle to provide for their families. As a result, they can’t afford basic school-related costs, or they end up asking their children to abandon their education and go to work to help put food on the table. It’s a challenge Rawan’s family knows well: Without work permits, her parents have struggled to find decently paid jobs, and her 12-year-old brother works in a garment factory to help with the bills.

Until host countries undertake policy reforms that grant adult refugees access to the formal labor market, the problem will persist. But they need support to make these bold policy changes. It is in the interest of Turkey and other front-line countries to improve refugees’ access to lawful work, since that would reduce dependence on humanitarian aid, ease poverty and give more children the chance to attend school regularly. But the politics of allowing refugees to work, especially in countries with significant unemployment rates, are tricky.

The other two goals of the Leaders’ Summit will play a key role in navigating this challenge. The gathering aims to increase humanitarian funding and refugee resettlement commitments. This is important, because countries such as Turkey have largely been left to contend with protecting refugees on their own. Turkey has registered more than 2.7 million Syrian refugees and reportedly spent $10 billion on its efforts to host them. In comparison, the world’s wealthier countries have pledged only 185,000 resettlement places for Syrians, and the historically generous pledges made at the London Donor Conference in February resulted in an allocation of only $741 million for Turkey this year. Other countries can and should do more to alleviate the pressure on countries like Turkey and create a climate that is conducive to positive policy shifts.

Being in school gives children the opportunity to learn crucial skills and build a strong foundation for their future livelihoods and careers. It protects them from exploitation, helps them integrate and equips them to rebuild their communities when the time comes. We need to act now to ensure that this generation of refugee children is not forced to grow up without an education.

This is exactly why “responsibility-sharing” must become more than a buzzword at the summit. It needs to be a genuine commitment that results in tangible, decisive, concerted, international action. If wealthier countries leave front-line countries to face this challenge alone, we all risk denying vulnerable children such as Rawan their dreams of an education and the chance of a better future.