With the holiday season fast approaching, many people will be shopping for jewellery gifts. This is a good moment to ask whether the necklaces, rings, and earrings that will be given to loved ones this festive season have been produced responsibly.

A new standard has just been introduced for companies in the jewellery supply chain with rules on labour rights, indigenous people's rights, the environment, and how to ensure that materials used aren't produced under abusive conditions. The standard has been produced by the London-based Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), an organisation which brings together key players from the gold, platinum, and diamond industries. Adhering to the Code of Practices will be a requirement for the more than 300 member companies, including some of the largest mining companies and refiners in the world: De Beers, Rio Tinto, and AngloGold Ashanti to name a few.

Yet the Code of Practices is not the "gold standard" that it should be. In particular, it does not have clear requirements for ending abusive conditions in the full supply chain, or for adhering strictly to international laws and norms for resettlement and indigenous peoples' rights.

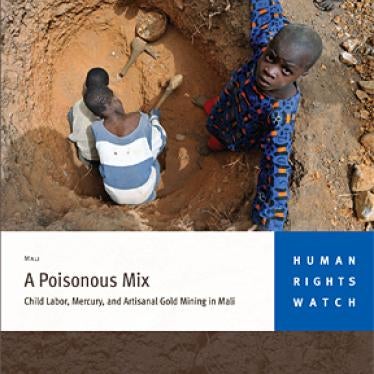

Companies bear responsibility for their impact on human rights throughout the whole supply chain, including for small-scale mining. The new standard fails to explicitly acknowledge this vital element of due diligence. Most minerals from small-scale mines go through the hands of several buyers before reaching the global market, and RJC member companies may be trading in minerals that come by an indirect route from these mines.

In particular, the code doesn't require companies to look beyond their immediate suppliers to find out where they got the gold or other materials. And indirect sourcing is all too common. A local trader at a mine in southern Mali told me, for example, that he bought gold from adult and child labourers, and then sold it to a wealthy exporter in the city, who then exported the gold to companies in Switzerland and Dubai.

The standard falls short, too, when it comes to the human rights impact of large-scale mining companies on local communities. It acknowledges that mining companies may cause involuntary resettlement of communities. But it doesn't spell out how to carry out resettlement in a way that respects the rights of the people being forced to move.

Such detail is often vital, as Human Rights Watch research on the plight of local residents resettled by Vale and Rio Tinto for coal mining in Mozambique illustrated. There, largely self-sufficient farmers were resettled to arid land far from rivers and markets, resulting in hunger and, later, dependence on mining companies for food assistance.

When new mining facilities affect the lives of indigenous people, the standard requires companies to "work to obtain" their free, prior and informed consent during the planning and approval stages. This language is vague and subverts the gains made by indigenous rights activists-notably during negotiations for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples-in achieving a full requirement to "obtain" such consent.

In recent years, the precious metals industry has been keen to show its commitment to ethical business, notably through creating voluntary standards. The new standard is one of several international initiatives for responsible sourcing of precious metals. Most efforts have sought to create supply chains that are free of conflict minerals - that is, minerals that help finance armed groups in war.

But the RJC has managed to broaden the focus significantly, to include child labour, social, and environmental concerns. For example, it clearly prohibits the use of child labour and sets out detailed measures for "remediation" that companies have to take when they do find child workers in their facilities. It also-at long last-forbids the practice of dumping mining waste into rivers. Most important, the code strengthens the notion that companies are accountable for the human rights and environmental impact of their actions. This is a hugely important message.

Yet, to truly make the precious metals supply chain responsible, a next step is needed: binding regulation. History's long and growing catalogue of corporate human rights disasters shows how badly companies can go astray without proper regulation. Voluntary initiatives like this one help define good human rights practices for companies, but only enforceable rules will ensure real, systematic change in the precious metals industry.