“What is a House without Food?”

Mozambique’s Coal Mining Boom and Resettlements

Map 1: Tete Province, Mozambique

Map 2: Sites of Original and Resettled Villages in Tete Province

Summary

I used to grow sorghum, enough to fill the storehouse, probably about five or six sacks. We had a full kitchen of maize. We used to buy food when there was a problem, but usually we didn’t have to.

The farming land we received [upon resettlement] is red, not black like we had before. I tried to grow maize and it died. Sorghum also failed.

The new house is just a house. I am not that satisfied. What I can say is, what is a house without food? I cannot eat my house.

—Maria C., resettled farmer, Mwaladzi, Rio Tinto resettlement village, October 5, 2012

A surge of foreign investment in Mozambique’s vast natural resources, including large reserves of coal and offshore natural gas, promises new economic possibilities for a country long ranked one of the poorest in the world. Multinational mining and gas companies have invested billions of dollars in Mozambique in the past ten years and the government estimates it will attract an additional fifty billion dollars of investment in the coming decade. But without adequate safeguards, the explosive growth of the mining sector could lead to human rights violations and squander an opportunity to reduce widespread poverty.

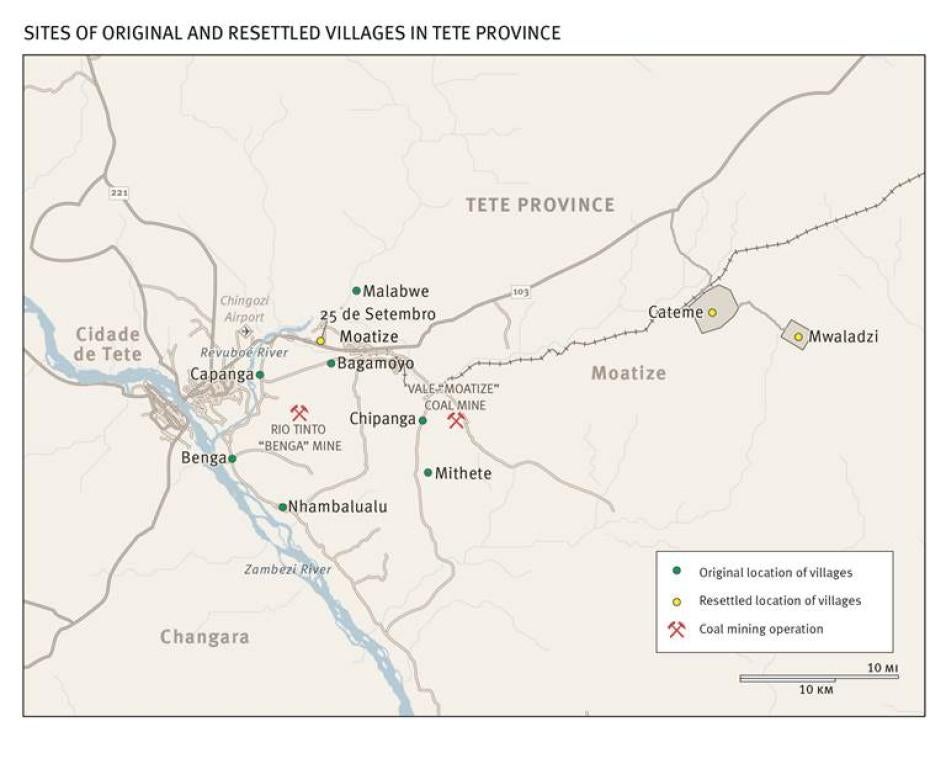

In coal-rich Tete province, local communities displaced and resettled from 2009 to 2011 due to coal operations owned by mining companies Vale and Rio Tinto have faced significant and sustained disruptions in accessing food, water, and work. Many farming households previously lived along a river, could walk to markets in the district capital Moatize, and say they were self-sufficient. They are now living in sites roughly 40km away with agricultural land of deeply uneven quality, unreliable access to water, and diminished access to key sources of non-farming income. Many resettled households have experienced periods of food insecurity, or when available, dependence on food assistance financed by the companies that resettled them.

Serious shortcomings in government policy and oversight and in private companies’ implementation led to the relocation of communities to these sites. There has also been insufficient communication between the government and the mining companies with resettled communities, as well as a lack of accessible and responsive mechanisms for participation in decision-making, expression of complaints, and redress of grievances. Frustrated by the lack of response to their situation, an estimated 500 residents from the Vale resettlement village Cateme protested on January 10, 2012, blocking the railroad linking Vale’s coal mine with the port in Beira. This demonstration, and a violent response by local police—who beat several protestors—brought national scrutiny to the problems in Cateme and the other resettlements.

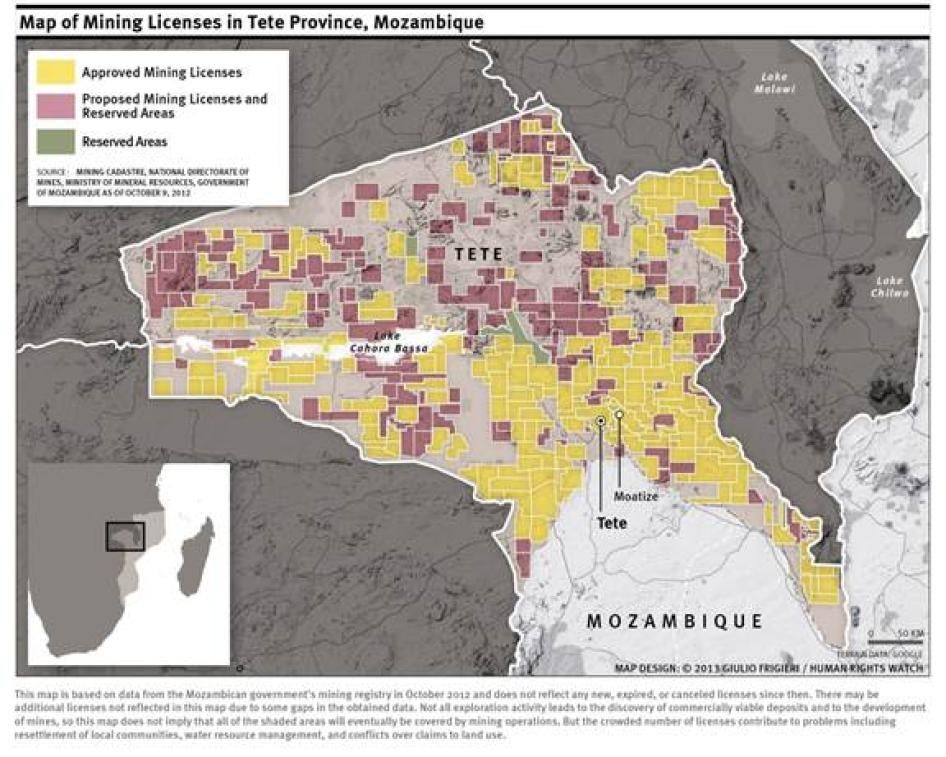

Tete province in central Mozambique is home to an estimated 23 billion tons of coal reserves, attracting investors from across the globe. The Mozambican government’s speed in approving new mega-projects has outstripped its development and implementation of adequate safeguards to protect the rights of affected populations. Despite the resettlement of local communities to make way for coal mines as early as 2009, the government had no specific regulations on resettlement until August 2012.

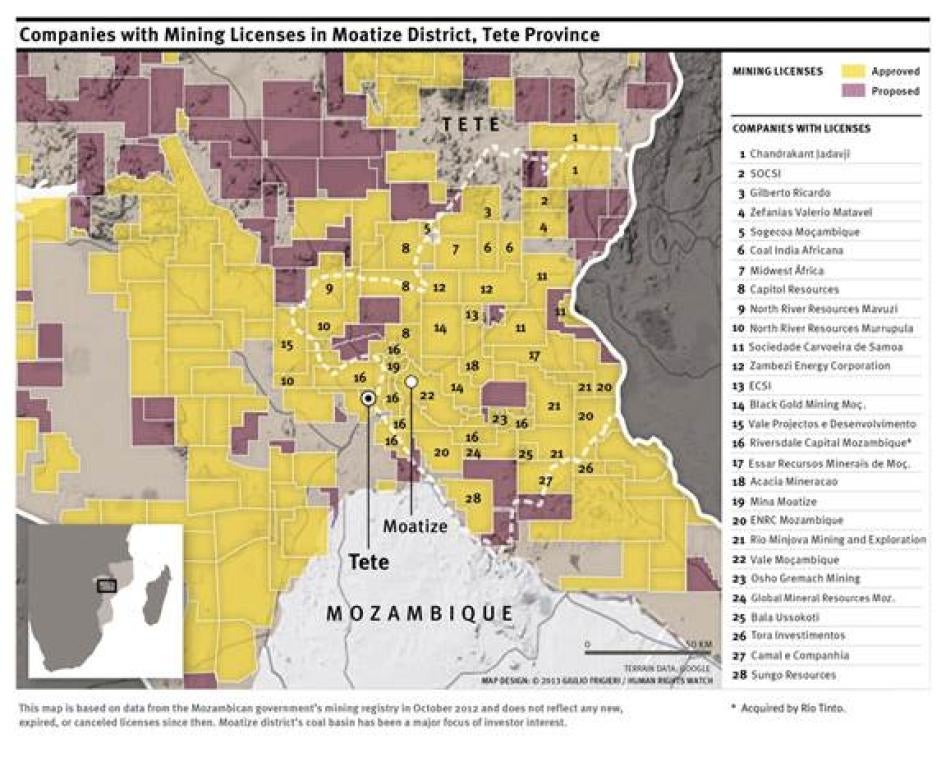

According to data from the Mozambican government’s mining registry in October 2012, the government has approved at least 245 mining concessions and exploration licenses in Tete province, covering approximately 3.4 million hectares or 34 percent of its area. Coal mining accounts for roughly one-third of these. When factoring in all applications pending approval, the amount of land involved jumps to roughly 6 million hectares, or approximately 60 percent of Tete province’s area. There has been little management and planning for the cumulative impact of numerous mining projects. And while not all exploration activity will lead to the development of mining projects, the high concentration of land designated for mining licenses in Tete province has profoundly limited the availability of appropriate resettlement sites for communities displaced by mining operations.

Map 3: Mining Licenses in Tete Province

The earliest to begin coal mining operations include two of the world’s three largest mining companies: Vale, a Brazilian firm, and Rio Tinto, an Anglo-Australian firm that acquired the Australian company Riversdale and its holdings in Tete province in 2011. Jindal Steel and Power Limited, an Indian company, and Beacon Hill Resources, a British firm, also started mining coal in 2012. Several other companies and partnerships are still in prospecting or development phases.

Vale and Rio Tinto’s development of open-pit coal mines, access roads, and related infrastructure has displaced thousands of people from local communities, primarily subsistence farmers. Between 2009 and 2010, Vale resettled 1,365 households to a newly-constructed village, Cateme, and an urban neighborhood, 25 de Setembro. Rio Tinto and Riversdale resettled 84 households to a newly-constructed village, Mwaladzi, in 2011. Rio Tinto plans to resettle an additional 595 households to Mwaladzi by May 2013 and to urban areas near the district capital Moatize. Jindal Steel and Power Limited is planning to resettle 484 families once the government approves its relocation site and plans. It will compensate more than a thousand other households for losing farmland or other assets.

Through interviews with 79 resettled or soon-to-be-resettled community members and 50 government officials, company representatives, civil society activists, and international donors, Human Rights Watch investigated the human rights impacts of the resettlements and the response of the Mozambican government, Vale, and Rio Tinto. Our research shows the resettlements, particularly the provision of poor-quality agricultural land and unreliable access to water, have had negative impacts on community members’ standard of living, including rights to food, water, and work.

People resettled to the Vale resettlement village Cateme and the Rio Tinto resettlement village Mwaladzi experienced a major disruption to their livelihoods and are still struggling to re-establish their self-sufficiency. Human Rights Watch interviewed farmers in May and October 2012 who showed us their barren fields and empty food warehouses and said the farmland provided to them as compensation is unproductive, unsuitable for growing their staple crops of maize and sorghum, and unable to support their typical second harvest of vegetables. In contrast, several farmers awaiting resettlement to Mwaladzi, but still living in one of the original villages, had rich yields of vegetables from their plots along the Revuboé river.

Vale representatives have acknowledged that the land in the resettlement sites is arid and requires irrigation to improve its fertility, and a Rio Tinto communication to Human Rights Watch noted that they were “aware that the carrying capacity of the land in Mwaladzi is very marginal without irrigation schemes.” While Vale and Rio Tinto have implemented the resettlement of communities displaced by their operations, the Mozambican government is ultimately responsible for approving and allocating resettlement sites as well as monitoring their outcomes.

The choice in resettlement sites also had negative impacts on resettled households’ access to non-farming livelihoods. Cateme and Mwaladzi are located approximately 40 km from the markets in the district capital Moatize, whereas before resettlement the communities were a few kilometers away. The increased distance, limited transportation options, and the scarcity of baobab trees—a widely-used resource in their original villages—has reduced the communities’ ability to sell firewood, charcoal, and wild fruits, activities that many typically turned to when poor rains affected their crops or if they needed cash income. Jobs generated by Vale and Rio Tinto during their construction phases and available to resettled individuals were largely short-term contracts that have ended.

Compounding their problems with livelihoods, resettled households in Cateme and Mwaladzi have experienced serious problems with the availability and accessibility of water for both domestic and agricultural use. In the initial period after resettlement, water pumps in disrepair or ceasing to function due to electricity outages exacerbated overall problems with water availability. Households in Mwaladzi sometimes depended on water to be delivered by trucks and reported instances of having no water for three days at a time. Having once lived near the Zambezi or Revuboé rivers, the water problems in the resettlement sites represented a significant deterioration in the standard of living for many households.

Vale designed the urban resettlement village 25 de Setembro for households relying primarily on non-agricultural livelihoods. People who chose to move to 25 de Setembro did not receive any new farmland as part of their compensation packages, even if they had farmed previously. Human Rights Watch spoke to resettled residents who struggled with the transition from having both cash income and farming plots to relying solely on earning money to support their families. Individuals and households faced new costs in paying for food, and had not anticipated expenses such as paying for piped water, which a majority had previously obtained from a nearby river, pipes, or wells at no cost.

Female-headed households were often in particularly precarious economic situations, including elderly widows and single mothers who moved to 25 de Setembro primarily to be close to family members or health care services, not because they could rely on urban-based jobs. Human Rights Watch interviewed six women and heard reports of additional households in 25 de Setembro who resorted to living in their kitchens, sometimes with as many as six children, and renting out the houses given to them as compensation in order to earn enough money to buy food and water.

The provision of education and health infrastructure in Cateme has proceeded relatively smoothly. Vale financed a new primary school, residential secondary school, and health center. Due to delays in the resettlement schedule, residents of the Rio Tinto resettlement village Mwaladzi generally travel to Cateme for health care and for primary school. Limited transport, especially at night and on weekends, led to several women and girls in Mwaladzi delivering babies at home in 2011 and 2012 instead of in health care settings with skilled attendants. Their original villages had been close to the district hospital and transportation options in Moatize.

Other major complaints include the quality of housing. In the Vale resettlement sites of Cateme and 25 de Setembro, where new cement housing with zinc roofs was planned as an improvement over the wood huts many lived in before, poor construction led to cracks in the walls and heavy leaks when it rained. During the initial construction process, Vale also changed the agreed-upon design of the houses without adequate consultation and communication with the resettled communities and built them without foundations.

A detailed analysis of environmental impacts is beyond the scope of this report, however, coal mining is widely recognized as one of the most hazardous forms of natural resource extraction for human health and the environment. In the case of open-pit coal mines, these include air pollution, water pollution, land degradation, social impacts, and carbon emissions that contribute to climate change. The environmental impact assessments prepared by Vale and Riversdale note that the proximity of their coal mines to the populated settlements of Moatize and Tete city, as well as to the Zambezi and Revuboé rivers heighten the risk of negative impacts, especially in case of mitigation failures.

* * *

The Mozambican government has obligations under its national constitution and international human rights law to protect a range of rights, including to food, water, work, housing, and health. These obligations require the government to avoid any deliberate retrogressive measures that interfere with the enjoyment of these rights and to take measures to promote their progressive realization. For Mozambique, this means coordinating management of extractive industries with national poverty reduction strategies, strengthening protections for people resettled due to mining projects, and providing fair, timely remedies for those negatively impacted.

Private companies are required to respect these rights, including by conducting due diligence to prevent human rights abuses through their operations and mitigating them if they occur.

Both Vale and Rio Tinto have made private and public commitments to improve resettled communities’ standard of living. By early 2013, both had implemented projects to improve water supply and storage for domestic use and were studying ways to enhance availability of water for livestock and agricultural use. In July 2012, Vale signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the governor of Tete province to complete repairs and add foundations to all constructed houses, increase training opportunities, and provide ten fruit trees for each household in Cateme and 25 de Setembro.

Despite these improvements, provision of the full promised compensation and infrastructure improvements, including replacement agricultural land, adequate water supply, healthcare infrastructure, and restoration of livelihoods, have been delayed by months and in some cases years. According to international standards, resettled individuals have the right to their compensation, including access to services, established by the time of resettlement.

At least 83 families in Cateme effectively have had no access to farmland because their plots were filled with rocks or had been reclaimed by the land’s original users. As of April 2013, alternate compensation for this land was still being negotiated, but Vale said it had not yet provided these households with any additional compensation or assistance for their extra hardship in the three years since they were resettled.

As of April 2013, all resettled households in Cateme were still waiting for the provincial government to allocate a second hectare of farmland promised in their original compensation package in 2009. A second plot of land—if fertile—could greatly alleviate resettled communities’ problems in restoring their livelihoods and access to food. The difficulty in finding suitable farmland is particularly pronounced in Moatize district, where approximately 80 percent of the land has been designated for mining concessions and exploration licenses. At this writing, Vale officials told Human Rights Watch that the government had decided to change the terms of the compensation package and that Vale should provide resettled households in Cateme with money in lieu of the second hectare of promised farmland. This change raises a number of concerns, including the long-term sustainability of financial compensation if not invested in productive assets.

Map 4: Companies with Mining Licenses in Moatize District, Tete Province

Short-term solutions have included handing out food packages to residents of Cateme and Mwaladzi, and organizing intermittent food-for-work programs through a government agency. Vale provided food packages as compensation for disrupted harvests in 2009 and 2010, but despite the hardship that many households were facing in cultivating adequate food or earning money to purchase food, they did not provide additional food assistance until March 2012. Similarly, after giving households a three-month food package upon resettlement, Rio Tinto only began providing additional food assistance in September 2012. Lack of information about the timing and duration of food assistance have contributed to resettled households’ anxiety about food security and self-sufficiency.

Upon growing recognition of resettled households’ livelihood problems, Vale and Rio Tinto have initiated projects such as forming chicken cooperatives, encouraging people to farm new cash crops instead of their main staples, and exploring complex technological fixes to the endemic water problem, with proposals ranging from building a water-catchment dam to piping in water from the Zambezi river 60 kilometers away. Resettled households in Cateme and Mwaladzi may benefit from these initiatives, but they are also now dependent on “development” projects that could take years to come to fruition.

Local, provincial, and central government officials have acknowledged making some mistakes with the resettlements but say they have learned from the experience and will prevent similar problems in the future. Blaming Vale and Rio Tinto for many of the problems, the government says it should have played a stronger mediating role. It now requires a government representative to be present during meetings between communities and companies. While this practice can potentially play a protective role during negotiations and resolution of conflicts, it has also impeded more regular communication between companies and communities, and slowed the frequency of meetings and resulting action to resolve complaints.

District officials have also instructed resettled community leaders not to speak with civil society activists, journalists, and other agencies unless they secure prior approval and appropriate “credentials” from the district administrator. Withheld permission has prevented international agencies such as the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) from conducting research and programming in the resettled villages. Such actions undermine the right to freedom of expression.

The government has scrambled to institute a more comprehensive regulatory framework that should have been in place prior to the development of mega-projects and resettlements. On August 8, 2012, Mozambique’s Council of Ministers adopted a new decree regulating resettlements due to economic projects. The decree helps fill a critical gap and sets out basic requirements on housing and social service infrastructure. However, the government did not properly consult the public, civil society, the private sector, and international donors during its drafting, and the final version falls short of providing critical protections, relating, for example, to land quality, livelihoods, access to health care, and grievance mechanisms. The decree does not establish clear standards for access to water supply, timing of moves to avoid disruptions to farming cycles, and technical assistance for those who must adapt or change their livelihoods.

The government has increasingly pursued several other measures to manage extractive industries and their impact on the economy. This includes revising its mining law, for example, to require publication of new contracts and revising its fiscal regime to include taxation policies more favorable to the government. The 2013 Budget Law requires 2.75 percent of revenues from gas and mining to be set aside for community development projects for directly impacted populations. Mozambique has also become a compliant member of the international Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a voluntary initiative that works to enhance revenue transparency by verifying and publicizing the revenues paid to member governments by extractives companies.

These are positive measures for which the government deserves credit, yet more remains to be done. For example, communities affected by large projects need to be aware of their legal rights and should be able to participate meaningfully in decision-making at all stages of resettlement. Integrated planning to coordinate the cumulative economic, social, and environmental impacts of the natural resource boom and national poverty-alleviation efforts remains weak. And there is little transparency on how revenues from the mining and gas sector are used.

Mozambique is at a crossroads. Increased revenues coupled with careful planning and checks and balances have the potential to make significant contributions to the progressive realization of internationally protected economic, social and cultural rights. But without transparency, good governance including channels for complaints and remedies, and plans for inclusive growth, large foreign investments into natural resources can all too easily translate into huge profits for a few and harmful impacts for local communities most directly affected.

The Vale and Rio Tinto projects in Tete province are just the first in many large projects and resettlements likely to take place over the next few decades in Mozambique, making the lessons learned from current projects vitally important. New resettlements, including those planned by Jindal Steel and Power Limited and Rio Tinto will provide an important test of the effectiveness of evolving safeguards. The recommendations below highlight key steps that the Mozambican government and mining companies should take to remedy the plight of already resettled communities, and to strengthen protections moving forward.

Recommendations

To the Government of Mozambique

The governor of Tete province, in coordination with the relevant central, provincial, and local officials, should work with resettled communities, Vale, and Rio Tinto to ensure the provision of immediate relief and longer-term measures to remedy the violations of the rights of resettled individuals, and ensure the enjoyment of key economic, social and cultural rights. These include:

Ensuring that each resettled household in Cateme and Mwaladzi, prior to the next farming season, has the promised two hectares of cleared farmland that meet the criteria of adequate fertility, access to water, capacity to grow their staple crops, and location within a reasonable distance:

- Allocate the second hectare of farmland promised to residents of Cateme as part of their compensation package. If offering financial compensation instead, do so in a way that promotes productive capacity and economic self-sufficiency, such as supporting an assisted indemnification process in which Vale and the government help resettled individuals to identify and acquire a suitable plot of land or to invest in other productive assets.

- Prioritize the completion of sustainable water and irrigation projects to improve the fertility of the farmland in the resettlement sites.

Designating and adhering to a reasonable timeframe for implementing measures requiring government approval and action, including by revising and updating current Resettlement Action Plans and related Memoranda of Understanding.

- Establishing a timeline and ensuring company compliance to complete all needed infrastructural improvements in Cateme, 25 de Setembro, and Mwaladzi, including with respect to housing, health, roads, transport, markets, electricity, and water for consumption, domestic use, and agricultural use.

Implementing strategies for developing alternative income-generating activities in close consultation with resettled communities, including by:

- Ensuring equality of opportunity for both women and men during recruitment and training for employment opportunities, including those generated by coal mining and affiliated businesses;

- Identifying and providing additional assistance to particularly vulnerable individuals, including the elderly, people living with disabilities, and female-headed households; and

- Including clauses in project contracts and resettlement action plans targeting local communities in business supply chains, such as food supply.

Ensuring the distribution of regular food assistance and other forms of support so that resettled communities are able to meet their immediate needs until conditions for self-sufficiency are restored.

Ensuring provision of compensation for the delays and shortcomings in establishing appropriate conditions in the resettlement sites that led to violations of resettled individuals’ rights, including but not limited to:

- Providing appropriate compensation to the 83 households in Cateme that have not had access to a suitable plot of farmland since their resettlement because the first hectare provided was too rocky or was reclaimed by the land’s original users.

Mozambique’s government, including the Ministry of Mineral Resources, the Ministry of Coordination of Environmental Action, and the relevant local and provincial authorities, should review, and if necessary, halt, the process of awarding prospecting licenses and mining concessions to ensure that appropriate sites for resettlement are available when necessary, and to permit planning for cumulative social, economic, and environmental impacts.

The government of Mozambique should revise the August 2012 resettlement decree with broad consultation among relevant stakeholders, including the public, companies, donors, academics, and civil society. A revised decree should:

Include the principle that resettlement be avoided when possible, only after exploring possible alternatives, and to minimize its scope and impact when it takes place.

Ensure regular, broad, and meaningful public consultation and participation at all stages of resettlement, including through:

- Meaningful consultation in the design, implementation, and post-move phases of resettlement;

- The full, prior, and informed consent of affected individuals regarding the relocation site;

- Consideration of alternative plans proposed by affected persons and communities;

- Provision of viable alternatives so that affected communities can make real choices in their best interest instead of having to accept one standard compensation package;

- Participation restricted not only to public hearings, but coupled with other forms of dialogue, including individual and small group consultations;

- Establishment of accessible channels for providing feedback outside the framework of planned consultations; and

- Dedicated measures that facilitate the participation of groups that may face specific impacts or that are marginalized such as women, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and minorities.

Elaborate clear guidelines for reestablishing and improving the resettled population’s standard of living, with as minimal disruption as possible, including livelihoods and access to services such as health care and education. These guidelines should ensure that:

- Affected populations have the right to receive any promised financial compensation prior to resettlement;

- Compensation—including the means of livelihoods and promised infrastructure such as housing, schools, health posts, and roads—should be established prior to relocation to minimize disruptions to the resettled population’s standard of living;

- Compensation packages contribute to the progressive realization of the availability, affordability, accessibility, and quality of health care, housing, and education;

- Resettlements involving the allocation of agricultural land meet minimum requirements for the type and quality of replacement land, access to water supply, provision of technical assistance for communities adapting or changing their livelihoods, and consideration of farming cycles in the timing of resettlement;

- Compensation packages address economic means and activities such as home vegetable gardens, transportation, and access to key markets; and

- The standards on housing should allow for the expression of cultural identity, practices, and diversity,

- Surveys of registered beneficiaries and their compensation should be updated prior to resettlement to accommodate recent marriages, separations, births, and deaths.

Provide accessible mechanisms for grievance redress.

- Establish accessible channels and mechanisms for various stakeholders to make complaints or resolve disputes related to the resettlement process, and to receive responses to their complaints;

- Conduct public awareness campaigns among communities to be resettled to inform them of their legal rights throughout the process;

- Ensure existing channels for seeking redress through Mozambique’s justice system are available to parties affected by resettlement; and

- Require companies to establish effective grievance mechanisms so that individuals affected by mining projects can complain directly to the companies in addition to the government.

Conduct robust monitoring, including inspections, to ensure implementation of the decree and accountability.

Mozambique’s government, including the Ministries of Finance, Mineral Resources, Coordination of Environmental Action, Planning and Development, and Agriculture, should strengthen measures for governance, transparency, and respect for human rights in its management of the boom in large-scale investments and associated economic development plans.

The relevant government entities at the central, provincial, and local levels, should evaluate and monitor the cumulative economic, environmental, human rights, and developmental impacts of mining, gas, agricultural, and other large investments.

- The Ministry of Mineral Resources should coordinate with other appropriate government sectors, including at the provincial and local level, about the number, speed, and scale of coal concessions being awarded in Tete province to minimize impacts on local communities, including harmful environmental impacts, involuntary resettlements, reduced availability of appropriate land for resettled populations, and the effective functioning of general infrastructure and social services.

The government of Mozambique should improve its regulation and monitoring of large-scale investments and impose penalties in case of violations, including by:

- Adopting the proposed revisions to the 2002 mining law which require publication of contracts, time limits by which investors must begin mining operations upon acquisition of a license, and adherence to regulations on environmental and social impacts;

- Developing, through a process of broad consultation, and adopting a policy for corporate social responsibility in the extractives industry that meets the international human rights standards laid out in the “Protect, Respect, and Remedy” framework;

- Increasing the Ministry of Coordination of Environmental Affairs’ recruitment and retention of trained staff to analyze environmental impact assessments (including resettlement action plans), monitor compliance reports, and form inspection teams to verify that companies adhere fully to their commitments; and

- Participating in partnerships and informational exchanges with other governments and institutions with relevant experience in ensuring human rights safeguards in managing natural resource booms, including institutions able to provide independent monitoring.

The government of Mozambique should protect the rights to information, freedom of expression, and community participation, and improve transparency, including by:

- Ending any measures that interfere with resettled communities’ right to free speech, assembly, and access to information, including by ending bureaucratic requirements for NGOs, journalists, UN agencies and others to obtain “credentials” before speaking to village leaders in Tete province;

- Protecting freedom of speech, including critical opinions and public statements on economic development projects and their execution, and the right to peaceful protest;

- Including representatives of civil society and affected communities on provincial resettlement commissions;

- Providing public information on the role and tasks of the provincial resettlement commission;

- Ensuring wide public access to regular, timely information that tracks the use of revenue flows from extractive industries; and

- Requiring companies that prepare environmental impact assessments, environmental monitoring reports, and resettlement plans to make these documents easily available and accessible to the public, including by providing short summaries in non-technical language, translating the summaries and the full reports into local languages, posting them on the internet, and providing copies in public buildings such as local schools in directly affected communities.

To Vale and Rio Tinto

Vale and Rio Tinto should work with resettled communities and appropriate representatives of the Mozambican government, including the governor of Tete province, to provide immediate relief and longer-term measures to remedy the negative impacts on the rights of resettled individuals. These include:

Working to ensure that each household in Cateme and Mwaladzi has cleared farmland of suitable fertility and quality for growing their staple crops, including by:

- Working with the Mozambican government proactively and as a matter of high priority to replace all currently-allocated plots of poor agricultural value with suitable ones;

- Working with the Mozambican government to allocate the second hectare of farmland promised to residents of Cateme as part of their compensation package;

- Where financial compensation is to be provided, do so in a way that promotes productive capacity and economic self-sufficiency, such as an assisted indemnification process in which Vale and the district government can help resettled individuals to identify and acquire a suitable plot of land or to invest in other productive assets;

- Prioritizing the completion of sustainable water and irrigation projects to improve the fertility of the farmland in the resettlement sites; and

- Continuing technical assistance to improve agricultural yields.

Vale and Rio Tinto should work with resettled communities to develop a clear action plan to provide immediate relief and longer-term measures to remedy the negative impacts on the rights of resettled individuals.

- Provide timely and appropriate compensation for the delays and shortcomings in establishing appropriate conditions in the resettlement sites that led to violations of resettled individuals’ rights.

- Provide timely and appropriate compensation to the 83 households in Cateme that have had not had access to a suitable plot of farmland since their resettlement because the first hectare provided was too rocky or was reclaimed by land’s original users.

- Distribute regular food assistance and other forms of support so that resettled communities are able to meet their immediate needs until conditions for self-sufficiency are restored.

- Survey resettled households on key indicators of standard of living to establish the extent to which they enjoy basic social and economic rights until these have been restored at minimum to the guidelines in the resettlement decree, their pre-resettlement levels, and goals outlined in the resettlement action plans, and make these findings publicly available.

- Ensure equality of opportunity for both women and men during recruitment and training for employment opportunities, including those generated by coal mining and affiliated businesses.

- Identify and provide additional assistance to individuals having the most difficulty reestablishing their former standard of living, including the elderly, people living with disabilities, and female-headed households.

- Complete needed repairs on all houses in a timely manner. Keep resettled households informed about the timeline of repairs and train them on maintenance and upkeep.

To All Investors, including Vale, Rio Tinto, and Jindal Steel and Power Limited

Ensure that future resettlements comply with international human rights standards in their design, implementation, and follow-up.

Improve public access to information and transparency by:

- Strengthening channels of communication with local and national civil society and with community members affected by resettlement; and

- Making documents such as environmental assessments, periodic environmental monitoring reports, resettlement action plans, and updates on implementation more accessible, including by providing short summaries in non-technical language, translating the summaries and the full reports into local languages, posting them on the internet, and providing copies in public buildings such as local schools in directly affected communities.

Establish effective grievance mechanisms so that individuals affected by mining projects can complain directly to companies in addition to the government.

Support efforts to improve Mozambique’s management of the individual and cumulative impacts of economic development projects and exploitation of natural resources.

Support research on cumulative, long-term economic, social, environmental, and human rights impacts.

To the Governments of Brazil, India, Australia, the United Kingdom and Other Home Governments of Mining Firms Operating in Mozambique

Take steps to regulate and monitor the human rights conduct of domestic companies operating abroad, such as requiring companies to carry out and report publicly on human rights due diligence activity.

To the G19 Donor Group, including the World Bank

Support increased capacity of the government at the central, provincial, and district levels to manage the growth in extractive industries, by:

Expanding research and public dialogue on managing the natural resource boom to meet economic and social development goals.

- Consider the creation of an annual conference to bring together Mozambican government officials, representatives of extractive industries, academics, members of affected communities, civil society activists, donors, and other stakeholders to learn from ongoing efforts and to incorporate lessons into future planning and monitoring.

- Create spaces for permanent tripartite dialogue around resettlement processes at the provincial level, including businesses, civil society and members of resettled communities, and relevant provincial and district authorities.

Building capacity of provincial directorates and local administration.

- This includes training and support for implementation of land use laws, monitoring the environment, integrated planning, and management of resettlements.

Funding scholarships, trainings, and international exchanges for civil society activists, journalists, academics, and government officials to build capacity to negotiate and monitor mega-projects.

Engage in political dialogue with government on the impact of the extractives sector on development and human rights, including through developing relevant indicators for evaluation during the annual donor review.

Support increased transparency and accessibility of information about the extractives sector to directly affected communities, civil society, the broader public, and the media.

Establish an annual review of transparency in the extractives sector, including indicators such as publication of contracts, resettlement plans, environmental assessments, a breakdown of revenue flows, and memoranda of understanding as well as dissemination of laws and policies and information about rights.

Create a publicly available and easily accessible document mapping the amounts of donor funding focused on the extractives sector, the types of projects, and their outcomes.

Provide financial and technical support to civil society institutions to strengthen their coordination and monitoring of the government and the private sector in their fulfillment of their obligations to protect and respect human rights, including by:

Supporting them to work with communities to obtain a delimitation of their lands before resettlement to clarify their land rights.

Supporting them to work with resettled communities at all stages of resettlement, including early stages to ensure awareness of their legal rights and during and after the move to improve access to complaints mechanisms.

Supporting their capacity to conduct research and report on the adherence of the government and mining companies to human rights obligations.

Enhance own resettlement policies to meet international human rights standards and ensure that all activities funded by members of the G19 Donor Group, including the World Bank comply with these standards.

To the International Monetary Fund

Establish, in coordination with other donors, an annual review of transparency in the extractives sector, including indicators such as publication of contracts, resettlement plans, environmental assessments, a breakdown of revenue flows, and memoranda of understanding as well as dissemination of laws and policies and information about rights.

Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted in Mozambique in January, May, and October 2012. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews in three communities (Cateme, 25 de Setembro, and Mwaladzi) in Moatize district, Tete province that had been resettled by the coal mining companies Vale, Riversdale, and Rio Tinto. We also visited two communities in Moatize district (Capanga) and Changara district (Cassoca) that were in the process of being resettled by Rio Tinto and Jindal Steel and Power Limited.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with 79 community members (55 women and girls and 24 men and boys) affected by resettlement, including 41 interviews using a detailed survey. Twenty-six of the survey interviews took place in resettled communities and 15 in communities about to be resettled. Five of the general interviews included village-level leaders, and five interviews were with children between the ages of 14 and 17. We interviewed ten people twice, in both May and October, to gauge any change in their situation.

Human Rights Watch researchers discussed with all interviewees the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, the ways the information would be used, and that no compensation would be provided for participating. Interviews typically lasted between 20 minutes and one hour.

The survey questionnaire covered demographic information and detailed questions about land, water, livelihoods, housing, and hunger. The questionnaire was tested and translated into both Portuguese and the local language, Nyungwe. Human Rights Watch researchers divided up the villages geographically by their neighborhoods and interviewed households in each geographic area. If a respondent was not home or declined to participate, the researcher would move on to the next adjoining house on the same side of the street. While the sample used in the survey is not a statistically representative sample, it presents an indication of general living conditions for affected communities.

Human Rights Watch researchers held numerous meetings and telephone conversations with representatives from Vale, Rio Tinto, and Jindal Steel and Power Limited, including country directors in Maputo, and mine managers and community development advisors in Tete province.

We also held meetings with the Mozambican government at the district, provincial, and central levels. These include Moatize’s district administrator and Tete province’s permanent secretary, provincial director of mining and energy, and provincial director of environmental action. At the central level, we met with the minister for mineral resources, the deputy minister of the national mining directorate, the deputy minister for coordination of environmental affairs, the permanent secretary for planning and development, and ministerial advisors in the Ministry of Women and Social Affairs.

We spoke with 31 representatives of human rights, women’s rights, development, and environmental NGOs, including Associação de Apoio e Assistência Jurídicas Comunidades (AAAJC), Associacão para a Sanidade Ambiental (ASA), Liga dos Direitos Humanos, and Centro de Integridad Pública (CIP). We also met with eight representatives of UN agencies, donors, and multilateral institutions, including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme, the embassy of Norway, and the World Bank. Finally, we additionally held three roundtable discussions with members of the G19 Extractive Industries Taskforce, including representatives from Finland, France, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and UN Women, and two roundtable discussions with members of Mozambican civil society in Maputo and Tete.

The vast majority of interviews with community members were conducted in the local language, Nyungwe, with direct translation into English. Some interviews, including with government officials, donors, and company representatives were conducted in English, and other interviews were conducted in Portuguese with English translation.

We have used pseudonyms with a first name and second initial throughout the report for many of the interviewed community members in the interest of their privacy. Other interviewees preferred to have their real names used.

This report also draws on synthesis and analysis of licensing data collected from Mozambique’s mining cadaster in May and October 2012 and satellite imagery. Background research included analysis of Mozambique’s legal framework, review of existing literature, and press monitoring.

I. Mozambique and Foreign Investment

Poverty and Growth

On October 4, 2012, Mozambique celebrated twenty years of peace after a long struggle for independence and a bloody civil war killed nearly one million people, displaced five million, and decimated the country’s infrastructure.

Many international donors, development agents, and the media herald Mozambique as an “African success story,” pointing to a lasting peace after decades of conflict and sustained economic growth.[1] While Mozambique has made some significant social and economic gains, including increases in school enrollment rates and a drop in maternal mortality, it remains one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 185 out of 187 countries on the 2012 UN Human Development Index.[2]

Mozambique’s gross domestic product registered annual growth rates between 6.3 and 8.7 percent from 2003 to 2012, [3] but this growth has not been accompanied by significant poverty reduction or a rapid improvement of key health and social indicators. [4] More than half the population remains below the poverty line, and malaria, HIV, and perinatal diseases account for the top three causes of death. [5] An estimated 11.3 percent of the population between ages 15 and 49 are living with HIV/AIDS. Forty-five percent of adults and children at an advanced stage of HIV infection were on antiretroviral therapy as of 2011. [6] Nationally, 42.6 percent of children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition, and this figure rises to 44.2 percent in Tete province, the home of Mozambique’s vast coal reserves. [7]

Mozambique depends heavily on international donor funds, coordinated through the Programme Aid Partnership (PAP), a consortium of donors commonly referred to as the “G19.”[8] This is one of the largest coordinated donor initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa, both in terms of the volume of funds and the number of donors.[9] In 2013, the PAP committed to provide Mozambique with US$606 million, of which $344 million will be direct budget support.[10] The proportion of donor funds in the national budget is starting to decline due to Mozambique’s increasing revenues from its emerging extractive sectors, donor frustration with insufficient government action on corruption and effectiveness, and donors’ economic pressures domestically.[11]

Coal Mining Investments in Tete Province

Mozambique is rich in natural resources, including coal, natural gas, agricultural land, bauxite, and phosphates. The government, with support and technical assistance from international financial institutions, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, has wooed foreign investment since the 1990s.[12]

Discoveries of high-grade coking coal—used in steel production—coupled with rising demand from China, India,[13] and Japan[14] have contributed to a surge in investor interest despite concerns about Mozambique’s weak infrastructure, including limited rail capacity to transport coal from mines to ports. Mozambique’s Tete province has among the largest untapped coal reserves in the world, estimated at more than 23 billion tons of coal.[15]

In the last ten years, foreign companies have invested billions of dollars in coal exploration, infrastructure development, and coal mining activities. Foreign investors in Tete province’s mining sector rank among the largest mining companies worldwide: Vale, a Brazilian multinational company and Rio Tinto, an Anglo-Australian multinational company have secured concessions to vast coal reserves and have already begun their mining operations. Jindal Steel and Power Limited, an Indian company, and Beacon Hill Resources, a British company, have also started coal mining on a smaller scale.

Other licenses are held by Minas de Revuboé (jointly owned by Anglo-American Talbot Group, Nippon Steel, and POSCO) and the Mozambican state company MozambiCoal, along with local partners, though it is still in an early exploration and prospecting phase. MozambiCoal has title to explore the richest coal regions near Mutarara in Tete province, with combined estimated reserves of over 6 billion metric tons[16] (see Appendix A for a list of coal mining concessions in Tete province, their size, and expected coal output).

Several civil society groups and academic experts in Mozambique have criticized the pace of growth in Tete province’s coal industry and questioned the social and economic benefits for the country. [17] Their critiques include the lack of transparency around the terms of the first mining contracts, limited information about how revenues will be tracked and used, and a lack of government monitoring mechanisms to ensure that companies comply with the environmental and social commitments they made. [18] They also express concern about the Mozambican government’s capacity to manage the scale and speed of these investments.

Environmental Impacts

A detailed analysis of environmental impacts is beyond the scope of this report. However, coal mining is widely recognized as one of the most hazardous forms of natural resource extraction for human health and the environment. The government has the responsibility to regulate and monitor such impacts, including with respect to the cumulative impact of individually approved mining projects.

Coal mining releases harmful carbon emissions into the atmosphere, including methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide, greenhouse gases recognized as leading causes of climate change and estimated to account for 71 percent of the global warming impact triggered by human activities.[19] Open-pit mining involves clearing of trees, plants, and topsoil, and can destroy natural wildlife habitats and local biodiversity.[20]

Coal mining also leads to water and air pollution. Dust and coal particles resulting from mining—as well as soot released during coal transport—contributes to air pollution that may cause severe and potentially deadly respiratory problems to both mine workers and community members living in close proximity to mining sites.[21] Coal exposed to air and water leads to acid mine drainage—acidic run-off containing toxic material such as copper, lead, mercury, and other heavy metals.[22] This contaminated water can leach into nearby rivers, streams, and groundwater, further jeopardizing the health and livelihoods of local communities.[23]

The Environmental Impacts Assessments (EIAs) submitted by Vale and Riversdale (later acquired by Rio Tinto) describe the anticipated environmental impacts of their mining projects as well as plans to mitigate them. [24] Human Rights Watch did not investigate the impacts of Vale and Rio Tinto’s operations, however, several aspects are worthy of further scrutiny. These documents note that the proximity of both the Moatize and Benga mines to the populated settlements of Moatize and Tete city, as well as to the Zambezi and Revuboé rivers raise the risk of negative health and economic impacts, especially in the case of mitigation failures.

For example, Vale officials and the Riversdale EIA both mentioned that communities on the outskirts of Tete city are directly in the path of air pollution carried by prevailing winds.[25] In one phase of the Benga mine operations, “hourly average NO2 concentrations exceed WHO guidelines of 200 ug/m3, but is within the Mozambican legal limit of 400 ug/m3.”[26] The EIAs for both the Moatize and Benga mines discuss numerous sources of potential water contamination as well as land degradation.[27]

Although environmental assessments are supposed to be publicly available, in practice they are not easily accessible. When Human Rights Watch conducted its research in 2012, most of the civil society activists and donors to whom we spoke said they had not been able to obtain copies of the EIAs or Resettlement Action Plans. Furthermore, EIAs, as well as subsequent six-month environmental monitoring reports are lengthy, technical documents that are not easily digestible for the public, including affected communities, the media, and civil society. Aside from initial community consultations while preparing the EIAs, Human Rights Watch did not learn of any information dissemination strategies by either the government or by mining companies regarding ongoing and future environmental impacts.

The Mozambican government is still in the process of building its capacity to oversee the environmental implications of the rapidly growing extractives sector. This has included introducing new regulations on environmental emissions and penalties.[28] Ana Chichava, deputy minister of the Ministry of Coordination of Environmental Affairs, said, “The limitation is resources. We have to build the capacity of our staff…. We are investing in training people, but we are also losing some. We are trying to bind them with scholarships, but there is a lot of competition with the private sector because of salaries.”[29]

Transparency Concerns

The government should renegotiate and publish the contracts so as to alter the bleak picture characterised by the low contribution made by the mega-projects to state revenue, and the secrecy surrounding the contracts.

—Center for Public Integrity, Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative: Mozambique moves towards Compliant Status, 2012

Mozambique’s central bank reported that coal had risen to become Mozambique’s second largest export in 2012, after aluminum, with US$196 million in exports in the first half of 2012.[30] The question of whether Mozambique is receiving a fair share of revenue from large economic investments as well as the risk of conflicts of interest and corruption, have been the subject of intense debate. A donor told the Financial Times, “It’s a race against time – is the big money that corrupts going to come before stronger checks and balances?”[31] The Mozambican public has been limited in its ability to participate meaningfully in these discussions because of the lack of transparency and limited opportunities for dialogue.[32]

Mozambique’s Council of Ministers adopted revisions to the 2002 mining law in December 2012 to address some of these issues and these have been submitted to parliament. [33] As of April 1, 2013, these had not yet been passed into law. The existing mining law has few detailed requirements that companies must meet in order to obtain, and retain, a mining license. The proposed revision would require mining companies to publish their contracts. [34] The revision would also set the standard rate of taxes and royalties to be paid instead of leaving it subject to negotiation by each individual project proponent. To avoid speculation and land remaining unused, the proposed revision also requires investors to begin mining activities within 12 months of being awarded a concession, and to begin mining production within 48 months. [35]

In an effort to attract investment, the government gave early investors, including Mozal, an aluminum producer, and Sasol, focused on natural gas, favorable fiscal incentives.[36] The terms of these contracts have not been made public. Many civil society groups have condemned the lack of transparency around these investments and have questioned whether the government signed away important revenue-generating opportunities.Several civil society groups have called for the publication and renegotiation of these contracts.[37]

Recently, the government has been engaged in a process of strengthening the fiscal regime. For example, effective January 2013, foreign companies selling local assets will have to pay the government a 32 percent capital gains tax. Civil society organizations had critiqued gaps in the government’s fiscal regime, including a missed opportunity in 2011 when Rio Tinto acquired Riversdale for $4 billion but did not have to pay any taxes.[38]

In another bid to heighten transparency, Mozambique became a candidate in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2009. The EITI is a voluntary international initiative that brings together governments, extractives firms, and civil society groups to increase transparency around the revenues participating governments earn from extractives industries. Under EITI, member companies and governments each publish their figures on the revenues paid to governments by extractives firms, in order to help ensure that those figures are both transparent and accurate.[39]

The EITI board designated Mozambique’s first report, covering company payments and government revenues in 2008 and submitted in February 2011, as making “meaningful progress” but falling short of compliance with EITI standards.[40] The EITI board highlighted concerns related to the inclusion of all relevant entities in the reporting process and the full disclosure of all material oil, gas, and mining payments made by companies and revenues received by the government. The board also requested that government disclosures be based on audited accounts that meet international standards.[41]

Mozambique incorporated these recommendations and submitted a second report in March 2012 that covered company payments and government revenues in 2009. The EITI board designated Mozambique as an EITI compliant country on October 26, 2012.[42] Mozambique must produce an EITI report annually and undergo another validation process in 2017 to retain this status.

Debates on the Natural Resource Boom and Poverty Reduction

Mining projects can have both positive and negative impacts on local communities. Benefits may include job creation and improved infrastructure, but downsides can involve migration that drives up prices for goods and services, or growth in inequalities and social conflict.[43] Because open-pit coal mines rely on skilled labor and heavy machinery, they do not necessarily generate significant direct employment opportunities for local or directly impacted communities.

The greatest potential revenue may come from several discoveries of natural gas along Mozambique’s coastline, with estimates of up to 130 trillion cubic feet of offshore gas.[44] With regard to natural gas, the minister of mineral resources, Esperança Bias, says the country hopes to attract US$50 billion of investment in the next ten years and to earn $5.2 billion in government revenues a year by 2026.[45]

Manufacturing and extraction of natural resources are sectors of increasing importance in Mozambique’s economy, but agriculture and fishing remain central to many Mozambicans’ livelihoods and to poverty reduction, with 80 percent of the population counting these activities among their sources of income.[46] The government has prioritized strengthening of agriculture and fisheries as a principal strategy for targeting poverty in its 2011-2014 Poverty Reduction Plan. However this plan does not address integrated planning with the rapidly growing extractives sector or the issue of widening inequalities between the rich and the poor and between urban and rural populations.[47] In an academic study of development in the Zambezi basin commissioned by Vale, the authors note that,

the potentially transformative extractive industry is still a recent phenomenon. Without targeted investments in rural development, the urban-rural income divide will worsen and likely give rise to political and social unrest. Mining regions generally suffer from economic disruptions such as a surge in demand-driven prices and, especially, food prices.[48]

Similarly, a 2012 International Monetary Fund (IMF) report that examined natural resources exporters in sub-Saharan Africa, including Mozambique, noted that much of the income from capital-intensive extractive industries flowed to foreigners, highlighting the importance of licensing and taxation policies for countries to benefit from increased revenues. Even then, while “natural resource exporters have experienced faster economic growth than other sub-Saharan African economies during 2000–12 ... the improvement in social indicators is not noticeably faster.”[49]

Mozambique has begun to engage with these issues. In 2007, Mozambique amended its tax laws to include provisions specific to the mining and petroleum industries.[50] Article 19 of Law 11/2007 requires the government to invest a specific percentage of mining revenues—to be determined in the annual state budget—into community development projects for areas directly impacted by mining projects.[51] The 2013 budget fixed the percentage at 2.75 percent.[52] The government is also currently debating the establishment of a sovereign wealth fund, modeled after other resource-rich countries such as Norway, Brazil, and Angola, that would harness the revenues from mining and gas for broader national development.[53]

II. Coal Mining and Resettlement of Local Communities

This section provides information about the size and estimated timeline of major coal mining operations in Tete province and the associated plans for resettling local communities.

In order to secure the right to develop and operate a coal mine, companies must first obtain an exploration mining license to assess the reserves of coal in a designated area, study the feasibility of mining operations, and then obtain a "mining concession." The mining company should conduct an environmental impact assessment (EIA), including an evaluation of social impacts. An approved EIA is necessary for an environmental license, which along with a DUAT (a permit for the right to land use) are required for the mining company to retain its mining concession.[54] If the company plans to resettle existing local communities to develop coal mining operations, they must draw up a Resettlement Action Plan (RAP), including a detailed profile of the communities, farms, and infrastructure to be displaced and the design of the compensation package.

Vale

Vale Mozambique Ltd. (Vale) is a subsidiary of the Brazilian company Vale, which is the second largest mining company worldwide and listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Vale obtained permission from the Mozambican government to explore for coal in 2004 and a 35-year mining concession for 25,000 hectares in Moatize district of Tete province in 2007. The Mozambican government approved Vale’s EIA in 2007 and a revised EIA incorporating a planned expansion in 2011. Vale began construction on its “Moatize” mine in 2008, resettling households in 2009, and mining coal in May 2011.[55]

The scale of the project is massive in the context of Mozambique’s economy, which has a gross domestic product (GDP) of US$12.8 billion.[56] Vale spent between US$1.9 to 2 billion in its first phase, another two billion in its second phase, and an additional four billion in supporting infrastructure, including transport links.[57] Vale hopes to export up to 11 million tons of coal per year in its first phase and ramp up to 22 million tons per year in its second phase.[58] Vale cut its export target from 5 million tons to 2.6 million tons in 2012, citing capacity constraints on the Sena railway line connecting the mine and the port in Beira.[59] It is also upgrading the Nacala railway line and port to handle its increased coal production in the future.[60]

The terms of the mining concession enable the government to reserve the right to 25 percent of the shares. In 2012, the government acquired 5 percent of shares in the venture, although it did not disclose how much it paid, and reserved an additional 10 percent for private Mozambican investors.[61]

Vale’s Moatize mine and expansion involved moving 1,365 households living in and near the villages of Chipanga, Bagamoyo, Mithete, and Malabwe into two resettlements or providing them with other forms of compensation. Vale resettled 289 families into 25 de Setembro, designed as an urban neighborhood in the town of Moatize. Compensation did not include agricultural land, but included water pumps at each house, a promise to refurbish Moatize’s elementary school and hospital, and new houses. This resettlement was meant for individuals relying primarily on wage jobs instead of farming. Vale resettled 716 families into Cateme, a rural resettlement designed for farmers located approximately 40 km from Moatize. The compensation included new houses, neighborhood pumps, an elementary school, secondary school, health clinic, and a promised two hectares of farmland. [62]

For those who did not wish to move to either 25 de Setembro or Cateme, Vale provided 106 households with assistance to buy a new house and another 254 households with direct financial compensation, often in the case of people who already owned another house. Vale officials told Human Rights Watch they did not advertise prominently the possibility of direct or indirect financial assistance for fear that affected communities would spend all of their money quickly and then be left in vulnerable conditions without proper housing and land.[63]

After lingering problems with the resettlements of Cateme and 25 de Setembro in 2012, described more fully below, Vale and the Mozambican government signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in which Vale agreed to complete repairs and add foundations to all constructed houses, improve the water supply system, increase training opportunities, and provide ten fruit trees for each household in Cateme and 25 de Setembro.[64]

Rio Tinto and Riversdale

Riversdale Moçambique Limitada (Riversdale) is a subsidiary of the Australian company Riversdale Mining, which is listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. Riversdale acquired rights to prospect for coal in Tete province and after government approval of its EIA and Resettlement Action Plan for the “Benga” coal mine, began resettling affected communities in 2011.

In 2011, the Anglo-Australian firm Rio Tinto, one of the largest coal mining companies worldwide with a presence in forty countries, acquired Riversdale, including its multiple coal concessions in Tete province. These include the “Zambeze” project (estimated 9 billion metric tons), the “Tete East” project (estimated 5 billion metric tons) and the furthest developed Benga project (estimated 4 billion metric tons). In 2013, Rio Tinto revised the estimates of recoverable coal downward.[65] The Indian company Tata Steel owns a 35 percent stake in the Benga mine.

Riversdale had already designed the resettlement action plan (RAP) when it was acquired by Rio Tinto. Fernando Nhantumbo, Rio Tinto’s manager for social relations, said, “Riversdale made the RAP, not us. But when you buy something you are bound to what was there before. We had 100 to 200 houses already complete and some people already resettled. But we are looking at where we should improve on the policies Riversdale had in place.”[66] In 2012, Rio Tinto conducted an analysis to compare the Riversdale RAP and resettlement performance with its standards to produce an updated plan and bridge gaps.[67]

The Benga project included resettlement of a total of 679 households living in or near the villages of Capanga and Benga. Of these, 472 are being resettled to a newly-constructed village named Mwaladzi, which adjoins the Vale resettlement village of Cateme. Although 84 households moved to Mwaladzi in 2011 and 2012, delays in establishing adequate resettlement conditions stalled the operation. Rio Tinto told Human Rights Watch it expected to resettle the remaining 388 households by May 2013. [68]

The compensation package for those moving to Mwaladzi included a newly constructed house, a primary school, two hectares of cleared land per household, and neighborhood water pumps. After complaints by resettled community members, Rio Tinto also financed a health post and an ambulance operating on weekdays.

The company also compensated some non-farming households with combinations of direct payments and support for buying houses in and around Tete city and Moatize. [69] Rio Tinto began mining and exporting coal from its Benga mine in 2012.

Jindal Steel and Power Limited

Jindal Steel and Power Limited Mozambique (JSPL) is a subsidiary of Jindal Steel and Power Limited, an Indian mining company listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange. JSPL’s “Chirodzi” concession has an estimated 724 million tons of coal reserves and is located in Changara district, Tete province. The company estimates it will invest US$180 million in the project. The government has a 10 percent stake.[70] JSPL obtained the concession in 2011 and began mining coal in 2012.

As its mining activities expand and upon securing approval for its Resettlement Action Plan, JSPL will carry out resettlements of affected communities. JSPL plans to resettle 2,050 people in 484 directly affected households from the villages of Cassoca (including Xissica) and Nhomadzinedzani into newly-constructed houses and farms.[71] As of mid-April 2013, the proposed relocation site had yet to be formally approved by the government. Another 968 households from Chirodzi, Chirodzi-Ponte, and Nhatsanga-Ponte will lose their farmland to the mining operations but not their homes. JSPL plans to compensate them with replacement land.

JSPL has initiated some projects in the affected communities already, including building an elementary school in Chirodzi, improving the access road from the main highway to Cassoca village, and providing water pumps. As of mid-April 2013, the timeline for resettlement remained uncertain.

Table 1: Resettlements due to Coal Mining in Tete province

|

Company |

Name of Mine |

Original Village |

Resettled Village |

|

Vale |

Moatize |

Chipanga, Bagamoyo, Mithete, Malabwe |

Cateme, 25 de Setembro |

|

Rio Tinto |

Benga |

Capanga, Benga, Nhambalualu |

Mwaladzi |

|

Jindal Steel and Power Limited |

Chirodzi |

Cassoca, Xissica, Nhomadzinedzani |

Not yet resettled |

III. Problems with the Vale and Rio Tinto Resettlements

We are just suffering here. Where they moved us from—there we had enough food to eat and here we do not. There we could do something to earn money and here we can do nothing.

—Eulália Z., resettled woman with three children, Mwaladzi, May 11, 2012

Households in the three communities resettled by Vale, Riversdale, and Rio Tinto (25 de Setembro, Cateme, and Mwaladzi) have experienced significant disruption in the enjoyment of several economic and social rights, including their ability to obtain adequate food and water, and access work and health care. While Human Rights Watch does not have comprehensive data on the outcomes for each resettled family, the agricultural land given to many residents resettled to Cateme and Mwaladzi is recognized by the authorities and companies interviewed by Human Rights Watch as having deeply uneven quality and not having access to enough water to be fertile.

Communities also have reduced options for non-farming work and an erratic water supply. They now live approximately 40 km from a major market compared to a few kilometers before resettlement. While new cement housing provided in the three resettled communities was planned as an improvement over the wood huts many lived in before, poor construction at Vale’s resettlement site in Cateme and 25 de Setembro has led to cracks and leaks in many homes and widespread dissatisfaction with the overall quality of the houses. As mentioned earlier, at the time of writing, Vale was in the process of undertaking repairs to all the houses.

Resettled households in Cateme have had to live without adequate access to replacement agricultural land for three years due to delays in the government’s allocation of land. Households in Cateme and Mwaladzi experienced problems with erratic water supply for months after resettlement.[72] And households in Mwaladzi have had delayed access to the school and health clinic promised for their community. Many infrastructure improvements happened only after resettlement and after complaints from the community, such as the construction of an access road to connect Cateme to the main road or the drilling of additional bore wells in Cateme and Mwaladzi.

Other elements of the resettlement have gone well. All resettled households are receiving land use titles (DUATs) for their new household and agricultural plots, and these were provided in the names of both men and women. Few households had a DUAT before their move. Both Vale and Rio Tinto have made investments in education and training, most notably Vale’s construction of a secondary school in Cateme.

Vale paid for the construction of and equipment for Cateme’s residential secondary school. It is only the fourth secondary school in Tete province, has a computer lab, and accommodates 300 students from the region.[73] According to Vale, the Cateme hospital, also constructed by Vale, serves about 75 people a day.[74] All households have experienced an improvement in sanitation as the number of households with toilets increased from only a few prior to resettlement to 100 percent after the move.

As discussed in more detail in chapter V, local, provincial, and central government officials have acknowledged some problems—such as those linked to housing—publicly committing to prevent similar shortcomings in future resettlements. However, they have been slow to address the land and water problems highlighted below. The government’s limited capacity and experience with resettlement have exacerbated some problems.

Representatives from Vale and Rio Tinto have acknowledged some of the shortcomings in their resettlement processes and are exploring ways to address them. Their proposed solutions to the most serious problems linked to land quality, water supply, and ability to carry out secondary livelihoods (such as chicken-rearing) are long-term in nature. These have not been adequately complemented by measures to alleviate immediate needs and furthermore, not all affected households will benefit.

Interference with the Right to Food and a Reduction in Self-Sufficiency

Here when you have nothing, it means you really have nothing. There, when I needed money I could go to the bush to get wood or charcoal to sell.

—Flavia J., resettled farmer, Cateme, May 10, 2012

Many families resettled by Vale and Rio Tinto have experienced a deterioration of their livelihoods and independence, going from farmers able to produce food for much of the year to communities reliant on outside aid and food-for-work programs.[75]

Most of the individuals resettled to Cateme and Mwaladzi were farmers who supplemented their crops with cash income from selling charcoal, firewood, fruits, and vegetables in the nearby Moatize market.[76] As is typical across much of Mozambique, even households whose primary economic activities were waged jobs or a small business also generally had a machamba, a small plot of land, to produce part of their food.

Many of the resettled individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch were deeply frustrated by their loss of self-sufficiency. Malosa C., resettled by Rio Tinto to Mwaladzi in 2011 said, “We are suffering a lot. We had a meeting with the company and told them that if you can’t supply us with food and water, it is better that you take us back to the place where we used to live, and we will produce our own food and we will continue our life without depending on you.”[77]

Poor-Quality Farmland and Low Production

We used to produce enough food to keep in storage.... The [plot of] land here is bigger, the problem is the land is not good. It did not rain enough this year, but also, the land is not good. We grew beans, only beans. You can check our storage, there is nothing there.... All the food we are eating, we are buying.

—Elena M., a resettled woman, Mwaladzi, May 11, 2012

Many households’ food production dropped dramatically upon resettlement to Cateme and Mwaladzi due to aridity and poor productivity of the land. In their original homes in Chipanga, Benga, and Capanga, most households had agricultural plots for growing staples such as maize and sorghum and many had additional vegetable gardens near the naturally irrigated soil on the banks of the Zambezi or Revuboé rivers or other water sources close to their villages. Teresa J. said,

[Before the move] I had one big plot for farming and one small plot for vegetables. I could fill up my storage with maize. I produced about four or five bags of sorghum. We produced enough for ourselves ... sometimes we could sell [a surplus]. We never stayed a long time without food.[78]

Out of the 26 households to whom Human Rights Watch administered a detailed survey on farming practices in Cateme, 25 de Setembro, and Mwaladzi, twenty said that, prior to resettlement, they typically grew enough crops to last through the year.[79] Of these, only one household said they were food self-sufficient after resettlement. Community leaders, teachers, nurses, and NGO activists living or working in these two communities said these problems are common. Respondents in Cateme and Mwaladzi said their productivity fell due to the aridity and poor fertility of the soil.