A Poisonous Mix

Child Labor, Mercury, and Artisanal Gold Mining in Mali

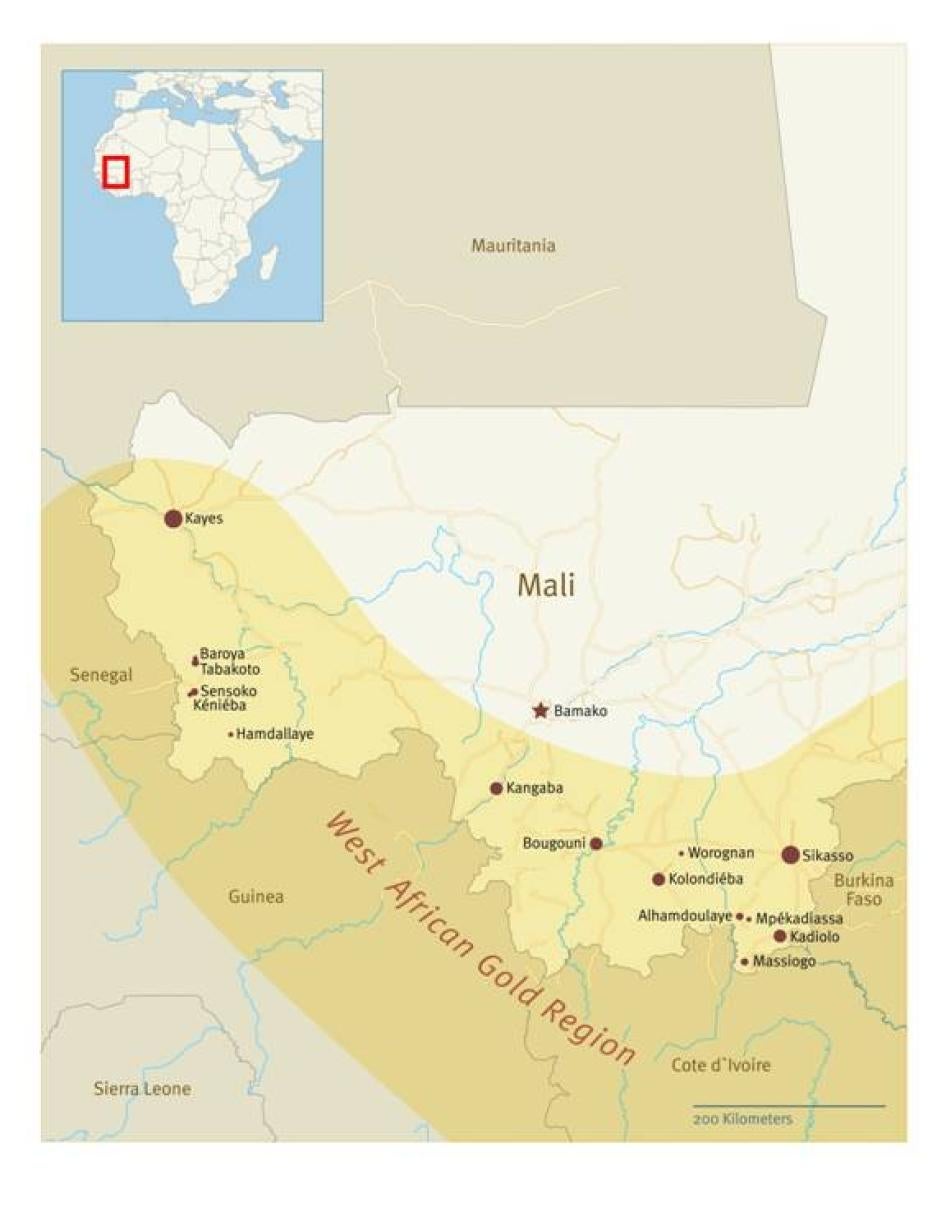

Regional Maps

Summary

In many poor rural areas around the world, men, women, and children work in artisanal gold mining to make a living. Artisanal or small-scale mining is mining through labor-intensive, low-tech methods, and belongs to the informal sector of the economy. It is estimated that about 12 percent of global gold production comes from artisanal mines.

Mining is one of the most hazardous work sectors in the world, yet child labor is common in artisanal mining. This report looks at the use of child labor in Mali’s artisanal gold mines, located in the large gold belt of West Africa. Mali is Africa’s third largest gold producer after South Africa and Ghana; gold is Mali’s most important export product.

It is estimated that between 20,000 and 40,000 children work in Mali’s artisanal gold mining sector. Many of them start working as young as six years old. These children are subjected to some of the worst forms of child labor, leading to injury, exposure to toxic chemicals, and even death. They dig shafts and work underground, pull up, carry and crush the ore, and pan it for gold. Many children suffer serious pain in their heads, necks, arms, or backs, and risk long-term spinal injury from carrying heavy weights and from enduring repetitive motion. Children have sustained injuries from falling rocks and sharp tools, and have fallen into shafts. In addition, they risk grave injury when working in unstable shafts, which sometimes collapse.

Child miners are also exposed to mercury, a highly toxic substance, when they mix gold with mercury and then burn the amalgam to separate out the gold. Mercury attacks the central nervous system and is particularly harmful to children. Child laborers risk mercury poisoning, which results in a range of neurological conditions, including tremors, coordination problems, vision impairment, headaches, memory loss, and concentration problems. The toxic effects of mercury are not immediately noticeable, but develop over time: it is hard to detect for people who are not medical experts. Most adult and child artisanal miners are unaware of the grave health risks connected with the use of mercury.

The majority of child laborers lives with and work alongside their parents who send their children into mining work to increase the family income. Most parents are artisanal miners themselves, and are paid little for the gold they mine, while traders and some local government officials make considerable profit from it. However, some children also live or work with other people—relatives, acquaintances, or strangers, and are economically exploited by them. A significant proportion of child laborers are migrants, coming from different parts of Mali or from neighboring countries, such as Burkina Faso and Guinea. Some of them may be victims of trafficking. Young girls in artisanal mining areas are also sometimes victims of sexual exploitation and abuse.

Many children working in artisanal mining never go to school, missing out on essential life skills as well as job options for the future. The government has largely failed to make education accessible and available for these children. School fees, lack of infrastructure, and poor quality of education deter many parents in mining areas from sending their children to school. Schools have also sometimes failed to enroll and integrate children who have migrated to mines. Nevertheless, some child laborers attend school but struggle to keep up, as they are working in the mines during holidays, weekends, and other spare time.

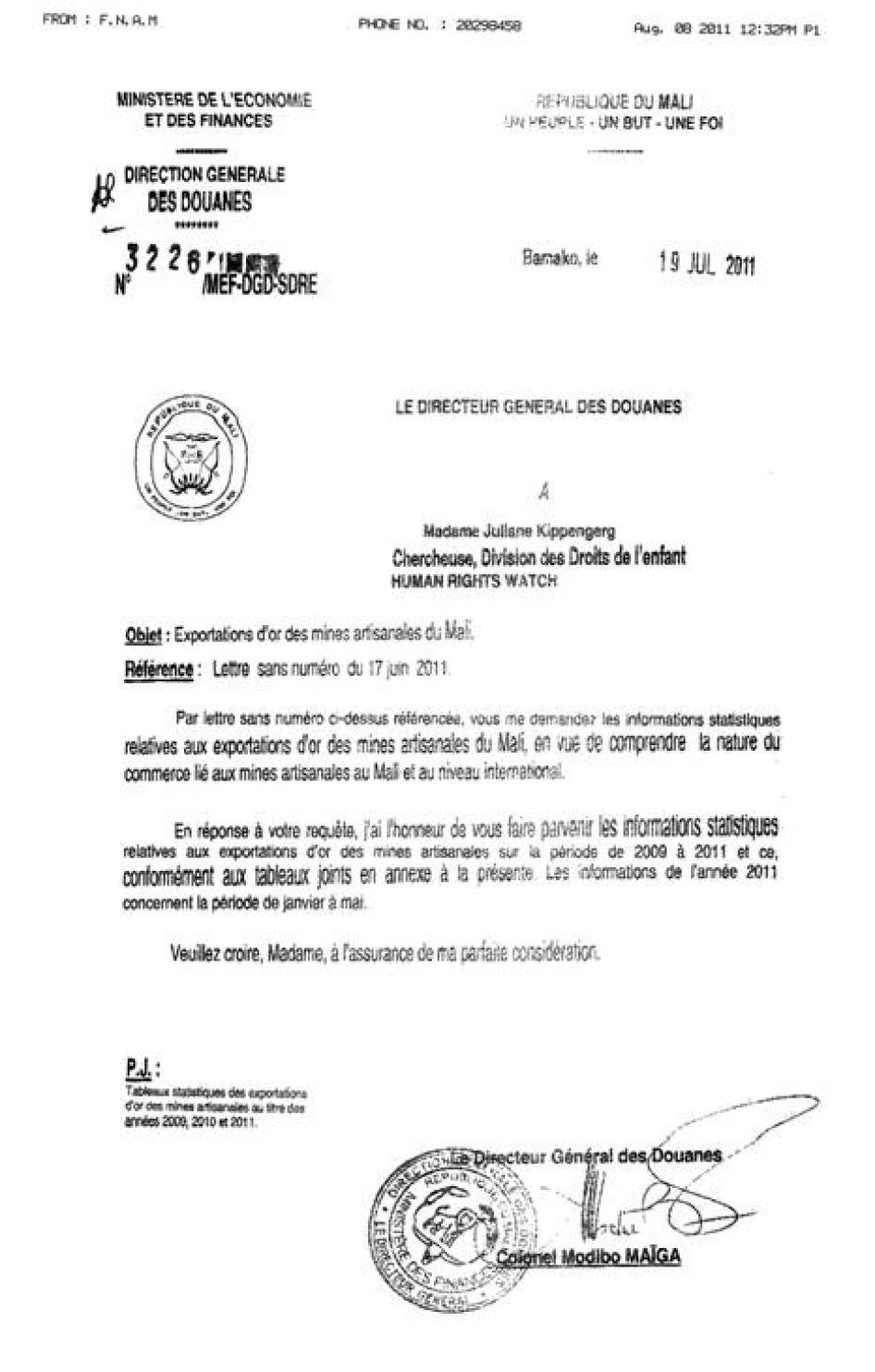

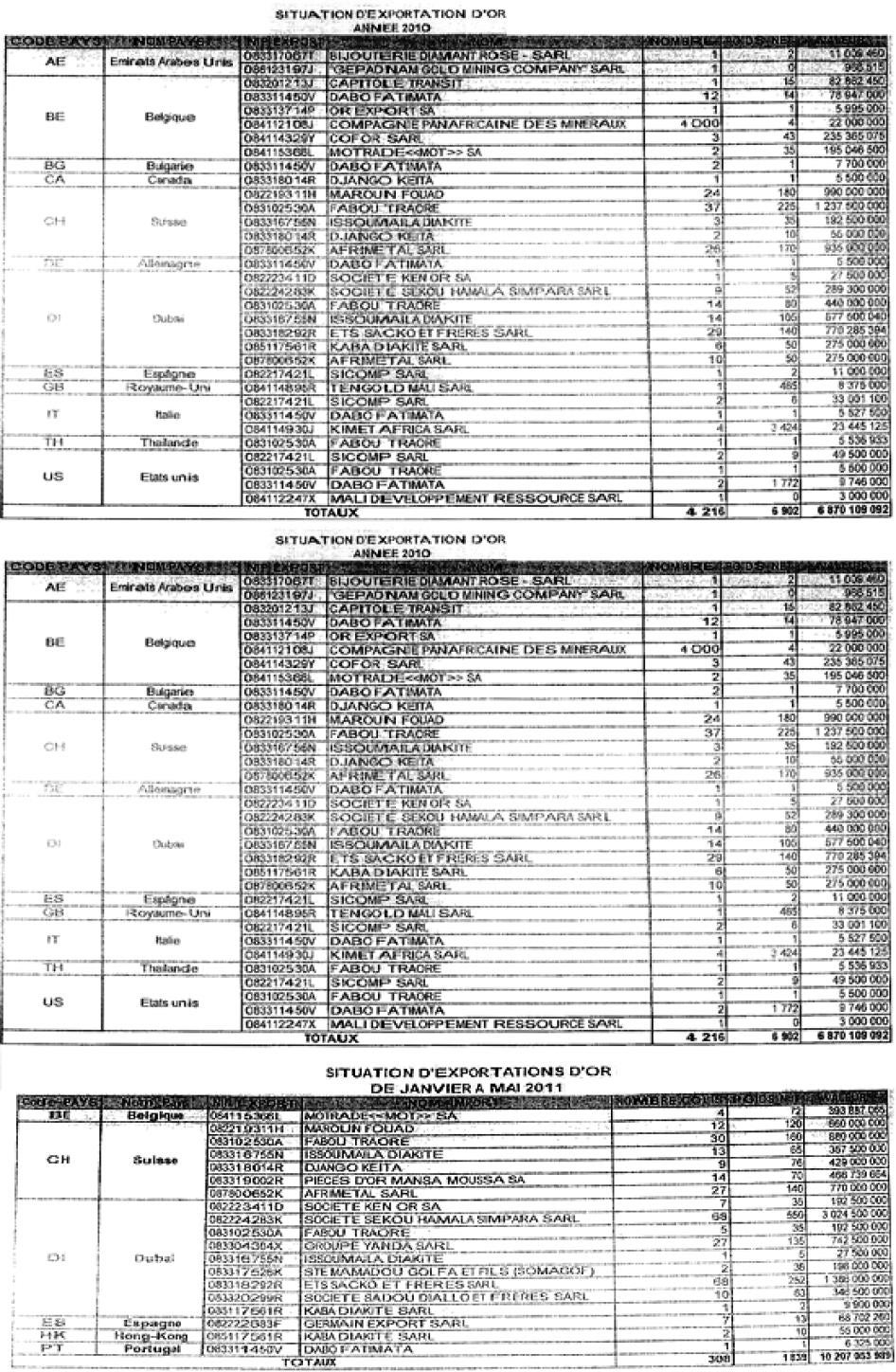

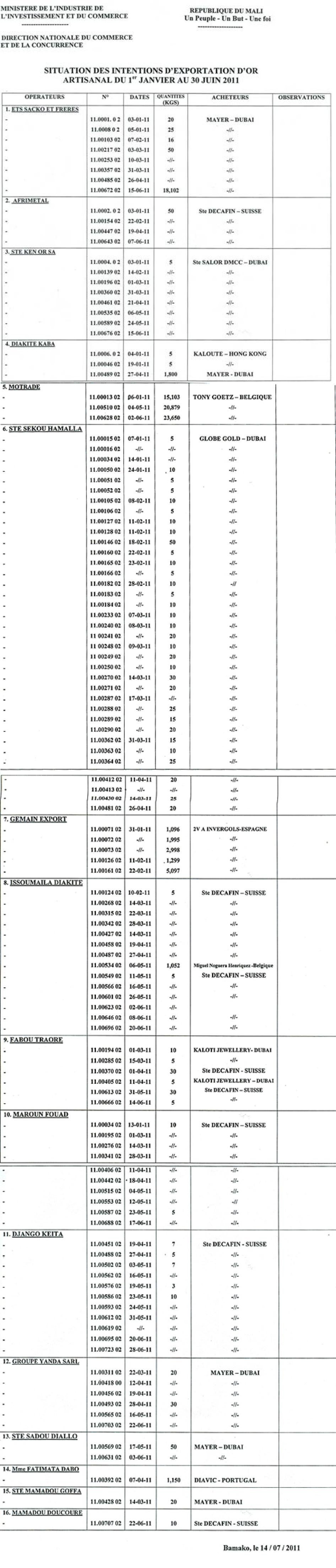

In the view of Human Rights Watch, with some exceptions, Malian and international gold companies operating in Mali have not done enough to address the issue of child labor in the supply chain. Much of the gold from Mali’s artisanal mines is bought by small traders who supply middlemen and trading houses in Bamako, the country’s capital. A few trading houses export the gold to Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates (in particular Dubai), Belgium, and other countries.

Under international law, the government of Mali is obligated to protect children from the worst forms of child labor, and from economic exploitation, trafficking, and abuse. It also has an obligation to ensure free and compulsory primary education for all. The government must take measures to avoid occupational accidents and diseases, and reduce the population’s exposure to harmful substances. International development partners should assist poorer nations, such as Mali, to fulfill their obligations under international law. Businesses, under international law and other norms, also have a responsibility to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for their impact on human rights through policies and due diligence measures.

Encouragingly, the government of Mali has taken some important measures to protect children’s rights. It has outlawed hazardous child labor in artisanal mines and, in June 2011, adopted a National Action Plan for the Elimination of Child Labor in Mali. The government has also made some progress in improving access to education, though net enrollment remains low at 60.6 percent. With regard to mercury, the government supports mercury reduction measures through the upcoming global treaty on mercury.

Yet, the government has not put its full political weight behind these efforts. Existing initiatives, such as the work of the National Unit to Combat Child Labor, tend to be isolated, understaffed, and lack full support from other ministries. Health policy lacks a strategy to prevent or treat health problems related to mercury use or other mining-related conditions. Child laborers, including those in artisanal mining areas, have not benefitted from government’s education policy, and the education system has not been adapted to their needs. Mining policy has focused on industrial mining, carried out by international companies, and has largely neglected problems related to artisanal mining, including child labor. Meanwhile, local government officials and traditional authorities such as local chiefs have benefitted financially from artisanal mining. Government policies on crucial areas such as health, education, and artisanal mining, are also sometimes undermined by the laissez-faire attitude of local government officials, who carry considerable weight in the current decentralized governance structure. Such attitude effectively undermines the government’s efforts to address child rights issues, including child labor in artisanal gold mining.

Donors, United Nations agencies, and civil society groups have undertaken some important initiatives on child labor, education, or artisanal mining in Mali. For example, the International Labor Organization (ILO) and a Malian non-governmental organization, Réseau d’Appui et de Conseils, have assisted children in leaving mining work and starting school. But such initiatives have been limited in scope, suffered from paucity of funding, and lacked consistent political backing. The United States and the European Commission have drastically reduced their funding for international child labor programs in Mali, contributing to a funding crisis at the ILO. At the international level, the ILO has failed to follow up on its 2005 call to action “Minors out of Mining,” in which 15 governments—including Mali—committed to eliminating child labor in their artisanal mining sector by 2015.

Hazardous child labor in Mali’s artisanal mines can only be ended if different actors—central and local governments, civil society, UN agencies, donors, artisanal miners, gold traders and companies—prioritize its elimination, give it their full political support, and provide financial support to efforts aimed at ending it. There is an urgent need for feasible and concrete solutions that can bring about change.

As a first step, the government should take immediate measures to end the use of mercury by children working in artisanal mining, through a public announcement reiterating the ban on such hazardous work for children, an information campaign in mining areas, and regular labor inspections.

Beyond this immediate step, the government and all relevant stakeholders should come together to implement the government’s action plan on child labor. The government should also take steps to improve access to education in mining zones, by abolishing all school fees, introducing state support for community schools, and establishing a social protection scheme for vulnerable children. The government and other actors should provide stronger support for artisanal gold miners, such as support in the creation of cooperatives, and the introduction of alternative technologies that reduce the use of mercury. The government should also address the health impact of mercury on artisanal miners, in particular on children, and address other mining-related health problems. International donors and UN agencies should support the government in its efforts to eliminate hazardous child labor in artisanal mining, politically, financially, and with technical expertise. There is the need to convene a national roundtable on hazardous child labor in artisanal mining in Mali, to bring together all relevant actors—government, civil society, UN, donors, experts, and business—and create momentum for concerted action.

Malian and international companies should recognize their responsibility regarding child labor and other human rights issues. Companies should introduce thorough due diligence processes and engage in meaningful dialogue with their suppliers and their government, urging measures towards the elimination of child labor within a specific time frame, for example, two years. They should also directly support projects that aim to eliminate child labor, such as education and health programs for children in artisanal mining areas. An immediate and total boycott of gold from Mali is not the answer to human rights violations in Mali’s artisanal gold mines. Boycott risks reducing the income of impoverished artisanal mining communities and may even increase child labor as families seek to boost their income.

At the regional level, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) should ensure that the future ECOWAS Mining Code prohibits child labor in artisanal mining, including the use of mercury, and mandates governments to take steps to reduce the use of mercury.At the international level, the future global treaty on mercury should oblige governments to take measures that end the practice of child laborers working with mercury. The ILO should build on its past efforts to end child labor in artisanal mining by reviving its “Minors out of Mining” initiative.

Key Recommendations

- The Malian government should immediately take steps to end the use of mercury by child laborers, through information dissemination and outreach with affected communities.

- The Malian government and international donors, including the United States and European donors, should give full political backing and sufficient financial support for the recently adopted National Action Plan on Child Labor, including to programs for the withdrawal of children working in mines.

- As part of a nationwide campaign on child labor and the right to education, local authorities—with oversight from national government—should raise awareness in the mining communities about the laws on hazardous child labor and compulsory education. Labor inspectors should start inspections in artisanal mines and sanction those who use child labor in contravention of the law.

- The Malian government should improve access to education for children in artisanal gold mining areas, by lifting school fees, introducing free school meals, increasing state financial support for community schools, and improving school infrastructure. It should also establish a social protection scheme for child laborers, including those in mining areas that ties cash transfers to regular school attendance.

- The Malian government, together with civil society groups, should develop a national action plan for the reduction of mercury in artisanal mining, with attention to the particular situation of children and pregnant women living and working in artisanal mining areas.

- The Malian government should develop a comprehensive public health strategy to tackle chronic mercury exposure and mercury poisoning in Mali, with a particular focus on child health.

- The Malian government should improve the livelihood of artisanal mining communities by providing training on improved mining techniques, assisting artisanal miners in efforts to set up cooperatives, and offering income-generating activities in other sectors.

- National and international companies buying gold from Mali’s artisanal mines should have due diligence procedures that include regular monitoring of child labor. If child labor is found, companies should urge the government and suppliers to take measurable steps towards the elimination of child labor in their supply chain within a defined time frame, and directly support measures to end child labor.

- The International Labor Organization should renew its “Minors out of Mining” initiative, in which 15 governments committed to eliminate child labor in artisanal mining by 2015.

- All governments should support a strong global treaty on mercury that requires governments to implement mandatory action plans for mercury reduction in artisanal gold mining. The action plans should include strategies to end the use of mercury by children and pregnant women working in mining, and public health strategies to address the health effects of mercury poisoning.

Methodology

Field research for this report was carried out between February and April 2011 in Bamako and in the mining areas in Western and S0uthern Mali. Human Rights Watch researchers visited three mining sites in Kéniéba circle, in the Kayes region of Western Mali — Baroya (Sitakili commune), Tabakoto (Sitakili commune), and Sensoko (Kéniéba commune) — and one mine in Worognan (Mena commune) in Kolondiéba circle, in the Sikasso region of Southern Mali (see map).

Human Rights Watch interviewed over 150 people—including 41 children working in mining areas (24 boys and 17 girls)—for this report.[1] Thirty-three of these children worked in gold mining, and the other eight, among them seven girls, worked as child laborers in other sectors such as childcare, domestic work, agriculture, or in small scale enterprises. Five of the forty-one children were immigrants; two were from Burkina Faso, and three were from Guinea. We also interviewed three young adults, ages eighteen and nineteen, two of whom were working in a gold mine, and one as a sex worker at a mining site.

While the majority of the children interviewed lived with their parents, five lived with relatives or other guardians, and seven were living on their own.

We also interviewed a wide range of other actors in mining areas, including parents and guardians of child workers, adult miners, teachers and principals, health workers and health experts, village chiefs, tombolomas (traditional mining chiefs), NGO activists, and sex workers. In addition, Human Rights Watch researchers held meetings with gold traders in mining areas and in Bamako, with representatives of UN agencies and donor governments. We interviewed the Minister of Labor and Civil Service and his staff, as well as officials in the Ministry of Mines, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Environment and Sanitation, the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of Promotion of Women, Child and Family Affairs. We also interviewed local government officials in Kéniéba and Kolondiéba circles.

We also interviewed international companies importing gold or other products through complex supply chains, including two companies importing gold from Mali’s artisanal mines. Outside Mali, we also interviewed several international experts on artisanal gold mining, mercury use, and health effects of mercury.

Interviews with child laborers were carried out in a quiet setting, without other adults present. The names of the interviewees were kept confidential. All names of children used in this report are pseudonyms. We arranged for a local NGO to intervene in the case of one child who was abused at home. When we interviewed children, we adapted the length and content of the interview to the age and maturity of the child. Interviews with children under the age of 10 did not last longer than 15 minutes, while those with older children took up to an hour.

Most interviews were conducted in Bambara through the help of an interpreter. Bambara is the mother tongue of about four million Malians of the Bambara ethnic group; it is also a lingua franca in Mali and several other West African countries. Three interviews with Guinean children and one with an 18-year-old from Guinea were conducted in French. One interview with an 18-year-old sex worker was conducted in English.

One challenge during this research was the assessment of the children’s age. Some children did not know their exact age. Parents or guardians were also sometimes unable to state the precise age of the child. In Mali, almost half of all births are not registered, making it difficult to obtain information on the real age of the children we interviewed.[2] We only considered interviewees as children when we were certain that they were children, judging their age by their own assessment, the assessment of relatives, and their physical appearance. Because of this, we did not include the statement of a boy who claimed he was 18, even though he looked younger.

In addition to interviews, we carried out desk research, consulting a wide array of written documents from government, UN, NGO, media, academic, company, and other sources.

I. The Context: Gold Mining in Mali

Mali’s Gold Economy

Gold has been mined for many centuries in Mali. Large West African kingdoms, including the Mali Empire (approximately 1235-1400), built their wealth on gold from the Bambouk region of Western Mali and the Trans-Saharan gold trade.[3] Gold has remained a central commodity during colonialism and in Mali’s postcolonial economy.

Since 1999, gold has been Mali’s number one export commodity, followed by cotton. In 2008, gold accounted for about 75 percent of all Malian exports.[4] While gold prices have dramatically increased over the last decade, prices for other commodities, such as cotton, have fallen. Mali is currently the third largest gold producer on the African continent, after South Africa and Ghana, and the thirteenth largest gold producer in the world.[5] Since 2005, Mali’s gold production has been around 50 tons per year—worth more than US $2.9 billion at September 2011 prices.[6]

The main gold mining regions lie in Western and Southern Mali, specifically in the Kéniéba area on the Senegalese-Malian border (historically known as Bambouk); the area around Kangaba less than 100 kilometers southwest of the capital; and in several areas in the Sikasso region (see map). While mining in Kéniéba and Kangaba dates hundreds of years back, many mines in the Sikasso region have been opened in recent years. The gold belt in the Sahel zone includes several other countries, such as Guinea, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Niger, and Nigeria.

Historically, Malian miners have practiced artisanal mining, known as orpaillage in French. Today, the practice still exists. Artisanal or small-scale mining is carried out by individuals, groups, families, or cooperatives with minimal or no mechanization, using labor-intensive excavation and processing methods. Artisanal miners (orpailleurs) operate with limited capital investment, often in the informal sector of the economy, and are not employed by a large company.[7] Mali’s artisanal mines produce an estimated four tons of gold per year, according to official records; the real number might be higher, though.[8] Due to rising gold prices, artisanal mining has attracted increasing numbers of people in Mali and the West African region over the last decade.[9]

The majority of gold produced today comes from large industrial mines. Among the important multinational companies in Mali are Anglo Gold Ashanti, Randgold (both South African multinational companies), IAMGOLD, Avion Gold (two Canadian corporations), Resolute Mining (from Australia), and Avnel Gold Mining (from the United Kingdom). These companies operate several large industrial mines, such as the Morila, Sadiola, Yatela, and Loulo mines, in joint ventures with the Malian government; the government holds a minority stake of about 20 percent.[10] A new mining law is currently underway; it will increase the government share in industrial mines, and oblige mining companies to implement local development projects.[11]

Despite its wealth in gold, Mali remains a very poor country. The 2010 Human Development Index, which measures health, education and income, ranks Mali as 160th out of 169 countries.[12] About 50 percent of the population is living on less than one dollar per day,[13] and social indicators are very low. Almost 20 percent of all children die before their fifth birthday, and adults have, on average, attended school for only 1.4 years.[14] Human rights and development organizations have commented critically on the limited benefit of Mali’s gold sector for the wider population, including a lack of revenue transparency.[15]

Artisanal Gold Mining

There are over 350 artisanal mining sites across Western and Southern Mali; their precise number is unknown even to the government.[16]

Estimates put the number of artisanal gold miners in Mali between 100,000 and 200,000.[17]Around 20 percent of artisanal gold miners are children.[18] Based on these estimates, the number of child laborers in Mali’s artisanal mines is between 20,000 and 40,000.

The work process is organized by groups of artisanal miners who agree at the outset how they will divide the gold mined. Groups may consist of adults and children. Artisanal mines have attracted workers from many parts of Mali, as well as from other countries in the West African subregion, such as Guinea and Burkina Faso.

Under the Mining Code, artisanal mining is legal in specified geographical areas called artisanal gold mining corridors (couloirs d’orpaillage).[19] In reality, most artisanal mining sites lie outside these corridors.[20]

The government usually tolerates these activities, in part because mayors and other local authorities, as well as traditional authorities, sometimes benefit financially from the presence of artisanal mines. In the context of decentralization during the 1990s, oversight over and taxing of artisanal mining has been relegated to the local authorities.[21] Sometimes, artisanal miners have to pay money or part of their gold to traditional authorities who have customary ownership over the land. According to customary practices that are still relevant today, traditional authorities—such as village chiefs—are considered the owners of all land belonging to a particular area.[22] They have the authority to open or close a mine. On behalf of the village chief, the tomboloma (traditional mining chief) deals with management issues at the mine. He assigns each group of miners a shaft and, in some areas, receives a payment for it.[23]He also manages conflicts among miners.

Mayors also sometimes charge for shafts or get other revenue from the mine.[24] A mayor in Kolondiéba circle moved his office from the regular town hall in the commune’s central town to a mining site when the mine was opened during 2010, and was receiving one third of each payment for each newly assigned shaft when we visited. His tomboloma explained:

The task of the tomboloma is to organize the space, set boundaries for each shaft, and guarantee security of the site. When I allow a miner, or a group of miners, to work there, I get money, and so do the mayor and the chef de village. Depending on the quality of the ore, the miner has to pay between 10,000 and 12,500 CFA francs (approximately between US $20.73 and US$25.91). One third of this amount goes to the tomboloma, one third goes to the mayor, and one third to the chef de village.[25]

In addition, miners frequently pay part of their earnings to more wealthy and powerful gold miners who rent out machines and equipment miners cannot afford to buy themselves. Such gold miners are persons of status and influence in the community, most commonly traditional authorities (or ‘notables’) or local government officials. For example, one mayor told Human Rights Watch that he “owned” a mine where he was renting out machines.[26] His advisor had 70 to 80 people working for him on eight sites.[27] The relationship between the wealthy gold miners and the ordinary artisanal miners sometimes resembles a relationship between an employer and an employee. Some wealthy gold miners also lend money to poorer miners, creating a burden of debt.Community leaders at one mining site described how the debt creates severe pressure on the artisanal miners, who try to pay the money back within a month, and they cited this as one of the reasons why parents send their children to work in the mines.[28]

Artisanal miners who have been assigned a particular shaft sometimes hire others to work for them. They are considered “owners” of the shaft. Several artisanal miners in the Kéniéba region explained that they had to give two out of three bags of ore to the “owner” of the shaft.[29]

In some areas, miners have set up cooperatives or economic interest groups to invest together in equipment, improve efficiency of the work process, and increase income.[30]

Child Labor and Migration in West Africa

Child labor is very common in Mali and other parts of West Africa. In the context of poverty, child labor is a common strategy to increase household income. Mali’s official figures state that about two-thirds of children in Mali work, and about 40 percent of all children between the ages of five and fourteen perform hazardous labor. In absolute figures, an estimated 2.4 million children are doing work that is considered harmful.[31] Child labor puts children at a disadvantage in accessing an education and the wider labor market, and exposes children to a range of human rights abuses, including labor exploitation, violence, and trafficking.[32]

The majority of children in Mali work in agriculture. Other sectors include domestic work—almost entirely performed by girls— husbandry, fishery, handicraft, commerce, and artisanal mining, including artisanal gold mining and quarrying. Another form of child labor is the forced begging by pupilsof Quranic schools (talibés) who are exploited by their teachers.[33]

There is a long history of child migration in West Africa.[34] Younger children are often sent to live with relatives, a practice called confiage (child fostering).[35] For adolescents—older children under the age of 18—leaving the village and seeking economic independence have been an important rite of passage in the past and present.[36]

While child fostering and migration can benefit a child’s access to education and upbringing, it can also lead to exploitation and trafficking.[37] Trafficking of children into various work sectors has increasingly become a problem in West Africa, including Mali. Most of the trafficking is done through small, informal networks, including families and acquaintances. In addition to internal trafficking, there is cross-border trafficking between Mali and its neighboring countries.[38]

II. The Legal Framework

International Human Rights Law

Mali has ratified a great number of international treaties, including the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and its Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography,and the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children.[39] Furthermore, Mali has ratified binding ILO Conventions, in particular the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention (Convention 182) and the Minimum Age Convention (Convention 138).[40] At the regional level, Mali is a state party to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.[41] In Mali, international treaties have primacy over national legislation.[42]

Child Labor

Child labor is defined by the ILO as work that is “mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful to children” and “interferes with their schooling.”[43] International law does not prohibit all types of work for children. Certain types of activities are permitted when they do not interfere with the child’s schooling and do not harm the child.[44] The Minimum Age Convention and Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention spell out in detail what types of work amount to child labor, depending on the child’s age, the type and hours of work performed, the impact on education, and other factors.

According to the CRC, all children have the right to be protected from economic exploitation.[45] Economic exploitation refers to situations where children are taken advantage of for the purpose of material interests, including through child labor, sexual exploitation, and trafficking.[46]

The Worst Forms of Child Labor

The Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention defines the worst forms of child labor as “all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children … and forced or compulsory labor”, as well as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.”[47] The latter type of work is also defined as hazardous work.

According to the ILO, mining counts among the most hazardous sectors and occupations.[48] Under the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, hazardous work includes work that exposes children to abuse, work underground, work with dangerous machinery, equipment, and tools, work that involves the manual handling or transport of heavy loads, work in an unhealthy environment that exposes children to hazardous substances, agents, or processes, or to temperatures damaging to their health, and work under particularly difficult conditions such as working long hours.[49] The Convention calls upon states to define hazardous occupation in national legislation.[50]

Minimum Age

For work other than the worst forms of child labor, international law requires states to set a minimum age for admission into employment and work. The Minimum Age Convention states that “the minimum age shall not be less than the age of compulsory schooling and, in any case, shall not be less than 15 years.”[51] As an exception, developing countries are allowed to specify a lower minimum age at 14 years at the moment of ratification.[52]

The Minimum Age Convention also permits light work from the age of 13. Light work is defined as work “which is not likely to be harmful to their health and development; and not such as to prejudice their attendance at school, their participation in vocational orientation or training programs […] or their capacity to benefit from the instruction received.”[53]

The Right to Education

Both the CRC and the ICESCR lay down the principle of free and compulsory primary education.[54] In addition, higher education, including secondary schooling as well as vocational training, should be made available and accessible to all.[55] States are required to protect children from work that interferes with their education.[56]

While the rights under the ICESCR are subject to progressive realization, states have a “minimum core obligation to ensure the satisfaction of, at the very least, minimum essential levels of each of the rights.” These are not subject to progressive realization but have to be fulfilled immediately.[57] In particular, states have to “provide primary education for all, on a non-discriminatory basis.[58] They also have to ensure that primary education is free of charge and compulsory. To realize the right to primary education, states have to develop and implement plans of action; where a State party is clearly lacking in financial resources, the international community has an obligation to assist.[59]

The CRC urges states to implement measures, where necessary, within the framework of international cooperation.[60] Similarly, the African Charter on the Rights and the Welfare of the Child provides that “every child has the right to an education” and stipulates that free and compulsory basic education should be achieved progressively.[61]

The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health

The right to the highest attainable standard of health is enshrined in international human rights law. The ICESCR, the CRC, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the African Charter on the Rights and the Welfare of the Child recognize the right to physical and mental health as well as the right of access to health care services for the sick.[62] Several international and regional legal instruments also require states to protect children from work that is harmful to their health or physical development.[63]

With regards to hazardous work environments, state parties to the ICESCR have the obligation to improve “all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene,” for example, through preventive measures to avoid occupational accidents and diseases, and the prevention and reduction of the population’s exposure to harmful substances such as harmful chemicals.[64]

The full realization of the right to the highest attainable standard of health has to be achieved progressively.[65] In addition, states face core obligations that have to be met immediately, including essential primary health care, access to health services on a non-discriminatory basis, and access to an adequate supply of safe and potable water.[66] Obligations of comparable priority include the provision of reproductive, maternal, and child health care, and of education and access to information concerning the main health problems in the community.[67]

Protection against Violence, Sexual Abuse, and Trafficking

The CRC and other international treaties to which Mali is a party protect children from violence and abuse. Although parents or legal guardians have the primary responsibility for children in their care, states have an immediate obligation to protect children from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury and abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment, or exploitation, including sexual abuse.[68] Sexual exploitation and abuse of children is prohibited in all forms.[69]

Trafficking in persons is prohibited under international law.[70] Having a slightly broader scope than trafficking in adults, trafficking in children is defined as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation.”[71] Exploitation includes “at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude, or the removal of organs.”[72] Trafficking of children is also classified as a worst form of child labor.[73]

International Human Rights Obligations of Businesses

Although governments have the primary responsibility for promoting and ensuring respect for human rights, private entities such as companies have human rights responsibilities as well. This basic principle has achieved wide international recognition and is reflected in international norms, most recently with the adoption of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights by the UN Human Rights Council in June 2011.[74]

The Guiding Principles were elaborated by John Ruggie, former United Nations’ special representative of the secretary general on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. The Principles lack guidance with regards to government regulation of companies’ human rights impacts and have failed to call for mandatory monitoring and reporting of companies’ human rights impacts. Nonetheless, they serve as a useful guide to many of the human rights obligations of businesses and of the governments that oversee their activities. The Principles place particular emphasis on the concept of human rights due diligence—the idea that companies must have a process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for their impact on human rights. According to the Guiding Principles, corporations should monitor their impact on an ongoing basis and have processes in place that enable the remediation of adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute.[75]

Businesses can also choose to join the UN Global Compact, a voluntary initiative which incorporates human rights commitments. The 10 principles of the Global Compact cover general human rights, labor rights, and environmental and anti-corruption standards that are derived from the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and other texts. Businesses committing to this voluntary corporate responsibility initiative agree to “uphold the effective abolition of child labor.”[76]

In May 2011 the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) adopted a Recommendation of the Council on Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas.[77] The Recommendation is not legally enforceable, but calls upon member states and others to implement a due diligence framework in the mineral supply chain, and a model supply chain policy. The model policy states, “We will neither tolerate nor by any means profit from, contribute to, assist with or facilitate the commission by any party of… any forms of forced or compulsory labor … [and] the worst forms of child labour[.]”[78] The OECD is now in the process of developing supplements relating to specific minerals, including a supplement on the gold supply chain.[79]

National Laws on Human Rights

Under the 1992 Malian labor law, children are allowed to work from the age of 14, in violation of international law, which sets the age at 15.[80] Malian law prohibits forced, compulsory, and hazardous labor, or work that exceeds children’s forces or may harm their morals, for anyone under age 18.[81]

The government has drawn up a national list of hazardous work for children, which prohibits the use of children in many forms of labor in traditional gold mining. Specifically, it prohibits digging of shafts, cutting and carrying of wood for underground shafts, transport of rock from the shaft, crushing, grinding, panning in water, and the use of explosives, mercury, and cyanide.[82] A decree also stipulates how much weight children are allowed to carry, according to their age, gender, and mode of transport.[83]

Mercury is not prohibited in Mali, but it is listed in the government’s list of dangerous waste, subjecting it to strict rules for trade.[84]

According to the law on education, education is free (gratuit) in Mali; this means that any school fees are illegal.[85] The same law also stipulates that education is compulsory; parents have an obligation to place their children in school during a nine-year period of basic education (enseignement fondamental), starting at age six.[86]

The Penal Code contains protections against violence, child neglect, and child trafficking.[87] Child trafficking is defined as displacement of a child in conditions that are exploitative and turn the child into a commodity.[88] A new initiative for a separate anti-trafficking law is currently underway.[89]

The Child Protection Code spells out key protections for children, such as the right to be treated equally and the right to be free from violence, neglect, sexual abuse, and exploitation.[90] The Code specifically bans economic exploitation, including trafficking or child labor that harms the child’s education, health, morals, or development. It puts the minimum age for child labor at 15.[91]

III. Hazardous Child Labor in Mali’s Artisanal Gold Mines

I work at the mining site. I look after the other children and I carry minerals. It is hard. Sometimes my arms hurt from it.… Once I had an accident. I injured my finger. I wanted to carry a rock and it fell on my foot. I was taken to the health center. This happened about two months ago.… I work with mercury. You mix it in a cup and put it on the fire. I do this at the site.… I would like to leave this work.

—Mamadou S., estimated age six, Baroya, Kayes region, April 3, 2011

It's my stepmother who makes me work there. I don't want to. My real mother left. My stepmother takes all the money they pay me…. I don't get any money from the work…. Our work starts at 8 a.m. and continues the whole day…. I take the minerals [ore] and pan them. I work with mercury, and touch it. The mercury I was given by a trader…. He said mercury was a poison and we shouldn't swallow it, but he didn't say anything else about the mercury…. I don't want to work in the mines. I want to stay in school. I got malaria, and I am very tired when I work there [at the mine].

—Mariam D., estimated age 11, Worognan, Sikasso region, April 8, 2011

It is estimated that between 20,000 and 40,000 children work in Mali’s artisanal gold mines.[92] Girls and boys are both active in artisanal gold mining, in roughly equal numbers.[93] They work under conditions that result in short-term and long-term health problems and bar them from getting an education. Their right to health, to education, and to protection from child labor and abuse is violated on a daily basis.

Children are sent into child labor to increase the family income. Many parents of child laborers are artisanal miners, and they often earn very little. Artisanal miners frequently have to pay money or part of their ore or gold to traditional or local authorities, or to miners who out rent machines or hire them as their workforce. Some artisanal miners are also in debt, putting pressure on them to send their children to work in the mines, in order to boost family income.

Most children go with a parent or sibling to the mine, and work alongside them. Others, however, are sent to live and work with another family, following a tradition of child fostering, or live and work by themselves. Other adults, such as relatives or even strangers, sometimes also take advantage of the vulnerability of children, and economically exploit them by sending them to work in the mines without pay.

The government has failed to effectively address child labor in artisanal mining. It has not enforced current law banning hazardous forms of child labor, and has done too little to make education available and accessible in artisanal mining areas. The government has also failed to address child protection issues, mining-related health problems, and environmental health issues related to mercury in artisanal mining.

Hazardous Child Labor throughout the Mining Process

Digging Shafts and Working Underground

Digging and constructing shafts or pits is the first phase of the gold mining process, and is physically demanding. Boys as young as six do this work. One boy, about six years of age, complained that digging shafts caused him pain in the palms of his hands.[94] Another boy, Moussa S., also about six years old, told Human Rights Watch:

I dig shafts, with a pickaxe. It is really difficult. I have pain sometimes, for example headaches.[95]

Hamidou S., estimated to be eight years old, told us that he also dug shafts with a pickaxe, resulting in back and neck pain.[96]

Shafts are estimated to be at least 30 meters deep, and sometimes more.[97] Those who climb into shafts and work underground are considered doing “man’s work”, even though some are also children. Oumar K., about 14, described his experience:

I climb into shafts, something like 30 meters deep. I started this year. Before that, I worked in mining too for about three years – pulling the rope [with a bucket out of the shaft]. The work with the bucket was very tiring.... The shaft is worse…. When you are in the shaft, you are alone and do all the work…. This year, a shaft collapsed, but no one died. It had rained a lot and one part of the shaft slipped and came down. It collapsed on two people. We dug other shafts to get them out. They had back pains but no other injuries.[98]

There are very few security precautions to ensure that shafts are stable or that those underground can get up safely. Oumar K. explained that he took turns with another person once every hour to ensure that the person underground still had enough strength to climb up.[99]

Some miners perform magic rituals that they believe will protect them from accidents. The boys working underground put on a brave face, but barely manage to conceal their fear and frustration. Ibrahim K., who migrated from neighboring Guinea to Mali to work in artisanal mines, said:

I am 15 but I work as a man. I work in a team of 10 people. I climb up and down the shaft and work in the shaft. If you say you are tired, they pull you out and you rest. The big men don't mind. Some only work two hours, I work all day….

It's dangerous—there are often collapses. People are injured. Three died in a cave-in. The little children don't come down into the hole. What they do about safety is that the big men bring sacrifices [such as] butter, lamb, chicken…. I have had problems since working there—my back hurts and I have problems urinating. No one says anything to me about safety….

I don't like working here. I would do anything to go back to Guinea. But I can't save any money. There is a lot of suffering; it's very hard here because of not having enough money.[100]

“Pulling the Rope” and Transporting Ore

Outside the shaft, children and adults pull up the ore with buckets. This task is commonly called tirer la corde (“pulling the rope”). Several children told us that pulling and transporting the ore caused them pain and that they wanted to stop this work. Karim S., a boy who worked at Worognan mining site with his older brother, told us about his pain:

I pull the buckets up…. It hurts in the arms and back. When it hurts I take a break.... I once took some traditional medicine for the pain in my arms, but it did not really help.[101]

Lansana K., a 13 -year-old boy who digs shafts and pulls up heavy buckets, complained:

It is really difficult. It can make you sick.... I have already had headaches.… I also sometimes have back pain, shoulder pain, and muscle pain generally.[102]

Once the ore has been pulled out of the shaft, it has to be transported to places where it is bagged for storage or crushed, ground, and panned. Most workers—adults and children—carry the ore on their shoulders, while some others use small carts to transport the load. Several boys interviewed complained about pain from transporting ore. One of them was 15-year-old Djibril C., who said:

It's very difficult—it’s very heavy. I carry it [the ore] on my shoulders and head all day long. Sometimes I take a break to eat. I have had pain in my shoulders and chest since I started working there [two months ago].[103]

Another boy, who was 14 years old, told us that he transported the ore from the shaft to the place where it is put into sacks. Although he used a cart with a donkey for this, he said he often felt stiff from lifting weight and being bent over, concluding: “I feel that the work is too much for me.”[104]

Some children also carry heavy loads of water in the mines, mostly for use in gold panning (and sometimes for drinking). This is mostly done by girls and poses the same health problems as other transport work.[105]

Crushing Ore

Hard and rocky ore must be crushed and ground before it can be panned for gold. When crushing machines and mills for grinding are available, miners rent them to break and grind up the earth.[106] The machines are loud and produce a lot of fumes. Men and adolescent boys usually operate the machines, and they often spend many hours a day at crushing machines or mills without any protective gear.[107]

When there are no machines to crush the rock, artisanal miners pound it manually, usually with a hammer or a pestle and mortar. This work is sometimes carried out by girls or boys.[108] It can lead to accidents, as well as short-term and long-term back injury.

Panning

Once the ore has been ground to a fine sandy quality, it is washed (or panned) for gold. Gold panning is the basic technique to recover gold from ore. The circular shaking of ore and water in a pan causes the gold to settle to the bottom of the pan, while the lighter material can be washed off the top. This work is largely considered women’s and girls’ work.[109] Of the 10 girl miners we interviewed, nine said that they panned for gold. Some boys pan for gold, too.[110]

Several girls mentioned back pains, headaches, and general fatigue caused by gold panning.[111] Eleven-year-old Susanne D. said:

My back sometimes aches because I am bending down. I have never been to a health center [to treat this], but I take tablets sometimes. When I tell my mother that it hurts, she tells me to take a break.[112]

Aminata C., a 13-year-old girl from Baroya mine, told us:

I do gold panning and mixing [amalgamation]. I often feel pain everywhere, I have headaches and stomach aches. When I tell my dad about the pain, he gives me paracetamol.[113]

Sometimes, prior to panning, the ore is further concentrated into a gold-rich material through sluices. Sluices are inclined troughs that are lined in the bottom with a carpet or other material that captures gold particles.[114] Children also do this work.

“I Work with Mercury Every Day”: The Use of Mercury for Amalgamation

Artisanal gold miners in Mali and all over the world use mercury—a white-silvery liquid metal—to extract gold from ore, because it is inexpensive and easy to use.[115] In Mali, amalgamation is often carried out by women and children (girls and boys).[116] Mercury is mixed into the ground-up, sandy ore and binds to the gold, creating an amalgam. After the amalgam has been recuperated from the sandy material, it is heated to evaporate the mercury, leaving gold behind.

The use of mercury in Mali’s artisanal mining sites put child laborers at grave risk of mercury poisoning, primarily through mercury vapor. Mercury is a toxic substance that attacks the central nervous system and is particularly harmful to children.[117]

Of the 33 children interviewed working in artisanal mining, 14 said they were themselves carrying out amalgamation. The youngest was six years old.[118] Susanne D., 11, told us how she works with mercury:

Once the ore is panned, you put a bit of mercury in. You rub the ore and the mercury with your two hands. Then, when the mercury has attracted the gold, you put it on a metal box and burn it. When I have finished, I sell the gold to a trader. I do this daily. I usually get about 500 CFA francs (equivalent of US$ 1.08) for the gold… I know mercury is dangerous, but I don’t know [understand] how. I do not protect myself. On some days I do the amalgamation with my mother, on others by myself.[119]

None of the children we spoke with knew why mercury is dangerous or how to protect themselves. Some had never heard at all that there is any health risk associated with the use of mercury. Fatimata N., a girl from Burkina Faso, told us:

I started gold mining at a small age. I pan for gold, I also work with mercury. I put the mercury in with the sand and the water. I mix it with my bare hands. Then I put the mercury in my pagne [a wrap-around skirt she wears]. The mercury that I squeeze out, I keep it in a small plastic bag. I also burn it. I have never heard that this is unhealthy. I work with mercury every day.[120]

Some artisanal miners consider mercury a powerful, magic substance. Mohamed S., 16, who carries out amalgamation, explained:

No one has ever told me that mercury is dangerous. We are told that it has magic powers… to capture the gold out of minerals. We work without any protection here…. This work exhausts me and often makes me sick—I have stomachaches, malaria, and cough. When I tell my father about these sicknesses, he gives me extracts from traditional plants.[121]

Although mercury is a dangerous product under Malian government regulations, the mercury trade is flourishing. Frequently gold traders also deal in mercury. Traders told us that they receive mercury from countries in the subregion, notably Ghana and Burkina Faso.[122] Mercury traders are present in gold mining areas and sell mercury on site. Human Rights Watch learned of one town where mercury was even sold in a shop that had about 25 kilograms of mercury in stock.[123] In some areas, traders provide mercury for free to the miners, so miners will sell the gold to them.

Mercury traders provide mercury directly to children. Mariam D. in Worognan said:

I work with mercury and touch it. The mercury, I was given by a trader…. He said mercury was a poison and we shouldn't swallow it, but he didn't say anything else... I am very tired when I work there [at the mine].[124]

Another boy told us that he received mercury from the local trader. Oumar K. said he mixes mercury and the sandy ore and then takes the amalgam back to the trader, who burns it while Oumar K. watches. Asked about health risks, he said that he did not know that mercury is dangerous.[125]

Mercury Poisoning of Children in Artisanal Mines—an “Invisible Epidemic”

Mercury, a toxic substance that attacks the central nervous system, is particularly harmful to children. It can cause, among other things, developmental problems. There is no known safe level of exposure.[126] Mercury can also attack the cardiovascular system, the kidneys, the gastrointestinal tract, the immune system, and the lungs. Symptoms of exposure to mercury include tremors, twitching, vision impairment, headaches, and memory and concentration loss. Higher levels of mercury exposure may result in kidney failure, respiratory failure, and even death. The chemical can also affect women's reproductive health, for example by reducing fertility and leading to miscarriages.[127] Most people are exposed to dangerous levels of mercury either through inhalation of mercury vapor or through the consumption of mercury-contaminated fish.[128]

Artisanal miners, including child laborers, are exposed to mercury through the inhalation of vapors that develop when the amalgam is smelted. They are also exposed to mercury through skin contact, though the health risk is less severe compared to inhalation of mercury vapor. [129] Researchers have described mercury intoxication an “invisible epidemic.”[130]

Although there are no studies on Malian children, a study on mercury exposure of children in artisanal gold mines in Indonesia and Zimbabwe found that children living in the mines had significantly higher levels of mercury in their blood, hair, and urine than those living elsewhere.[131] Child laborers—those living in the mining area and working with mercury—had the highest level of mercury concentration in blood, hair, and urine. They also showed symptoms of mercury intoxication, such as coordination problems (ataxia), tremors, and memory problems. The main cause for this was the exposure to mercury vapors when burning the amalgam to recover the gold.[132]

Mercury is particularly harmful to unborn babies and infants, and can be transmitted in utero and through breast milk. It is therefore of concern that women miners work with mercury when they are pregnant or breastfeeding.[133] In addition, small children inhale the mercury vapor when they are present near amalgamation sites, either at the mine or in the home. During one visit, we observed a woman with a baby on her lap assisting another woman with amalgamation by holding the mercury in her hands.[134]

Children are also exposed to mercury through contaminated waters and the consumption of fish that live in them.[135] Women miners in Sensoko told us that they regularly empty the water used for amalgamation into the river.[136]This is dangerous because in water, mercury may convert into its most toxic form, methylmercury, which accumulates in fish and reaches the population through fish consumption.[137]In Worognan, Human Rights Watch researchers observed how artisanal miners empty water on the ground, right next to houses, after being used for amalgamation. A local gold trader confirmed that it was a common practice to empty water on the ground in residential areas.[138]

|

The Use of Mercury in Artisanal Mining: A Global Toxic Threat Mercury is used by artisanal miners in at least 70 countries around the world including countries across the Sahel gold belt. There are 13 to 15 million artisanal miners working worldwide who risk being directly exposed to mercury; many of them are women and children.[139] The chemical is affecting the environmental health of many more people globally. An estimated 1,000 tonnes of mercury are released from artisanal miners each year—around 400 tonnes go into the atmosphere, and around 600 tonnes are discharged into rivers, lakes, and soil. China, Indonesia, and Colombia are among the countries with the highest estimated emissions.[140] Mercury is the cheapest and easiest gold extraction method. Mercury-free gold extraction methods require more capital, training, and organization than many artisanal miners have access to. Industrial mines have phased out the use of mercury and switched to cyanide processing, which poses another set of serious health risks. Occasionally cyanide has been promoted as an alternative to mercury for artisanal miners, and resulted in the parallel use of both mercury and cyanide. This is particularly dangerous, as cyanide can exacerbate mercury’s negative impacts on the environment. In the absence of a safe and practicable mercury-free alternative, several methods are being promoted by the UN and NGOs to reduce the use of and exposure to mercury, such as emission-reducing technology (small containers that retain mercury vapor, known as retorts, or fume hoods), recycling mercury, and methods to concentrate the gold before amalgamation.[141] In recognition of the global threat posed by mercury, a global treaty for the reduction of mercury is underway and scheduled for adoption in 2013.[142] |

“Everything

Hurts:” Other Health Consequences of Child Labor in

Artisanal Gold Mining

Respiratory Diseases

Children in mining areas suffer from respiratory diseases, ranging from bronchitis to pneumonia and tuberculosis (TB).[143] In the mining areas, respiratory diseases are partly caused by the dust emanating from artisanal mines during the work process, and can affect child laborers as well as other children living in the vicinity. Mory C., an 11-year-old boy from Baroya, complained:

In the mine, I transport the ore from the shaft to the panning [place].... Most often, I have pain in the joints and in the chest.[144]

Respiratory diseases are common among miners around the globe, and one disease, silicosis, has been specifically associated with mining.[145] Doctors in Mali do not have the equipment and capacity to diagnose silicosis, so there are no data on the prevalence of silicosis for the country.[146]

Musculoskeletal Problems

Of 33 child laborers interviewed, 21 said that they suffered from back pain, neck pain, headaches, or pains in their arms, hands, or joints. Digging, pulling, lifting, and carrying heavy ore caused such pain. For example, Oumar K. complained about the health consequences of digging shafts, working underground, and pulling up heavy buckets:

When you leave the mine and you arrive home, everything hurts, particularly your chest and back. I’ve also had some problems with breathing, I would sometimes cough.[147]

Such hard labor can affect children’s long-term growth, leading to skeletal deformation of the back and neck, and accelerating joint deterioration.[148]

Extended periods of bending over to dig or pan, and repetitive movements, such as crushing rock with manual tools, can result in similar pain and in long-term physical consequences.[149]

Injuries from Accidents

Children in mining areas risk injury from sharp tools, flying and falling rock, and frequently collapsing shafts. For example, in February 2011, a 15-year-old boy in Tabakoto cut himself with a hoe in the tibia (shinbone).[150] Children crushing stone may be cut by flying rock shards or cut themselves with tools.[151]

The transport of ore can also lead to accidents, as is illustrated by the experience of Mamadou S., who was about six years old:

Once I had an accident. I injured my finger. I wanted to carry a rock and it fell on my foot. I was taken to the health center. This happened about two months ago.[152]

The father of Mamadou S. insisted that work in the mine was good for the education and training of his son, and claimed that Mamadou was four years old.[153]

Child laborers sometimes fall down shafts when they work underground, or fall while climbing down or up, as do adults.[154] A nurse in Tabakoto treated an 11-year-old boy who fell into a shaft and fractured his hand.[155]

As described above by Oumar K., a child laborer, shafts do collapse.[156] These frequently result in fractures, open wounds, back injuries, and other injuries, and can even lead to death.[157] A doctor in Kolondiéba circle noted that there are shaft collapses in Mpékadiassa and Worognan mines every month, although Human Rights Watch has not been able to verify this.[158]

Several cases of mine collapses illustrate the potential danger for child laborers, even though no children were affected in these incidents. In April 2010, an adult died at a Kéniéba mine when his head was smashed during a shaft collapse, and two others died from other shaft collapses in the area during the same year.[159] At least three workers were killed in a shaft collapse in Worognan mine in late 2010 or early 2011, spreading fear among many workers. While the mayor put the number of victims at three and tried to downplay the incident, other workers at the mine said that the number of victims could have been higher.[160] A Ministry of Labor official also witnessed a shaft collapse during a visit to a mine in Kéniéba region.[161]

Even children who do not participate in the gold mining visit the mines and are exposed to risks. This includes children who are taken by their parents to the mine due to lack of childcare. Older siblings faced the difficult task of protecting younger siblings from falling into shafts and other accidents.[162] A doctor in Kéniéba treated two children who fell into a shaft in a mine near Kéniéba. The children were around five and six years old.[163] In Baroya, a boy of about three years fell into a shaft and injured his arm.[164]

Working Hours and Pay: Between Family Support and Exploitation

Working Hours

The children we interviewed said work days often lasted for as long as 11 hours, from 7 or 8 a.m. to about 6 p.m.[165] An ILO study on child labor in artisanal mining in Mali found that children averaged nine hours of work a day.[166] The work day is nearly continuous. For example, Haroun C., 12, who has never attended school, told Human Rights Watch that he works at the mine from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., and that his joints hurt him at night.[167] Some children said they took lunch breaks or rested for a moment when they felt exhausted or in pain.[168]

Artisanal mines usually have one day of rest per week for everyone, including children. This is thought of as a day for the spirits of mining.[169]

Some child laborers attend school, but work full days in gold mining during holidays and weekends. They sometimes also work at the mines after school or skip lessons to go the mines.[170] Of 33 child miners interviewed, 16 went to school. Most of these children were younger and attended primary school. One child laborer who attends school was 12-year-old Issa S., who complained the impact of long work hours on his health:

I work here with my father. I pull up the buckets with ore. It is ore mixed with water. During school holidays, I am here every day from 7am to 6.30pm, except Monday [rest day]…. I started working here when I was 10. My job has always been to pull the buckets up…. I have backaches from the heavy loads, on the lower back. It is really heavy. I would really like to stop. I don’t have a break apart from lunch break.[171]

Pay

Children who work in artisanal mines are often not paid. If they do get paid, they give most of the money to their parents or guardians; adolescents who are by themselves often send money to their parents. When children work for people other than their parents, they face an additional risk of abuse and exploitation.

Children’s Economic Contribution towards Their Own Family

Many children contribute to the production process but do not obtain the gold at the end of it. Their work is considered part of a group work product.[172]

Some child laborers get paid. Pay is irregular, varies greatly, and is based on the amount of gold mined.[173] Most commonly, child laborers give the money to their parents or guardians, to add to the family income. Of 17 children who told us that they were earning money, 13 had to give it to their parents or guardians.[174]

When parents are not present, children sometimes earn money to send it to them. One such child was Nanfadima A., 11, who said:

I live in Tabakoto with my uncle, the younger brother of my father. My parents are at another gold mine, further away.… I take the gold and bring it to the trader in Tabakoto. I give the money to my father. I get 2,000 or 3,000 CFA francs (about US$4.36 to US$6.54) for one piece of gold, say, two times per week.[175]

A 15-year-old boy, Abdoulaye M., also sent money home:

I have come to earn money in Baroya. My parents are in Manantali, they told me to come here and look for money. So my older brother brought me here and he comes [regularly] to pick up the money that I have earned.[176]

Another boy, Tiémoko K., 15, also earned money for his parents who lived far away. He was subjected to the same exploitative rules as adult artisanal miners, having to give two-thirds of his ore to another gold miner who is considered the owner of the shaft:

My parents are in Kita, I have come here to Baroya with the help of a friend of my father. I am here to earn money for my parents. I have been here about 12 months. I earn between 3,000 and 4,000 CFA francs (about $6.54 to $8.73) a day. … I work for the owners of shafts. For every three bags we pull out, I get one.[177]

Children Earning Their Own Money

Some adolescents earn money for themselves, particularly when they have migrated and live alone. Still, this was not always enough to survive. Ibrahim K., 15, said:

The problem is having enough food. If we don't have enough gold, we don't have enough money for food. Our team sells the gold to a dealer and we share the money.[178]

Adolescents have occasionally earned a significant amount of money, and kept some of it for themselves. The prospect of earning money encouraged them to work in artisanal mining, while they were largely unaware of the risks. One boy, Julani M., told us that he once earned 30,000 CFA francs (about $65) in two days, and that he bought clothes with the money.[179] Several adolescent girls told us proudly that they earned money. One of them, Fatimata N. from Burkina Faso, said that she had once earned 80,000 CFA francs (about $174), and kept a portion to buy herself clothes. She concluded: “The work is good for me.”[180] Aïssatou S., 17, earned her own money and used it for her trousseau (clothes and other items for a wedding). She said:

I have got a little bit of money from the gold. Since the start here, I have earned about 40,000 CFA francs (about $87). I have bought clothes and cups for my trousseau from it.[181]

Some parents also occasionally rewarded their children with small amounts of money or a decigram of gold. For example, Moussa S., who is six years old, sometimes gets 100 CFA francs (about $0.21) as a gift from his father.[182]

Children’s Exploitation by Guardians

According to the ILO, about 20 percent of children in artisanal mining work for adults who are not their parents, such as an employer or a relative. This frequently results in economic exploitation.[183]

One such case was Boubacar S., who lived with guardians. His biological parents were working somewhere else, and placed him with a family with whom they were acquainted. Boubacar said he earns about 1,000 CFA francs (about US$2.18) per day and has to hand over his earnings to his guardian immediately. He told us in tears:

I was at school but my stepfather took me out. I left school about six months ago, at the beginning of the school year. On Mondays my stepfather requires me to make bricks. On other days, I work in the mine and give all the earnings to my stepfather. I get about 1,000 CFA francs per day. I give it all immediately to my stepfather…. I transport the ore from the shaft to the place where they put it into sacks. I use the cart with the donkey for this.… I was first or second in class together with another girl. I liked school…. There was also a problem that my step-parents had not paid the school fees. So I had to repeat second grade because of that, not because I was doing badly in school… The work is hard. I often have belly aches and headaches. I feel that the work is too much for me ... because of the weight. I am often bent over.… My parents are [gold miners] in another village…. My stepfather treats me as if I am not a human being.[184]

Boubacar’s teacher confirmed that the boy was treated badly by his stepfather. The stepfather had told him that he would not pay the school fees if the child refused to do the work he asked him to do.[185]

Mariam D., the girl in Worognan who was very upset that her stepmother was taking the money she earned told Human Rights Watch:

My stepmother takes all the money they pay for me.… I don’t get any money from the work, my stepmother gets it. She doesn’t give me anything.[186]

Trafficking

Conditions for child trafficking are ripe in Mali’s artisanal mines because of exploitative labor conditions, as described above. Children who migrate without parents and work for other adults are particularly vulnerable to trafficking. According to the ILO, about two-thirds of child laborers surveyed in Malian artisanal mines are migrants.[187]A regional survey about artisanal mining found that 10 percent of child laborers in artisanal mines in Guinea, Mali, and Burkina Faso were foreigners from other West African countries who lived in the mines without their parents.[188]

During our research, we met several children who were victims of exploitation and whose situations might have amounted to trafficking. One was Boubacar S., 14, from Sensoko, in the Kéniéba area, whose situation is described above.[189] He was living with guardians who treated him “as if I am not a human being.” They forced him to work in artisanal mining and brick making. His parents were gold miners who moved to another gold mine in Mali; they were not in contact with him.[190]

Human Rights Watch also interviewed children from Burkina Faso and Guinea who might have been victims of trafficking. Salif E., 15, was sent from Burkina Faso to Mali by his parents, and travelled to Worognan mine with two other boys who were relatives. They were accompanied by the head of the Burkinabe community, who was Salif’s uncle, and they also worked for him.[191] When we interviewed Salif, he had been in the mine for about three weeks and had not yet been paid.

Leaders of migrant communities play a key role in organizing life of the foreign mining workers.[192] The head of the Burkinabe community in Worognan, Salif E.’s uncle, explained that around 60 persons were working for him. A local gold trader confirmed that he employed several children.[193]

Coercion

The majority of children in child labor dislike the work they do, but do it to help their parents, according to a recent survey.[194] Even when children are not victims of trafficking, they often experience a degree of coercion when working in artisanal mining. The decision to send children to work in the mines—whether by themselves, with the family, or other guardians—is almost always made by parents, and children have little say in the matter. This situation of coercion gets worse when parents or guardians exert psychological pressure or threaten physical abuse.

Several children told us that they would like to leave gold mining work, if they could.[195] This was the case of Mariam D., whose stepmother made her work in the mine whenever there was no school and obliged her to hand over all the earnings. The girl was upset about this, but did not know how to get out of this situation. She told Human Rights Watch: “I don't want to work in the mines. I want to stay in school.”[196]

Aminata C., who is 13 years old, said she panned for gold and amalgamated gold with mercury. Although her father gave her pain medicine when she suffered from the effects of the hard work, she said her father insisted that she continue working:

I want to get out of this work, but if I refuse to go to the mine, my parents beat me.[197]

Hamidou S., who was about eight years old and in third grade, said:

I work on the mine during the holidays, usually every day from morning to evening. I dig shafts with a pickaxe.I also do childcare…. Sometimes my neck and back hurt because of the digging work.… My parents tell me to work at the mine.[198]

In some cases, children feel they would like to leave the work, but cannot. In the above-mentioned ILO study, 39 percent of children interviewed stated that they could not stop and leave the gold mining work as they wish.[199]

Other Child Labor in Mining Communities

The existence of artisanal gold mines often leads to the creation of small commercial centers. Children perform many other forms of child labor in these communities. Some work in artisanal gold mining and do other work at the same time.

Agriculture and domestic labor are the most common forms of child labor in Mali.[200] Boys frequently work in agriculture, sometimes leaving the mines during the harvest. Others work entirely in agriculture.[201]

Many girls in mining communities do domestic labor, in their own families or the host families they live with.[202] While most of the domestic work is done in the home, some takes place at the mine. Women often take smaller children with them to the mine because they lack childcare, and use their older children to look after the small siblings.[203] Children frequently have to carry younger siblings on their back, feed them, and protect them from injury. In one case, a mother told us that her four-year-old daughter was looking after her little sister in the mine.[204]

Children also work in other businesses. For example, they sell water or food, or make bricks or clothing.[205] In addition, children are involved in sex work, one of the worst forms of child labor.[206]

Attitudes to Child Labor

Child labor is common and is widely accepted in Mali. A recent survey on attitudes towards child labor confirms that parents commonly view child labor as acceptable.[207] Teaching a child how to mine gold is considered part of socialization.[208] Government officials also told Human Rights Watch that child labor was part of Malian culture. A ministry official described child labor as “educative” (socialisant), as it teaches children the value of work.[209]

We interviewed a miner who claimed to own gold worth well over US$10,000. He sent his son Mamadou S. to the mine although he did not need the income. He said:

I let my son do this for education. [Mamadou] collects the stones and carries them.[210]

Community leaders in Worognan emphasized what they saw as positive effect of children working in gold mining, namely that the community now had the means to buy larger items such as new roofs, bicycles, or machines for agriculture.[211]

IV. Sexual Exploitation and Violence

Sexual Exploitation

Sexual exploitation is common in mining areas, particularly in large mines that bring together many different populations from within and outside Mali.[212] Child prostitution is inherently harmful and a worst form of child labor under international law. International law also prohibits sexual exploitation.

Some girls self-identify as sex workers. NGOs working on HIV prevention and treatment in mining areas have reached out to adult and child sex workers in artisanal mines in the Sikasso and the Kayes region, including in large sites such as Alhamdoulaye and Massiogo in Kadiolo circle, M’Pékadiassa in Kolondiéba circle, and Hamdallaye in Kéniéba circle.[213]

One NGO found that over 12 percent of the sex workers they worked with were between the ages of 15 and 19. It also found that the large majority of sex workers were foreigners, mostly from Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire.[214]

In Worognan mine, in the Sikasso region, women and girls, mostly Nigerians, worked as sex workers. Stella A., an 18-year-old sex worker, told us about the climate of violence in which she works:

I am from northern Nigeria. When I was 17, a woman brought me from Nigeria to Bamako and left me there. My sisters [Nigerian women] brought me here a month ago…. Some bars do have young girls, 12 years old…. We have to avoid the fights. Some men come and are bad to us. Some make us scared. They become aggressive when they're drunk…. There was no money in Bamako, but it was safer. Here it's more dangerous and not much money [either]. I haven't been hurt but I'm scared. I would like there to be more police.[215]

Mariam D., about 11 years old, worked in Worognan mine and described her surroundings:

There are prostitutes there, girls older than me. They go with the boys. I know some of the boys had hit the girls [sex workers] or hurt them.… I have seen fights at the mine, between men. The gendarmes have come, I saw them take a boy away in handcuffs, for hurting a girl.[216]