(Beirut) – Lebanese Internal Security Forces threaten, ill-treat, and torture drug users, sex workers, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in their custody, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The report was released on the United Nations International Day in Support of Victims of Torture.

The 66-page report, “It’s Part of the Job: Ill-treatment and Torture of Vulnerable Groups in Lebanese Police Stations,” is based on over 50 interviews with people arrested for suspected drug use, sex work, or homosexuality over the past five years who reported that members of the Internal Security Forces subjected them to abuse, torture, and ill-treatment. All of the members of these marginalized social groups interviewed by Human Rights Watch faced obstacles to reporting abuse and obtaining redress, leaving the abusers unaccountable for their actions.

“Abuse is common in Lebanon’s police stations, but it is even worse for people like drug users or sex workers,” said Nadim Houry, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “The abuse of prisoners, especially the most vulnerable people in society, isn’t going to stop until Lebanon ends the culture of impunity in its police force.”

Lebanon, with substantial assistance from donor countries, has taken a number of steps to expand and reform the Internal Security Forces in the last five years. The reforms include a new Code of Conduct setting out standards of behavior and obligations rooted in Lebanese law and international human rights principles. But these efforts remain inadequate and have failed to address ongoing abuses by personnel, Human Rights Watch said.

Lebanese authorities should establish an independent complaints mechanism to investigate torture allegations, and donor countries should ensure that aid to the Internal Security Forces supports the establishment of real accountability mechanisms.

Former detainees reported torture and mistreatment in all of the facilities that Human Rights Watch investigated including in Beirut’s Hobeish police station, Gemmayze police station, Baabda police station, Msaitbeh police station, Zahleh police station, Ouzai police station, Saida police station, police intelligence in Jdeideh, and in pre-trial detention in Baabda women’s prison.

“They took me to interrogation naked, poured cold water on me, tied me to a desk with a chain, and hung me in the farrouj position,” said “Mohammad,” who was arrested for drug possession, describing being suspended by the feet with hands tied to an iron bar passed under the knees. “They broke all my teeth and nose, and hit me with a gun until my shoulder was dislocated.”

The most common forms of torture reported were beatings with fists, boots, or implements such as sticks, canes, and rulers. Seventeen former detainees said they were denied food, water, or medication when they needed it, or that their medication was confiscated. Nine reported being handcuffed in bathrooms or kept in extremely uncomfortable positions for hours at a time. Eleven said they were forced to listen to the screams of other detainees to scare them into cooperating or confessing.

Twenty-one of the 25 women interviewed who had been arrested for suspected drug use or sex work told Human Rights Watch that police had subjected them to sexual violence or coercion, ranging from rape to offering them “favors” – cigarettes, food, more comfortable conditions in their cells, or even a more lenient police report – in exchange for sex.

Physical violence was used both to extract confessions and as punishment or to correct the detainee’s behavior. Nine people arrested for drug use or homosexuality said their socio-economic status seemed to play a large part in determining how police treated them.

The ill-treatment and torture were accompanied by other key violations. Interviewees said they were denied phone calls to family members, access to lawyers, and needed medical care. While article 47 of Lebanon’s Code of Criminal Procedure limits detention without charge to 48 hours, renewable once with permission from the public prosecutor, this limit is often violated.

The police torture and ill-treatment are grounded in inadequate or badly implemented legal protection, a judicial emphasis on confessions over other types of evidence, a culture of impunity, and lack of proper oversight mechanisms, Human Rights Watch found.

The mechanisms that do exist, such as the Internal Security Forces human rights committee, are understaffed and exercise no real power. The Interior Ministry has a separate complaints mechanism, but it is flawed and difficult to navigate and follow up. A code of conduct issued by the Internal Security Forces in January 2011 sets out standards of behavior and obligations rooted in Lebanese law and international human rights principles, but it has not been fully implemented.

The judiciary regularly ignores complaints against abusive policemen, Human Rights Watch found. In only three cases did the investigative judge order an investigation into allegations that confessions were made under duress. Five former detainees told Human Rights Watch that investigative judges dismissed outright their allegations of mistreatment, intimidation, and abuse, while 12 said that investigative judges did not take allegations of torture and forced confessions into consideration.

“Lebanon’s ongoing political paralysis should be no excuse to avoid essential police reforms,” Houry said. “If anything, the current political and security crisis highlight the need for accountable and rights-respecting security forces.”

While access to redress for police abuse is generally difficult, the report found that it is particularly challenging for sex workers, drug users, and LGBT people. Of the 52 people interviewed who alleged ill-treatment, only six filed complaints, and judges ordered inquiries in only two of these cases.

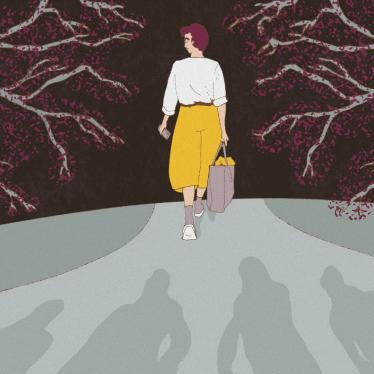

The threat of exposure of their conduct or sexual orientation, which can lead to negative social consequences in Lebanon, is a barrier to reporting for members of these groups. The ways laws that criminalize sex work, homosexuality, and personal drug use are enforced exacerbate the problem and present a major obstacle to reporting police abuse.

Lebanon should uphold its international commitments by amending its definition of torture and putting into effect the provisions it made a commitment to uphold when it signed the Convention against Torture and the convention’s Optional Protocol. In particular, it should create a “national preventive mechanism,” an independent body tasked with monitoring detention centers.

Lebanon should also ensure accountability for Internal Security Force abuses with an effective and accessible complaints mechanism and transparent procedures, Human Rights Watch said. It should revise its Code of Criminal Procedure to better safeguard the rights of detainees and repeal laws criminalizing homosexuality, drug use, and sex work.

Donor countries such as the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and France have invested significant amounts of aid in equipping, training, and improving the Internal Security Forces. These countries should ensure that their aid supports the development of internal oversight and accountability mechanisms, including an independent body to investigate allegations of torture and ill-treatment. They should not fund units credibly found to abuse human rights and make resumption of funding to such units subject to enactment of reforms that guarantee an end to abuses and accountability for past violations.

“Donors need to put more emphasis on developing oversight and accountability mechanisms for torture and abuse by security forces,” Houry said. “Ultimately, the Lebanese security forces will be judged not by the quality of its equipment, but by the behavior of its members.”

Selected Statements from “It’s Part of the Job”

“Mohammad,” 30, told Human Rights Watch that he spent 11 days in detention in the Zahleh police station in 2007 after police arrested him for drug possession. He said that the police beat him severely until he confessed to using drugs:

They took me to interrogation naked, poured cold water on me, tied me to a desk with a chain, and hung me in the farrouj position [A torture technique in which the victim is suspended by the feet with hands tied together to an iron bar passed under the knees]. They broke all my teeth and nose, and hit me with a gun until my shoulder was dislocated.

“Nadim” told Human Rights Watch that he spent two days in Hobeish police station in October 2010 after police arrested him when they could not find his brother, whom they suspected of drug dealing. When they found no evidence that Nadim had engaged in drug dealing himself, he says, they changed the charge to homosexuality. Nadim was repeatedly beaten, threatened, and subjected to an anal examination:

The intimidation and the beatings never stopped [in Hobeish]…. [An officer] asked me why I had messages and names of gay men on my phone, I asked him whether it was illegal to speak to gay men. He hit me again so hard my eye split and I began bleeding. I begged him to stop hitting my face but this egged him on further and he hit me even harder. He forced me to sign a confession that I have sex with men, all the while hurling punches and abuse at me. He then made me take off all my clothes and looked at me, told me I’m a faggot, insulted me, threatened me.

The next day, two more men came in and interrogated me again. By this time the drug issue was dropped, the case was now about homosexuality…When I told the interrogating officer that I was forced to confess to having sex under duress, he got a thick electricity cable and whipped my palms. He then said that he would get a forensic doctor to check me …He kept intimidating me, trying to get me to confess again…The exam turned out negative, and so they had no choice but to release me without charge.

“Soumaya,” a sex worker who had been in pretrial detention in Baabda prison for nine months when she spoke to Human Rights Watch, said that it was expected that police officers would try to have sex with women arrested for prostitution:

It’s normal. They don’t see us as human beings. They know that we are poor, that we probably don’t have families, and that no one asks about us. We’re easy to take advantage of. I was arrested three times in the past five years. Every time a police officer would come to the cell and try something with me. At first I protested, I fought back, but then I understood that it’s useless. If you want to be treated well, you have to have sex with them. If you do that, they will take care of you. Otherwise you could get beaten, insulted, even raped. If you let them sleep with you, they might even help you get out without charges.

“Gharam” told Human Rights Watch that she was raped by a police officer in the Gemmayze police station in February 2012. She was arrested after police detained her daughter for sex work and charged her with facilitating her daughter’s prostitution activities:

I stayed in Gemmayze station for three days and they treated me and my daughter very badly…. During my time there one of the officers came to me at night and told me that if I didn’t let him sleep with me, I’d go to jail for 10 years and my daughter for even longer. I was so scared that I let him. The next day I was transferred to the Baabda station where I spent another three days before going to Baabda prison. I didn’t tell anyone what happened. I was too scared. He had threatened me to stay quiet.