Switzerland is a country of paradoxes. Rich with humanitarian traditions, home of international human rights bodies and organizations, and numerous global companies, it is also a place where the debate around migration has grown increasingly hard-line. The results of that shift were manifested in the recent constitutional referendum for automatic deportation of foreigners convicted of crimes. The vote has drawn concerns from multiple quarters, including the UN's human rights and refugee agencies, both headquartered in Geneva.

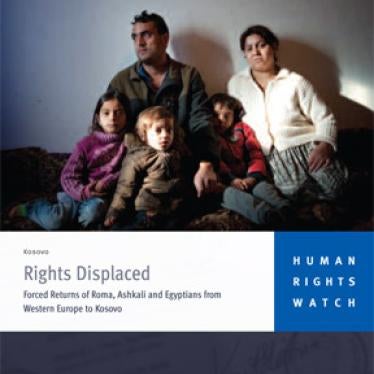

Faced with a progressive hardening of attitudes toward foreigners and migrants, many people who live in Switzerland and who have a continuing need for protection are vulnerable to deportation. They include members of Kosovo's minority groups - the Roma, and the Albanian-speaking Ashkali and Egyptians.

During the Kosovo war of 1999, Switzerland gave shelter to Kosovo Albanians, the majority ethnicity who had been discriminated against and persecuted during the dark years of the Milosevic area. After the war ended, Switzerland also welcomed Kosovo's minorities, who fled after the conflict ended, fearing retaliatory attacks.

Today, the Kosovo diaspora in Switzerland includes 164,000 people. About 40,000 among them are Swiss citizens, 120,000 have work permits, 3,000 remain on the basis of temporary protection mechanisms, and 1,000 have pending asylum claims. The last two groups are vulnerable to deportation, if their asylum application is not successful or their temporary protection status is revoked.

Even though its declaration of independence in February 2008 was expected to bring more peace and prosperity to Kosovo, life has not improved for many living there. Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians face levels of poverty, discrimination, marginalization, deprivation and misery amounting to grave human rights abuse.

The UN refugee agency's guidelines call on countries not to deport Roma to Kosovo and advise that Ashkali and Egyptians should be returned only after a careful individual risk assessment and in a phased, responsible manner. Nevertheless, various European countries, including Switzerland, have over the years sent Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians back to Kosovo, contending that the situation has "normalized" and that members of these groups no longer need special protection. In February, Switzerland and Kosovo signed a bilateral readmission agreement, opening the door to deporting more Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians.

Those forced back to Kosovo receive little or no assistance from international or local agencies. They have problems finding housing, health care, employment and social welfare services. They frequently face obstacles getting identity documents and repossessing property. Some end up de facto stateless. Their children stay out of school for lack of help in mastering language skills and curriculum differences.

The burden of helping the forced returnees falls on the already existing Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities, pushing them into even more acute poverty. That in turn risks destabilizing the fragile security situation in Kosovo - a concern that has been flagged by, among others, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and a range of Council of Europe bodies.

It is appalling how the current mood, epitomized by the dissemination of "Ivan the rapist" posters, depicts a specific group of people - persons from the Balkans, many of whom have lived in Switzerland for decades - as criminals. It also distorts the reality, which is that, despite the anti-migration and racist rhetoric, the Balkan minorities continue to require protection and are more vulnerable than ever. It is important for Switzerland to recognize this, adhere to international human rights law and live up to its humanitarian tradition.

Sandra Wolf is a member of Human Rights Watch's Geneva Committee. Wanda Troszczynska - van Genderen is the Western Balkans researcher at Human Rights Watch