- This submission concerns the privacy rights of children and issues relating to their independence and autonomy. It focuses on the importance of privacy for children with respect to their sexual and reproductive health and rights, physical and emotional well-being in school, safety in the online space, and the protection of their information online.

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

- States’ obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights include areas of sexual and reproductive health and autonomy. Where access to safe and legal abortion services are unreasonably restricted, a number of human rights may be at risk, including the right to privacy.

- The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) has emphasized, “All adolescents must have access to confidential adolescent-responsive and non-discriminatory reproductive and sexual health information and services, available both on and off-line, including … safe abortion services.”[1] It has recommended that governments ensure that children have access to confidential medical counsel and assistance without parental consent, including for reproductive health services.[2] It has specifically called for confidential access for adolescent girls to legal abortions.[3] The Special Rapporteur on the right to health has also strongly affirmed the importance of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive rights, urging states to strengthen laws, policies and practices to respect, protect, and fulfill those rights.[4]

- Children have a right to freely express their views in all matters affecting them and, in accordance with children’s age and maturity, their views should be given due weight.[5] Therefore, it is crucial to take into account the right to be heard when interpreting and implementing all other rights.[6] In the context of decisions about abortion, the CRC has affirmed that pregnant adolescents’ views should always be respected.[7]

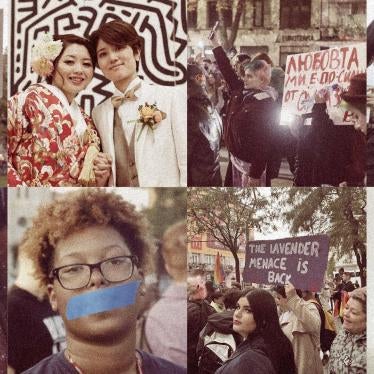

- Guaranteeing all adolescents, defined by the UN as persons between the ages of 10 and 19,[8] the right to make autonomous decisions about their sexual and reproductive health and rights is a critical component of the right to equality and nondiscrimination. Denial of this right has a disproportionate impact on girls and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. Treaty bodies recognize that overly restrictive laws on sexual and reproductive health services–such as laws restricting the legality of specific services and requiring third-party authorization–can violate the right to nondiscrimination.[9]

Criminalization of Abortion

- Human Rights Watch research has shown that criminal penalties for abortion drive some pregnant children and adolescents to have illegal and unsafe abortions. A 2018 global report on abortion found that 25 million unsafe abortions are performed every year, “virtually all (97 percent) of which are in the developing world.”[10] The report found that 8 to 11 percent of all maternal deaths globally are related to abortion, leading to an estimated 22,800-31,000 preventable deaths each year.[11]

- The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) has recommended that states ensure that the personal data of patients undergoing abortion remain confidential.[12] CESCR and the CRC have commented on the problem of women and girls seeking health care for complications from unsafe abortions being reported to authorities.[13] Likewise, the Human Rights Committee and the Committee against Torture have called for protection of privacy and confidentiality for women and girls seeking medical care for complications related to abortion.[14]

- International human rights bodies have upheld that forcing a woman or girl to carry to term a pregnancy resulting from rape has severe mental health consequences and constitutes a violation of her rights, including to privacy and bodily integrity.[15] Due to either total criminalization or the presence of unlawful barriers, many girls are denied an abortion following sexual violence.[16] Approximately 15 million girls and young women (aged 15 to 19) worldwide have experienced forced sex at some point in their life. In most countries, girls are most at risk of forced sex by a member close to the family or social group.[17]

- More than 1.1 million girls have suffered sexual violence in Latin America and the Caribbean.[18] It is the only region of the world where the rate of pregnancy for girls under age 15 is rising; most of these pregnancies result from rape, often by men who are relatives or otherwise known to the victim.[19] Sexual violence itself has devastating consequences on the lives of girls. When that sexual violence leads to pregnancy the effects cascade, compounding the trauma girls already face.[20]

- Human Rights Watch has documented the devastating consequences, including for pregnant children, in countries where abortion is heavily restricted or completely banned, including in the Dominican Republic,[21] El Salvador,[22] Brazil,[23] Honduras,[24] and Ecuador.[25]

Forced Parental Involvement in Abortion Decisions

- Thirty-seven US states have laws requiring people under age 18 to involve a parent in their abortion decisions, either by requiring parental notification, parental consent, or both. In most states, young people may seek permission from a judge to obtain an abortion without parental involvement through a judicial bypass process and demonstrate that they are 1) sufficiently mature to make an abortion decision without parental involvement, or that 2) parental involvement is not in their best interest. Human Rights Watch has done preliminary research in three states that mandate parental involvement in young people’s abortion decisions: Florida, Illinois, and Massachusetts. Our findings indicate that such laws pose a significant barrier to abortion access for young people and threaten or undermine several rights protected under international human rights law, including the right to privacy.

- Studies show that the majority of young people voluntarily involve a parent or another trusted adult in their abortion decision, whether or not the law requires it, particularly when there is a close supportive relationship with a parent.[26] But for the minority of young people who do not involve a parent–often because they fear abuse, deterioration of family relationships, being kicked out of the home or forced to continue a pregnancy against their wishes, or because their parents are not part of their lives–mandated parental involvement is deeply harmful and delays or prevents access to abortion care.[27]

- To obtain a judicial bypass, young people typically have to demonstrate to a judge that they are sufficiently mature to make the decision to terminate an unwanted pregnancy without involving their parents, or that involving their parents is not in their best interest. When young people fear that parental involvement could trigger violence or alienation from their families, they have to find ways to initiate the process without their parents finding out, including securing transportation and arranging time away from school. The process is challenging and intimidating, and young people may be unable to navigate it.

- Mandated parental involvement in an abortion decision can be particularly difficult for young people who have experienced violence in the home or have become pregnant from sexual violence. Two attorneys in Florida told Human Rights Watch they had represented clients who were pregnant from rape or incest and sought judicial waivers because they had been removed from their parents’ care and were under the care of the Florida Department of Children and Families. Even in these circumstances, the state was unable to act as a parent or legal guardian to satisfy the state’s parental notification for abortion requirement, so the clients were forced to appear in court to explain why they could not involve their parents. “For anyone who is a victim of assault, one of the most difficult things is to relive those moments [of violence],” one attorney said. “We’re continually asking [them] to relive the trauma.”[28]

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Affirm that promoting and protecting children’s right to privacy requires ensuring abortion is safe, legal, and accessible and with the greatest possible respect for children’s autonomy in abortion-related decisions.

Urge states to take urgent action to decriminalize abortion and lift harmful restrictions on abortion access, including by repealing requirements mandating parental involvement in children’s and adolescents’ abortion decisions.

Comprehensive Sexuality Education and Confidential, Adolescent-Responsive Health Services

- All children and adolescents have a right to information about sexual and reproductive health, as guaranteed under international law. The right to information is set forth in numerous human rights treaties,[29] and includes both a negative obligation for states to refrain from interference with the provision of information by private parties and a positive responsibility to provide complete and accurate information necessary for the protection and promotion of rights, including the right to health.[30] The Committee on the Rights of the Child and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights have clarified that the right to education includes the right to comprehensive sexuality education.[31] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has also affirmed that information and services related to sexual health should be confidential: “All adolescents should have access to free, confidential, adolescent-responsive and nondiscriminatory sexual and reproductive health services, information and education.”[32]

- Comprehensive sexuality education provides adolescents with medically accurate, developmentally appropriate, rights-based, and inclusive information to make informed and safer decisions about their health. Through comprehensive sexuality education, adolescents can better understand their bodies, take steps to prevent and treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs), understand where to go for free or low-cost reproductive health services, including contraception and safe abortion services, explore their sexual orientation and gender identity, build healthy relationships, and navigate consent. Access to comprehensive information on sexual and reproductive health can save lives and reduce preventable deaths, including deaths from cancers associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV). Yet schools around the world are failing to provide this critical information to young people.

- Human Rights Watch has observed a troubling backlash against efforts to provide children and young adults with adequate information and comprehensive sexuality education in many parts of the world, including in Brazil,[33] the Dominican Republic,[34] Ghana,[35] Kenya,[36] and Poland.[37] Opposition to sexuality education is often rooted in harmful, stigmatizing, patriarchal, or homophobic and anti-LGBT beliefs—sometimes presented as national traditions or cultural values. These include the propositions that young people will grow out of or cannot yet understand their sexual orientation or gender identity, that people who engage in sex outside marriage should be stigmatized or punished, and that suppressing access to information about sexuality will somehow delay young people’s sexual initiation.

- Human Rights Watch research in 2019 in Alabama, a state with high rates of STIs and cancers related to HPV, including cervical cancer, shows how lack of access to information on sexual health leaves adolescents and young people without the information they need to take steps to stay healthy.[38] Alabama does not mandate comprehensive sexuality education and if schools do decide to teach it, the State Code requires a focus on abstinence. Most young people Human Rights Watch spoke with received abstinence-only education in school that withheld accurate information on sexual health, stigmatized adolescent sexuality, reinforced heteronormativity, and left many of them feeling ashamed of their bodies and behaviors. Many young people reported lacking access to accurate information on their sexual health and not knowing where to go or who they could talk to in confidence about their private health concerns and questions. As a result, many young people in Alabama turn to their friends and to the internet for information on their sexual health, practices which can perpetuate dangerous misconceptions and inaccuracies, leave young people with major gaps in information, and hinder their ability to make informed decisions around their health.

- Without assurances that their confidentiality would be protected and fearing that health workers might divulge private information to community members, especially in small communities, some young people chose not to seek out necessary health services.

- Young people also reported lacking privacy to openly discuss their health concerns with medical providers. In addition, several young people reported that their parent was the sole decision-maker in whether or not they received the HPV vaccine, an effective cancer prevention tool that protects against most strains of HPV that can lead to cancer. Due to its association with an STI, many parents did not see the need to vaccinate their child against HPV or believe it was necessary. Without the ability to speak privately with a medical provider about their sexual behaviors—often due to shame and stigma around adolescent sexuality—or to meaningfully contribute to a decision to receive the HPV vaccine, which could protect them against a common STI and several forms of cancer, many young people who spoke to Human Rights Watch were left at a greater risk of negative health outcomes.[39]

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Urge all states to take measures to combat the stigma around adolescent sexuality and promote healthy adolescent sexual practices, including through national and local campaigns involving and designed by young people.

Urge all states to implement mandatory comprehensive sexuality education that complies with international standards and is scientifically accurate, rights-based, and age-appropriate. Ensure that the curriculum reaches students from an early age and builds incrementally to equip them with developmentally relevant information about their health and wellbeing. Ensure that teachers are adequately trained to teach this curriculum, and schools provide safe spaces for children and adolescents to discuss issues in a confidential, non-stigmatizing manner.

Urge all states to expand access to appropriate, adolescent-friendly, confidential, non-stigmatizing health services for a full range of sexual and reproductive health needs, without requiring parental notification or consent. Ensure that staff are trained to manage individual cases without stigmatizing young people, particularly children who are already sexually active.

Ask that all states ensure that health centers do not stigmatize adolescents who are sexually active, and that they are staffed with medical personnel qualified to provide confidential and comprehensive adolescent health services.

Bodily Autonomy

- In some countries, school officials use harmful means to identify pregnant girls in schools, and sometimes stigmatize and publicly shame them. Human Rights Watch has found that in some African countries, officials conduct mandatory pregnancy tests on girls, either as part of official government policy or individual school practice.[40] These tests are usually done without the consent of girls. Mandatory pregnancy testing itself is a serious infringement of girls’ rights to privacy, dignity, equality, and autonomy, and when applied in schools to expel girls, a breach of children’s right to education.

- In Tanzania, Human Rights Watch found that officials routinely subject girls to forced pregnancy testing as a disciplinary measure and permanently expel those who are pregnant. Many girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch were regularly subjected to urine pregnancy tests in schools or taken to nearby clinics to get checked by nurses or health practitioners. On occasion, some girls and school officials reported that school officials physically examined students themselves by touching their abdomens. [41]

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Urge all states to abandon practices that stigmatize or discriminate against pregnant students, and to immediately end pregnancy testing in schools, and remove school bans on pregnant girls and young mothers.

Lack of Privacy and Confidentiality for Young Survivors of Sexual Violence

- Human Rights Watch’s research on school-related sexual violence, including in Senegal, Tanzania, and Ecuador, shows that children often do not report abuses when they fear that they will be stigmatized or subjected to further abuse by other adults in a position of authority. In Senegal and Tanzania, Human Rights Watch found that schools generally lacked confidential reporting mechanisms, child protection focal points, or school counsellors to file complaints and report allegations to police or prosecutor’s offices. It is also important to respect children’s right to privacy and protection. These barriers lead to under-reporting of school-related sexual violence.

- Many girls told Human Rights Watch they did not report incidents of sexual violence, especially when the perpetrators were teachers.[42] In Senegal, for example, Human Rights Watch observed that since the late 2000’s, the local media has consistently reported on the trials of teachers charged with sexual assault and often revealed the identity of young survivors of rape, their location, and the details of the offense.[43] The failure to protect survivors’ privacy by concealing their identities, and their negative portrayal in the media, deter young survivors from coming forward to report sexual violence, contributing to a very low rate of rape prosecutions.[44]

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Call on all states to ensure that students can equally and anonymously report any form of abuse, violence, sexual violence, or intimidation by students and teachers, by ensuring schools have functioning confidential and independent reporting and support mechanisms appropriate to the local school context. These could involve a child-friendly and free telephone hotline system set up to refer complaints directly to a relevant agency, and, preferably, a trained counsellor or school staff appointed to provide support to children affected, design measures to protect children, and in cases of sexual violence, confidentially report abuses to relevant authorities, or, including a local child protection committee or focal point, the local prosecutor’s office or specialized police unit, where available.

Urge all states to legally require head teachers and school officials to report any cases of sexual violence to local mechanisms, including the prosecutor’s office and the police.

Outing

- LGBT students face privacy concerns in schools related to their sexual orientation or gender identity. In the United States and South Korea, Human Rights Watch has interviewed LGBT students who have expressed concern about being “outed” by teachers and counselors who discover that they are not cisgender and heterosexual.[45] Requiring transgender students to carry identification, wear uniforms, or access bathrooms and locker rooms according to their sex assigned at birth can also effectively out them to other individuals who may not be aware that they are transgender.[46] Outing seriously jeopardizes LGBT students’ privacy. It also puts LGBT students at risk of bullying, harassment, and isolation; exposes them to family rejection; and can exacerbate anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns. States should respect students’ sexual orientation or gender identity and ensure they are able to access confidential, affirming mental health supports without fear of exposure or retaliation.

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Encourage states to adopt school policies and procedures that respect students’ sexual orientations and gender identities.

Urge states to ensure that all children and young people have access to accessible, confidential counseling and other mental health supports.

Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence Against Women and Girls

- Interrelated with the right to live free from technology-facilitated gender-based violence is the right to privacy, including children’s right to privacy. International human rights law, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Convention on the Rights of the Child, describes the right to privacy as the right to live free from “arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home or correspondence”—including in the online space.[47] Both the UN General Assembly and Human Rights Council have recognized the particular impacts of violations of the right to privacy in the digital age for women and children, and have emphasized the need for states to further develop preventive measures and access to remedies for violations of the right to privacy.[48] The Human Rights Council also expressed deep concern that all forms of discrimination, intimidation, harassment and violence in digital contexts prevent women and girls from fully enjoying their human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to privacy.[49]

- Human Rights Watch has conducted research in South Korea on non-consensually captured or shared intimate images. This abuse is referred to in South Korea as “digital sex crimes”; there is an important ongoing discussion about the best name for this abuse. (“Online gender-based violence” and “image-based sexual abuse” are also useful terms.) For the purposes of this submission, we use the term “technology-facilitated gender-based violence (GBV).” This form of technology-facilitated abuse is having a growing impact on children; it primarily affects girls, but children of other genders are also affected, and LGBT children may be disproportionately affected.[50]

- Technology-facilitated GBV can include direct violations of the right to privacy. These crimes take a wide variety of forms including: “spycams” placed in public spaces such as toilets and changing rooms or private spaces that film people without their consent; “upskirting” and other non-consensual capture of images in public; current and former partners taking or sharing intimate images non-consensually; children targeted for grooming on anonymous chat apps[51]; use of faked images to humiliate and harm people; and cases like the Nth room, in which perpetrators in South Korea coerced and blackmailed at least 58 women and 16 girls into taking part in explicit and sometimes violent content.[52] Technology-facilitated GBV is an evolving trend that urgently demands a comprehensive response by governments and private companies.

- The impact of these crimes is often underestimated by governments, companies, and law enforcement, and survivors whom Human Rights Watch interviewed described being told that it was not a serious crime because they were not physically injured and because it “only happened online.” These views represent a profound misunderstanding of the impact of technology-facilitated GBV. Once an image has been shared, even a single time, even briefly, the survivor will never be safe again from that image being shared. Any internet user who had access to the image could have taken a screen shot and could repost it at any time for the rest of the survivor’s life, harming the employment, education, reputation, and social and family relationships of the people targeted. Survivors described experiencing deep trauma, including deciding they had to leave the country, deciding to never again have a romantic relationship, withdrawing from online and other social life, and, frequently, considering suicide. There is a growing list of cases where victims of technology-facilitated GBV have died by suicide.

- Human Rights Watch’s research in South Korea and findings from other parts of the world shows that governments and companies are not meeting their respective responsibilities in tackling online gender-based violence, and this is causing widespread harm. Most countries need to update their laws to include this category of abuses in legislation protecting victims and holding accountable perpetrators of gender-based violence. Every country’s plan to address gender-based violence should include strategies to deal with technology-facilitated GBV, and take into account the fact that technology-facilitated GBV often occurs in cases involving other forms of intimate partner violence, stalking, and harassment. The law should recognize these abuses as crimes, set penalties for perpetrators proportionate to their culpability and the gravity of the offense (taking into account its impact on victims), require perpetrators and platforms to swiftly remove non-consensual intimate content, and give survivors access to effective civil remedies.

- Law enforcement actors are generally poorly equipped to handle these cases. They need the skills and resources to investigate and prosecute these cases, and training and accountability sufficient to ensure that they take these cases seriously, respect the rights—including the privacy rights—of survivors and avoid re-traumatization.

- Survivors need services, and these services are rarely available. They need urgent access to psychosocial support; legal assistance and advice; and help demanding that internet platforms block and remove non-consensual images. Internet platforms have a crucial role to play in assisting survivors and cooperating with law enforcement, but our research suggests that they often have complex and overly narrow policies on blocking and removing images, and ignore or refuse requests for assistance from law enforcement.

- Most fundamentally, social attitudes toward technology-facilitated GBV need to change. Gender inequality and harmful ideas about masculinity make some perpetrators feel that sharing and consuming non-consensual images is acceptable and even admired behavior. The most effective way to change this misconception is through comprehensive sexuality education for every student in every school, including a strong focus on consent and responsible digital citizenship.

- The violation of the right to privacy extends beyond the non-consensual filming and circulation. As the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy noted following his visit to South Korea in 2019, deletion support is an important element of a rights-based response to technology-facilitated GBV.[53] The right to privacy also applies to the justice process. The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, which interprets the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) has also stated that states parties are obligated to protect women’s and girls’ privacy throughout the judicial process, including by limiting who has access to testimony and evidence, the use of pseudonyms, and holding proceedings privately.[54]

- The CEDAW Committee and Special Rapporteurs on the promotion of freedom of expression and violence against women have identified private companies–including internet platforms–as essential partners for eliminating online gender-based violence. This includes helping fulfill state obligations to provide survivors transparent and fast responses and effective remedies, such as content deletion in a timely manner.[55]

- To protect children’s right to privacy, including their right to live free from technology-facilitated GBV, it is essential that governments work beyond the justice system to combat the deep gender inequality that normalizes gender-based violence.[56]

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Urge governments to enact laws or update existing laws, to address and provide effective remedies for technology-facilitated GBV and specifically consider consent, including around circulation of images, and to ensure that law enforcement authorities have the resources, expertise, and accountability to ensure that they handle technology-facilitated GBV appropriately.

Urge governments to provide all survivors of technology-facilitated GBV with psychosocial support, legal assistance, and assistance removing images from the internet.

Urge governments to make mandatory in national curriculums comprehensive sexuality education that teaches children—and parents—about consent and digital citizenship.

Urge private companies to meet their responsibilities under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights to work with survivors and governments to block and delete non-consensual intimate images in a timely manner, and cooperate with law enforcement, in accordance with due process rights, in all investigations of technology-facilitated GBV.

Child Data Privacy in Online Education Services

- The educational disruption caused by Covid-19 is unprecedented in speed and scale. By April 1, 2020, 193 countries had closed schools in an attempt to curb the pandemic’s spread. Education authorities rushed to move millions of children to online learning, where access to the internet and technology made it possible.[57]

- Education technology companies (“EdTech”) subsequently experienced explosive growth in demand and new users, thanks in part to international organizations and governments rapidly signing agreements with EdTech firms and recommending their products to schools and teachers. In March, after Covid-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, education app downloads worldwide surged 90 percent compared to the weekly average at the end of 2019.[58] For example, Byju’s, an Indian EdTech company, added 20 million new users in the first four months of the pandemic and became the first EdTech company to join the ranks of some two dozen private companies worldwide valued at US$10 billion or more.[59]

- This has also meant that EdTech is collecting vast, unprecedented amounts of children’s personal data. But because most countries do not have data privacy laws that protect children, much of this data—including names, home addresses, behaviors, and other highly personal details that can harm children and families when misused—remain unprotected, putting children’s privacy rights at risk.

- Human Rights Watch has found that many EdTech products recommended by governments and used by millions of children are problematic in how they collect, store, and use children’s data; with whom they share this data; and how they protect children’s privacy.[60]

- The sale or sharing of children’s data to third-party providers poses specific risks to children’s privacy. In September, the International Digital Accountability Council analyzed 496 EdTech apps across 22 countries and found privacy issues.[61] Several apps were found to be recording and sending location data to third-party advertisers, or collecting device identifiers that cannot be reset unless a new device is purchased. The researchers noted, “Location tracking–whether through collecting location or persistent identifiers–is particularly problematic when the data subjects are children. Collecting this information and sharing with third-parties allows for the possibility that this information will be manipulated, misused, or monetized.” [62]

- Several governments have waived existing child data privacy laws during Covid-19, arguing that such safeguards impede the shift to online learning. In Wales, the government waived the requirement for parents’ and students’ consent; in the United States, the governor of Connecticut suspended similar requirements under the Student Data Privacy Act.[63]

- Children exercising their right to education should not be compelled to give up their right to safety and privacy to do so, both in online and in physical spaces. Framing children’s privacy safeguards as an impediment to learning is false and potentially harmful, particularly as students’ data and their privacy are at heightened risk during this time. The pandemic has triggered a dramatic increase in cyberattacks seeking to acquire and demand ransom for students’ personal data. Education has now become the sector most affected worldwide by cyberattacks; Microsoft reported 5.7 million malware incidents on users of its education software between August 24 and September 24, 2020.[64]

- In interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch with students, parents, teachers, and education officials in 55 countries between April and August 2020, teachers worried about their students’ privacy, particularly those at risk. In the United States, one teacher in Iowa said, “Especially with undocumented students … I don’t know if they even fully know their rights or what being on the internet exposes them to, as far as their information.”[65] Another teacher in Texas said: “Teachers were using [an online platform] which has no privacy protection. I was worried because, especially for our kids, this is not safe for them. From 60 to 70 percent of our kids had one primary family member that had been deported or was currently in ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] holding. This is unacceptable, and it is a dangerous situation to put these kids in.”[66]

- Products adopted now–and the data they collect–may long outlast the current crisis.

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Urge states to perform due diligence to ensure that the technology they recommend for online learning protects children’s privacy rights.

Urge states to provide guidance to schools on the inclusion of data privacy clauses in contracts signed with EdTech providers, to protect the data collected on children during this time from misuse.

Urge states with existing child data protection laws not to waive them, and for states without such laws to institute data protection laws for children.

Urge EdTech companies to protect children’s privacy at all stages of the data lifecycle, and to provide children with the choice of meaningfully opting out of the collection of their data, as well as to enable them to delete their data.

Children's Privacy in Criminal Proceedings

- Under international human rights law, every child alleged to have committed a crime is guaranteed to have their privacy fully respected at all stages of the proceedings.[67] International standards provide that no information should be published that may lead to the identification of the child.[68] Countries around the world have established special protections to safeguard these rights, including in Argentina, where the police and courts are prohibited from publishing information that may identify a child accused of a crime.[69]

- However, Argentina’s Justice and Human Rights Ministry has regularly published online the personal data of children with open arrest warrants, in violation of international obligations to respect children’s privacy in criminal proceedings. The Buenos Aires city government has then been loading the images and identities of these children into a facial recognition system used at the city’s train stations, despite significant errors in the national government’s database and the technology’s higher risk of false matches for children.

- Since 2009, the Justice and Human Rights Ministry has maintained a national database of people with outstanding arrest warrants, known as the National Register of Fugitives and Arrests (Consulta Nacional de Rebeldías y Capturas, CONARC).[70]

- On May 17, 2019, the Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy warned the Argentinean government that its use of CONARC was violating children’s rights.[71] The rapporteur found that the database, which the ministry makes publicly available online, contained 61 children and their personally identifiable information.

- Human Rights Watch found that at least 166 children were listed in CONARC between May 2017 and May 2020, at least 25 of whom were added after the Special Rapporteur’s warning. Even children suspected of minor crimes are included. Persistent errors and obvious discrepancies in CONARC indicate that the system lacks basic safeguards to minimize data entry errors, which can have serious consequences for a child’s reputation and safety.

- These harms have been amplified in the City of Buenos Aires. Since April 24, 2019, the city government of Buenos Aires has fed the CONARC data—including its data on children—into its facial recognition system, the Fugitive Facial Recognition System (Sistema de Reconocimiento Facial de Prófugos).[72] The technology scrutinizes live video feeds of people catching a subway train or walking through or in the vicinity of a subway station, and identifies possible matches with the identities in CONARC.

- This practice is particularly problematic when it comes to children. Facial recognition technology has considerably higher error rates for children, in part because most algorithms have been trained, tested, and tuned only on adult faces. In addition, since children experience rapid and drastic changes in their facial features as they age, facial recognition algorithms also often fail to identify a child who is a year or two older than in a reference photo. Because the facial recognition system matches live video with identity card photos collected by the country’s population registry, which are not guaranteed to be recent, it may be making comparisons with outdated images of children, further increasing the error rate.

- Error rates also substantially increase when facial recognition is deployed in public spaces where the images captured on video surveillance cameras are natural, blurred, and unposed. Deploying this technology in Buenos Aires’ subway system, with a daily ridership of over 1.4 million people and countless more passing through or near its stations, will result in people being wrongly flagged as suspects for arrest. These concerns are amplified by the practices of the Buenos Aires police, who are stopping and detaining people solely on the basis of the automated alerts generated by the facial recognition system. Adults have been mistakenly detained and arrested.

- Human Rights Watch is concerned by the absence of public or legislative debate around the necessity and proportionality of Buenos Aires City’s facial recognition system, especially considering the technology’s adverse impacts on children.[73]

- We recommend that the Special Rapporteur:

Urge governments to ensure protections for the privacy of children accused of committing a crime.

Urge governments to adopt strong child data protection laws that meaningfully regulate the collection, processing, use, and sharing of children’s personal data, and to strengthen child-specific data privacy measures in existing national data protection laws.

Urge governments that are considering linking civil and criminal identity databases to first conduct a privacy and human rights impact assessment, publish an evidence-based rationale of the link between the means and the ends, and invite engagement with the public and with lawmakers to assess the necessity, proportionality, and legality of biometric surveillance infrastructure, with special consideration for its implications for children and their privacy.

Annex

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic has the highest teen pregnancy rate in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).[74]

Abortion is illegal in all circumstances in the Dominican Republic, even when the life of the pregnant person is in danger. Human Rights Watch research published in a 2018 report found the country’s total abortion ban had devastating consequences.[75] People facing unplanned or unwanted pregnancies—including those resulting from rape or incest, or when the fetus will not survive—were often forced to choose between unsafe abortion or continuing their pregnancies, even if they did not want to and even if they faced serious health risks, including death. Some people couldn’t afford to travel to another country where abortion is legal or find safe providers to help them to end a pregnancy, but many, especially people living in poverty or in rural communities, risked their health and lives to have abortions, often without any guidance from trained providers. Some suffered serious health complications, and even death, from unsafe abortion.

The death of 16-year-old Rosaura Almonte Hernández in 2012 illustrates the impact of the country’s criminal laws that block access to abortion to protect the health of the pregnant person. Rosaura, known as “Esperancita,” was diagnosed with leukemia, but she was initially denied access to chemotherapy because she was seven weeks pregnant. Her mother requested access to therapeutic abortion, and her request was denied. Weeks later, under mounting international pressure, doctors provided Esperancita with chemotherapy, but she died in August 2012. In 2017, her mother, Rosa Hernández, with support from the organizations Women’s Link Worldwide and Colectiva Mujer y Salud filed a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) seeking justice for her daughter’s death.[76] In 2020, the IACHR announced that it had admitted the case for review.[77]

El Salvador

Criminalization of abortion in El Salvador—where abortion has been illegal under all circumstances since 1997—also demonstrates the human cost of a restrictive environment.[78] Providers and those who assist face prison sentences of six months to 12 years.[79] Dozens of girls and women, mostly from high-poverty areas, were prosecuted in the past two decades for what lawyers and activists say were obstetric emergencies.[80] In some cases, the courts accepted as evidence a questionable autopsy procedure known as the “floating lung” test to forensically support the claim that a fetus was delivered alive.[81] As of September 2020, 19 women who said they suffered obstetric emergencies remained imprisoned on charges of abortion, homicide, or aggravated homicide.[82] At least 16 of them had been convicted of aggravated homicide.

Brazil

Abortion is a crime in Brazil, except in cases of rape, when the life of the pregnant person is at risk, or the fetus has anencephaly. Human Rights Watch has documented the devastating consequences of Brazil’s severe abortion restriction.[83] In August 2020, a 10-year-old-girl in Espírito Santo State discovered she was pregnant after four years of repeated rape by her uncle, who threatened her to keep quiet.[84] The girl wanted to end the pregnancy and under Brazilian law, she had the right to do so. However, the hospital where she was admitted refused to perform the abortion, alleging it did not have the authority to conduct the procedure. Meanwhile, Brazil’s government allegedly sent a delegation to try to prevent the girl from having an abortion.[85] A judge intervened and granted the girl legal permission to terminate the pregnancy. Following the ruling, an anti-abortion activist published the girl’s name and the name of the hospital, 900-miles from her home, where she would have the procedure and anti-abortion protesters blocked access to the hospital and harassed and insulted its personnel. The girl finally had an abortion on August 17.

Even in the very limited cases in which the termination of a pregnancy is legal is Brazil, access to abortion can be very difficult.[86] In a country of 210 million people, only 42 hospitals are performing legal abortions during the Covid-19 pandemic, according to a study by the nongovernmental group Article 19 and the news websites AzMina and Gênero e Número.[87] In 2019, it was 76 hospitals.

In August, the Health Ministry issued a regulation that erects new barriers to legal abortion access and could discourage women and girls from seeking medical care. Among other measures, the regulation requires medical personnel to report to the police anyone who seeks legal termination of a pregnancy after rape, regardless of the rape survivor’s wishes.[88] The Ministry of Family, Women, and Human Rights has also announced the creation of a hotline for medical personnel that could be used to report women and girls whom they suspect had an illegal abortion, for possible prosecution.

Honduras

Abortion in Honduras is illegal in all circumstances, including rape and incest, when a pregnant person’s life is in danger, and when the fetus cannot survive outside the womb. The country’s criminal code imposes prison sentences of up to six years on women and girls who induce abortions and on medical professionals who provide them.[89] The government also bans emergency contraception, or the “morning after pill,” which can prevent pregnancy after rape, unprotected sex, or a contraceptive failure.[90]

In 2017, 820 girls ages 10 to 14 gave birth in Honduras, according to data from the health secretary. Many of these girls became pregnant from statutory rape under Honduran law, which establishes that 14 is the age of sexual consent. A social worker at a women’s rights organization that helps survivors of violence told Human Rights Watch she has counseled girls who were 16, 15, or even 12 years old who became pregnant as a result of incest or rape and were forced to continue their pregnancy. “To have to continue with an unwanted pregnancy that resulted from abuse, it’s almost torture,” she said.

Women interviewed by Human Rights Watch in 2019 said they tried to end unwanted pregnancies using the medication misoprostol and in unsafe clinics with untrained providers. Several sought emergency treatment at hospitals afterward for complications such as uncontrolled bleeding or intense pain. Data from the Honduras health secretary show more than 8,600 women were hospitalized for complications from abortion or miscarriage in 2017.[91]

Reliable research shows that restrictive laws and criminal penalties do not reduce the incidence of abortion.[92] One Honduran nongovernmental organization estimated that 50,000 to 80,000 abortions occur in the country every year. The country’s total ban on abortion in all circumstances puts pregnant people in danger and violates their rights to life, to health, and not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.

Ecuador

Across Ecuador, criminalization of abortion is having a devastating impact on the lives and health of people who seek abortions, face obstetric emergencies mistakenly attributed to abortion, or need post-abortion medical care or care during a miscarriage. [93] Pregnant people face many barriers to accessing legal abortion and post abortion care, including criminal prosecution, stigmatization and mistreatment according to recent research conducted by Human Rights Watch.

On August 25, the National Assembly approved a new Health Code that would have prohibited delaying emergency health care—including legal abortion—for any reason, including conscientious objection, and reiterated the duty of healthcare professionals to respect medical confidentiality, including in cases of an obstetric emergency.[94] On September 25, 2020, President Moreno vetoed the bill. [95]

Ecuadorian law imposes prison terms ranging from six months to two years for people who receive abortions or induce abortions, and from one to three years for health providers who perform an abortion found to be prohibited by law when it was done with the pregnant person’s consent.[96] When the abortion is conducted without the pregnant person’s consent, the law imposes prison terms ranging from five to seven years. At least 120 people have been prosecuted in Ecuador from 2009-2019 for abortion, according to Human Rights Watch research.

Abortion is legally permitted in Ecuador in cases where the pregnant person's life or health is in danger, or the pregnant person is a person with a mental health condition who has been raped.

However, the law is interpreted very narrowly and pregnant people face many barriers to accessing legal abortion and post abortion care. Based on research conducted in Ecuador, Human Rights Watch concluded that fear of facing prosecution has encouraged doctors and healthcare workers—including both those treating patients and those in more administrative roles—to be quick to turn in their patients, violating their own professional obligations and their patients’ rights to confidentiality and privacy. Many hospitals base these policies on articles 276 and 422 of the Criminal Code, which criminalizes health workers’ failure to report a crime.[97] However, the Constitution protects doctor-patient confidentiality, and the Criminal Code establishes that the obligation to report does not apply to such confidential communications.[98]

In our research, Human Rights Watch found that young women living in poverty and belonging to marginalized ethnic groups are less likely to have access to the information and resources necessary to find safe abortion services. They are also less likely to have information about the law on abortion and the steps necessary to access legal abortion. Rosa, an 18-year-old mestiza young woman, arrived at an emergency room in 2015 with an incomplete abortion. She was twelve and a half weeks pregnant. The judge sentenced her to 60 days in prison for consensual abortion and told her she had "killed the one who lived inside your womb, which in a few words means to murder.”[99]

Although Ecuador has high rates of sexual violence, rape victims (other than those with a mental health condition), including children under 18, are denied legal access to a therapeutic abortion and are often prosecuted when they manage to access abortion.[100] The National Assembly, in 2019, rejected a proposal to decriminalize abortion in other cases of rape.[101]

[1] Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), General Comment No. 20 on the implementation of the rights of the child during adolescence (2016), https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CRC/GC_adolescents.doc (accessed September 29, 2020), para. 64.

[2] See, for example, CRC concluding observations on Poland, UN Doc. E/C.12/POL/CO/6 (2016); Indonesia, UN Doc. CRC/C/IDN/CO/3-4 (2014); Venezuela, UN Doc. CRC/C/VEN/CO/3-5 (2014); and Morocco, UN Doc. CRC/C/MAR/CO/3-4 (2014).

[3] See, for example, CRC concluding observations on Sri Lanka, UN Doc. CRC/C/LKA/CO/5-6 (2018); and India, UN Doc. CRC/C/IND/CO/3-4 (2014).

[4] Center for Reproductive Rights, Capacity and Consent: Empowering adolescents to exercise their reproductive rights, 2017, https://www.reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/GA-Adolescents-FINAL.pdf (accessed September 22, 2020), p. 4.

[5] Cook R, Dickens BM, “Recognizing adolescents' 'evolving capacities' to exercise choice in reproductive healthcare,” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, July 2000, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10884530/ (accessed September 22, 2020).

[6] See UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/RES/1990/74, March 1990, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (accessed September 29, 2020), art. 12. UN Committee against Torture (CAT Committee), Concluding Observations: Greece, para. 6(m), U.N. Doc. CAT/C/CR/33/2 (2004) (“All decisions affecting children should, to the extent possible, be taken with due consideration for their views and concerns, with a view to finding an optimal, workable solution”); Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, Rep. of the Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, Najat M’jid Maalla–Addendum–Mission to Latvia, para. 84(c), U.N. Doc. A/ HRC/12/23/Add.1 (2009) (“The participation of children should be strengthened on all issues concerning them, and their views should be given due weight”). Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 12: The Right of the child to be heard, (51st Sess., 2009), paras. 2, 17, U.N. Doc. CRC/C/GC/12 (2009).

[7] CRC Committee, Concluding Observations: India, para. 66(b), U.N. Doc. CRC/C/IND/CO/7-8 (2014) & CRC Committee, Concluding Observation: Jordan, para. 46, U.N. Doc. CRC/C/JOR/CO/4-5 (2014).

[8] See United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), “Adolescence, An Age of Opportunity,” February 2011, https://www.unicef.org/sowc2011/pdfs/SOWC-2011-Main-Report_EN_02092011.pdf (accessed September 29, 2020).

[9] CRC Committee, Concluding Observations: Namibia, para. 57(a), U.N. Doc. CRC/C/NAM/CO/2-3 (2012); (“The State party’s punitive abortion law and various social and legal challenges, including long delays in accessing abortion services within the ambit of the current laws for pregnant girls. In this regard, the Committee notes with concern that such a restrictive abortion law has led adolescents to abandon their infants or terminate pregnancies under illegal and unsafe conditions, putting their lives and health at risk, which violates their rights to life, to freedom from discrimination, and to health”).

[10] Singh S et al., Abortion Worldwide 2017: Uneven Progress and Unequal Access, Guttmacher Institute, 2018, https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/abortion-worldwide-2017.pdf (accessed September 24, 2020), p. 10. Ibid., p. 33.

[11] Ibid.

[12] See, for example, CESCR concluding observations on Slovakia, UN Doc. E/C.12/SVK/CO/2 (2012), para. 24 https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=E%2fC.12%2fSVK%2fCO%2f2&Lang=en (accessed September 29, 2020).

[13] Ibid.; Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) concluding observations on El Salvador, UN Doc. CRC/C/SLV/CO/5-6 (2018), https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRC/C/SLV/CO/5-6&Lang=En (accessed September 29, 2020), para. 35.

[14] See, for example, CAT Committee, concluding observations on Paraguay, UN Doc. CAT/C/PRY/CO/4-6 (2011), https://www.atlas-of-torture.org/en/document/wgc9npwq5oqbwn0115ib2o6r (accessed September 29, 2020); CAT Committee concluding observations on Peru, UN Doc. CAT/C/PER/CO/5-6 (2013), https://www.atlas-of-torture.org/en/document/ox69in6s8y7cw9zwrw32wewmi?page=1 (accessed September 29, 2020); Human Rights Committee (HRC) concluding observations on El Salvador, UN Doc. CCPR/C/SLV/CO/7 (2018), https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2fC%2fSLV%2fCO%2f7&Lang=en (accessed September 29, 2020).

[15] Paulina del Carmen Ramírez Jacinto v. Mexico, Friendly settlement, Petition 161-02, Inter-Am. Comm’n H.R., Report No. 21/07, OEA/Ser.L/V/II.130, doc.22 rev.1 (2007).

[16] See, for example, Center for Reproductive Rights, Innovative litigation filed against three countries to protect girls’ rights in Latin America, 2019, https://reproductiverights.org/press-room/innovative-litigation-filed-against-three-countries-to-protect-girls’-rights-in-latin-ame (accessed September 22, 2020).

[17] UN Women, Facts and figures: Ending violence against women, November 2019, https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures (accessed September 22, 2020).

[18] UNICEF, The path to girls’ empowerment in Latin America and the Caribbean: 5 rights, October 2017, https://www.unicef.org/lac/media/1441/file/PDF%20El%20camino%20al%20empoderamiento%20de%20las%20niñas%20en%20América%20Latina%20y%20el%20Caribe%3A.pdf (accessed September 22, 2020), p. 6.

[19] Center for Reproductive Rights, They are girls: Reproductive rights violations in Latin America and the Caribbean, May 2019, https://reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/documents/20190523-GLP-LAC-ElGolpe-FS-A4.pdf (accessed September 22, 2020).

[20] Ibid.

[21] See Annex.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence, The Adolescent’s Right to Confidential Care When Considering Abortion, 2017, https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/139/2/e20163861 (accessed September 24, 2020); Stanley K. Henshaw and Kathryn Kost, “Parental Involvement in Minors’ Abortion Decisions,” Family Planning Perspectives, September 1992, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kathryn_Kost/publication/21729897_Parental_Involvement_in_Minors%27_Abortion_Decisions/links/54d4e6380cf25013d02a1fbc/Parental-Involvement-in-Minors-Abortion-Decisions.pdf (accessed September 24, 2020); Zabin LS, Hirsch MB, Emerson MR, Raymond E., “To whom do inner-city minors talk about their pregnancies? Adolescents' communication with parents and parent surrogates,” Family Planning Perspectives, 1992, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1526270/ (accessed September 24, 2020); Hasselbacher LA, Dekleva A, Tristan S, Gilliam ML, “Factors influencing parental involvement among minors seeking an abortion: a qualitative study,” American Journal of Public Health, November 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4202942/ (accessed September 24, 2020).

[27] Lawrence B. Finer, et al., “Timing of steps and reasons for delays in obtaining abortions in the United States,” Contraception, vol. 74 (2006), June 2006, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16982236/ (accessed September 29, 2020), pp. 334-344.

[28] Letter from Human Rights Watch to Senator David Simmons, Chair of the Florida Senate Judiciary Committee, “Letter to Urge Florida Senate to Reject Forced Parental Consent for Abortion,” January 14, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/01/14/letter-urge-florida-senate-reject-forced-parental-consent-abortion#

[29] See International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, art. 19(2); American Convention on Human Rights, (“Pact of San José”), adopted November 22, 1969, O.A.S. Treaty Series No. 36, 1144 U.N.T.S. 123, entered into force July 18, 1978, art. 13(1).

[30] See International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, article 2(2). See also CESCR General Comment No. 14 on the right to the highest attainable standard of health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000); and CESCR General Comment No. 22 on the right to sexual and reproductive health, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/22 (2016).

[31] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has recommended that states adopt “[a]ge-appropriate, comprehensive and inclusive sexual and reproductive health education, based on scientific evidence and human rights standards and developed with adolescents, [as] part of the mandatory school curriculum and reach out-of-school adolescents. Attention should be given to gender equality, sexual diversity, sexual and reproductive health rights, responsible parenthood and sexual behaviour and violence prevention, as well as to preventing early pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.” Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 20 (2016) on the implementation of the rights of the child during adolescence, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/20 (2016), https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRC%2fC%2fGC%2f20&Lang=en (accessed September 29, 2020), para. 61; Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 22 on the right to sexual and reproductive health, UN Doc. E/C.12/GC/22 (2016), https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=E%2fC.12%2fGC%2f22&Lang=en (accessed September 29, 2020), para. 9.

[32] Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 20 (2016) on the Implementation of the Rights of the Child During Adolescence, para. 59.

[33] See, for example, Dom Phillips, “’Like going back 40 years’: dismay as Bolsonaro backs abstinence-only sex ed,” Guardian, January 17, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/17/brazil-bolsonaro-backs-abstinence-only-sex-education?CMP=share_btn_tw (accessed September 24, 2020).

[34] See, for example, Dahia Sena, “Victor Masalles asegura ordenanza del Minerd pretende desprogramar la raza humana,” CDN, June 6, 2019, https://cdn.com.do/2019/06/06/victor-masalles-asegura-ordenanza-del-minerd-pretende-desprogramar-la-raza-humana/ (accessed September 24, 2020).

[35] See, for example, “Here’s why Ghana’s sex education program is controversial,” Africa News, March 10, 2020, https://www.africanews.com/2019/10/03/here-s-why-ghana-s-sex-education-program-is-controversial// (accessed September 24, 2020).

[36] See, for example, David Oginde, “Why the church opposes bid to introduce sex education,” The Standard, January 21, 2018, https://standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001266642/why-the-church-opposes-bid-to-introduce-sex-education (accessed September 24, 2020).

[37] See, for example, “Polish Parliament Should Scrap Bill Against Sex Education,” Human Rights Watch news release, October 18, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/10/18/polish-parliament-should-scrap-bill-against-sex-education

[38] Human Rights Watch, “It Wasn’t Really Safety, It Was Shame”: Young People, Sexual Health Education, and HPV in Alabama, July 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/07/08/it-wasnt-really-safety-it-was-shame/young-people-sexual-health-education-and-hpv

[39] Ibid.

[40] Human Rights Watch, Leave No Girl Behind in Africa: Discrimination in Education against Pregnant Girls and Adolescent Mothers, June 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/06/14/leave-no-girl-behind-africa/discrimination-education-against-pregnant-girls-and

[41] Human Rights Watch, “I Had a Dream to Finish School”: Barriers to Secondary Education in Tanzania, February 2017, https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/02/14/i-had-dream-finish-school/barriers-secondary-education-tanzania#7406

[42] Ibid.

[43] International Development Research Centre, “Les Médias au Sénégal: Outil de Sensibilisation ou de Banalisation des VBG?” March 2014, https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/123456789/10126/Les%20m%C3%A9dias%20au%20S%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal%20outils%20de%20sensibilisation%20ou%20de%20banlisation%20des%20VBG%20au%20S%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.pdf?sequence=3 (accessed February 18, 2018).

[44] Human Rights Watch, “It’s Not Normal”: Sexual Exploitation, Harassment and Abuse in Secondary Schools in Senegal, October 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/10/18/its-not-normal/sexual-exploitation-harassment-and-abuse-secondary-schools-senegal#_ftn93

[45] Human Rights Watch, “Like Walking Through a Hailstorm”: Discrimination Against LGBT Youth in US Schools, December 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/12/08/walking-through-hailstorm/discrimination-against-lgbt-youth-us-schools; Human Rights Watch interview with Minhee Ryu, Korean Lawyers for Public Interest Law, Seoul, March 10, 2019.

[46] Human Rights Watch, Shut Out: Restrictions on Bathroom and Locker Room Access for Transgender Youth in US Schools, September 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/09/14/shut-out/restrictions-bathroom-and-locker-room-access-transgender-youth-us; Human Rights Watch, “Like Walking Through a Hailstorm”: Discrimination Against LGBT Youth in US Schools, December 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/12/08/walking-through-hailstorm/discrimination-against-lgbt-youth-us-schools

[47] Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted December 10, 1948, G.A. Res. 217A(III), U.N. Doc. A/810 at 71 (1948), art. 12; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, art. 17; and Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), adopted November 20, 1989, G.A. Res. 44/25, annex, 44 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 49) at 167, U.N. Doc. A/44/49 (1989), entered into force September 2, 1990, art. 8.

[48] UN General Assembly, The right to privacy in the digital age, U.N. Doc. A/RES/71/199 (2017), 5(g). UN Human Rights Council, The right to privacy in the digital age, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/42/15 (2019), 6(h).

[49] UN Human Rights Council, Accelerating efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls: preventing and responding to violence against women and girls in digital contexts, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/38/5 (2018), para. 3.

[50] Sentencing Advisory Council, “Image-Based Sexual Abuse,” 2019, https://www.sentencingcouncil.vic.gov.au/projects/image-based-sexual-abuse (accessed October 6, 2020); The Association for Progressive Communications (APC), EROTICS Global Survey 2017: Sexuality, rights and internet regulations, 2017, https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/Erotics_2_FIND-2.pdf (accessed October 6, 2020).

[51] Human Rights Watch interview with Hawon Jung, Former Journalist with Agence France-Presse, Seoul, Korea, September 18, 2019.

[52] Erika Nguyen, “South Korea Online Sexual Abuse Case Illustrates Gaps in Government Response,” commentary, Human Rights Watch dispatch, March 26, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/26/south-korea-online-sexual-abuse-case-illustrates-gaps-government-response

[53] “Statement to the media by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy, on the conclusion of his official visit to the Republic of Korea, 15-26 July 2019,” UN Special rapporteur statement, July 26, 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24860&LangID=E (accessed September 11, 2020).

[54] CEDAW Committee, General Recommendation No. 33 on Women’s Access to Justice, U.N. Doc. CEDAW/C/GC/33 (August 3, 2015).

[55] Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences on online violence against women and girls from a human rights perspective, para. 52.

[56] CEDAW Committee, General Recommendation No. 35 on Gender-Based Violence against Women, U.N. Doc. CEDAW/C/GC/35 (July 26, 2017); and UN General Assembly, The right to privacy in the digital age, U.N. Doc. A/RES/71/199 (2017), 5(g).

[57] See UNESCO, “Education: From disruption to recovery,” n.d., https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed September 24, 2020).

[58] Karen Gilchrist, “These millennials are reinventing the multibillion-dollar education industry during coronavirus,” CNBC, June 8, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/08/edtech-how-schools-education-industry-is-changing-under-coronavirus.html (accessed September 24, 2020); Lexi Sydow, “Mobile Minute: Global Classrooms Rely on Education Apps As Remote Learning Accelerates,” App Annie blog post, April 8, 2020, https://www.appannie.com/en/insights/mobile-minute/education-apps-grow-remote-learning-coronavirus/ (accessed September 24, 2020).

[59] Neha Dewan, “How Covid led Byju’s to add 20 million new users in less than four months,” Economic Times, August 7, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/newsbuzz/how-covid-led-byjus-to-add-20-million-new-users-in-less-than-four-months/articleshow/77408672.cms (accessed September 24, 2020); Manish Singh, “Mary Meeker’s Bond backs Indian online learning startup Byju’s, Tech Crunch, June 26, 2020, https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/25/mary-meekers-bond-invests-in-indian-online-learning-giant-byjus/ (accessed September 24, 2020); “The Global Unicorn Club,” CB Insights, September 2020, https://www.cbinsights.com/research-unicorn-companies (accessed September 24, 2020).

[60] Hye Jung Han, “As Schools Close Over Coronavirus, Protect Kids’ Privacy in Online Learning,” commentary, Human Rights Watch dispatch, March 27, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/27/schools-close-over-coronavirus-protect-kids-privacy-online-learning

[61] International Digital Accountability Council (IDAC), Privacy Considerations as Schools and Parents Expand Utilization of Ed Tech Apps During the COVID-19 Pandemic, September 1, 2020, https://digitalwatchdog.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/IDAC-Ed-Tech-Report-912020.pdf (accessed September 24, 2020).

[62] Ibid.

[63] Welsch Government Digital Learning for Wales press release, “Hwb Additional Services for EVERY learner,” March 20, 2020, https://hwb.gov.wales/news/article/76979aea-3819-42e9-9c10-121e907ef922 (accessed September 24, 2020); State of Connecticut Executive Order No. 71, Protection of Public Health and Safety During Covid-19 Pandemic and Response–Municipal Operations and Availability of Assistance and Healthcare, March 10, 2020, https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/Office-of-the-Governor/Executive-Orders/Lamont-Executive-Orders/Executive-Order-No-7I.pdf#page=6 (accessed September 24, 2020).

[64] See Microsoft, “Global threat activity,” September 2020, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/wdsi/threats (accessed September 24, 2020).

[65] Human Rights Watch interview with teacher, central Iowa, United States, June 18, 2020.

[66] Human Rights Watch interview with teacher, Dallas, Texas, United States, June 8, 2020.

[67] Convention on the Rights of the Child, September 2, 1990, ratified by Argentina December 4, 1990, arts. 16 & 40(2)(b)(vii).

[68] United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (“The Beijing Rules”), adopted by General Assembly resolution 40/33, November 29, 1985, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/beijingrules.pdf (accessed May 22, 2020), art. 8.

[69] See “Directive (EU) 2016/800 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on procedural safeguards for children who are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings,” Official Journal of the European Union, May 21, 2016, http://db.eurocrim.org/db/en/doc/2500.pdf (accessed May 22, 2020), art. 14; Government of Argentina, State Party Report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, CRC/C/8/Add.17, December 22, 1994, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6af730.html (accessed May 22, 2020), para. 191.

[70] Resolución 1068 - E/2016, approved November 10, 2016, http://www.vocesporlajusticia.gob.ar/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/res10682016mj.pdf (accessed May 22, 2020)

[71] Statement to the media by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy, on the conclusion of his official visit to Argentina, 6-17 May 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24639&LangID=E (accessed May 22, 2020)

[72] Resolución 398/MJYSGC/19, approved April 24, 2019, https://documentosboletinoficial.buenosaires.gob.ar/publico/ck_PE-RES-MJYSGC-MJYSGC-398-19-5604.pdf (accessed May 27, 2020)

[73] The municipal government accelerated passage of the legislation that enabled the adoption of the SRFP, passing it as a resolution rather than a law and bypassing public debate. See Resolución 398/MJYSGC/19, approved April 24, 2019, https://documentosboletinoficial.buenosaires.gob.ar/publico/ck_PE-RES-MJYSGC-MJYSGC-398-19-5604.pdf (accessed June 12, 2020) and Dave Gershgorn, “The U.S. Fears Live Facial Recognition. In Buenos Aires, It’s a Fact of Life,” March 4, 2020, https://onezero.medium.com/the-u-s-fears-live-facial-recognition-in-buenos-aires-its-a-fact-of-life-52019eff454d (accessed June 2, 2020).

[74] The adolescent fertility rate, defined as the number of pregnancies per 1,000 girls and young women ages 15 to 19, was 96.1 in the Dominican Republic in 2017. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA), “Core Indicators, Indicator Profiles, Adolescent Fertility Rate (Births/1,000 women aged 15-19),” 2017, http://www.paho.org/data/index.php/en/indicators/visualization.html (accessed June 1, 2020).

[75] Human Rights Watch, “It’s Your Decision, It’s Your Life”: The Total Criminalization of Abortion in the Dominican Republic, November 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/11/19/its-your-decision-its-your-life/total-criminalization-abortion-dominican-republic (accessed September 29, 2020).

[76] Ibid.

[77] Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, Informe No. 67/20 Petición 1223-17: Informe de Admisibilidad, February 24, 2020, https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/decisiones/2020/rdad1223-17es.pdf (accessed October 6, 2020).

[78] Human Rights Watch, World Report 2020 (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2020), El Salvador chapter, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/el-salvador

[79] La Asamblea Legislativa de la República de El Salvador, Código Penal de El Salvador, No. 1030. Enacted June 15, 1974, http://www.oas.org/dil/esp/Codigo_Penal_El_Salvador.pdf (accessed October 6, 2020), arts. 134- 137.

[80] Karen Moreno, “El Salvador aún no acata exigencia de ONU para liberar a mujeres criminalizadas,” Revista GatoEncerrado, August 13, 2020, https://gatoencerrado.news/2020/08/13/el-salvador-aun-no-acata-exigencia-de-onu-para-liberar-a-mujeres-criminalizadas/ (accessed October 6, 2020).

[81] Peñas-Defago, M. Angélica, "Las 17.," Estrategias legales y políticas para legalizar el aborto en El Salvador. Rev. Bioética y Derecho, Barcelona , n. 43, 2018, http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1886-58872018000200008&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed October 6, 2020), pp. 91-107.

[82] Karen Moreno, “El Salvador aún no acata exigencia de ONU para liberar a mujeres criminalizadas,” Revista GatoEncerrado, August 13, 2020, https://gatoencerrado.news/2020/08/13/el-salvador-aun-no-acata-exigencia-de-onu-para-liberar-a-mujeres-criminalizadas/ (accessed October 6, 2020).

[83] Margaret Wurth, “No Woman Should Need to Beg for An Abortion,” commentary, Human Rights Watch op-ed, December 1, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/12/01/no-woman-should-need-beg-abortion

[84] Delphine Starr, “A 10-Year-Old Girl’s Ordeal to Have a Legal Abortion in Brazil,” commentary, Human Rights Watch dispatch, August 20, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/20/10-year-old-girls-ordeal-have-legal-abortion-brazil

[85] Carolina Vila-Nova, “Ministra Damares Alves agiu para impedir aborto em criança de 10 anos,” Folha de São Paulo, September 20, 2020, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2020/09/ministra-damares-alves-agiu-para-impedir-aborto-de-crianca-de-10-anos.shtml (accessed October 6, 2020).

[86] “Brazil: Revoke Regulation Curtailing Abortion Access,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 21, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/21/brazil-revoke-regulation-curtailing-abortion-access

[87] Article 19, “Atualização no Mapa Aborto Legal indica queda em hospitais que seguem realizando o serviço durante pandemia,” June 2, 2020, https://artigo19.org/blog/2020/06/02/atualizacao-no-mapa-aborto-legal-indica-queda-em-hospitais-que-seguem-realizando-o-servico-durante-pandemia/ (accessed October 6, 2020).

[88] “Brazil: Revoke Regulation Curtailing Abortion Access,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 21, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/21/brazil-revoke-regulation-curtailing-abortion-access

[89] Congreso Nacional de Honduras, Código Penal de Honduras, No. 144-83, September 26, 1983, https://www.oas.org/dil/esp/Codigo_Penal_Honduras.pdf (accessed October 6, 2020), arts. 126-128.

[90] See “Hablemos Lo Que Es: PAE,” n.d., https://hablemosloquees.com/ (accessed September 29, 2020).

[91] Human Rights Watch, Life or Death Choices for Women Living Under Honduras’ Abortion Ban, June 6, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/06/life-or-death-choices-women-living-under-honduras-abortion-ban

[92] Singh S et al., Abortion Worldwide 2017: Uneven Progress and Unequal Access, Guttmacher Institute, 2018, https://www.guttmacher.org/news-release/2018/new-report-highlights-worldwide-variations-abortion-incidence-and-safety (accessed October 6, 2020).

[93] De la Torre, V., Castello, P., & Cevallos, M. R., Vidas robadas: entre la omisión y la premeditación. Situación de la maternidad forzada en niñas del Ecuador, 2016, Quito: Fundación Desafío, http://repositorio.dpe.gob.ec/handle/39000/2410 (accessed October 7, 2020); Pulitzer Center, The Consequences of Ecuador's Abortion Ban, n.d., https://pulitzercenter.org/projects/consequences-ecuadors-abortion-ban (accessed October 7, 2020).

[94] “Asamblea Nacional aprueba el Código de la Salud que define la emergencia obstétrica, uso terapeútico del cannabis y reproducción humana asistida,” El Universo, August 25, 2020, https://www.eluniverso.com/noticias/2020/08/25/nota/7954558/asamblea-nacional-ecuador-codigo-organico-salud-aborto-cannabis (accessed October 6, 2020).

[95] Tweet by El Comercio, September 25, 2020, https://twitter.com/elcomerciocom/status/1309505853809143809 (accessed October 6, 2020).

[96] Asamblea Nacional de la República del Ecuador, Código Orgánico Integral Penal, Registro Oficial No. 180, February 10, 2014, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/ECU/INT_CEDAW_ARL_ECU_18950_S.pdf (accessed October 7, 2020), arts. 147-150.

[97] Ibid., arts. 276 & 422.

[98] Asamblea Nacional de la República del Ecuador, “Constitución del Ecuador,” October 20, 2008, https://www.asambleanacional.gob.ec/sites/default/files/documents/old/constitucion_de_bolsillo.pdf (accessed October 13, 2020).

[99] Case on file with Human Rights Watch.

[100] UN Women, Global Database on Violence against Women, 2016, https://evaw-global-database.unwomen.org/en/countries/americas/ecuador (accessed October 6, 2020).

[101] “Rechazan en Ecuador despenalizar el aborto por incesto o violación,” Deutsche Welle, September 18, 2019, https://www.dw.com/es/rechazan-en-ecuador-despenalizar-el-aborto-por-incesto-o-violaci%C3%B3n/a-50469438 (accessed October 6, 2020).