(Kyiv) – Russian authorities are conscripting males in occupied Crimea to serve in the Russian armed forces, Human Rights Watch said today. International humanitarian law explicitly forbids Russia from compelling Crimean residents to serve in its armed forces.

The authorities have imposed criminal penalties against those who refuse to comply with the draft, with the numbers of men punished rising over the years. Russia should immediately cease these practices, release Crimeans who have been forced to serve in the Russian forces and abide by its obligations as an occupying power.

“As an occupying power, Russia not only has no right to conscript people in Crimea, but its draft is blatantly violating international law,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Doubling down on this violation, Russian authorities are also pressing criminal charges against people who refuse to serve in its armed forces.”

Human Rights Watch reviewed dozens of judgments from Crimean courts on criminal draft evasion cases and identified 71 criminal draft evasion cases and 63 guilty verdicts between 2017 and 2019. The true number of such cases is most likely higher, as not all cases and judgments have been made public. In most cases, defendants were fined between 5,000 and 60,000 rubles (US$77 to $1,000).

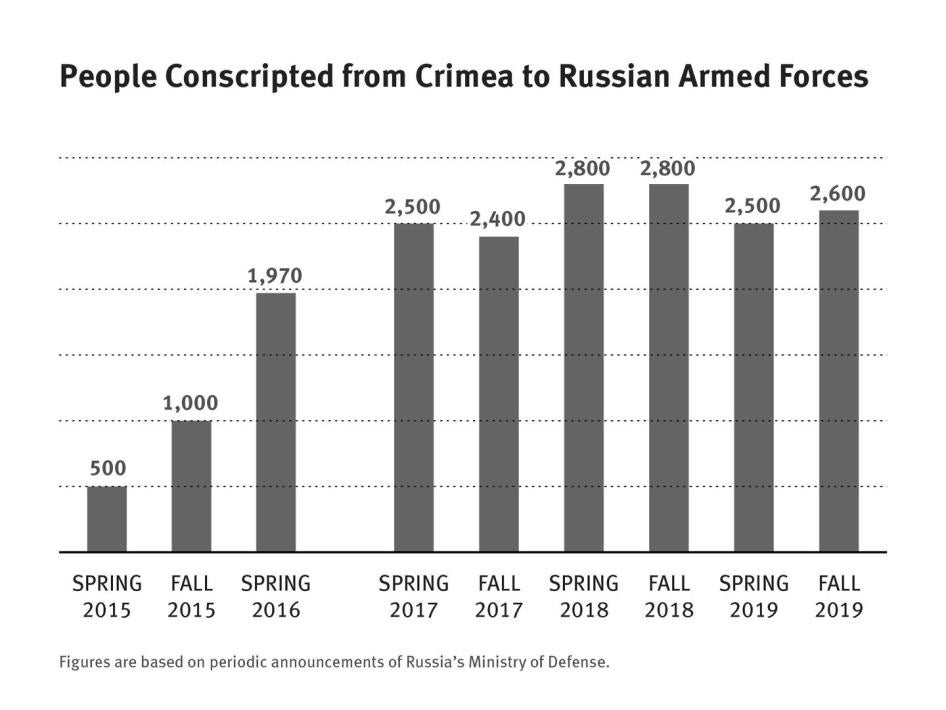

Since Russia occupied Crimea, the authorities have conscripted about 18,000 to 18,900 men there, according to estimates based on data provided by Russia’s Defense Ministry. At least 3,300 men from Crimea were enlisted through the draft in spring 2019, a significant increase compared with the 500 men enlisted in the first conscription campaign there in 2015. For the fall 2019 campaign, Russian authorities plan to enlist a total of 132,000 men, including about 2,600 from Crimea.

Under Russian law, draft evasion is a criminal offense punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison.

Legislative amendments to the Law On Military Obligation and Military Service, which entered into force in September 2019, introduced new requirements for men eligible for conscription to register for military service not only at their residential address, but also at their place of work or study. Men who fail to register will risk encountering difficulties getting jobs. For Crimean residents, as for Russian citizens, the choice is between being conscripted or facing a real risk of a criminal prosecution.

Since 2016, Russian authorities have been sending conscripts from Crimea to serve at military bases located in the Russian Federation. For example, about 85 percent of the men conscripted in spring 2019 were sent to Russian Federation bases.

Russian authorities have also been carrying out a widespread advertising campaign for enlistment in Sevastopol, Simferopol, and other cities in Crimea, as well as providing military propaganda for schoolchildren in Crimea.

Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, to which Russia is a party, an occupying power may not compel residents of the occupied territory to serve in its armed or auxiliary forces. It also explicitly prohibits any “pressure or propaganda which aims at securing voluntary enlistment.” These prohibitions are absolute, and their violation is a grave breach of the conventions.

The United Nations (UN) Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine has repeatedly condemned the unlawful conscription by Russian authorities in Crimea. The mission stated that forced enlistment also “adversely affects the enjoyment of human rights of potential conscripts, restricting their free movement and access to education and employment.”

The Ukrainian government has repeatedly protested Russia’s conscription in Crimea.

In resolutions adopted in 2014 and 2016, the UN General Assembly affirmed its commitment to the “sovereignty, political independence, unity, and territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders” and called on Russia to uphold its obligations under international law as an occupying power.

The Prosecutor’s Office of Crimea, a Ukrainian government agency based in Kyiv, told Human Rights Watch that it regularly gathers data on forced enlistment in Crimea. It includes this information in its reports to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Although Ukraine is not a member of the ICC, it has accepted the court’s jurisdiction over alleged crimes committed on its territory since November 2013. The ICC prosecutor’s preliminary examination is ongoing as to whether an investigation into abuses committed during the armed conflict is merited.

Russia has occupied Crimea since 2014 and continues to perpetrate human rights violations against people there for expressing pro-Ukrainian views. “Russia should stop conscripting people in Crimea and fully abide by its obligations under the Geneva Conventions,” Williamson said. “It can’t simply will away international law.”

For additional details on the Human Rights Watch findings about Russian conscription in Ukraine, please see below.

Human Rights Watch recalls that as a matter of international law, Russia has been an occupying power in Crimea since at least late February 2014 and assesses its actions with respect to the law on occupation under international humanitarian law.

To examine criminal prosecution cases for draft evasion in Crimea, Human Rights Watch consulted several online Russian government court registries that include rulings from courts in Crimea. Human Rights Watch also reviewed judgments available on websites of individual courts in Crimea. That data is not exhaustive as not all court proceedings and decisions are posted online. Human Rights Watch also spoke with experts from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as the Crimean Human Rights Group, that monitor conscription and other human rights abuses in Crimea, and met in Kyiv with representatives of the Prosecutor’s Office of Crimea.

Conscription in Russia and Crimea

Russia carries out conscription campaigns twice a year, in the spring and in the fall. Since Russia began its occupation of Crimea in 2014, it has carried out nine conscription campaigns. October 1, 2019 was the beginning of the 10th campaign, which will continue until December 31.

Compulsory conscription applies to men deemed eligible for military service between ages 18 to 27, who have taken Russian citizenship and who have not performed military service in another country’s army.

Penalties for Draft Evasion in Crimea

Under Russian law, draft evasion is penalized under arts. 21.5, 21.6, and 21.7 of the Code of Administrative Offenses and art. 328 of the criminal code. As a criminal offense, draft evasion is punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison. People who have served out penalties for draft evasion remain obligated to serve in the armed forces.

Human Rights Watch analyzed court data for Crimea for 2017, 2018, and 2019 and identified 71 criminal draft evasion cases and 63 guilty verdicts: 20 as of October 15 in 2019, 35 in 2018, and 8 in 2017. The true number of such cases is likely to be higher, as not all cases and not all judgments have been made public. In the cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch, criminal penalties ranged from a fine of 5,000 to 60,000 rubles (between approximately US$77 and $1,000). One verdict by the Pervomaisky District Court of Crimea on May 17, 2018 was an eight-month conditional (suspended) sentence for a defendant who pleaded guilty.

Most judgments reviewed state that the accused were acting with “criminal intent of evading military service” by either failing to appear for military medical certification or failing to appear at the military base to begin service. In most judgments, courts requested that the accused’s personal military conscription files be returned to the local draft commission office, apparently for future enlistment.

For example, on September 12, 2019 the Sudak City Court in Crimea considered the case of a sales manager charged with criminal draft evasion for repeated failure to appear for medical certification after being officially summoned. The accused pleaded guilty and was fined 20,000 rubles (US$308).

In another example, the Simferopol district court ruled on March 15, 2019 in the draft evasion case of a welder residing in Simferopol region. He was declared fit for service “with minor limitations” after a medical examination but failed to appear at the local draft board office after receiving a summons.

Taking into account that the accused pleaded guilty and also the fact that he was caring for his older parents who have disabilities, the judge closed the criminal case against him but ordered him to pay a fine of 50,000 rubles (US$770). The judge also ordered the court to send his personal conscription file to the local military commission, likely so that he can be enlisted in the immediate future.

In September 2017, a court in Evpatoria convicted a manager at a local company for draft evasion and fined him 20,000 rubles (US$313) for failing to appear at the military draft commission office after receiving an official summons. At the court hearing, the man stated that he was not able to report for duty because he was recovering from genital surgery. The surgery allegedly took place after he passed the medical examination that found him eligible for service but before he was summoned.

The court ruled against him, stating that he was eligible for service because he did not present any complaints during his medical examination, because the examination and treatment he underwent later were conducted in a private clinic, rather than a state hospital, and because he did not present the commission with any medical documentation about the surgery.

Referring to the man’s failure to appear, the court claimed that he “was fully aware of the public danger his criminal actions posed, foresaw that [his actions] could inevitably trigger the socially dangerous consequences in the form of evading military service and wished [for this outcome].”

The Crimean Human Rights Group told Human Rights Watch that as of October 8, 2019 it had documented 76 guilty verdicts since 2015, and was aware of two more cases still under consideration by Crimean courts and one under investigation. The group’s expert, Olexander Sedov, confirmed that the real number of cases and guilty verdicts is likely to be higher because many verdicts are not published. Sedov also said that the number of criminal verdicts for draft evasion in Crimea has been growing steadily since 2015, with 20 to 30 more verdicts resulting from each conscription campaign.

The UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine identified 29 guilty verdicts against Crimean residents for draft evasion between 2017 and 2019.

Russian law envisages alternative civic service for people who conscientiously object to military service. However, in practice, being allowed to perform alternative civic service can be difficult to access in Russia. Sergey Krivenko, a board member of the Memorial Human Rights Center and the head of a human rights group, Citizen and the Army, told Human Rights Watch:

In Russia, the law and its implementation are two very different things. Legally, one is not required to prove anything, just announce your beliefs and explain to the conscription commission why those beliefs contradict serving in the army. Any beliefs: pacifistic, political, religious. Unfortunately, in practice, the commission members very often turn the meeting into a court hearing, start shaming the guy, or accuse him of not loving his motherland enough, etc.

Because Russia is violating its obligations as an occupying power by conscripting men in Crimea, residents of the peninsula who do not want to serve with the Russian armed forces should not have to apply for alternative civic service or to perform any alternate service.

In practice, Russia insists that residents of Crimea who oppose military service apply for alternative service, and according to another expert from the Crimean Human Rights Group, in some cases those who cited their religious beliefs as the reason for applying for alternative service were required to provide documents from their religious organizations proving that their beliefs contradict military service.

Crimea residents also face other difficulties with alternative service. For example, in October 2018, the Nizgnegorsky District Court in Crimea found a Crimean Tatar man guilty of evading alternative service and sentenced him to 240 hours of community service. The man appealed the decision, alleging that he left his place of alternative service because of the extremely poor living conditions he was placed in. Russian law tasks local authorities with providing people performing alternative service with living accommodations and ensuring that their everyday needs are met. In November 2018, the appellate court upheld his conviction.

Imposition of Russian Citizenship in Crimea

Russian authorities are conscripting people in Crimea who have taken Russian citizenship. Following the occupation, the Russian government moved swiftly to bestow Russian citizenship and passports on residents of Crimea. In line with its March 2014 law, On the Acceptance of the Republic of Crimea into the Russian Federation and the Creation of New Federal Subjects – the Republic of Crimea and the City of Federal Significance Sevastopol, Russia required any permanent resident of Crimea who held Ukrainian citizenship to undergo a process of declaring intent to maintain Ukrainian citizenship.

Russia has not simply offered Russian citizenship to residents of Crimea, but rather has compelled residents to choose between Ukrainian and Russian citizenship while imposing adverse consequences, directly and indirectly, on those who choose to retain Ukrainian citizenship. In addition, there were serious flaws in the process for Ukrainian citizens who sought to retain Ukrainian citizenship. Some Ukrainian citizens were unable to exercise their choice to retain citizenship and had Russian citizenship imposed on them. Others were subject to harassment and intimidation for not obtaining Russian citizenship. In such circumstances, the imposition of Russian citizenship in Crimea was coercive.

More than five years later, the majority of Crimean residents have obtained Russian passports. While many may have genuinely wanted them, many people ended up accepting Russian citizenship out of necessity, because otherwise they could not get health care, or had difficulties seeking a job.

Ukrainian citizens have not been guaranteed the same rights as Russian citizens. For example, only Russian passport holders are allowed to occupy government and municipal jobs. Getting health insurance is contingent upon having a Russian passport or a permanent residence permit. Crimean residents who chose not to renounce their Ukrainian citizenship suffer discrimination and are considered foreign migrants with no guaranteed right to remain in Crimea.