(Nairobi) – Violence threatening civilians has surged in recent months in the Central African Republic’s south-central and southeastern regions. To protect people at risk, the United Nations Security Council should renew the mandate of the UN peacekeeping mission before it ends on November 15, 2017, and approve an October 18 request by Secretary-General António Guterres for 900 more troops.

United Nations peacekeepers have been instrumental in protecting civilians in many instances; the 15-member Council should give the peacekeeping mission, MINUSCA, the additional resources the UN says it needs to protect civilians from attacks, including sexual abuse.

“The rate of civilian killings in the Central African Republic in 2017 has been alarming, and in many areas across the country civilians are desperate for protection,” said Lewis Mudge, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Security Council should give the mission the resources it needs to protect civilians, including sufficient troop numbers to respond to the resurgence of violence threatening civilians and to protect camps for displaced people.”

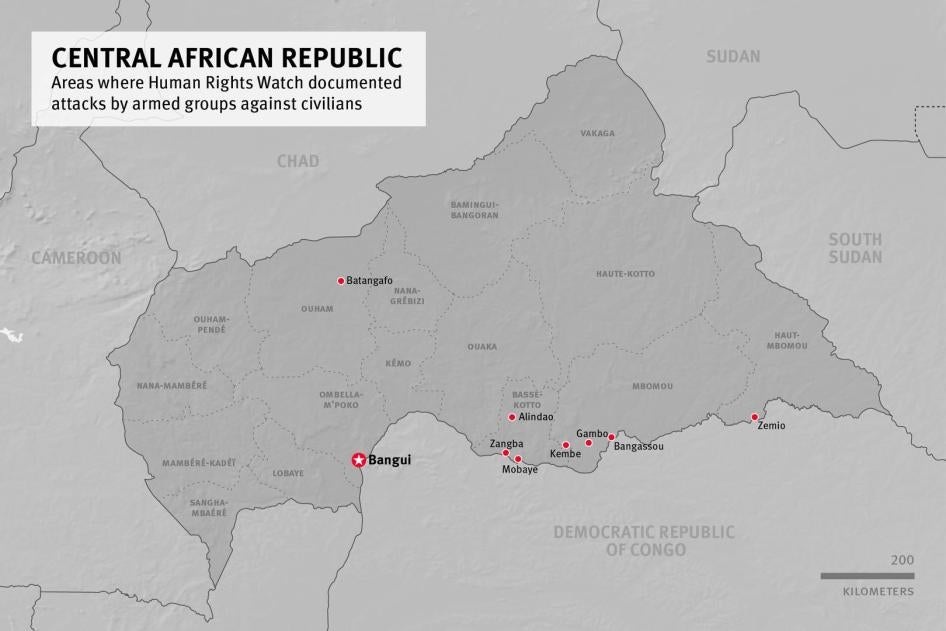

In August, September, and October, Human Rights Watch documented the killings by armed groups of at least 249 civilians since May, most in the south-central and southeastern parts of the country. The figure does not represent the total number of civilians killed nationwide, nor the many killings in remote and difficult to access areas.

Human Rights Watch also documented 25 cases of rape by armed groups in Basse-Kotto province in the same period, part of a pattern of systematic rape and sexual abuse of women and girls by armed groups over the past five years.

Human Rights Watch found in the cases it documented that if UN peacekeepers had a presence or could be deployed quickly, they were able to help stop attacks on civilians, or limit violence and save lives. In other cases, the absence of troops in the area left civilians unprotected. Ten peacekeepers have lost their lives during 2017 in attacks by armed groups in the country.

The current fighting has forced tens of thousands of people to flee their homes since May, bringing the total number of internally displaced people in the country, based on UN figures, to 600,300, and the total number of refugees to 518,200, the highest since mid-2014.

Most of the abuses Human Rights Watch documented were by factions of the Seleka rebels, including the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC) and the Central African Patriotic Movement (MPC), and by anti-balaka forces. Some killings were carried out by armed men who were not apparently part of either group.

In Basse-Kotto province Human Rights Watch documented the killing of 188 civilians between May and August, as result of attacks on civilians during hostilities between UPC and anti-balaka forces, as well as the 25 rapes. UN peacekeepers had no presence in the area when the attacks began, but arrived in the town of Alindao days after the hostilities began and were able to halt the attacks on civilians.

“They hit me and threw me on the ground,” said “Francine,” 34, of the UPC fighters. “Then they started to rape me. My [5-year-old] child was watching and wanted to help me. But they shot him in the side, and he died.”

On July 29, fighters from the MPC Seleka faction attacked a displacement camp in Batangafo and surrounding neighborhoods, killing at least 15 people, including three with disabilities, and burning approximately 230 homes and makeshift huts in the camp. One of the victims with disabilities, Gerard Namsoa, 56, could not flee when his home was set on fire. “He tried to crawl out, but he could not escape in time,” one of his relatives said.

On May 13, anti-balaka forces attacked the Muslim neighborhood of Tokoyo in Bangassou, Mboumou province. Nine survivors who fled to Bangui estimated that fighters killed at least 12 civilians, including the town’s imam, Mahamat Saleh, as they tried to seek safety in the mosque. Peacekeepers transported Muslims from the mosque to the Catholic Church, where they continue to provide protection. Approximately 1,500 Muslim civilians are there, according to UN sources and the residents who recently fled.

Civilians in the eastern region of the country had been spared from many targeted attacks in recent years, but they are now more vulnerable after the withdrawal of Ugandan army troops and United States military advisors in early 2017. Those forces had been deployed to the region for operations against the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a Ugandan-led armed group.

In Zemio, a town previously protected by Ugandan troops, at least 28 civilians have been killed since late June, including during an attack by a local armed group on the town on June 28 and another attack by the same group on a displacement camp in the town on August 17. Both attacks, carried out by local armed Muslims without a clear link to the Seleka, are thought to have been pre-emptive efforts due to the growing presence of anti-balaka in the area. A MINUSCA contingent has been stationed in the town since 2015, but it was unable to protect civilians during these attacks. Since the attacks, most town residents have fled to neighboring Congo.

MINUSCA first deployed to the Central African Republic in September 2014 and currently has 12,342 armed members. Under Chapter VII of the UN Charter it is authorized to take all necessary means to protect the civilian population from threat of physical violence and to “implement a mission-wide civilian protection strategy.”

In areas most prone to violence, the UN should expand its patrols and, consistent with the mission’s mandate, use appropriate force to protect civilians under imminent threat, Human Rights Watch said. The Security Council should ensure the mission has all the resources it needs so it can protect civilians, including the 900 additional troops requested by the Secretary-General.

To address entrenched impunity for war crimes, the national government, the UN, and donors to the Central African Republic should increase their support for the Special Criminal Court (SCC) – a new judicial body with national and international judges and prosecutors that has a mandate to investigate and prosecute grave human rights violations in the country since 2003. The new court offers a chance to hold accountable commanders on all sides of the conflict who are responsible for war crimes, Human Rights Watch said.

The UN mission should continue its technical and logistical support to the SCC to ensure that it can quickly become operational and carry out effective investigations and prosecutions. National and international bodies should also ensure ongoing support to strengthen the national judicial system.

“Ensuring that those responsible for abuses are brought to justice – regardless of rank or position – is critical to ending the cycles of violence and abuse in the Central African Republic,” Mudge said. “The government in Bangui, the UN, and the country’s donors should do what it takes to get the Special Criminal Court the resources, personnel, and technical support it needs.”

Background

The Central African Republic’s current crisis began in late 2012, when mainly Muslim Seleka rebels ousted President Francois Bozizé and seized power through a campaign of violence and terror. In response, anti-balaka groups were formed and began carrying out reprisal attacks on Muslim civilians in mid-2013. African Union and French forces pushed the Seleka rebels out of the capital, Bangui, in 2014.

After two years of an interim government, relatively peaceful elections were organized and Faustin-Archange Touadéra was sworn in as president in March 2016. Since then, violence and attacks against civilians have continued, with Seleka factions and anti-balaka groups still controlling large swathes of the country, especially in the eastern and central regions.

Numerous armed groups, including the UPC and MPC Seleka factions, signed a ceasefire agreement on June 19. Another ceasefire was signed on October 9, again between several armed groups, including the UPC, the MPC, and some anti-balaka groups.

Human Rights Watch documented recent killings in and around Alindao, Mobaye, and Zangba, Basse-Kotto province; in Batanagafo, Ouham province; in Bangassou, Mboumou province; and in Zemio, Haut-Mboumou province. In some cases, displacement camps and aid workers came under attack.

The Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC)

The UPC is controlled by Ali Darassa Mahamant, a former commander in the Chadian rebel group the Popular Front for Redress (Front populaire pour le redressement, FPR). Darassa joined the Seleka and officially created the UPC in September 2014. Until early 2017 he was based in Bambari, in Ouaka province. In February, MINUSCA asked Darassa to leave Bambari. He now has a base in Alindao.

The UPC has close links to ethnic Peuhl, and armed Peuhl often fought with the UPC during attacks.

The Central African Patriotic Movement (MPC)

Mahamat Al Khatim is the military commander of the Central African Patriotic Movement (MPC), which controls territory across the center-north of the country. The group is often allied with another Seleka offshoot, The Popular Front for the Renaissance in the Central African Republic (Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique, FPRC). FPRC and MPC fighters have killed civilians in past attacks, such as when they razed a camp for displaced people in Kaga-Bandoro in October 2016, killing at least 37 civilians and wounding 57.

The groups have also fought the UPC over the past year and, at times, have allied themselves with anti-balaka fighters.

Alindao, Basse-Kotto Province

On May 9, 2017, UPC fighters and local Muslims attacked Alindao, focusing on the Paris-Congo and Banguiville neighborhoods. Residents told Human Rights Watch that they had seen anti-balaka in these areas, which most likely prompted the attacks. Survivors and witnesses said that the attackers searched door-to-door, looking for men to kill and, in some instances, women or girls to rape.

One survivor from Paris-Congo saw Seleka kill a member of her family, 65-year-old Edouard Ngakoto, after the fighters entered the neighborhood:

Edouard told us all to get under the bed. We heard the Seleka break our door down with axes and machetes. The attackers came inside and yelled for all the men to leave the house. Edouard left so they would not find me too. I watched as the Seleka pulled him outside and I heard him scream as they hit him with machetes…Then they chased me and some of my children out of the house and started to burn it… As we were running I saw his body. He had been hit in the head with a machete and they cut open his stomach with a knife.

On May 9, in Alindao, UPC fighters attacked a group of civilians, fatally shooting Bruno Bagaza, 48, a Red Cross volunteer who was wearing his uniform. They then hacked Bagaza’s 16-year-old nephew, Grace-à-Dieu , to death by machete. “The Seleka did not listen to the men as they pleaded for their lives,” a witness said. “They killed them and threw their bodies in the well.”

A relative of Bruno Bagaza said:

It was tense. Bruno put on his Red Cross emblem and we stayed at the house. The shooting got closer and soon people came and broke down the door. There were seven Peuhl Seleka, armed with Kalashnikovs and machetes. They yelled at Bruno, “You are an anti-balaka commander!” Bruno said that he was not, but one of them just shot him in the chest. They pulled his body outside and threw it down a well in the yard… The Peuhl then went back into the house and saw Grace-à-Dieu. They pulled him outside the house and killed him with machetes. He was yelling, “Forgive me! Forgive me! I do not even know what I have done!” One of the Seleka hitting him said, “Today we are going to finish all of you.” When he was dead they threw his body down the well.'

That same day, Seleka fighters shot and killed 75-year-old Dieudonne Kpambagnin in his home in the Paris-Congo neighborhood. His son said:

They were all in uniform and they had Kalashnikovs. They told my father to give him money, but he said he had none. They then told us to go into the house. They asked again for money and my father said, “I don’t have any, if you must, just shoot me.” A fighter saw a strongbox that has some coins for the church and he shook it. He said, “You said there was no money…what is this?” My father tried to explain it was for the church but one of the Seleka told him to get on his knees. Once he was on his knees he shot him in the head.

The UPC and Muslim civilians burned hundreds of homes in Banguiville and Paris-Congo. As of October 5, approximately 18,000 people were living in a displacement camp at the town’s Catholic parish.

Sexual Violence in Basse-Kotto

Survivors of sexual violence interviewed by Human Rights Watch said fighters assaulted them in their homes, during door-to-door raids, or as they fled the violence. Survivors said Seleka UPC fighters raped at least 30 other women and one man who were with them in their homes or as they fled. In several cases, the rapes were exacerbated by additional violence, including torture or killing of family members. Fighters raped some survivors in front of their children or other relatives.

“Irène,” 36, said she was outside her house in Alindao’s Banguiville neighborhood on May 9 when Seleka UPC forces appeared, pointed their guns at her, and demanded that her husband leave the house. He tried to flee but fighters shot him in the legs. When the couple’s 5-year-old daughter began crying the Seleka tied her to a post outside the house. Irène said that two of the fighters raped her, and she was made watch as their commander raped her husband, then killed him and their daughter:

When one took me by force, my husband said, “No, that’s a poor woman. Don’t do anything to her.” One came and told him to be quiet and that he should undress... Their commander said, “Me, I’m going to sleep with her husband.” When I lowered my head, he told me to lift my head and watch. When I cried out, “There’s no reason to hurt us both,” one of them said, “Shut up.” Then they put cloth over my mouth. Two came and took my two legs. They held them open. When the first one finished raping me, he called another one to bring a piece of clothing. He took [the clothing) and put it inside my vagina to clean out where the first man had been. I didn’t know what to do but scream. It hurt too much.

My daughter was crying. One said, “Why is the child crying like that?” I heard them shoot the child… I heard them fire and then it was silent. I didn’t hear her anymore.

They shot my husband in the head with two bullets… Before they raped me, I saw them start to torture him. They took a piece of wood and hit him with it. They took a military knife and cut his arms. They wrote their names on his arms. I started to cry and cry.

“Mélanie,” 31, also said that Seleka UPC fighters raped her and killed her husband in Banguiville on May 9. Seleka fighters stormed their house, forced Mélanie’s husband to undress, bound him with rope, and took him away, she said. Seleka fighters then attacked her:

Two of them stopped me. They raped me. The other women who were with me, others [fighters] started to rape them. There were six others – they were also all raped… When [the fighters] finished, they told me to leave quickly. I fled to go to the fields. I was really suffering… I had wounds on my vagina – I couldn’t walk.

Mélanie found her husband’s corpse the next day with his throat cut and bullets in his stomach.

Mélanie said she did not get immediate health care because the hospital in town had been ransacked and was not functioning. When she did get care in Bangui, she tested HIV-positive, which she attributes to the rape, though Human Rights Watch cannot confirm her HIV status prior to the assault.

Most of the survivors of sexual violence interviewed said they did not get essential post-rape medical or mental health care until they reached Bangui, days or weeks later, and some had not received any post-rape care. Delays in access to care were often due to services not functioning, lack of knowledge about services, or lack of funds to pay for medical care and associated costs.

Alindao Displacement Camp

At least 32 people have been killed in and around Alindao since the May 9 fighting, many after they left the displacement camp in the town to look for firewood or food.

“Gervais,” 32, said two UPC fighters on a motorcycle stopped him and two friends on August 21 on the road to nearby Mingala while they were looking for food. The fighters accused the men of being thieves and took their money and phones. One of the fighters then took the two other men, Rodrigue Balipou, 36, and Oban Bakoumbou, 30, on foot to the nearest UPC base, while “Gervais” waited as the other fighter fixed the motorcycle. “I saw my two friends leave and then I heard shots,” Gervais said. “I was scared. They already took our money, so I knew the only reason they kept us was to kill us. I decided to run. As I did the Seleka fighter shot at me, but I was able to hide.” Gervais said he has not seen Balipou or Bakoumbou since and presumes they are dead.

The UPC’s political coordinator, Hassan Bouba, denied that UPC members carried out any abuses on or since May 9 and blamed anti-balaka forces for violence and attacks on civilians. Anti-balaka fighters had attacked the UPC and civilians in the Paris-Congo and Banguiville neighborhoods in the weeks before May 9, he said, but Human Rights Watch heard no reports of those incidents in Alindao. “We never attacked Paris-Congo or Banguiville,” Bouba told Human Rights Watch on September 8. “The anti-balaka have forced people from their homes and said they would kill them if they don’t go to the camp at the Catholic church. The anti-balaka burned the homes in Alindao.”

On October 10, President Touadera named Bouba a presidential adviser.

A MINUSCA contingent in Alindao has assisted people in retrieving their killed relatives’ bodies. However, the lack of security means people fear leaving the camp, rebuilding destroyed structures, or moving back to their neighborhoods.

Bangassou

On May 13, at about 5 a.m., anti-balaka fighters in Bangassou attacked the town’s Muslim neighborhood, Tokoyo. Nine residents interviewed in Bangui said they had heard rumors of an attack for several weeks.

“When the shooting started I took my kids and we ran to the mosque,” said one survivor, “Rachida,” 35. “I saw anti-balaka shooting at us. They had both homemade guns and Kalashnikovs.” The imam, Mahamat Saleh, was shot dead while fleeing, along with at least 11 other civilians, Rachida and several others said.

An estimated 2,000 people spent three days at the town’s Central Mosque, surrounded by the anti-balaka and protected sporadically by MINUSCA forces, the residents said. Some Muslim men fought back with their own guns but the anti-balaka continued shooting at the mosque compound. People who sought shelter at the mosque said that the MINUSCA presence in the town and their use of force against the anti-balaka prevented a massacre.

On May 16, MINUSCA troops escorted the people from the mosque to the town’s catholic parish, where about 1,500 people continue to receive protection.

Around June 7, the anti-balaka destroyed the Central Mosque, residents said.

Zemio

Zemio had been spared violence until this year, when Ugandan forces under the Regional Cooperation Initiative for the elimination of the LRA (RCI-LRA), an African Union (AU) mission, ended their mission and left the country. While the AU recently renewed its mandate, the military component of the RCI-LRA is over. MINUSCA maintains a small contingent in Zemio after the departure of the Ugandan forces.

As word spread of the mosque attack in Bangassou on May 13, tensions began to rise between the Muslim and the non-Muslim parts of town, multiple residents said. These tensions culminated in an attack on the non-Muslim neighborhoods by armed Muslim men on June 28 that left 12 civilians dead.

One Zemio resident said:

I was at work in the market that morning. I heard the shooting. I saw people running and then I saw people from the Muslim neighborhoods attacking. I closed my shop and ran home to get my family. I could see the attackers – they were dressed in a variety of clothing: some were in military clothes, others in civilian clothes. They were attacking people and pillaging and burning homes. They were shooting at any man they saw. I just kept running. I took my family into the surrounding woods to hide. That evening I went back into town. Our house and shop had been destroyed. I saw bodies in the street.

Another resident said he fled into the surrounding woods when the attack began, but returned to town later that day:

At around noon I went back into the town with some other men to see the damage. The attackers had moved from neighborhood to neighborhood. I saw the body parts of a man I know, Mbolix – he had been cut into pieces by a machete. We collected the parts and put them in a bag to bury it. I went to my grandmother’s house and she had been burned to death inside it. She was around 72-years-old. I was traumatized.

After the attack, much of the town’s population set up a displacement camp around the hospital. Tensions increased further as anti-balaka groups in the town began to fight with Muslims. On July 11, armed men entered the hospital and threatened Muslim patients, residents said. They shot at the patients and struck a baby in the head, killing her instantly, said non-governmental organizations and residents.

On August 17, armed Muslims attacked the displacement camp, killing at least seven civilians. “When the shots got close, it was chaos,” said one camp resident, “Thierry.” “People ran any way they could to get into the bush. I had to jump over bodies as I fled.” Another resident, “Alphonse,” said he was outside the camp when the attack started and ran back to look for his family. “The shooting was too much, so I hid,” he said. “I saw the anti-balaka in the camp, trying to tell the population to hide. Then the Muslims came and started shooting at the anti-balaka. But they did not care about who they aimed at, they just shot at any man they could see.”

Batangafo

Batangafo, in Ouham province, has also had a spike in attacks on civilians. On July 29, MPC fighters attacked the neighborhoods around the displacement camp in town, and then attacked the camp itself, burning more than 220 huts. The violence, which started as tit-for-tat fighting between the anti-balaka and MPC over stolen motorcycles, left at least 15 civilians dead.

One witness, a niece of 62-year-old Robert Kangabe, the chief of Zibobaga neighbourhood, said that her uncle had a physical disability and could not easily walk:

When the attackers came toward us, everyone ran. My uncle had to walk with a cane and could not run. I stayed with him because we thought the Seleka would not kill him, because he is old and cannot really move. The Seleka broke down the door, entered our house and searched for money. As they did, one of the fighters pulled my uncle up and walked him outside. My uncle said, “I am not anti-balaka, I can’t be, I am the chief of the quartier.” But they told him to walk away. He started to walk slowly and they shot him twice in the back.

Another resident of Batangafo, “Pierre,” ran to the displacement camp when the attack began. His brother, 57-year-old Jacob Goumalao, refused to run as he wanted to stay and protect his belongings. “I watched the Seleka approach Jacob’s house from about 200 meters away,” “Pierre” said. “They were Seleka from town, they were dressed in uniforms. I could see them asking Jacob for money, but he said he did not have any. So they shot him twice in the chest and searched him.”

“Edith,” 47, said she hid in a family compound in the Tarabanda neighborhood on the outskirts of the camp. When the Seleka began the attack on the displacement camp, about 50 people fled to the family compound, she said. They were hiding in a few buildings, mostly women and children, when the Seleka entered the compound and announced they were looking for men. A relative of Edith’s, 51-year-old Victor Ouingaïfonan, was hiding in one of the homes.

“They pulled Victor from where he was hiding and took him outside,” Edith said. “One Seleka shot him in the chest. He was still breathing so another Seleka walked up and cut his throat. He did not even have time to beg for his life, they just shot him right away.” The Seleka then pulled Dieudonne Wabone, a 60-year-old blind man, outside. “They then found Dieudonne hiding among the women,” Edith said. “As he was pulled outside, he said, ‘My sons, look at me. I am old and blind. I was just on the way to the camp to look for food. Why kill me?’ The Seleka did not respond, they just shot him in the chest.”

“Emmanuel,” who said he survived a Seleka attack on July 29, said:

I was running from the camp to the hospital when I came across a group of Seleka. They were pillaging homes. There were six of them. When they saw me, they surrounded me and told me to empty my pockets. I gave them my phone and a little money I had on me. I tried to explain that I was not anti-balaka but they did not even try to understand. One then struck me in the head with a machete. I fell on my stomach and he struck me on my back. They started to stab my arms and kick me until I passed out. At some point they left, they must have thought I was dead.

The head of the MPC in Batangafo, Abdullahi Mamat, said that he had arrived in Batanganfo around August 23 and knew nothing of the attack. However, he said he was sent there after the previous commander, Yaya Moussa, “made mistakes.”

Sources told Human Rights Watch that the MINUSCA contingent, using force, protected civilians in the area on July 29 after several hours.

On September 1, a Human Rights Watch researcher noted the presence of armed anti-balaka in the Batangafo displacement camp. Residents of the camp said the anti-balaka routinely arbitrarily detain people and demand payment for their release.

Gambo

On August 5, forces apparently from the UPC and Muslim civilians attacked and killed six volunteers working with the Red Cross in Gambo, Mboumou province. MINUSCA was not present in Gambo, but sent some troops to the area just after the killings.

Kembe

On October 10, at least 20 Muslims were killed by self-defense groups – Christian and animist groups who are often aligned with anti-balaka – in Kembe, in Basse-Kotto. MINUSCA troops were sent to Kembe just after the attack.