This memorandum addresses key human rights concerns in Lebanon relevant to the Lebanon-EU Partnership Priorities and the EU-Lebanon Compact.

These issues include lengthy pre-trial detention, ill-treatment and torture, freedom of expression, the use of military courts, violence against Syrian refugees, women’s rights, sexual orientation and gender identity, residency requirements for refugees, barriers to education for refugee children and children with disabilities, and abuses against migrant domestic workers.

Human Rights Watch welcomes the recognition in the Lebanon-EU Partnership Priorities that human rights are an essential element of EU-Lebanon relations and submits the following recommendations to assist the EU in supporting Lebanon’s compliance with its international human rights obligations.

The information below is drawn from our research in Lebanon, where we maintain an office and closely monitor the situation, including through first-hand interviews and documentary evidence.

1. Human Rights Issues Concerning Security and Counter-Terrorism as well as Governance and Rule of Law (Partnership Priorities 1 and 2)

a. Lengthy Pretrial Detention, Ill-Treatment, and Torture

Detainees in Lebanon suffer from lengthy pretrial detention and widespread ill-treatment and torture by security services. Lebanon’s parliament on October 19, 2016, established a National Human Rights Institute (NHRI), which will include a committee to investigate the use of torture and ill treatment, and a Committee for the Protection from Torture, which will have the authority to conduct regular unannounced visits to all places of detention, investigate the use of torture, and issue recommendations to improve the treatment of detainees. Although the law of October 19 adopts a broad definition of torture, Lebanon has yet to criminalize all forms of torture. The Lebanese judiciary rarely, if ever, prosecutes people alleged to have tortured detainees. While some judges set aside confessions extracted under torture, others continue to accept such confessions despite the prohibition in Lebanese law on using forced confessions to convict people of crimes.

The EU should press Lebanon to live up to its commitment to reduce pre-trial detention.[1] It should exert pressure to ensure that Lebanon’s commitment to improve prison management includes the introduction of effective safeguards against torture and ill-treatment and cooperation with the newly created national preventative mechanism.[2] EU capacity building projects within the Lebanese security sector should include accountability and oversight mechanisms to ensure an end to the use of torture.[3]

b. Freedom of Expression

Defaming or criticizing the Lebanese president or army is a criminal offense. On August 22, 2016, a woman was sentenced by a military court to a month in prison after alleging that military intelligence members raped and tortured her in detention in 2013.

Lebanese law also criminalizes libel and defamation of public officials, authorizing imprisonment of up to one year. The lawyer and human rights activist Nabil al-Halabi was arrested on May 30, 2016 over Facebook posts criticizing government officials.

Under the agreed cooperation to protect free speech, the EU should press Lebanon to remove the crime of criminal defamation and cease using defamation laws to silence peaceful political criticism.[4]

c. Use of Military Courts

Lebanon routinely uses military courts to try civilians, including children, in violation of international law. The military courts do not guarantee due process rights and have used confessions extracted under torture. Fourteen people who protested against Lebanon’s waste management crisis were arrested in 2015 and have been referred to military courts for rioting, violence against police, and destruction of property. If found guilty, they face up to three years in prison.

Under the agreed cooperation to strengthen the independence of the justice sector, the EU should press Lebanon to strip military courts of criminal jurisdiction over civilians and should send monitors to observe military tribunal proceedings in which the accused are civilians.[5]

d. Women’s Rights

A lack of coordination in the response to sex trafficking continues to endanger women and girls. Syrian women appear to be particularly at risk. In March 2016, police freed as many as 75 Syrian women from brothels. The country’s 2011 anti-trafficking law directed the Ministry of Social Affairs to establish a trust fund for victims, but it has not yet done so.

A 2014 law increased protection against domestic violence, but failed to criminalize all its forms, including marital rape. The law called for the establishment of police units specialized in family violence and of a fund to assist victims of domestic violence, but neither has been set up. Women continue to suffer discrimination under the 15 Lebanese personal status laws, which apply according to religious affiliation, including unequal access to divorce, residence of children after divorce, and property rights.

The EU should ensure that its support to Lebanon improves access to justice for victims of domestic violence and human trafficking. [6] It should press Lebanon to repeal all legal provisions which discriminate against women as well as to criminalize all forms of domestic violence, including marital rape. The EU should press Lebanon to set up family violence police units and the trust funds to assist victims of domestic violence and victims of trafficking, as mandated by Lebanese law.

e. Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Lebanese law criminalizes sexual relations outside marriage and “sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature.” Authorities have arrested persons allegedly involved in same-sex conduct and subjected some of them to torture including forced anal examinations. In February, a Syrian refugee was arrested by Lebanese Military Intelligence officers apparently on suspicion of being gay and then allegedly tortured while detained by the Military Intelligence, Ministry of Defense, Military Police, and Internal Security Forces.

The EU should ensure that its support for capacity building of criminal justice actors to ensure compliance with international human rights obligations includes respect for LGBT rights.[7] It should press Lebanon to ban the use of anal examinations as a method of torture.

2. Human Rights Issues Concerning Growth and Job Opportunities (Partnership Priority 3)

a. Restrictive Residency Requirements for Syrian Refugees

Since January 2015, Lebanon has required Syrian refugees age 15 and older to pay $200 per year and—if not registered with UNHCR—to obtain sponsorship by a Lebanese citizen to legally reside in Lebanon. Lebanon’s 2016 Country Response Plan on Syrian refugees estimated two-thirds of Syrian refugees have been unable to renew their legal status.

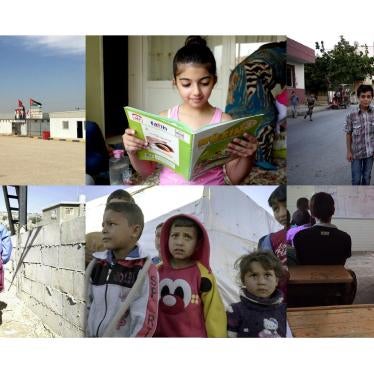

The residency requirements are one of the key factors that kept approximately 250,000 school-age Syrian children from accessing school during the 2015-2016 school year. Contrary to Lebanon’s refugee education policy, some school directors have required residency to enroll Syrian children. Those without residency are unable to search for informal work for fear of arrest, exacerbating poverty among refugees. Impoverished refugees often cannot pay for transportation to school or depend on child labor. Working children often drop out of school and are at risk of exploitation, arrest, violence, and hazardous work.

In the light of Lebanon’s commitment to seek ways to facilitate streamlining of residency regulations, including a waiver of residency fees, the EU should press Lebanon to abolish residency fees and sponsorship requirements and to ensure freedom of movement for Syrian refugees.[8] The EU should increase funding to support Syrians’ livelihoods, including income-generating work, and to help offset refugees’ school-related transportation costs. The EU should fulfill its commitment to enhance market access for Lebanese products, while ensuring that created jobs benefit both Syrian refugees and Lebanese citizens, along the same lines as the EU-Jordan Compact.[9]

b. Disincentives to Education and Causes of Dropouts of Syrian Refugee Children

Syrian refugee parents and children report problems in Lebanese public schools including widespread corporal punishment by public school teachers, a lack of language support for public school classes taught in English and French, inattentive teachers, and a lack of textbooks in some schools. As a result, students have dropped out.

As part of its commitment to support school quality, the EU should support the Lebanese Education Ministry in providing language support, and improved teacher training and the use of qualified Syrian teachers.[10] The EU should press Lebanon to live up to its commitment to improve child protection and referral mechanisms by enforcing the ban imposed in 2001 on corporal punishments in public schools and making sure that allegations of corporal punishment, harassment or discrimination are promptly investigated and redressed and teachers are held accountable.[11]

c. Access to Education for At-Risk Populations

Only about 5 percent of Syrian children aged 15-18 were enrolled in secondary schools in Lebanon during 2015. As public schools do not provide inclusive education, Syrian children with disabilities have very few options.

As part of its commitment to support access to education, the EU should support the Lebanese Education Ministry in ensuring that secondary-school-age children are included as a core part of the education response and that the back to school program providing free education for all children extends to grades 10-12.[12] It should also provide support to introduce inclusive education for all children in public schools, including children with disabilities.

d. Inadequate Framework for Non-Formal Education

Syrian children in Lebanon who are unable to access public schools often depend on non-formal education. In 2015, the Education Ministry withdrew support for programs operated by nongovernmental groups and shut down certain non-formal schools. The ministry has established a framework for non-formal education in 2016-17, but the role of nongovernmental groups remains unclear.

The EU should ensure that Lebanon fulfills its commitment to finalize the policy for non-formal education and urgently clarify the role of nongovernmental groups as partners in providing education.[13]

e. Insufficient Labor Law Protections for Migrant Domestic Workers

An estimated 250,000 migrant domestic workers are excluded from labor law protections. The kafala (sponsorship) system subjects them to restrictive immigration rules and places them at risk of exploitation and abuse. Migrant domestic workers seeking redress for abuse face legal obstacles and risk imprisonment and deportation.

In the light of the Lebanese commitment to promote the protection of marginalized population groups, the EU should press Lebanon to extend labor law protections to migrant domestic workers, abolish the kafala system, ensure that migrant workers have access to justice, and ratify the international Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.[14]

f. Waste Management and Right to Health

Lebanon has never had a national waste management policy, and since 1998 has relied on an emergency plan in Beirut and Mount Lebanon, while leaving outer municipalities to fend for themselves. As a result, there are 670 open dumps across the country, and the open burning of waste is common and has increased in urban areas following a 2015 waste management crisis. Testing by the American University of Beirut in one location found a 2,300 percent increase in carcinogens during burning days. Lebanese authorities have failed to address the burning or disseminate adequate information about the health risks for those exposed to open burning.

The EU should encourage Lebanon to fulfill its undertaking to build on good practices from successful waste management projects by adopting a national solid waste management strategy respecting the right to health of everyone in the country that covers the entire country and to adopt sustainable and environmental waste management approaches including decentralized recycling and composting.[15] Lebanon should adequately fund municipalities to manage their waste, conduct testing of the environmental consequences of its waste management policy, and publicize the results.

3. Human Rights Issues Concerning Migration and Mobility (Partnership Priority 4)

a. Forcible Returns to Syria and Denial of Entry to Asylum Seekers

Human Rights Watch has documented isolated forcible deportations of Syrians and Palestinians back to Syria, putting them at risk of arbitrary detention, torture, or other persecution. In January 2016, Lebanese authorities sent hundreds of Syrians traveling through the Beirut airport back to Syria without assessing their risk of harm upon return there.

In 2016, Lebanon continued to impose entry regulations for Syrians that effectively barred many asylum seekers from entering Lebanon.

The EU should make sure that its support to reinforce Lebanon’s integrated border management and to strengthen the capacity of Lebanese authorities to manage borders and prevent irregular migration within the framework of a planned mobility partnership, safeguards the right of asylum seekers to seek international protection when arriving at the border.[16] The EU should press Lebanon to allow asylum seekers to enter the country and to end and prevent forcible deportations to Syria.

[1] EU-Lebanon Partnership Priorities plus Compact, Annex to Decision No 1/2016 of 11 November 2016 of the EU-Lebanon Association Council agreeing on EU-Lebanon Partnership Priorities, UE-RL 3001/16 at 14.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid. at 5.

[5] Ibid. at 5, 14.

[6] Ibid. at 14.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid. at 12.

[9] Ibid. at 15.

[10] Ibid. at 17.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid. at 6.

[15] Ibid. at 18.

[16] Ibid. at 13,19.