(New York) – Two Tunisians formerly held in secret United States Central Intelligence Agency custody have described previously unreported methods of torture that shed new light on the earliest days of the CIA program, Human Rights Watch said today. The two men, Ridha al-Najjar, 51, and Lotfi al-Arabi El Gherissi, 52, independently recounted being severely beaten with batons, threatened with an electric chair, subjected to various forms of water torture, and being chained by their arms to the ceilings of their cells for long periods.

“These terrifying accounts of previously unreported CIA torture methods show how little the public still knows about the US torture program,” said Laura Pitter, senior US national security counsel at Human Rights Watch. “The release of these two men without the US providing any assistance or redress for their torture and suffering also shows how much the US still needs to do to put the CIA torture program behind it.”

Human Rights Watch last interviewed al-Najjar and El Gherissi in August 2016. They are among the 119 men the US admitted having held in secret CIA detention when the Senate Intelligence Committee, in December 2014, released a scathing 499-page summary (Senate Summary) of a 6,700-page, still-classified report about the CIA’s detention and interrogation program. The Senate Summary contains an inadequate description of the two men’s treatment while in CIA custody, Human Rights Watch said.

Al-Najjar’s and El Gherissi’s first-hand accounts shed light on CIA mistreatment during the earliest days of the CIA program, before Afghan Gul Rahman died in CIA custody on November 20, 2002. In response to Rahman’s death and other abuses, the CIA issued its first formal guidelines for detainee interrogations, though detainees continued to be brutalized.

US and Pakistani forces apprehended al-Najjar on May 22, 2002, in the southern port city of Karachi, and El Gherissi on September 24, 2002, in the northern town of Peshawar, near the border with Afghanistan. The Senate Summary says that the CIA identified al-Najjar as a bodyguard of Osama bin Laden. El Gherissi said his interrogators constantly accused him of being a member of Al-Qaeda or of having connections to terrorism. The US has not publicly provided information supporting these allegations, which al-Najjar and El Gherissi both deny and said they repeatedly denied to their interrogators.

The CIA then took custody of them and held them in several locations in Afghanistan. The one in which both said they suffered the most abuse is referred to as “Cobalt” in the Senate Summary but al-Najjar and El Gherissi called it the “Dark Prison” – as have other former prisoners held in the same facility. US authorities eventually transferred both to US military custody at Bagram airbase in Afghanistan.

Neither al-Najjar nor El Gherissi have previously publicly described their ordeal. US restrictions on communications at Bagram effectively prevented the two from communicating with the outside world while they were in military custody. The US transferred al-Najjar and El Gherissi to Afghan custody on December 9, 2014, and repatriated them to Tunisia six months later, on June 15, 2015. Tunisian authorities briefly detained the men, releasing both by the end of the month.

While the men were at Bagram, Tina Foster, executive director of the International Justice Network, sought to have a federal court review the lawfulness of their detention. But the courts denied her petition for habeas corpus, siding with the US Justice Department, which argued that Bagram was beyond the jurisdiction of US courts. Foster appealed to the US Supreme Court but the appeal was rejected as moot after the two men were released. Foster said that the entire time she represented the two detainees, the US government never permitted her to speak to them.

Human Rights Watch interviewed each man in separate locations using an Arabic language interpreter. Though the two spoke to each other at times while in US custody, they said they did not know each other prior to being apprehended, have not spoken in detail with each other about their mistreatment, and have not had contact since they were released from Tunisian custody.

Al-Najjar and El Gherissi described various methods of CIA torture, some never previously reported:

- Al-Najjar described forms of water torture, including waterboarding or water dousing while on a board, “Until I couldn’t breathe anymore.” El Gherissi said that his head was forced repeatedly into a bucket of water to get him to “talk.”

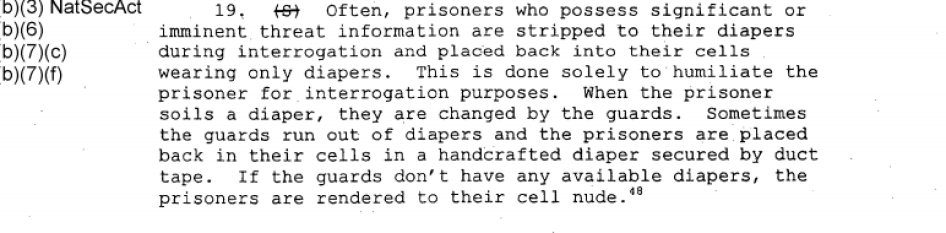

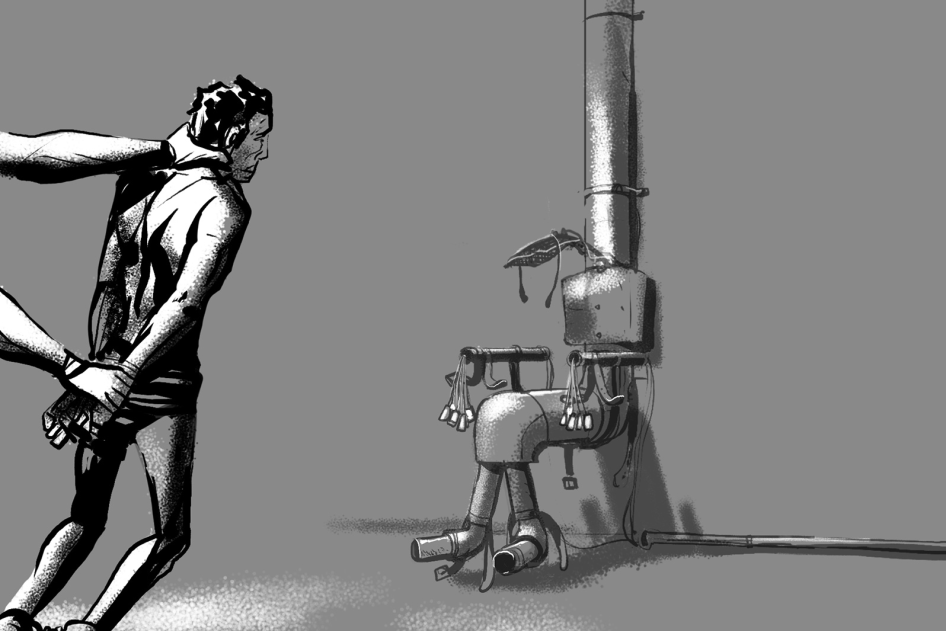

- Both men said that US interrogators showed them what they said was an electric chair – a metal chair with plugs attached to wires for the fingers and a wired cap – and threatened to use it on them. Their descriptions of the chair gave the impression it was make-shift, attached to a wall pipe.

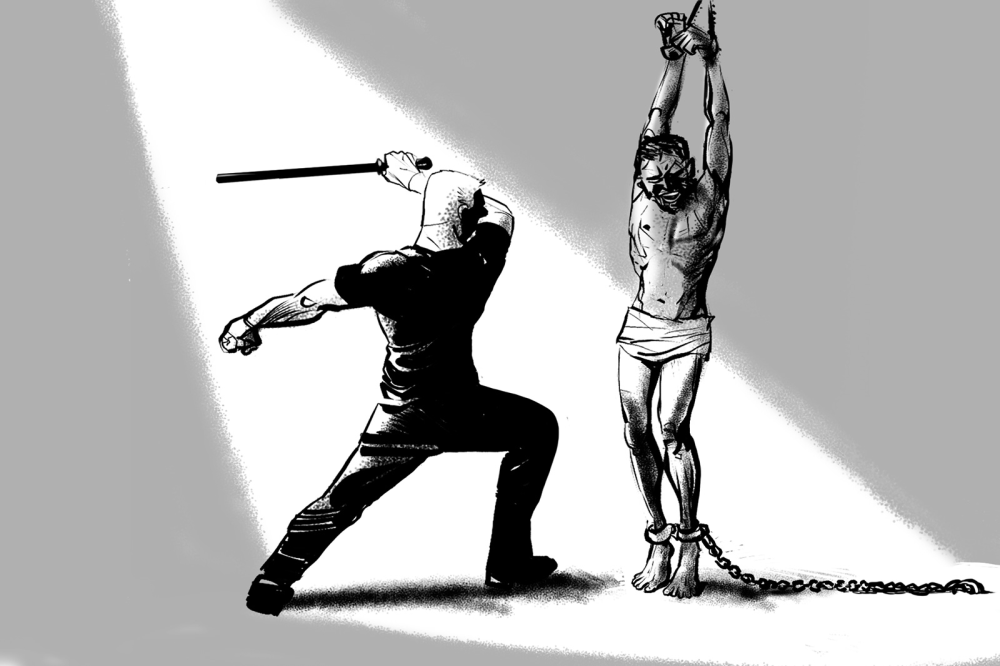

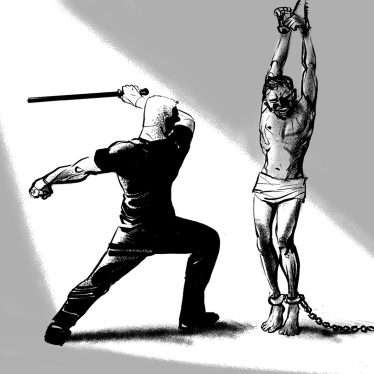

- Both said they were chained to a rod in the ceilings of their cells for repeated 24-hour periods with only short breaks in between for interrogations or other forms of torture. They said it forced them to try to stand, and when they could not, to be suspended from their wrists. They called this technique “hanging” and said it made it nearly impossible to sleep. Sometimes their feet could touch the ground, at other times only their toes. Al-Najjar said that sometimes his feet could not touch the ground at all. Al-Najjar described this period of hanging as lasting roughly three months; for El Gherissi it lasted a month.

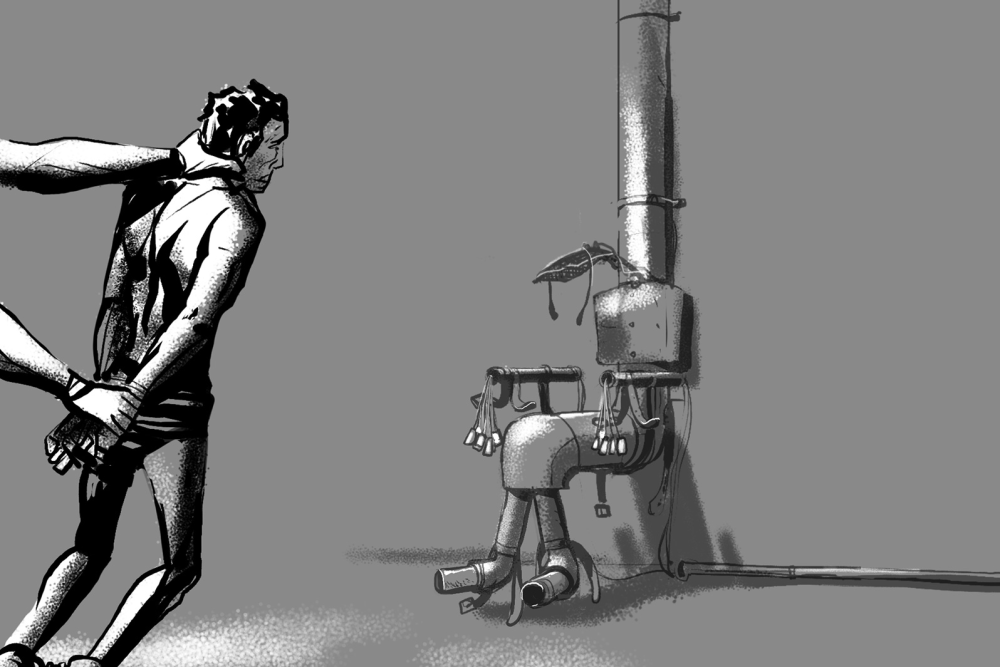

- Both said US interrogators beat them with batons all over their bodies both during and after the hangings; and punched and kicked them repeatedly. Al-Najjar said the beatings resulted in broken bones, which was corroborated by independent medical analysis of his x-rays.

In 2009, US President Barack Obama issued an executive order ending the CIA’s detention and interrogation program and reiterating US adherence to federal and international law banning torture. However, despite ample evidence of criminal activity, the US has yet to conduct a credible criminal investigation into CIA torture, or to prosecute those responsible. Nor has the US offered any form of redress to the many individuals the CIA tortured or otherwise ill-treated.

Human Rights Watch raised al-Najjar’s and El Gherissi’s allegations of torture and mistreatment with the CIA. CIA spokesman Ryan Trapani responded in an email on September 28 that the “CIA reviewed its records and found nothing to support these new claims.”

“The evidence in the public record already warranted criminal investigations into CIA torture but these new allegations further heighten the need for justice,” Pitter said. “This administration has rejected the use of torture, but future administrations will carry the stain of torture until those responsible are prosecuted and the victims compensated. So long as they are confident they won’t be prosecuted, US officials may again resort to torture.”

For the men’s detailed accounts and comparisons with the Senate Summary and other documentation, please see below.

Detailed Account by Ridha al-Najjar

Abuses at the ‘Dark Prison’

Al-Najjar said that upon his arrival at the Dark Prison, his captors stripped off his clothes, threw him down on the cold concrete floor naked, and threw water on him. It was pitch black but several interrogators, including an Arab man with an Egyptian accent came into his cell with a flashlight. One of them cocked a gun to the back of his head and said if he did not talk, they would kill him. They began to beat and kick him and then hung him up on the bar for the first time. The torture sessions after that increased in length as time went on. They showed him documents and photos, and questioned him about his associations and for information about specific attacks. Another interrogator who he said frequently abused him at this facility called himself “Adel.” Al-Najjar said Adel was Shia, Lebanese. He was tall and had a scar on the right part of his lower lip.

Hanging, Beating

Al-Najjar said he was forced to hang from the bar repeatedly over the course of roughly his first three months at the Dark Prison. Each hanging session lasted up to 24 hours and happened frequently and repeatedly. During these sessions his arms would be chained above his head to a bar at the top of the room, making it impossible to sleep. Sometimes he could touch the ground with his feet, sometimes with just his toes, and other times not at all. The captors would only take him down for interrogation sessions and other forms of torture, often by throwing him violently to the floor where they would sometimes beat and kick him. While his arms were chained to the bar, they beat him with a baton on his back and legs and also punched him in the chest, in the back, and in his kidneys. After one session, they took him to another room where he said they used bright lights to videotape and photograph his injuries. “I was a mess,” he said. “I had skin hanging off me and bruises and cuts all over me.”

Water Torture

The US Attorney General approved waterboarding in July 2002. In August 2004, the CIA got “advice” from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) that so-called “water dousing” would not violate the US federal Torture Statute, though the OLC did not officially approve “water dousing” for use as an “enhanced interrogation technique” until 2005. The Senate Summary confirms that the CIA used various abusive techniques with water on at least several detainees without prior Justice Department approval and in ways not authorized. Al-Najjar told Human Rights Watch about several ways his US interrogators used water to torture him:

- When being forced to hang from the bar, a strong stream of water would be directed painfully onto his head for long periods.

- Interrogators would strap him onto a board that they spun around 360 degrees, disorientating him and making him dizzy. Other detainees have provided similar accounts of the CIA using a board to spin detainees fully around. They would throw buckets of extremely cold water all over him while he was strapped to the board, sometimes while he was lying flat and other times while his feet were elevated and his head tipped back. They did not pour the water directly over his face but the water would get into his nose and mouth until, as he said, “I couldn’t breathe anymore and felt like I was suffocating.” Other detainees have reported similar types of abuses with water on a board as well.

- Interrogators strapped him to a board and put him in a tub of extremely cold water and then turned the board over so that his head and body were face down in the water and he couldn’t breathe.

- He was placed in a large tarp full of cold water that he estimated was 70 by 70 centimeters and that zipped at the top. They would place him inside the tarp with only a small amount of room at the top and his captors would push and shove him around while he was inside, making it very difficult for him to breathe.

- His interrogators placed him in a big barrel of water, forcing his head underwater to the point where he could not breathe. Then they would pull him up and ask him questions. “They would do this until I couldn’t handle it anymore and I was on the verge of completely falling apart,” he said.

Role of Medical Professionals

Al-Najjar said that three or four times, he saw a doctor at the facility who treated his lacerations, measured his swelling, and at times gave him injections. After a couple of days, these injections reduced the swelling but then, he said, the hanging and the beatings would start all over again. This doctor would come in before and after the “bad” torture and give the green light to go ahead, he said. He considered the doctor a traitor, because he would come in and treat him for torture but then give a “green light” for new torture sessions.

Other Locations

In addition to the Dark Prison, al-Najjar was held in three other locations in Afghanistan before being transferred to US military custody. He is not sure how long he was held in these facilities.

Intelligence 2

When al-Najjar was first transferred to CIA custody from Pakistan on June 6, 2002, he was initially held at a place he believes was in the Afghan capital, Kabul, that his captors called “Intelligence 2.” He was held in an underground cell, which he determined because there was a window at the top of the cell from which he could see people walking and cars driving by. He said that his captors occasionally took him for interrogation to another house, in a neighborhood called Wazir Akbar Khan. He was not mistreated badly at Intelligence 2 – no beating, just a slap in the face or an occasional kick in the foot or leg.

“This place was nothing compared to where they took me next [the Dark Prison],” al-Najjar said. “Compared to that, this place was like a five-star hotel.” He is not sure how long he was in Intelligence 2, but the Senate Summary says he was the first prisoner brought to Cobalt in September 2002.

He said he will never forget his last day at Intelligence 2 because it was “the worst experience of his life.” He said the same Arab interrogator who spoke with an Egyptian accent who he later encountered at the Dark Prison came to his cell demanding information about documents and photos. When al-Najjar could not provide the answers the interrogator wanted, he became angry and warned that if al-Najjar did not “talk,” he said, “wait until you see what happens to you where we take you next. At the next place we will hang you from your anus.”

After this threat, the interrogators forced al-Najjar to bend over and then chained his arms to the bottom of his legs and placed chains all over his waist, wrists and the rest of his body. They put a bag over his head and something over his ears to prevent him from hearing. They also put something in his anus, which he said they did every time they moved him from one place to another. He said he still suffers pain as a result of these insertions. Many other former detainees have reported having objects, such as suppositories, placed in their anuses during transportation while in CIA custody. “Then they carried me upstairs like a package” and transported him to the Dark Prison, he said.

Panjshir Valley

After his detention, for what he believes were many months, at the Dark Prison, al-Najjar was transferred to a third location that he understood to be in Afghanistan’s Panjshir Valley, 150 kilometers north of Kabul. Conditions in this prison were better. The prison had wooden doors so light could come in. His cell was tiny, approximately 0.8 meters by 2 meters. He said it did not feel as secure. “You had the sense that you could escape but then where would you go?” The cell had a dirt floor and there were lots of insects. They gave him a light blanket full of holes the thickness of a towel. A doctor at this location told him that because of his condition, the officials would not allow him to be tortured anymore.

Kabul II

After the Panjshir Valley prison he was taken to another location in Kabul, in a building that he thinks was part of the “high courthouse.” He said he was held in a number of places inside, on different floors, and was moved underground when other people were in the facility. He was there until his captors transferred him to US military custody at Bagram.

Bagram

Al-Najjar was not sure exactly when he was transferred to Bagram but he believes it was sometime in May or June 2004. Though abusive treatment continued, it was not as bad as it was in CIA custody. At Bagram, doctors, in addition to apologizing for his torture and taking the X-rays and CT scans he described, offered to perform arthroscopic surgery on his damaged knee, which he ultimately refused, afraid that it might cause more damage. He was transferred to Tunisia 11 years later, on June 15, 2015. Because of time constraints, Human Rights Watch did not discuss with al-Najjar the details of his mistreatment while he was detained at Bagram.

Detailed Account by Lotfi al-Arabi El Gherissi

Abuses at the ‘Dark Prison’

El Gherissi said he is not sure of the exact date but several weeks after his initial arrest in Pakistan in late September 2002, he was taken to the Dark Prison. He said his US captors stripped off his clothes, threw him on the floor, and threw cold water on him. The next day they took him to another very small room, about 1 by 1 meter, where he stayed for about a month.

During his entire time at the Dark Prison, music blared 24 hours a day and it was pitch dark. His captors never took him outside, and he never saw sunlight. The only time he saw light was when they came to him with projectors to show him photographs or would shine the bright light of the projector into his eyes while they asked him questions. He knew there were other prisoners because he could hear their screams but he never spoke to them.

Hanging, Beating

El Gherissi said his captors chained him by his arms to a metal rod above his head that went across the ceiling of the room. At the same time, they chained his feet to the ground with heavy shackles that he said were painful. He stayed in this room and in this position, with his arms hanging from the metal rod, for nearly his entire first month there. Sometimes his feet could touch the ground and other times he could only stand on the tips of his toes. While he was hanging, the guards would beat him on his back, legs, and feet with a baton that he believes was made of plastic. They would also throw buckets of cold water on him. This would happen about three times a week. The guards would enter his room, announce that it had been another 24 hours, and then take him down and take him to another nearby room for questioning, he said. When they did this, they would tie his hands with electrical wire. This and the handcuffs caused bad lacerations. A Human Rights Watch researcher saw the scars El Gherissi said he still had from the wires and the chains on his wrists.

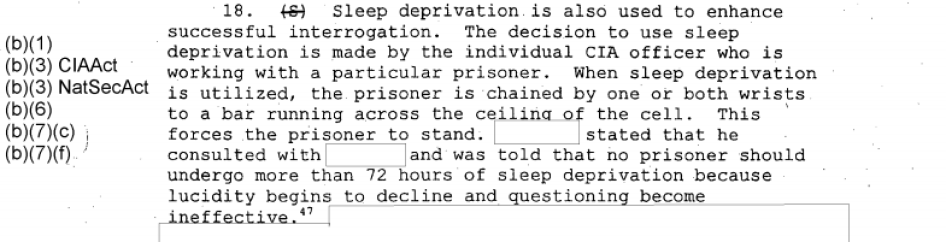

The questioning, which he said often involved accusing him of being a member of Al-Qaeda and demanding information about terrorist plots, usually lasted about 30 minutes, after which the guards would take him back to what he called the “hanging room” and attached his chained hands to the metal bar again. He said they beat him repeatedly, sometimes to the point that he would vomit or faint. Once every two or three days his guards would give him food, which usually consisted of Afghan rice and a bottle of water – though sometimes they would take the bottle away before it was empty. They would not allow him access to toilet facilities. Instead they put a diaper on him and would change that about every three or four days. He was prevented from sleeping. Sometimes he would pass out or faint and guards would come in and wake him up.

El Gherissi said after a month, they took him to another room where he was chained, still diapered, to a wall by his arm. From there they would take him out of the room for questioning and torture.

Electric Chair

El Gherissi said that about three days after they took him down from hanging for a month, they took him to a room with an “electric chair” in it, among other types of torture instruments. He said the chair was made of metal, or perhaps iron. It had clips with wires attached to it intended to be fit on fingers, and a helmet with wires. His description suggested something makeshift, attached to a pipe that came out of a wall. His interrogators put him in the chair and threatened to use it on him unless he gave them more information, though they did not. He said this terrified him and he was trembling. The room also had a board that they threatened to put him on, but never did. He said he understood that water would be used on him while he was on the board.

Abuses with Water, Beatings

During his time there, his captors took him to a room with a tub of water. Guards standing behind him would push the back of his head into the tub, forcing him to stay under water for a minute or two, during which it was impossible to breathe, he said. They did this about three times a day for one week. Also during this time, which was in the winter, they took him to the showers about three times and doused him with cold water that left him shivering.

El Gherissi said that at many different points during this four-month period, his captors beat him. Once, guards came and punched him heavily, breaking two of his teeth. He showed a Human Rights Watch researcher the empty spaces in his mouth. Another time, two guards held him from behind while another was strangling him.

Role of Medical Professionals, Isolation

El Gherissi said that during his time in the Dark Prison, one doctor came to examine him about three times. They did not speak during these exams. Once the doctor gave him aspirin and a vitamin pill. The doctor also checked El Gherissi’s wounds and treated the irritation caused by the infrequent change of his diaper as well as the area where the diapers were taped to his skin.

He said that after four months he felt nearly dead. He did not have any energy and could not think or remember anything. He felt pain all over his body but especially in his back. He lost some of his vision. He said a doctor told his interrogators that, “If he stays for another week, he will die.” At this point the torture stopped. He was then put in another room, in total isolation, for another two months, which actually made him feel worse. “This is when I totally lost it,” he said. “I didn’t have a chance to talk to anyone.”

Other Locations

Kabul, Panjshir Valley

El Gherissi said that after approximately six months in the Dark Prison, he was transferred to an unknown location in Kabul and then brought to a prison in the Panjshir Valley. He was held in a 1.5 by 1 meter room. He said that the conditions were better than in the Dark Prison but still not good. His cell had a dirt floor and his captors gave him a thin cover to sleep on. He was fed more regularly. He spent about seven to eight months there, but he is not sure about the exact amount of time or much of what happened to him. By then he was very sick and tired and had “completely lost my mind,” he said. Doctors would come about once a month, checking his pulse, wrists, and blood. El Gherissi said he believes one doctor whom he saw about three times in Panjshir was the same one he saw at the Dark Prison. He said that he remembers that there were some Pakistani prisoners in the same location but he does not remember talking to them.

Bagram

El Gherissi said that after Panjshir Valley he was taken to Bagram along with an Afghan detainee. The prison conditions were better there than in the Dark Prison, but still not good. In November 2003, he had his first contact with the International Committee of the Red Cross, which brought him the first news about his family. He learned that his wife, who had been pregnant when he was apprehended, had a daughter but she died soon after birth. While he was still detained, after years in US custody, his wife divorced him.

At Bagram, he was initially held in total isolation for 40 days and then was put in a big cell with 30 other detainees. The facility had 16 cells, each with about 30 people. “Still, you were not allowed to speak to any other detainees,” he said. “If you did, you would be punished.” One of the ways the guards punished him was by ordering him to hold his arms out from his sides for extended periods. If he could not do that, the guards placed him in isolation. They also frequently brought in dogs that terrified him, he said. Each week he would be interrogated by people he said were US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents.

Health care was better at Bagram because there was a medical clinic. But the guards here also tried to deprive him of sleep. Someone would wake him at least three times a day and twice at night. The food was also still entirely inadequate, he said: “They didn’t feed you enough to fight the hunger.”

In 2010, he was moved to a new prison and conditions improved. Because of time constraints, Human Rights Watch was not able to discuss with El Gherissi many details of his mistreatment while he was detained at Bagram. The US transferred him to Tunisia on June 15, 2015.

New Accounts Add Details of Torture Missing from Senate Summary

The Senate Summary states that the CIA held al-Najjar for between 690 and 700 days and El Gherissi for between 380 and 390 days before transferring them to US military custody at Bagram airbase, where they both spent more than a decade.

Al-Najjar and El Gherissi are the first detainees to report on what conditions were like at Cobalt before Gul Rahman’s death. A partially redacted summary of an investigation into Rahman’s death, dated January 28, 2003, but only released in June, states that Rahman, like other detainees, was subjected to numerous abuses, including standing sleep deprivation, “water dousing,” exposure to cold temperatures, and “rough treatment,” but concludes that there is “no evidence” to suggest that Rahman was beaten or tortured. It finds the ultimate cause of death was most likely hypothermia, partially caused by Rahman “throwing his last meal” and therefore denying his body “with a source of fuel to keep him warm.”

The Senate Summary states that CIA records at Cobalt were poorly kept and that “the full nature of CIA interrogations” there “remains largely unknown.” For example, there are no records of any detainee being waterboarded at Cobalt, yet Senate investigators found a photo in CIA records of a wooden board there surrounded by buckets, with a bottle of unknown pink solution (filled two-thirds of the way to the top) and a watering can resting on the wooden beams of the board. Senate investigators also found that the CIA subjected detainees at Cobalt to numerous techniques not recorded in CIA cable traffic, including “multiple periods of sleep deprivation, required standing, loud music, sensory deprivation, extended isolation, reduced quantity of food, nudity and ‘rough treatment.’”

The Senate Summary, which draws from the CIA’s own records, does not spell out in detail the CIA’s treatment of al-Najjar, but documents the CIA’s planned interrogation methods for him once he was moved, in September 2002, to the Cobalt detention site. This included threatening the “well-being of his family,” using “sound disorientation techniques,” denying him sleep using round-the-clock interrogations, depriving him of any “sense of time,” keeping him in “isolation in total darkness; lowering the quality of his food,” using cold temperatures, playing music “24 hours a day, and keeping him shackled and hooded.”

On September 21, 2002, a CIA cable described him as a “clearly broken man” and “on the verge of a complete breakdown.” Despite this assessment, the CIA continued to torture al-Najjar. The Senate Summary states that a US military legal adviser visiting Cobalt in November noted that al-Najjar was left hanging, handcuffed to a bar above his head, unable to lower his arms, for 22 hours each day for two consecutive days. The adviser noted that al-Najjar was wearing a diaper and had no access to toilet facilities.

Al-Najjar’s account of his treatment in CIA custody indicates that it was worse than the Senate Summary described.

The Senate Summary has very little information about El Gherissi, whose name is spelled as “Lufti al-Arabi El Gharisi.” His name appears twice, once on the list of 119 detainees the CIA admits to holding as part of its “enhanced interrogation program,” and another time when it states that El Gherissi was one of 17 prisoners the CIA subjected to techniques without the approval of CIA headquarters. In a footnote, it states that El Gherissi "[u]nderwent at least two 48-hour sessions of sleep deprivation in October 2002."

Failure to Provide Redress

The Senate Summary conservatively estimates that approximately 119 detainees were officially in CIA custody, al-Najjar and El Gherissi among them, though that figure does not include many more whom the CIA is believed to have transferred to other countries to be interrogated and tortured. Of the 119, 14 remain in US custody at the Guantanamo Bay detention facility, but the vast majority have been released. The US is not known to have compensated any of them.

Though some former CIA detainees have filed lawsuits in US court seeking redress for their mistreatment, nearly every case thus far has been dismissed before the courts have examined the merits of the claims. Often the courts have asserted the state secrets privilege, which the US government has argued should apply, claiming that litigating a case will reveal state secrets that will harm US national security. For the most part US courts have deferred to government claims about potential harm. Earlier in 2016, in the first suit since the Senate Summary’s release, brought by the American Civil Liberties Union on behalf of three former detainees held by the CIA, the Justice Department for the first time did not assert the state secrets privilege to block the suit.

Under international human rights law, notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture, both of which the US has ratified, governments have obligations to ensure the right to an effective remedy for victims of serious human rights violations, including torture and other ill-treatment. A victim’s right to an effective remedy requires the government to take the necessary investigative, judicial, and reparatory steps to redress the violation and provide for the victim’s rights to knowledge, justice, and reparations. The government is under a continuing obligation to provide an effective remedy; there is no time limit on legal action. Although these violations did not take place in the United States, they occurred while the individuals were under the effective control of US security forces.

Post-Release Experiences in Tunisia

Both detainees said that neither the US nor the Tunisian governments have provided them with assistance – medical, psychological, or financial – to help them resume their lives or integrate back into society. They both live with their families in small quarters and are completely dependent upon them for help. “My sister has five kids,” al-Najjar told Human Rights Watch. “I’m the sixth.” He was still wearing some of the clothes the US government gave him before he was released, which had holes in them. El Gherissi lives in a house with his elderly mother, brother, and sisters that has no doors or even a full roof.

Al-Najjar was released from custody after being briefly held by Tunisian authorities. He told Human Rights Watch that he has a number of physical problems that have hindered his ability to find work, notably chronic pain associated with a broken ankle, hips, and backbone. He has blood in his stool, a swollen liver, kidney pain, a hernia, an ulcer, and a “hole in his ear” that he said is a result of being tortured. He also said he feels a sharp pain in his head whenever he tries to remember anything about the abuses he endured in CIA custody.

Without resources, he has not been able to obtain medical treatment in Tunisian hospitals. Since June, he has gone to a torture survivor’s center in Tunis that he said is helping facilitate some medical treatment and tests for his injuries, but this still requires funds for travel, tests, and medications. He said he would like to work buying and selling goods but the Tunisian government has not provided him with the papers that would allow him to travel. He said he is very depressed because he cannot bear being a burden on his family but also cannot seem to find a way out of his situation.

El Gherissi was released almost immediately after being transferred to Tunisian custody. He is currently living with his brother and his five children in Gabes, about a five-hour drive from the capital, Tunis. Also in the same house are his three sisters, their children, and his elderly mother, with whom he shares a room and a bed. His brother’s house is just a bare structure with unfinished walls and doors. There is no full roof, and it leaks. The front entrance has no door, just a sheet that covers the opening.

He said he is very poor and has no means to support himself. He has chronic pain in his back and knees, which prevent him from sleeping. He also cannot see very well and has blurred vision. He has not been able to see a doctor because he cannot afford one. He cannot find work due to his physical ailments and relies on his relatives for help, which depresses him deeply. He hoped to change his life by getting healthy, starting a family, having his own home with a roof over his head, going back into the trade business, and having friends and being social. But he feels helpless and unable to do any of this now.