The United States government just opened the door a crack to justice for the torture of scores of men in CIA custody under its infamous detention and interrogation program. For the first time, the Justice Department didn’t effectively block a lawsuit by detainees held and tortured by the CIA by invoking, as it had done in previous similar lawsuits, the “state secrets privilege.”

The privilege requires a court to give great deference to a government claim that litigating a case would risk revealing state secrets that would jeopardize national security. That claim put an end to previous cases related to the torture program, hindering victims’ efforts to secure redress, and keeping a tight lid on details about the program. For years, Human Rights Watch has urged the administration to stop invoking the privilege unless it was truly necessary to protect genuine national security interests.

In this case, Salim v. Mitchell, a federal judge allowed the lawsuit to move to the next phase. It was brought by Suleiman Abdullah Salim and Mohamed Ahmed Ben Soud (formerly Mohammed Shoroeiya), two now-free, former detainees of the CIA who were never charged with crimes by the US, and the family of Gul Rahman, who died in CIA custody after being tortured in Afghanistan. (Human Rights Watch first published Shoroeiya’s account in a 2012 report.)

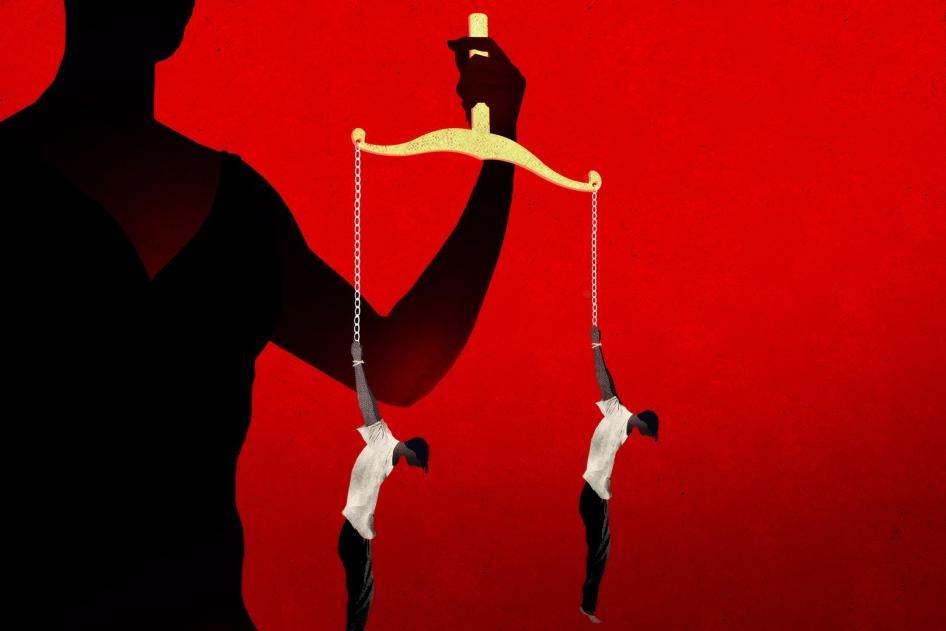

The plaintiffs, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union, are suing Bruce Jessen and James Mitchell, psychologists whose company was paid $81 million under CIA contract to develop and implement the CIA’s interrogation program. The Justice Department’s decision not to invoke the privilege probably resulted, in part, from the release of the summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee study on the CIA’s program in December 2014. With so much information now in the public domain, it is harder to claim that litigating the case would reveal harmful state secrets. Still, the administration deserves credit for not attempting to make that argument.

The plaintiffs will face many further obstacles. The defendants may claim they can’t defend themselves without bringing in still classified evidence, so the government could invoke the privilege at a future stage. And civil redress is no substitute for thorough and credible criminal prosecutions that the US government is required to bring in accordance with its international treaty obligations. But for the time being, the administration’s position provides hope that at least three of the scores of CIA torture victims might one day actually get their day in court.