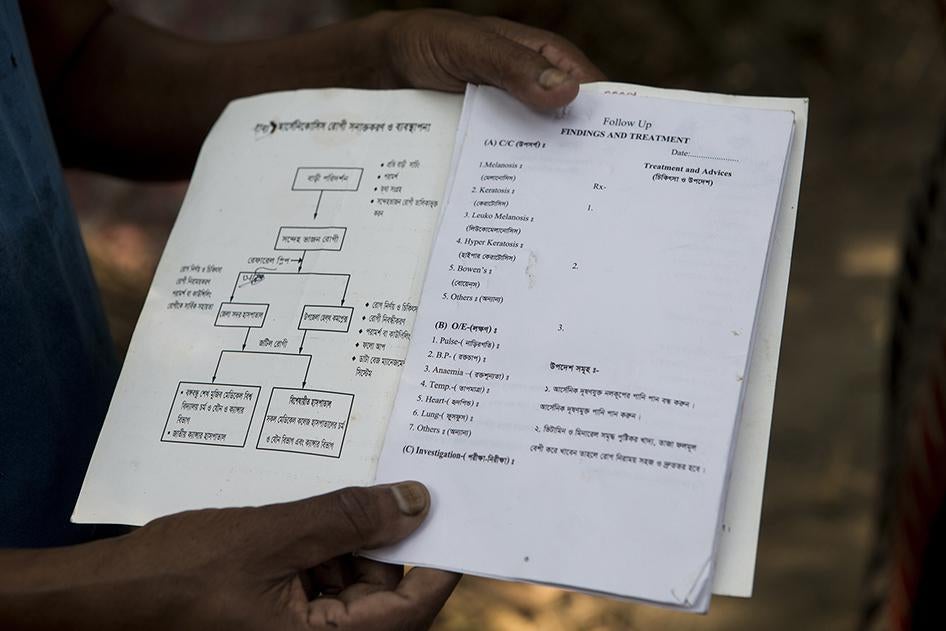

Human Rights Watch interviewed 134 people for the report, including people suspected of having arsenic-related health conditions and caretakers of government wells in five rural villages, as well as government officials and staff of nongovernmental organizations. It also analyzed data regarding approximately 125,000 government water points installed between 2006 and 2012 (constituting the overwhelimg majority of government water points installed during this period).

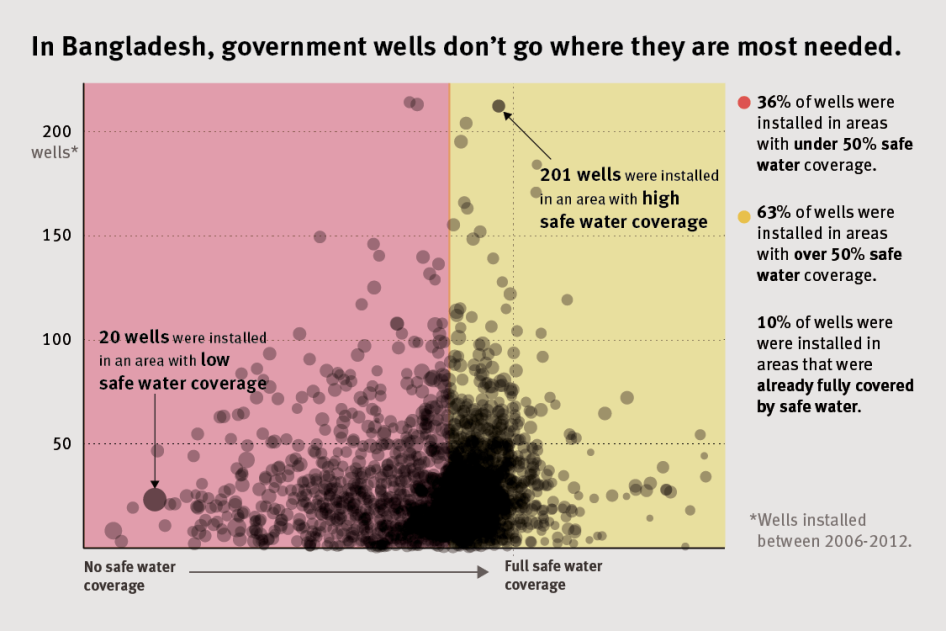

Arsenic is found in water from hand-pumped, mostly shallow, tube wells across huge swaths of rural Bangladesh. Although deep wells can often reach groundwater of better quality, government programs to install new wells don’t make it a priority to install them in areas where the risk of arsenic contamination is relatively high.

Moreover, some national and local politicians divert these new wells to their political supporters and allies, instead of the people who most need them.

“If the member of parliament gets 50 percent [of the new allocation] and the upazila [sub-district] chairman gets 50 percent, there’s nothing left to be installed in the areas of acute need,” explained one government official who spoke to Human Rights Watch on condition of anonymity.

Human Rights Watch also found a serious lack of monitoring and quality control in arsenic mitigation projects. In a small but significant number of cases, some new government wells are themselves contaminated with arsenic above the national standard. A Human Rights Watch analysis of government data found that 5 percent of the wells reviewed were contaminated above the Bangladesh standard.

The World Bank, which funded the installation of approximately 13,000 rural wells from 2004 to 2010, should promptly and thoroughly investigate whether they are contaminated and, if they are, replace or rehabilitate them. Bangladesh’s international donors have an important role to play, and they should do more, but with more care, Human Rights Watch said.

In 1995, an international conference in Kolkata helped draw the world’s attention to the problem of naturally occurring arsenic in the groundwater across huge swaths of rural Bangladesh. From 1999 to 2006, the government, international donors, and nongovernmental organizations oversaw a concerted effort to mitigate arsenic contamination in Bangladesh’s groundwater.

Under the national well screening (the bulk of which occurred from 2000 to 2003) some 5 million wells across the country were tested with field kits and the pumps painted red or green according to whether they were above (red) or below (green) the national standard. The screening found that wells of an estimated 20 million people yielded water with arsenic above 50 micrograms per liter (the national standard).

Since 2006, however, the urgency of such efforts has dissipated. A nationwide study of drinking water quality in 2013 found a similar result to the earlier screening, a rate of contamination that corresponds to some 20 million people exposed to arsenic above this level.

“Bangladesh should not allow national and local politicians to divert these life-saving public goods to supporters and allies,” Pearshouse said. “Contaminated government tube wells urgently need to be replaced or rehabilitated, before people lose what little faith they have left in the government’s commitment to provide safe water.”

Statements by people interviewed:

“When it comes to arsenic problems they usually say, ‘We have nothing for your illnesses.’”

–Nouka, a woman living in Balia village with black spots on her shoulders, arms, palms, and the back of her hands

“I’ve never been to a hospital, I’ve never seen a doctor. I take no medication. No one from the government has ever told me anything about arsenic or that I suffer some effects of arsenic poisoning.”

–Astha, a woman in her 40s living in Ruppur village, suspected of having arsenic-related health conditions

“There are no government-installed water sources in this area. Look at my children! Even if we feed them as best we can and look after them well, they will fall sick from arsenic in the water.”

–Khobor, a farmer in his mid-30s in Bilmamudpur village, with arsenic-related skin lesions on his chest and feet

“It has been at least 10 years since arsenic people came from the government to conduct tests and paint the tube wells red or green [to indicate which were above or below the national standard]. I wish they’d come back and do their job properly.”

–Agrahayan, a man in his mid-50s who lives in Ruppur village, suspected of having arsenic-related health conditions

“There are no government-installed tube wells in this village. They installed one in the nearby school but it hasn’t been working for years. They don’t give them to us but I don’t know why. I don’t know who to ask or how to ask.”

–Janala, a woman in her 40s living in Ruppur village, suspected of having arsenic-related health conditions

“Many government tube wells are installed in private homes; the owners bribe government people or use their political connections. We don’t even know where some of them are, they’re so secretive. It makes me very angry to think about this.”

–Khaddro, a farmer in his 30s living in Ruppur village, suspected of having arsenic-related health conditions

“Site selection of new tube wells is essentially all about politics. They give them to their political allies, their supporters, those close to them or those who work for them. It is very frustrating, they don’t consider the real needs of the people.”

–Anonymous government official

“Six people from my household drink from this well. We don’t let others drink from it. My father-in-law is a friend of the upazila [sub-district] chairman. They are in the same political party, so they have a political friendship. We paid 30,000 taka (approximately US$390) to the upazila chairman.”

–Anonymous caretaker of a government tube well