Secretary of State John Kerry called the collapse of the latest round of Israeli-Palestinian peace talks “reality-check time” for the peace process. That reassessment should include the self-defeating U.S. policy of opposing steps toward justice and accountability in the name of negotiations.

U.S. officials claim that the International Criminal Court (ICC) poses a danger to peace talks and are pressuring Palestinians to forego asking the ICC to take jurisdiction over serious crimes by all parties committed in or from Palestinian territory. But those who support negotiations should realize that the greater danger to peace is impunity for serious crimes.

The U.S. position bolsters those who dismiss the ICC as “an empty gun” – as the pro-settlement Israeli economy minister, Naftali Bennett, wrote in an opinion piece last month. The Palestinians, he wrote, will never succeed in stopping Israeli settlements – which the U.S. opposes, and which violate the ICC statute as well as the Fourth Geneva Convention – even if they “go to The Hague.” Bennett is confident that “the international community” will oppose such a move, which would open “a political Pandora’s box,” and that the Palestinians will ultimately back down out of fear that the ICC would examine crimes committed by their side, such as rocket launches by armed groups in Gaza that harmed Israeli civilians.

In fact, as 17 Palestinian and international rights groups pointed out in a recent letter to the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, Palestine should go to The Hague precisely because the ICC could impartially mete out justice for serious crimes by all parties – whether settlements, illegal attacks on civilians, or torture – and potentially deter more of them.

Yet last month, the U.S. even opposed Palestine’s accession to human rights treaties that would increase pressure to end torture by Palestinians – because it was a move taken outside the negotiations framework. In 2013, the official Palestinian rights ombudsman’s office registered 497 allegations of torture by Palestinian security forces – up from 294 in 2012. There were no criminal prosecutions.

Similarly, the U.S. opposition to the settlements as an “obstacle to peace” should lead it to support Palestinian access to the ICC, whose statute, reflecting the Geneva Conventions which Israel has ratified, forbids the transfer of civilians by an occupying power into occupied territory. On settlements, the U.S. negotiations-only policy has clearly failed.

In January 1988, when there were 180,000 settlers, the U.S. vetoed a Security Council resolution calling on Israel to abide by the Geneva Conventions. The U.S. said the resolution touched on “issues which are, at this time, best dealt with through diplomatic channels.” In veto after veto after veto, the U.S. argued that resolutions criticizing settlements “could encourage the parties to stay out of negotiations.” Today the settler population stands at more than 540,000.

Israel’s settlements policy is not an abstract problem, endlessly open to resolution in the future. Settlers have gone unprosecuted for thousands of attacks on Palestinians and their property and taken over Palestinian homes, farmland, and water springs. They enjoy subsidies, special infrastructure, and almost six times as much water per capita as Palestinians. At the same time, Israel restricts Palestinian access to farmland, and virtually prohibits Palestinian housing construction, in the 62 percent of the West Bank under its exclusive control, known as “Area C.”

Discriminatory Israeli restrictions mean that at night, some Palestinians light candles while watching people turn on the lights in settlements next door. Palestinians who want to marry and raise families have had to move away from their villages because the Israeli military will not give them permits to build or expand homes.

These bitter experiences don’t make peace negotiations any easier. Yet during the latest round of peace talks, which began last July, the U.S. pressured Abbas to delay seeking ICC jurisdiction for nine months. In that time, Israel promoted plans and tenders for at least 13,851 new settlement housing units, the Israeli group Peace Now reported, and demolished the homes of 878 Palestinians, according to data collected by the UN. A report by European diplomats on developments in East Jerusalem in 2013 noted “an unprecedented surge in settlement activity” since “the resumption of the peace negotiations.” A U.S. official told The New York Times that “at every juncture” of the recent negotiations, “there was a settlement announcement. It was the thing that kept throwing a wrench in the gears.”

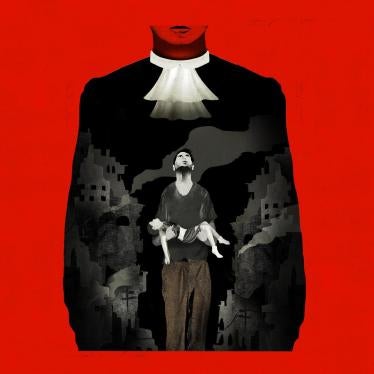

By blocking accountability in the name of advancing the peace process, the U.S. has facilitated the settlements and other war crimes that are undermining the prospects for peace.

The U.S., which has supported ICC jurisdiction in places such as Libya, Sudan, and now Syria, should support it in Palestine. International justice should not be a political game. Justice is an important end in its own right, and a credible ICC prosecution threat could help to advance the cause of peace.

Bill Van Esveld is a Middle East researcher at Human Rights Watch based in Jerusalem.