The resumption of the Juba talks on April 26 renews the chance for an end to the horrific 20 year conflict in the north. But to achieve this much needed peace, the warring parties and the mediators cannot bargain away prosecution of the LRA leaders who have been charged with grave crimes. Simply put, a solution that avoids meaningful justice will undercut the prospects for a durable peace.

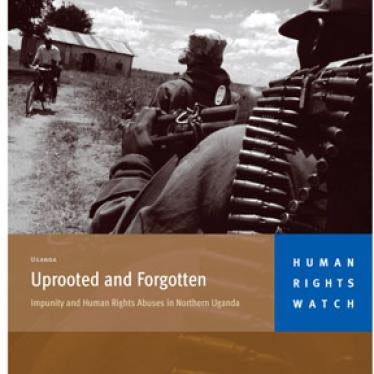

For over 10 years our organisation, Human Rights Watch, has documented widespread crimes committed by the LRA leaders against civilians. The crimes include widespread killings, mutilations, rape, abduction and forcible conscription of children. While lesser in scale, we also documented the involvement of the UPDF in abuses, including beatings, sexual violence, and killings.

Last month we spoke with people who were victims of the massive displacement that occurred in the north due to the conflict. Nearly all those we met in displaced camps expressed an intense desire to return to their homes. A number conveyed real concern that prosecution of LRA leaders could further delay their departure and therefore saw the ICC as an obstacle. A distinct vocal minority, however, declared a desire to see those most responsible brought to trial, although they questioned how the ICC could arrest those it had charged.

International law demands justice for crimes against humanity and war crimes, but the need to prosecute those responsible at the top levels goes far beyond a legal obligation. Handing the LRA leaders associated with the most serious crimes a "get out of jail free card" would have serious consequences for the peace the people of northern Uganda so urgently want.

By issuing its arrest warrants against four senior LRA leaders, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has taken an important step to seeing that justice is done for the crimes committed in northern Uganda.

Not surprisingly, Joseph Kony and Vincent Otti want to avoid trial at the ICC. Indeed, they have made every attempt to barter their signature on a peace agreement for immunity from meaningful prosecution. They have painted the ICC as the obstacle to peace, while minimising their role in the horrible crimes that occurred.

By depicting the ICC as the problem, the LRA leaders are trying to turn reality upside down. It is believed that the ICC warrants were an important factor in getting the LRA leaders to agree to the Juba talks. Moreover, after many victims realise that the crimes against them and their loved ones have been excused, a peace agreement based on impunity for the likes of Kony and Otti would likely prove not to be worth the paper it is printed on.

Of course, the ICC is not the only means through which justice can be achieved. The ICC cases against the LRA leaders could be tried in Ugandan courts. But any national alternative to an ICC trial must demonstrate a genuine ability and willingness to conduct the investigation or prosecution.

Sham national proceedings aimed at shielding the accused from responsibility, unfair trials, or even meaningful prosecutions accompanied by a slap-on-the-wrist sentence will not pass muster with the ICC judges who will ultimately decide whether a trial in Uganda is an acceptable alternative.

The ICC requirements for genuine national trials are necessary to ensure that justice plays its role in providing accountability and promoting stability in an area torn apart by war and displacement. In this situation, fair and credible trials -- of those in both the LRA and the UPDF responsible for the most serious crimes -- with appropriate penalties will send the message that widespread atrocities will not be tolerated, thereby helping to rebuild respect for the rule of law.

There will also be a need for other mechanisms to ensure accountability: trials for lesser offenses, a truth commission, and, where appropriate, traditional justice measures. In addition, northern Uganda will need reconstruction and development assistance.

A peace worth having cannot rest on impunity. It is up to key players such as the UN Secretary-General's special envoy, former Mozambican President Joaquim Chissano to convey this message loud and clear at the Juba talks. Governments also have a key role to play, including the "core group" on Uganda (the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands, and Norway), and the African observers to the talks (Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of Congo).

Those with an interest in seeing a lasting end to the conflict in northern Uganda should insist on an outcome that includes peace and justice. Anything less would be abandonment of the victims, international principle and won't last long.

Elise Keppler is counsel and Richard Dicker is director of the International Justice Program at Human Rights Watch. They recently returned from mission in Uganda.