(Beirut) – Iraq’s environmental activists are facing threats, harassment, and arbitrary detention by government officials and armed groups, Human Rights Watch said today.

On February 16, 2023, leading Iraqi environmentalist Jassim al-Asadi was released after being abducted on February 1 by an unidentified armed group and held for more than two weeks. Al-Asadi said in a TV interview that he was subjected to “most severe forms of torture” using “electricity and sticks” during his captivity, and was moved from place to place. Human Rights Watch confirmed with his family that the voice in the interview is his. It appears he was released after intervention by the Iraqi government. Al-Asadi’s kidnapping is the latest in a string of acts of retaliation against environmental activists apparently intended to halt their advocacy.

“Rather than taking decisive steps to solve Iraq’s critical environmental issues, Iraqi authorities are instead attacking the messenger,” said Adam Coogle, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “Decimating the country’s environmental movement will only worsen Iraq’s capacity to address environmental crises that affect a range of critical rights.”

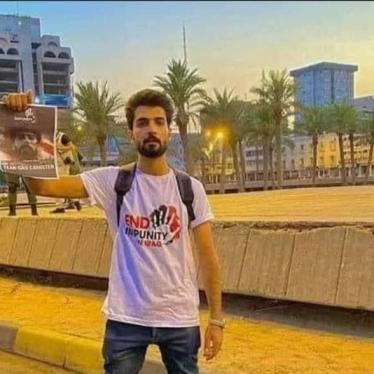

Government agencies have detained and prosecuted other activists for speaking out about environmental problems. Salman Khairalla, another environmentalist and co-Founder of Humat Dijlah (Tigris River Protectors Association), told Human Rights Watch that he believes armed groups and Iraqi officials are targeting key members of the environmental movement to silence them and send a threatening message to others.

In November 2022, Human Rights Watch released a report documenting that Iraqi authorities have failed to ensure any accountability for state security personnel and state-backed armed groups responsible for killing, maiming, and disappearing hundreds of demonstrators and activists since 2019.

Iraqi authorities should immediately hold accountable those responsible for extrajudicial punishments such as kidnapping, stop using the justice system to harass and retaliate against environmental activists, and drop all abusive legal cases against them, Human Rights Watch said.

Al-Asadi’s brother told Human Rights Watch that al-Asadi was driving on the highway with his cousin on the morning of February 1 when two cars stopped him six kilometers south of the capital. Armed men in civilian clothes handcuffed him and forced him into one of the vehicles, taking him to an unrevealed location and leaving his cousin in the car on the side of the road. His brother said he did not know the motivation behind his brother’s kidnapping but that many government backers were not happy about his environmental activities.

Al-Asadi is the founder of the local nongovernmental organization, Nature Iraq, which aims, “to protect, restore, and preserve Iraq’s natural environment and the rich cultural heritage that it nourishes.” Al-Asadi has appeared regularly in local and foreign media outlets to raise awareness of the threats facing the country's southern wetlands, including drought and loss of vegetation coverage.

His brother said that the family reported the kidnapping to a National Security office in Baghdad and Iraqi security forces began investigating the case. The case reached the attention of Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, who assured the family “that there’s no armed force above the law and that everyone is subject to the authority and law of the state.” A few days later, Al-Asadi was released, but the reason for his detention and identity of the kidnappers have not emerged.

Although the Iraqi government appears to have taken steps to intervene and secure al-Asadi’s release, in other cases Iraqi authorities themselves have been responsible for retaliation against environmental activists in response to their efforts to draw attention to human rights breaches linked to the country’s environment and climate.

In late 2019, Iraqi authorities arbitrarily detained Salman Khairalla, another environmentalist, prompting the then-UN special rapporteur on human rights defenders to intervene to demand his release. After Khairalla was released on bail, he left Baghdad.

Another activist, Raad Habib al-Assadi, head of Chabbayish Organization, an environmental organization, told Human Rights Watch that during the 2019 and 2020 droughts that struck Iraq, he criticized the Water Resources Ministry for its poor policies and responses to the worsening water situation. He said that he published basic information about the droughts in the marshes in Nasiriyah, such as how much the water levels were dropping. The ministry retaliated by taking him to court.

On October 5, 2020, Dhi Qar Federal Court of Appeals ordered Habib to appear in court under Article 434 of Penal Code, which criminalizes insulting any person or imputing the reputation of another, and carries a penalty of up to one year in prison and/or a fine.

A court acquitted him in February 2021, but ministry representatives subsequently filed a second case against him, under Article 229 of Iraq’s Penal Code, which criminalizes insults or threats to, “an official or other public employee or council or official body in the execution of their duties or as a consequence of those duties.” This “crime” is punishable by up to two years in prison or a fine.

Habib told Human Rights Watch that the court also acquitted him of the new charges, with the final acquittal coming on December 10, 2022. But ministry officials continue to appeal the acquittal.

Habib said he is forced to attend the appeal hearings to avoid prison and believes that ministry officials are drawing out the case to punish him. “Every Monday and Thursday I have to go to the court [to deal with the appeals],” he said. “But nothing happens when I go to court. I attend and then the appeal is delayed – one week or 10 days or 14 days. But if I don’t attend, the authorities can issue an arrest warrant.”

He said ministry officials have offered to drop the case against him if he pledges to stop criticizing the ministry, but he has refused.

“I did nothing wrong, I only shared information about the droughts in marshes and they treated me as a criminal,” Habib said. “I can’t travel or do anything because I have to go to the court every Monday and Thursday. The ministry officials told me, ‘We want to quiet you.’”

“The Iraqi government’s muzzling of environmentalists who are trying to raise awareness around the country’s grave challenges is part of a broader attitude that sees civil society groups as threats rather than partners,” Coogle said.