If you drive from Cilacap, a port and trading city on the southern coast of Java Island, and head east for 45 minutes, you may spot a sign pointing to Gunung Srandil. The mountain’s name is a combination of the Javanese words “sranane” (must be) and “adil” (just).

Mount Srandil is no ordinary hill with a view of the Indian Ocean. It is also an ancient mystical complex that houses multiple shrines dedicated to Javanese saints and Hindu gods and goddesses, as well as a Buddhist temple and an Islamic mosque.

I visited the compound on a very dark evening in October 2021, with a Javanese guru accompanying me with his flashlight as well as incense and flowers.

His name is Mbah Salio, a caretaker at Mount Srandil.

Mbah Salio told me that the compound is legally the property of the Central Java army command. A notice board says the area is under the supervision of the command’s detachment on arts and property.

“President Soeharto used to be the commander,” he said.

“He often came here to meditate, not only during his [military] service, but also during his presidency.”

We walked around the vast compound, peering into each shrine.

Mbah Salio even urged me to drive to a more remote shrine. Through the dark forest, about 30 minutes from the compound, we reached the Pertapaan Cemara Putih (White Pine Hermitage) in Mount Selok. My car was the only vehicle on that village road.

Mbah Salio asked a guard, who lives nearby, for a key to open the shrine.

Inside the shrine were three cemeteries and a huge painting of the Queen of the South Coast – popularly known as the mystical goddess Nyi Roro Kidul. Mbah Salio lit incense again, saying a prayer in Javanese amid the dead quiet.

He asked me to make a wish.

I said, “Religious freedom and belief in Indonesia.”

He returned to his prayer.

We later drank tea and smoked cigarettes in the guard’s post.

“President Soeharto, when he was still in power, used to have a helipad there,” Mbah Salio said, pointing to an open field. A Buddhist temple stands near the former helipad.

Mbah Salio said he met Soeharto there when he was younger.

I asked him how he would describe Soeharto’s beliefs.

“He’s a Kejawen but he’s also a Muslim, like me,” he said. “I am a member of the Nadhlatul Ulama. I am a card-carrying member.”

Young Soeharto’s Spiritualism

Soeharto was indeed a Kejawen; a practitioner of the Javanese folk religion that marries animism, Buddhist, and Hindu traditions. Though Islam has become the dominant religion on the island since it arrived in the 1500s, traces of Kejawen are still commonly found in the beliefs and practices of modern-day Javanese Muslims.

In 1935, when he was 14 years old, Soeharto moved to Wonogiri, an agricultural town in Central Java, and got to know Romo Daryatmo, a Javanese mystic and faith healer, through his new foster father.

In Wonogiri, a young Soeharto not only enjoyed agricultural life – bathing water buffalos and working on rice fields – but also learned about Daryatmo’s spiritual life.

Daryatmo was a nominal Muslim. He knew the Koran, but more in a Javanese sense than in a conventional Islamic one. As a Kejawen practitioner, he would recite Islamic phrases but did so mostly in Javanese.

Many people in Wonogiri viewed Daryatmo as a man who had mastered arcane disciplines to establish a harmonious relationship with God and someone who was able to draw from his spiritual powers to cure the sick.

Soeharto also found in Daryatmo a missing father figure. He soon became Daryatmo’s disciple, moving into the guru’s house, where he worked as a part-time assistant, preparing his morning coffee and assisting him in writing prescriptions for herbal medication. It was a formative period that gave Soeharto valuable insight into Javanese philosophy and shaped his world view.

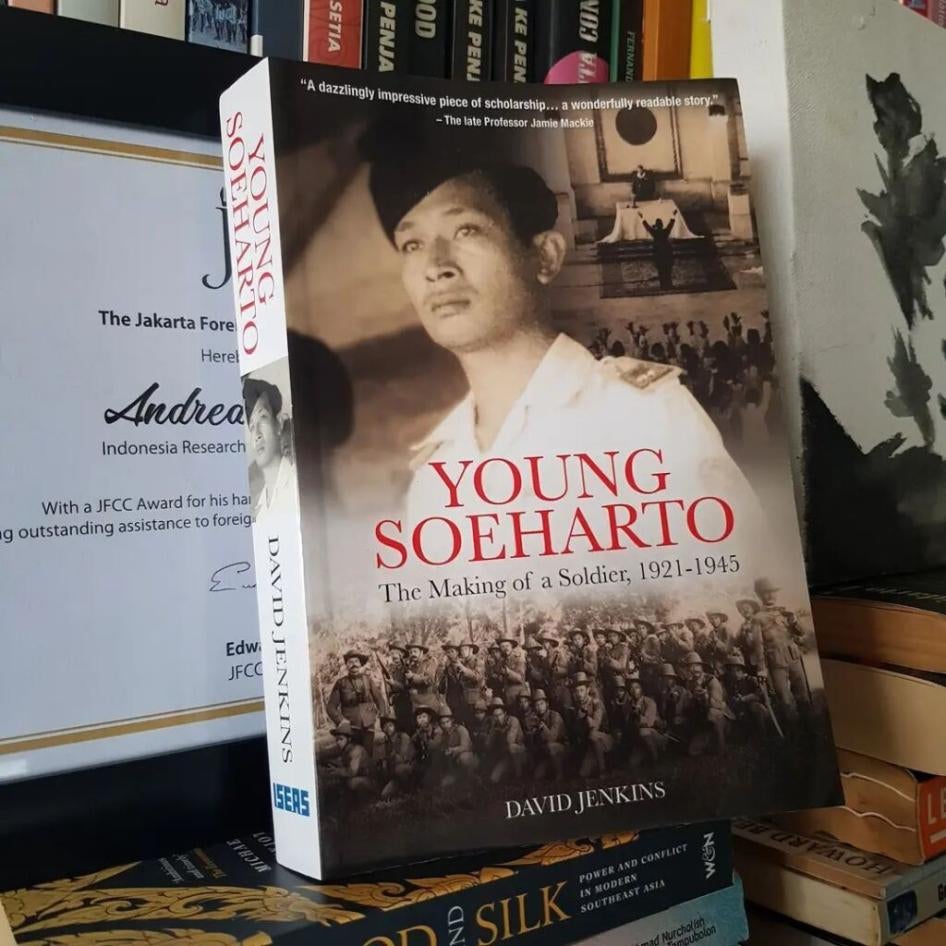

David Jenkins’ new book, Young Soeharto: The Making of a Soldier, 1921-1945, delves into the early life of Indonesia’s authoritarian ruler, who stayed in power for 33 years, also arguably the strongest. What emerges from the details is the story of the man who was not just a Muslim but also an ardent adherent to Kejawen in a country that has become increasingly Islamized over the last three centuries.

In his 1989 autobiography, Soeharto: My Thoughts, Words, and Deeds, written by G. Dwipayana and Ramadhan K.H, Soeharto refers to Daryatmo as a kiai, an old Javanese word for a spiritual man. When Soeharto was in power, between 1965 and 1998, he called Daryatmo at least once a week and practiced Kejawen himself.

Jenkins’ book is essential because it details Soeharto’s Kejawen upbringing and his Japanese military training during their occupation on Indonesia from 1942 to 1945.

Major General Soeharto rose to power in 1965 during a period of mass killings by the military, paramilitary groups, and Muslim militias. US diplomatic cables from Jakarta documented tens of thousands of killings of suspected Communist Party members, ethnic Chinese, as well as trade unionists, teachers, activists, and artists. Soeharto ruled Indonesia with the military’s backing, repressing opponents, seizing naturally rich lands, and abusing people’s rights.

In 1975, when President Soeharto was considering an invasion of Portuguese Timor, he flew from Jakarta to the Dieng Plateau, another mystical site for ancient Javanese rituals. He brought his guest, Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, to a secret cave where Soeharto sought to receive spiritual wisdom. He decided to invade Portuguese Timor after receiving support from Whitlam, as well as US President Gerald Ford, who he met in Jakarta. The invasion had well-known, tragic human rights consequences for the Timorese people.

Giving in to Islamists

David Jenkins’ book also reveals an important aspect of Soeharto’s view of Islamists. During the 1977 general election, President Soeharto held a meeting with several Catholic leaders, including Ignatius Joseph Kasimo and Frans Seda. Even before they were seated, Soeharto reportedly told the men, “Our common enemy is Islam.”

Soeharto was clearly determined to curb the power of Indonesia’s Islamists. In 1978, he created a directorate within the Ministry of Education to service traditional religions, including Kejawen, telling the Indonesian parliament, “These beliefs are part of our national tradition, and need not to be opposed to [established] religions.”

It was a clever move against the discriminatory regulations against religious minorities that were in place when Soeharto took power. Going back to January 1946, Indonesia had established the Ministry of Religious Affairs, a government body that facilitated discrimination against religious minorities and refused to recognize or serve the country’s traditional, local religions like Kejawen. The ministry produced a narrow definition of religions in 1952, favoring only monotheistic religions including Islam and Christianity, and drafted the 1965 blasphemy law, which has been repeatedly used with deleterious effects against followers of local religions.

Soeharto did not push the Ministry of Religious Affairs to serve local religions like Kejawen, but instead put the mandate under the Ministry of Education, changing its name to the Ministry of Education and Culture.

He supported his education minister, Daoed Joesoef, himself a devout Muslim, to issue a regulation on state school uniforms that banned the jilbab, the Indonesian name for the head, neck, and chest covering worn by women and girls to promote Islamic beliefs.

Significant tensions arose between Soeharto and the military in 1988 after a close aide, General Benny Moerdani, himself a Catholic, advised Soeharto to differentiate between his official duty and his children’s business interests, which were widely alleged to be connected to corruption. Soeharto recognized that maintaining his grip on power would require eliciting support from other, opposing groups, especially the Islamists.

So in 1991, Soeharto reversed his approach toward them. He made a pilgrimage to Mecca, promoted his Islamic credentials, embraced political Islam, and extended his support for the Indonesian Association of Muslim Intellectuals, where many Islamists channel their political aspirations. The Ministry of Education and Culture issued new guidelines on school uniforms that allowed “special clothing,” which gave birth to policies allowing state schools to allow their female teachers and students to wear the jilbab.

This was the beginning of the slippery slope towards greater introduction of the Islamization in Indonesia, all for the sake of Soeharto’s continued political power. But even that power was not to last.

In 1998, after more than three decades in power, Soeharto was forced to step down in the face of massive public protests at the height of the Asian economic crisis.

The reversal of Soeharto’s efforts to support religious freedom reopened the door to establishing Sharia, or Islamic law, which was previously frowned upon under his administration. This prompted Muslim politicians in predominantly Muslim provinces to draft ordinances that reflected “Islamic values.”

“What kind of Islam is this?”

When Soeharto’s wife, Siti Hartinah, died in April 1996, the Soehartos organized the funeral like a Kejawen family. Her body was placed inside a coffin – not wrapped in white muslin in accordance with Islamic rites. There was no imam reciting the Islamic confession of faith into the ear of the deceased.

Then-Vice President B.J. Habibie visited the house with his wife and two sons. At one stage, Habibie’s 32-year-old elder son, Ilham Akbar Habibie, remarked, just a little too loudly, “What kind of Islam is this?”

On things that mattered most, Soeharto revealed that spiritually he was really a Kejawen believer, in line with the teachings of Daryatmo, who had inspired him as a youth. But his use of his Islamic credentials to maintain power backfired on him – and on Indonesia.

President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who ruled between 2004 and 2014, accommodated the demands to promote Islamic Sharia. His administration strengthened the blasphemy law, leading to the prosecution and imprisonment of 125 people in a decade – a steep rise from only eight cases in the three decades during Soeharto’s rule.

The blasphemy law recognizes only six religions in Indonesia: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Under the Yudhoyono administration, the blasphemy law was also expanded to discriminate against smaller non-Sunni Islamic minorities, such as the Ahmadiyah and Shia sects.

The blasphemy law became a political weapon to mobilize Muslims against adherents of other religions. The prime example was the move to unseat Jakarta Governor Basuki Purnama, a Christian, who lost the 2017 local election after 500,000 Muslim protesters mobilized to demand that he should be prosecuted for defaming Islam in a public speech. Purnama also lost his freedom, ending up in prison for two years on bogus charges.

So Soeharto, a true Kejawen believer, who often visited Javanese shrines like Mount Srandil and Dieng Plateau, failed to use his perspective, knowledge, and power to promote religious freedom and belief in Indonesia. Indonesia is far worse off today because of the path Soeharto took to employ Islam to bolster his political power, and followers of local religions like Kejawen face a grave reckoning.

Mbah Salio nodded, repeatedly, when I wished for religious freedom and belief in Indonesia.

“That is also my prayer,” he whispered.