Summary

Over the past two decades, women and girls in Indonesia have faced unprecedented legal and social demands to wear clothing deemed Islamic as part of broader efforts to impose the rules of Sharia, or Islamic law, in many parts of the country. These pressures have increased substantially in recent years.

In 2014, the Indonesian government issued a national regulation on school dress that has been widely interpreted to require female Muslim students to wear a jilbab as part of their school uniform. Prior to and since this regulation, many provincial and local governments in Indonesia have adopted several hundred Sharia-inspired regulations, many of which are targeted at women and girls, including their dress. In Indonesia, the term “jilbab,” which literally means “partition” in Arabic, is widely used to refer to a cloth that covers a woman’s head, neck, and chest. Hijab, which means “cover” in Arabic, is typically a cloth that covers the hair, ears, and neck but sometimes also covers the chest. Many Muslim women and girls also wear long-sleeve shirts and long dresses.

This report focuses on the discriminatory regulations and related social pressures on women and girls to wear the jilbab or hijab in schools, within the civil service, and at government offices. Women, girls, and family members from around Indonesia described to Human Rights Watch the impact of discriminatory dress regulations in these and other spheres, from evening curfews to riding on motorcycles.[1]

A woman in Yogyakarta described the impact of the 2014 national student dress code on her teenage daughter, who went to state school in 2017: “Although the school and her teachers do not all explicitly say she must wear jilbab, they tend to give unsolicited comments or make fun of her choice not to wear jilbab. The pressure is in a way implicit, but constant.”

She said that her daughter was able to handle the situation in the first year, but in the second year she had an Islamic teacher for homeroom and the pressure to wear a jilbab became unbearable:

When he saw me, her teacher said, “Oh, I'm just following the school rules here.” “Can I see the rulebook?” I asked him. He then gave it to us. We went home and studied it. That is when I found out that although it doesn't say that female students have to wear jilbab, from the way they phrase it, it suggests that if a female student is Muslim, she must wear jilbab. That is what's implied.[2]

The jilbab rules also affect female civil servants in Indonesia. A lecturer at a public university in Jakarta who wishes to remain anonymous told Human Rights Watch that she was under pressure to wear a jilbab despite the absence of any campus regulation. She pointed to a huge billboard reminding all female visitors on campus to wear “Islamic attire.” She said it embodies attitudes she faced every day that made her uncomfortable, adding that the university only mandates “decent clothing” in its regulations. The constant pressures finally prompted her to resign in March 2020. She took a new job at a private university where she says she is not judged for teaching without a jilbab.

I receive comments asking why I do not cover my hair as I should as a Muslim. I got very traumatized from these incidents and felt discouraged [so I left my job].[3]

The Indonesian government’s compulsion or acquiescence to pressure women and girls to wear a jilbab is an assault on their basic rights to freedom of religion, expression, and privacy. And for many, it is part of a broader attack on gender equality and the ability of women and girls to exercise a range of rights, such as to obtain an education, a livelihood, and social benefits. The threat of being denied an education or job is a highly effective way of persuading a woman or girl to wear a jilbab, at considerable psychological cost.

Mandatory dress codes have even exposed women and girls to unnecessary physical dangers. Women in parts of the country who are forced or pressured to wear long hijabs and required to wear long skirts instead of long pants risks having their clothes getting caught in motorcycle wheels, particularly if also required to ride side-saddle, as they are in Aceh.[4] In February 2020, 10 Girl Scouts wearing long skirts died when they were swept into a river during a hike in Yogyakarta. The search and rescue team said that the long skirts had limited their physical movement and ability to avoid drowning.[5]

A woman in Cianjur who is required to wear a hijab and long skirt for her government job told Human Rights Watch: “I disagree with government interference on this hijab matter. I am afraid these measures will continue, with demands that [the hijab] becomes even longer and more restrictive. [I fear] they will add other rules that curb women, such as curfew restrictions.”[6]

Dahlia Madanih, who spent years monitoring local dress regulations for the governmental National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), said that once a local government begins to impose a mandatory jilbab, “other areas soon copy it, compelling either female civil servants or schoolchildren to wear the jilbab. The jilbab is seen as a symbol of female piety, high morality. Indonesia has a growing number of these mandatory jilbab areas, but they obviously do not correspond to piety and morality.”[7]

From Pancasila to “Islamic Sharia”

Indonesia’s founding president, Sukarno, and his successor, Suharto, saw a conservative interpretation of what was termed “Islamic Sharia” as a threat to the country’s guiding ideology of Pancasila, which established multi-culturalism as a foundation stone of the country’s political system.[8] However, in 1999, Suharto’s successor, President B.J. Habibie, under pressure to end a long and brutal civil armed conflict in Aceh, signed the Aceh Special Status Law, which for the first time in Indonesia’s post-independence history allowed part of the country to implement Sharia.[9]

While other parts of the country have no legal authority to impose Sharia, the law and subsequent agreements had the unintended consequence of emboldening religious conservatives. In 2001, three regencies in West Java and West Sumatra began requiring the jilbab in schools. Other regencies, mostly on Java, Sumatra, and Sulawesi islands, began to issue similar ordinances, making female teachers and students wear a jilbab.

As part of a larger decentralization effort, parliament in 1999 passed a regional autonomy law, amended in 2004, empowering provincial and local governments to regulate the education and civil service sectors. Some Islamic political parties and Muslim politicians, who came from “nationalist parties,” seized the opportunity to impose Sharia regulations and ordinances in various provinces and localities.

Although religion formally remains the domain of the national government and has not been decentralized, over the next decade, a plethora of religiously inspired discriminatory regulations and ordinances aimed at women were passed around the country often in the name of public order.

As of 2016, Komnas Perempuan had identified 421 ordinances passed between 2009-2016 that discriminate against women and religious minorities.[10] An academic study found that, by April 2019, more than 700 Sharia-inspired ordinances had been adopted.[11] Women and girls have been the most common target.

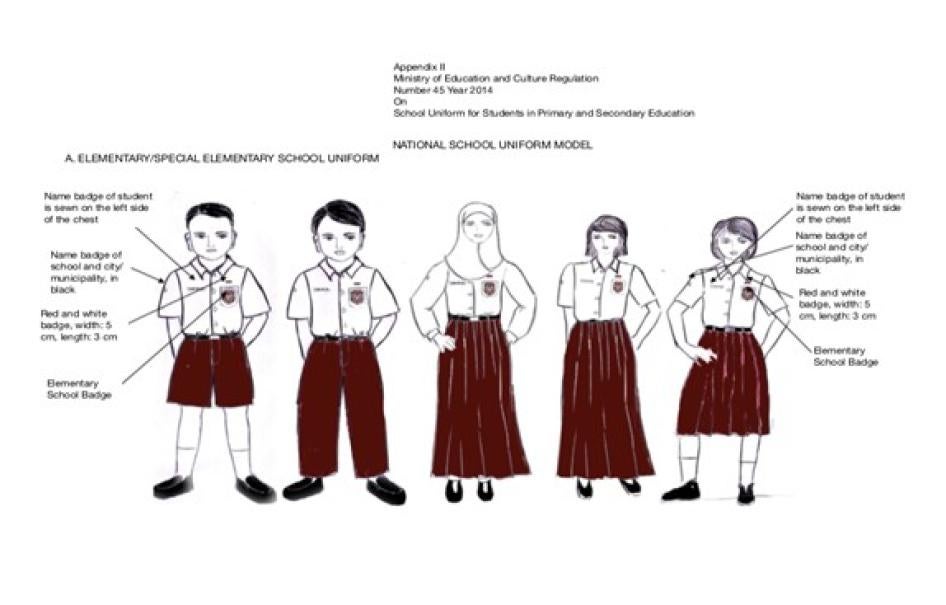

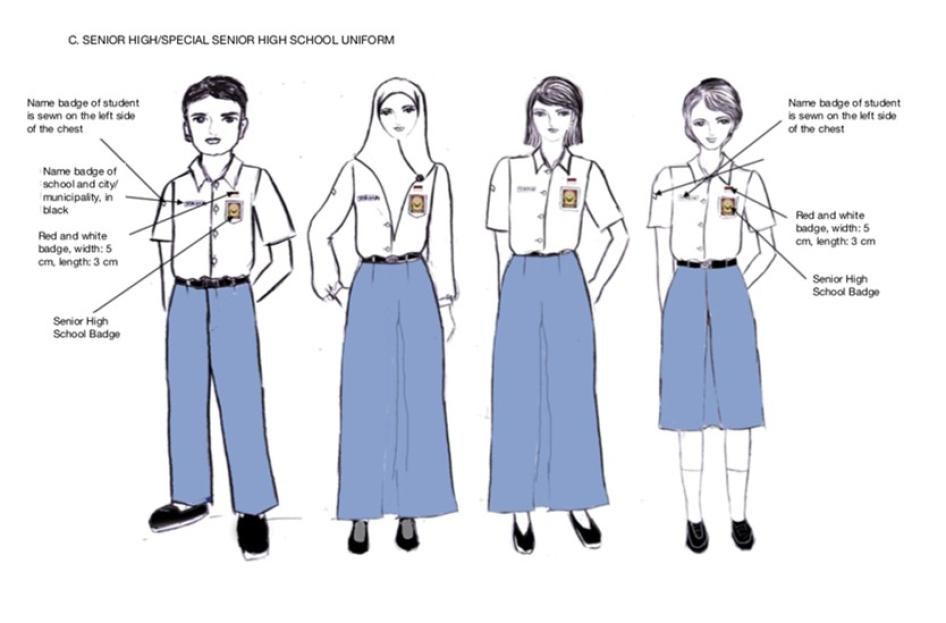

In June 2014, the government of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono opened the door even wider when Education and Culture Minister Mohammad Nuh issued a national regulation that, while ambiguously worded, implies and has been interpreted by officials and schools around the country to require all female Muslim primary and secondary school students to wear a jilbab as part of their school uniform.[12] While Sharia-inspired regulation of female dress in other domains remains limited to the provincial or local level, schools are now the subject of a de facto national policy.

The 2014 regulation grew out of dress requirements for Pramuka, the national scouting movement. The 2010 Pramuka Law compels all of Indonesia’s provinces, cities, and regencies to have Pramuka chapters as part of their extracurricular activities. While the law says that the Pramuka Movement is supervised by the Minister of Youth and Sports, in practice the Minister of Education and Culture plays a larger role as most Pramuka members are students. [13] The Pramuka Movement does not require school students to wear the official Pramuka uniform, but many local government leaders, who often also head Pramuka branches and supervise local education offices, make it mandatory for students to wear the scout uniform at least once a week. [14]

In December 2012, the chairman of the Pramuka Movement, Azrul Azwar, issued a 50-page instruction for “boy scouts and girl scouts.” This included a specific uniform for “female Muslims” that requires the jilbab, a long skirt or long pants, and a long-sleeve shirt. The official instruction includes pictures with details about the length and style of the clothes and headdress and specifies use of dark and light brown fabrics. [15]

In July 2014, Minister of Education and Culture Mohammad Nuh decreed that all schools, from primary to high schools, must include the Pramuka Movement as part of their extra-curricular activities and that all students should join. He also stated that all teachers should be accredited as “Pramuka mentors.” As a result, nearly all state school children, from grade 1 to grade 12, regularly wear the officially mandated Pramuka clothes to school at least once a week. [16] Regardless of whether girls choose to participate in extracurricular scouting activities, they are required to wear the uniform and, accordingly, jilbabs.

In a 2019 interview with Human Rights Watch, Nuh, now chairman of the Press Council, stressed that he did not include the word “mandatory” (wajib) in the 2014 regulation, explaining that it provides Muslim girls two uniform choices: a long sleeve shirt, long skirt and the jilbab, and the regular uniform without the jilbab. He said:

There is a genuine public aspiration to have these schoolgirls wearing jilbab. I do not object. I wrote that regulation. But it is not mandatory. I did not write the word “mandatory.” Any Muslim girl, any schoolgirl basically, from primary to high school, could choose, wearing jilbab or not.

If a Muslim schoolgirl chooses not to wear a jilbab—the jilbab uniform—it is not a problem. She could choose to do that. She should not face any sanction. It should be a free choice. I still see many Muslim girls not wearing jilbab. It is totally fine. If there’s a state school that makes it mandatory for a Muslim girl to wear jilbab, please report that school to the Ministry of Education and Culture. [17]

In practice, however, the 2014 regulation has been understood in many regencies and provinces as requiring a headscarf for all Muslim girls. In areas that have adopted this approach, a girl from a Muslim family who wished to be exempted from wearing the “Muslim girl” uniform would have to tell school authorities that she is not a Muslim, something girls from Muslim families are very unlikely to do – nearly all consider themselves Muslim even if they do not want to wear a jilbab.

This regulation prompted provincial and local education offices to introduce new rules, which in turn induced thousands of state schools, from primary to high schools, to rewrite their school uniform policies to require the jilbab for Muslim girls, especially in Muslim-majority areas. In such schools, Muslim girls are required to wear long-sleeve shirts and long skirts, along with a jilbab.[18]

Currently, most of Indonesia’s almost 300,000 public schools, particularly in the 24 predominantly Muslim provinces, require Muslim girls to wear the jilbab beginning in primary school.[19] Even where school officials have acknowledged to Human Rights Watch that the regulation does not legally require a jilbab, the existence of the regulation adds to the pressure on girls and their families to wear one.

Komnas Perempuan has repeatedly expressed concerns about discriminatory regulations, including those related to the jilbab. It has called on the national government, particularly the Ministry of Home Affairs, to revoke the local ordinances passed under the cover of the 2004 decentralization law and to end jilbab-related discrimination nationwide.[20] But the Yudhoyono government contended that the local ordinances (peraturan daerah) did not contradict national regulations as they represented “local values.”[21] His administration also allowed the adoption of elements of Sharia at the provincial and local level, including anti-Ahmadiyah and other regulations targeting religious minorities. [22] The subsequent Jokowi government has similarly failed to take action.[23]

Komnas Perempuan has identified 32 regencies and provinces with rules requiring the jilbab to be worn in state schools, the civil service, and in some public places, including Bengkulu, West Sumatra, and South Kalimantan provinces.[24] Some other predominantly Muslim provinces, such as Yogyakarta, have adopted similar regulations but have not made them mandatory, instead “calling on” or “advising” Muslim girls and women to wear the jilbab.

A 2019 report by the Jakarta-based Alvara Research Centre found that 75 percent of Muslim women in Indonesia, or approximately 80 million women and girls, were wearing the hijab.[25] It is unclear how many do so voluntarily and how many do so under legal, social, or familial pressure or compulsion.[26] Most wear one of three styles of Islamic headdress: kerudung (still showing hair), traditionally worn in many parts of Southeast Asia; jilbab (which in Indonesia refers to dress that covers the hair, ears, and neck), now the most common style in Indonesia; and the Saudi-style abaya (covering the whole body with a long robe). The abaya is sometimes combined with the niqab, a face veil showing only the eyes,[27] attire that is increasingly worn in Indonesia.[28] Its advocates say that the niqab (the term used in Indonesia to refer to the abaya or the abaya and the face veil) is “the perfect hijab” (kaffah jilbab) because it completely hides the shape of female bodies and their faces.[29]

Proponents have offered different justifications for the regulations, asserting they are necessary to cope with issues such as poverty, teen pregnancy, and pornography on the internet.[30] Currently, there is a campaign to pass a conservative Criminal Code that includes a provision that could be interpreted to authorize localities to apply hukum adat, or customary criminal law, aspects of which are blatantly discriminatory. [31] Many Muslim politicians argue that the jilbab is mandatory in Islam and that Muslim girls should be forced to wear the jilbab from a young age. Some criticize opposition to the mandate as “Islamophobia."[32]

Dewi Candraningrum, in her book Negotiating Women’s Veiling: Politics and Sexuality in Contemporary Indonesia, wrote that most veiled women do so in the name of Islam, “… compelled by parents and schools, as well as formal law.” She argued that schools are particularly influential, concluding based on surveys of girls and women in Java and Sumatra that school regulations were the most effective means of inducing girls to wear the jilbab.[33]

The Jokowi Administration’s Inconsistent Response

After Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, was elected president in 2014, hopes were raised among women’s rights advocates when the new home affairs minister, Tjahjo Kumolo, promised that he would review discriminatory regulations in the country. Meeting with leaders of religious minority groups in November 2014, Kumolo told them, “Indonesia is not a country based on any one religion. It is a country that is founded on the 1945 Constitution, which recognizes and protects all faiths.”[34] Pressed by Komnas Perempuan on jilbab regulations, the Home Affairs Ministry identified 139 ordinances that violate the rights of women and promised to look for ways to revoke them.[35]

This has not happened. While President Jokowi announced in June 2015 that his administration had scrapped 3,143 of 3,266 problematic local ordinances and bylaws because they contradicted higher regulations, promoted intolerance, or deterred investment, the main purpose was to invalidate local ordinances that hampered foreign investment. None of the jilbab or other Sharia-inspired ordinances were revoked.[36]

Following an attack by an Islamist couple on the chief security minister, Wiranto, in October 2019, the religious affairs minister, Fachrul Razi, suggested banning women civil servants from wearing niqabs at work. Facing public criticism from conservatives, Razi later apologized and stopped pursuing the ban.[37] However, the next month Razi and the newly appointed minister of education, Nadiem Makarim, signed a joint decree with other ministers to ban civil servants from using their social media accounts “to propagate hate speech and radicalism.” While the decree states that civil servants must be loyal to the state ideology of Pancasila, it did not directly mention Islamist radicalism or extremism, and did not address ordinances mandating the wearing of the jilbab.[38]

However, in November 2019 Jokowi’s newly appointed home affairs minister, Tito Karnavian, called on provincial and local officials nationwide to write ordinances based on Pancasila. He said they should not adopt any dress codes for civil servants that deviate from Pancasila.[39]

On January 11, 2021, Elianu Hia, a Christian father, recorded a meeting with a teacher in his daughter’s SMKN2 state school in Padang, during which the teacher pressured him to ask his daughter, herself a Christian, to wear a jilbab at school. He asked the teacher, “Is it advice or an order?” The teacher replied, “This is the school regulation at SMKN2 Padang. This is a mandatory jilbab rule.” After Elianu Hia uploaded the video and the school letter on Facebook, the story was reported by the media and national television, prompting netizen protests against the school and the education office in West Sumatra.[40]

On January 24, 2021, the Minister of Education, Nadiem Makarim, responded in a video statement, condemning the abuse at SMKN2 in Padang and saying that the "mandatory jilbab regulation" at the school, or any state school in Indonesia, is against the constitution, against the education law, and against the 2014 public uniform regulation. He told the Padang local government to order the school to change its policy. The school complied, but at the time of writing it had not formally changed the regulation. That week, five Christian female students attended their classes without a jilbab, quoting Makarim’s statement. However, other Christian girls continued to wear a jilbab, saying they were afraid to attend without one since the principal had not changed the regulation.[41] On February 3, 2021, Education and Culture Minister Nadiem Makarim, Home Affairs Minister Tito Karnavian, and Religious Affairs Minister Yaqut Cholil Qoumas signed a decree that allows any student or teacher to choose what to wear in school, with or without “religious attributes.” The decree orders local governments and school principals to abandon regulations requiring a jilbab in thousands of state schools around the country.[42] On February 10, the Indonesian Ulama Council sent a letter to the government asking for the school uniform regulation to be revised so that Muslim teachers are allowed to teach Muslim schoolgirls that it is “appropriate” for Muslim girls to wear the jilbab. The decree does not prohibit girls from wearing a jilbab. The letter criticized the decree for leading to “noisy protests.”[43]

The Need for Legal Reform

After the government revoked thousands of local ordinances to promote its business-friendly program, rumors and speculation circulated widely that the revoked regulations included Sharia-inspired regulations, including mandatory jilbab bylaws. Nahi Munkar, an Islamic blog, incorrectly headlined that the Jokowi administration had “revoked” Islamic-ordinances, listing some mandatory jilbab ordinances.[44] Kumolo immediately issued a statement that none of the 3,143 ordinances were Sharia-inspired and called on the public to ignore the rumors.[45]

The removal of the investment-related ordinances, however, infuriated the Indonesian Association of Regency Governments (Asosiasi Pemerintah Kabupaten Seluruh Indonesia, or Apkasi).[46] It filed a petition with the Constitutional Court seeking a ruling that the Ministry of Home Affairs lacked the authority to invalidate local ordinances. Apkasi asked the court to invalidate articles from the 2014 Regional Governance Law authorizing the Ministry of Home Affairs to revoke local ordinances.

The government defended its position, but in 2017, the Constitutional Court ruled that that Home Affairs Ministry's decision to cancel local regulations had violated the 1945 Constitution and that cancelling local regulations could only be done through a judicial review at the Supreme Court.[47] The commissioner of Komnas Perempuan, Khariroh Ali, explained the impact of the Constitutional Court decision: “By ending the central government’s authority to revoke bad regulations, the court ruling has let local governments off the leash.… These uncontrolled local regulations will be the source of discriminatory regulations against minorities.”

The government has thus far failed to bring a case at the Supreme Court challenging local regulations as discriminatory. While private actors can file a case, Supreme Court rules do not allow witnesses, experts, or other relevant parties to testify in court.[48]

Tim Lindsey, a legal expert on Indonesia at Melbourne University, described the situation as a “constitutional hole.” The Constitutional Court can only rule on the constitutionality of laws, not regulations. The Supreme Court only considers whether laws and regulations were properly adopted, not their constitutionality. This means there is no judicial venue to determine the constitutionality of a large number of regulations, including the jilbab rules. This is problematic because in Indonesia the real-world impact of laws is often found in implementing regulations, such as the jilbab regulations. Lindsey suggested that the Constitutional Court should reconsider its position in order to remedy this problem.[49]

If the Constitutional Court and Supreme Court continue to allow discriminatory regulations to be implemented, the national government will only be able to address them through superseding national legislation that expressly prohibits discriminatory dress and other provisions.

The contradictory signals from the Jokowi administration highlight how the fight over women’s rights and autonomy is one of the most important and contested issues in Indonesia, having a major impact on the country’s social, economic, and political future. Devi Asmarani, publisher of Magdalene, an online women’s magazine in Jakarta, captured the broader public resonance of the jilbab issue: “No other women’s rights stories, from rapes to #MeToo rallies, from celebrities’ profiles to our long features, can compete with jilbab stories. All stories about the pros and cons of jilbab are widely read on our website, often with the highest readership.”[50]

Requiring women and girls to wear a jilbab is part of a movement by conservative religious and political forces to reshape human rights protections in Indonesia. It undermines women’s right to be free “from discriminatory treatment based upon any grounds whatsoever” under Indonesia’s Constitution. Women are entitled to the same rights as men, including the right to wear what they choose. International human rights law guarantees the right to freely manifest one’s religious beliefs and the right to freedom of expression. Any limitations on these rights must be for a legitimate aim, applied in a non-arbitrary and non-discriminatory manner.

Key Recommendations

Human Rights Watch opposes both forced veiling and blanket bans on the wearing of religious dress as disproportionate and discriminatory interference with basic rights and has repeatedly criticized governments for excessive regulation of dress.

Human Rights Watch urges the Indonesian government to:

- Actively enforce the February 3, 2021, decree issued by the Ministries of Education and Culture, Home Affairs, and Religious Affairs that bans abusive, discriminatory dress codes for female students and teachers in Indonesia’s state schools.

- Issue a public policy statement that all national and local ordinances and regulations requiring the jilbab and other female clothing are discriminatory, should not be enforced, and should be repealed.

- Order government officials, including governors, mayors, regents, and other local officials, to revoke discriminatory ordinances and to stop pressuring women and girls to wear the jilbab or other religious dress. Take disciplinary action against local government heads and government employees who violate this order.

- Send to parliament draft legislation repealing existing provincial and local regulations that discriminate on the basis of gender, including regulations that require women and girls to wear a jilbab or other prescribed clothing, and banning any new discriminatory regulations in the future.

- Instruct the Pramuka (the national scouting movement) to repeal provisions of the 2012 scout uniform regulation that have been widely interpreted as requiring female scouts and schoolgirls to wear the jilbab and other religious dress at school and during their outdoor activities including the long skirts.

- Work with Islamic organizations, including the Nahdlatul Ulama and the Muhammadiyah, to create a public messaging campaign against requiring or pressuring women and girls to wear the jilbab or other Islamic dress, and promoting tolerance and inclusivity.

Glossary

|

Abdurrahman Wahid (1940-2009) |

A leading Muslim scholar, he was Indonesia’s fourth president (1999-2001). His grandfather was a founder of the Nahdlatul Ulama, the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia. Popularly known as “Gus Dur,” Wahid chaired the organization from 1984-1998. |

|

Ahmadiyah |

An Islamic revivalist movement, founded in Qadian, Punjab, originating with the teachings of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908). In Arabic, Ahmadiyah means “followers of Ahmad.” Its adherents are often called “Ahmadis.” It first appeared in Indonesia in Sumatra in 1925. It was legally registered in Jakarta in 1953. |

|

Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie (born 1932) |

Indonesia’s third president. A German-trained aeronautical engineer, he became President Suharto’s vice president in March 1998 and replaced him in May 1998. He lost a bid for reelection in 1999. |

|

Cadar |

Veil, from the Arabic word cador. In Indonesia, it covers the head, face, neck, and below the chest, showing only the eyes. |

|

Darul Islam |

Armed movement established in Garut, West Java, in 1949, to set up an Islamic state in Indonesia. In Arabic, Dar al-Islam means house or abode of Islam and is commonly used to refer to an Islamic state. |

|

Hidayah |

“Godly guidance” in Arabic. It is usually used to politely ask Muslim women to wear the hijab. |

|

Hijab |

From the Arabic term al hijab (الحجاب), meaning “cover.” It refers to a cloth that covers a woman’s head, neck, and chest that some Muslim women wear outside their homes or in the presence of any male outside of their family. |

|

Jilbab |

From the Arabic term al jalb (الجلب), meaning “partition.” It refers to a cloth that covers a woman’s head, neck, and chest. This term is more widely used in Indonesia than the term hijab. |

|

Joko Widodo (born 1961) |

Indonesia’s seventh president from 2014 to the present. Born in Solo, Central Java, from a commoner family. Before going into politics, he was in the furniture business. He is the only Indonesian president who did not come from the country’s political elite or a had military background. |

|

Kebaya |

A traditional blouse-dress combination that originated from Java Island and is traditionally worn by women in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. They are usually colorful embroideries. A kebaya is usually worn with a jarit or unsewn batik. |

|

Kerudung or tudung |

A piece of fabric covering a woman’s head but still showing her hair. |

|

Komnas Perempuan |

National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komisi National Anti Kekerasan terhadap Perempuan), an independent state institution set up in 1999 under President B.J. Habibie. |

|

Muhammadiyah |

A Sunni Muslim reformist organization established in 1912 in Yogyakarta, Central Java. One of the largest mass organizations in Indonesia, it operates hundreds of hospitals and schools throughout Indonesia. In Arabic, Muhammadiyah means “followers of Muhammad.” |

|

MUI |

Indonesian Ulama Council (Majelis Ulama Indonesia), a semi-official Muslim clerical body founded in Jakarta in 1975 comprising Sunni Muslim groups, including Nahdlatul Ulama, Muhammadiyah, and smaller groups. |

|

Nahdlatul Ulama |

A traditionalist Sunni Islam organization established in 1926 in Jombang, East Java. It claims to have approximately 60 million members, making it the largest Muslim social organization in the world. It has more than 20,000 Islamic boarding schools, called pesantren, mostly in Java. |

|

Niqab |

From the Arabic term al niqab (نقاب), meaning “veil,” sometimes in Indonesia called kaffah hijab (perfect hijab). |

|

Pancasila |

Indonesian state principle or philosophy (literally, “five principles”) articulated at independence in 1945 consisting of five “inseparable” principles: belief in the One and Only God (thereby legitimizing several world religions and not just Islam); a just and civilized humanity; the unity of Indonesia; democracy; and social justice. It became the state ideology under President Suharto, under whom the promotion of alternative ideologies was considered subversion. It continues to be a key reference point in discussions of religion and religious pluralism in Indonesia today. |

|

PKS |

Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera) is an Islamist political party in Indonesia modeled on the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. |

|

Qanun |

Literally “law,” a term derived from Arabic (in English, “canon”), used in Aceh to refer to all ordinances enacted by provincial and regency administrations in the name of Sharia. |

|

Regencies, Cities |

Indonesia’s 34 provinces are divided into 514 regencies and cities. Regencies are mostly in rural areas. Cities are urban areas. |

|

Sharia |

Islamic law, or the body of legal regulations (fiqh in Arabic) elaborated by Muslim jurists. It is seen by many Muslims as a complete system of guidelines and rules which encompass criminal law (qanun jinayah), personal status law, and many other aspects of religious, cultural, and social life. There are many different schools of thought and different interpretations of the provisions of Sharia. |

|

Shia Islam |

The second largest denomination of Islam. In Arabic, Shia is the short form of the phrase Shīʻatu ʻAlī, meaning “followers of Ali,” a reference to Ali ibn Abi Talib (656–661), the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammad. Shia believe that Ali was the legitimate successor to Mohammad. |

|

Suharto (1921–2008) |

Indonesia’s second president (1966-1998). |

|

Sukarno (1901–1970) |

Indonesia’s first president (1945-1968). He adopted Pancasila as the state ideology, but also signed the blasphemy law in 1965. |

|

Sunni Islam |

The largest branch of Islam. In Arabic it is known as Ahl ūs-Sunnah wa āl-Jamāʿah or “people of the tradition of Mohammad and the consensus of the Ummah.” Sunni members believe that Mohammad’s successors were successively four caliphs: Abu Bakr, Umar al-Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan, and Ali ibn AbiTalib. Most Indonesian Muslims are Sunni. |

|

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (born 1949) |

Indonesia’s sixth president (2004-2014). |

|

Wahhabism |

An orthodox Islamic creed centered in and emanating from Saudi Arabia. It is named for preacher Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792), who formed an alliance with the House of Saud. |

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report from 2014 to January 2021, including 142 in-depth interviews with schoolgirls, their parents or guardians, female civil servants, educators, government officials, and women’s rights activists. Interviews took place on Java Island, including in the cities of Bandung, Banyuwangi, Boyolali, Cianjur, Cibinong, Cirebon, the Greater Jakarta area, Parapat, Rangkasbitung, Serang, Sukabumi, Surakarta, and Yogyakarta; on Sumatra Island, including in Banda Aceh, Bandar Lampung, Medan, Padang, Pekanbaru, Solok, and Sijunjung; on Kalimantan Island, including in Penajam Paser Utara, Pontianak, and Banjarmasin; on Sulawesi Island, including in Makassar, Maros, and Gorontalo; on Lombok Island in Praya; and Denpasar on Bali.

We conducted interviews with students and their family members in safe locations, sometimes close to schools or government offices. For security reasons, including interviewees’ fear of retaliation including bullying or intimidation, we have withheld the names of nearly all of the students forced to wear a jilbab even if they are now adults, and, in the case of those who are still children, we also withheld the names of their parents. Where we identify a person’s age, city, or organization, we do so with their consent. We have used real names only when the individual insisted that we use their names, and only then when we believed it was safe to do so. In most cases the people we name have previously been identified in media reports or written about their experiences themselves in blogs or social media.

Interviews with female students or former students were conducted one-on-one in English and Bahasa Indonesia by a female interviewer. We informed interviewees how the information gathered would be used and told them they could decline the interview or terminate it at any point. We also explained there would be no compensation for participation.

Our accounts of specific bullying or intimidation are based on interviews with students and teachers about the specific incident or, where indicated, on secondary media sources that we cross-checked with witnesses with direct knowledge of or involvement in the incidents. In addition, we reviewed an incident in a public high school in Bandar Lampung that was recorded on a mobile phone. The victim shared her 19-minute ordeal inside the school’s counselling room. Another source in Bandung gave us a 30-page letter that she wrote to her mother about jilbab bullying she had experienced. A high school student in Solok, a city near Padang, gave us her school regulation book which sets forth the points system used for punishing students who do not wear the jilbab or wear it incorrectly.[51]

I. Women’s Rights and Sharia from the Dutch Indies Period through the Suharto Regime

On December 22, 1928, about 1,000 people attended the Dutch Indies’ first women’s congress in the city of Yogyakarta, on Java, with 15 speakers representing various organizations. The attendants were mostly Dutch-educated teachers, writing and presenting their speeches in the Malay language (now Bahasa Indonesia). They discussed various issues during the four-day conference: regulations on marriage and divorce, girls’ education, child marriage, female laborers, and the women’s rights movement in Europe. Polygamy and child marriage, issues related to Sharia, attracted huge debate when secularists and Muslim activist participants advocated divergent views.[52] The strong influence of the wave of nationalism meant that the underlying spirit of the congress was “countering or managing the existing diverse ideologies and interests with the primary purpose of attaining liberty from Dutch colonialism.”[53]

Debates about women’s rights and “Islamic Sharia” continued in the coming decades. Three more women congresses were held in 1935, 1938, and 1941. Women with diverse Islamic views debated polygamy, child marriage, and the mortality rate of young children—but they never mentioned the hijab.[54] Susan Blackburn, an Australian scholar who focuses on women’s rights in Indonesia, contends that during the Dutch colonial period it was easier to smooth over the contradictions within the Islamic world by reference to shared nationalist goals. All anti-colonial activists wanted to be independent, supported nurturing Bahasa Indonesia as the national language, and worked to strengthen civil society groups.[55]

The divide between radical and moderate Islamic views, including on women’s attire, however, became more difficult to bridge after Indonesia’s independence in 1945.[56] Indonesia’s founding president, Sukarno, who led the country from 1945 to 1965, faced increasing pressures from Islamists. In 1965, he passed a blasphemy law, which an accompanying presidential decree conferred official recognition on only six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. The Islamists did not advocate to make the hijab mandatory; no law or regulation required women and girls to wear the hijab.[57]

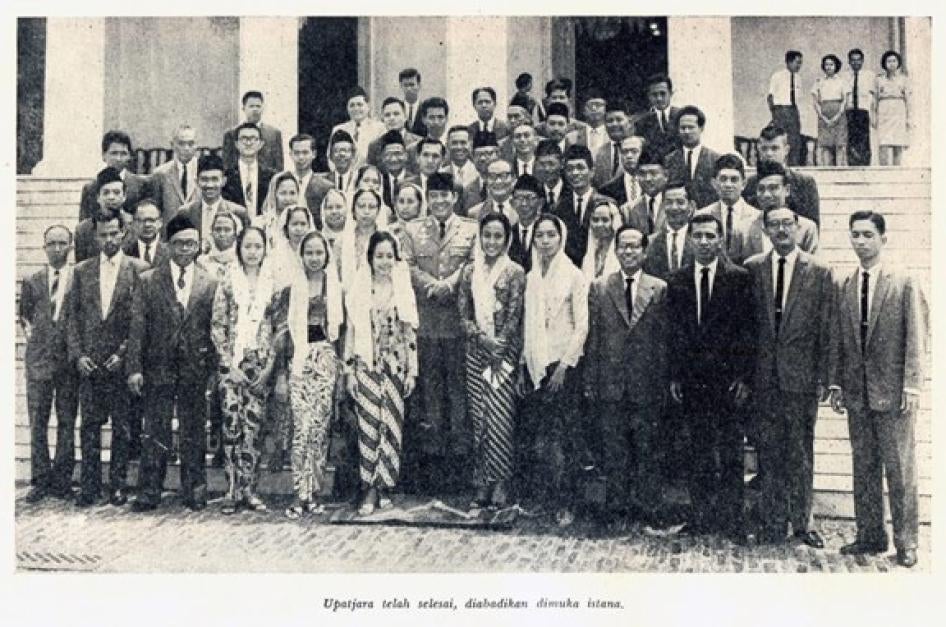

A 1965 photo of Muhammadiyah leaders shows them posing with Sukarno at the State Palace in Jakarta. At the time, Muhammadiyah already had long been Indonesia’s second largest Muslim group and Sukarno had been a member since he was a young man. These Muslim leaders presented Sukarno with the Muhammadiyah Star, an award to recognize Sukarno’s contribution to the development of the organization. The visitors included 12 top Muhammadiyah female leaders. They all wore a traditional Javanese outfit made up of an unsewn long batik sarong or jarit around the waist, a colorful kebaya blouse, and a white kerudung headscarf partly showing their hair.[58] It was typical Javanese women’s attire.

Alissa Wahid, a Nahdlatul Ulama activist, said that her mother and grandmother, themselves ulamas, also wore kebaya, jarit, and kerudung, and regularly taught the Quran. The Nahdlatul Ulama is the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia. Wahid is the eldest daughter of former president Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid and Sinta Nuriyah:

My own grandmother [Solichah], Gus Dur’s mother, wore a hijab that is not worn by most Muslim women in Indonesia today. She was wearing [something similar to] what I wear. I am wearing this kerudung as a tribute to my grandmother. Solichah is the daughter of a great ulama and the daughter-in-law of another great ulama. Her husband is also a great ulama. Her son, Gus Dur, is my father, also a great ulama. Hijab has historically multiple interpretations. I am worried about today’s single interpretation.[59]

Suharto and the Sidelining of Islamists

On September 30, 1965, a failed coup against President Sukarno claimed the lives of six army generals. The events surrounding the coup attempt remain unclear and some participants themselves described it as an internal military affair, but General Suharto soon took power and his government maintained that the Indonesian Communist Party was exclusively responsible for the coup attempt. From 1965 to 1967, the military and vigilantes carried out a bloodbath against leftists and suspected sympathizers, including many left-leaning feminists, in Java, Bali, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and other parts of Indonesia. Estimates of the number of people killed range from several hundred thousand to three million.[60]

Throughout his three decades in power, Suharto used Pancasila, the Indonesian state philosophy established in 1945, to control the country, including organizations considered to be supporters of “political Islam.” He rejected the idea to revive Masyumi, an Islamist party banned during the Sukarno period, and pressured all Muslim parties to make Pancasila their platform instead of Islam.[61]

On March 17, 1982, the Ministry of Education under Daoed Joesoef issued a decree on student uniforms in state schools. It was the first time in Indonesia that the government regulated school uniforms nationwide. It created three categories: red and white for primary school students (grades one to six); blue and white for junior high school students (grades seven to nine); and gray and white for senior high school students (grades 10 to 12). The categories were based on Indonesia’s existing school system. The decree removed the autonomy of state schools to regulate their own uniforms. It also implicitly banned schoolgirls from wearing the hijab as it did not include any type of headscarf as a choice for girls’ uniforms in any of the categories.[62]

Siyohelpiyanti, a school supervisor, told Human Right Watch that when she was in high school in Jakarta in the 1980s her friend was prohibited from wearing the hijab. “Her teacher forced students to take off their hijabs,” she said.[63] Some schools expelled students who wore the headscarf.[64]

The 1982 regulation came into effect three years after the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran as well as the 1979 seizure of the Great Mosque of Mecca, Islam’s holiest site, which helped trigger the rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia and fueled debates over the “politics of piety” in the Muslim world, including the place of female Muslim attire. In Indonesia, the increasing number of Muslim clerics who studied in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East advocated for a dress code for women based on Arabian norms, as well as other conservative restrictions on women imposed in the Gulf region. [65]

Muslim activists opposed the school uniform regulation over its implicit ban of the hijab and used it as a rallying point for protests against Suharto’s military-backed regime. Some students who wore the hijab were questioned in different locations in Java and Sumatra and cited two Quranic verses that they interpreted as requiring Muslim girls and women to wear it.[66] Some commentators suggest that the regulation helped unite previously diffuse Muslim ethnic groups.[67]

In 1991, Suharto reversed his approach to religion and politics. He made a pilgrimage to Mecca, flaunted his Islamic credentials, embraced political Islam, and extended his support for the Indonesian Association of Muslim Intellectuals, where many Islamists were to channel their political aspirations.[68] On February 16, 1991, the Ministry of Education issued a guideline on school uniforms that allowed “special clothing” (pakaian khas), but did not use the term “jilbab” or “hijab” as some Muslim organizations had sought.[69]

After more than three decades in power, in 1998 Suharto was forced to step down after massive public protests at the height of the Asian economic crisis. This opened an era of greater freedom in Indonesia that has since included regular and largely free and fair elections for parliament and the presidency.

Viewpoints long repressed emerged into the open. Many ethnic and religious groups promptly tried to create a new social reality, demanding more say in political, economic, and cultural domains. Some became involved in deadly conflicts, including in the province of Aceh, where the Free Aceh Movement had been fighting for independence since the 1970s. A strong thread of Islamist militancy emerged in different parts of the country. At least 90,000 people were killed in mostly communal violence in the decade after Suharto’s departure from office.[70]

II. Rise of Political Islam and Sharia-Inspired Regulations Since Suharto

The Aceh Precedent

In an attempt to end a longstanding separatist movement and armed conflict in the province of Aceh, the Indonesian parliament in 1999 granted “Special Status” and broad autonomy to Aceh, including allowing it to adopt ordinances derived from Sharia, the only province given authority to do so.[71] In 2002, the Aceh parliament passed a bylaw on “the belief, ritual, and promoting Islam,” which contains a mandatory jilbab regulation along with other Sharia-inspired provisions, such as making sex between unmarried adults and khalwat (a man and a woman together in private) crimes. In 2003, Aceh set up its own Sharia court and Sharia police (wilayatul hisbah). [72] In 2004, the Aceh parliament passed the Islamic Criminal Code (Qanun Jinayah).[73]

The Special Status agreement had the unintended consequence of emboldening religious conservatives elsewhere in Indonesia. In 2001, Indramayu regency in West Java issued a decree on “mandatory Islamic dress code and the Quran literacy for school students,” thereby becoming the first local government other than Aceh to issue a mandatory jilbab regulation.[74] Banten province soon followed, issuing its own ordinance.[75] In South Sulawesi province, six of the 24 regencies declared implementation of Sharia, including Bulukumba, Enrekang, Gowa, Maros, Takalar, and Sinjai.[76] West Sumatra and Riau provinces also passed Sharia-derived regulations. In East Java, Pamekasan regency on Madura Island declared a Sharia regulation, mandating that Muslim women and girls wear the jilbab in public.[77]

On October 14, 2002, Aceh Governor Abdullah Puteh signed a qanun (ordinance) on aspects of “belief, ritual, and promotion of Islam” that required all Muslims in the province to wear Islamic attire. This was defined as clothing that covers the aurat for men, the area of the body from the knee to navel. For women, it required covering the entire body except for the hands, feet, and face. The ordinance specified that “Islamic clothing” (busana Islami) must not be transparent or reveal the shape of the body.[78] Human Rights Watch has previously documented that some of those suspected of violating the ordinance have been violently assaulted or had their homes broken into by vigilante groups, who have largely acted with impunity.[79]

Aceh immediately became the exemplar for conservative political leaders elsewhere in Indonesia who supported the adoption of new Islamic ordinances, including mandatory jilbab regulations, to demonstrate their piety and gain political support.

Discriminatory Regulations Begin to Spread

Local governments began to issue new jilbab rules during the presidency of Megawati Sukarnoputri. On Java, Indonesia’s most populous island, the first jilbab ordinances were announced in some regencies in West Java province in 2001. One of the first areas in Sumatra other than Aceh to issue a mandatory jilbab regulation was Solok regency in West Sumatra province. Also, in 2001, Zainal Bakar of West Sumatra was the first governor to issue a mandatory jilbab decree for all female civil servants.[80]

On March 11, 2002, Solok Regent Gamawan Fauzi issued a 15-article regulation on Muslim attire aimed at schoolgirls and civil servants. It mandates girls and women to wear the jilbab. The regulation states that it only applies to Muslims and specifies sanctions and disciplinary action against Muslim women who do not comply.[81] Other regencies in West Sumatra, such as Pesisir Selatan, Tanah Datar, Sijunjung, Pasaman, and Agam, issued similar regulations.

In June 2004, Maman Sulaiman, the regent of Sukabumi, the biggest regency on Java, issued a local ordinance requiring the jilbab for female Muslim students. It not only called for Muslim schoolgirls to wear jilbabs, both in public and private schools, but also required the hijab for kindergarten pupils. It also warned “non-Muslim schools” —a reference to private Catholic schools—not to prevent Muslim girls from following this requirement.[82]

Proliferation of Jilbab Regulations During Yudhoyono Administration

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was elected president and then sworn into office in October 2004. He was reelected in 2009 and served until 2014. During his two terms in office, jilbab regulations spread throughout much of Indonesia, particularly in populous areas in Java, Sumatra, and Sulawesi.[83]

Yudhoyono’s administration repeatedly turned a blind eye to violence, threats, and intimidation by Islamist militants against religious minorities such as Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, traditional faith practitioners, and Shia, Ahmaddiyah, and other non-Sunni Muslims.[84]

In March 2005, Mayor Fauzi Bahar of Padang, the capital of West Sumatra, issued a decree on Muslim attire entitled, “Implementing the Requirement that Teenagers Recite the Quran in the Morning, Anti-Lottery/Drugs, and Islamic Attire for Muslim/Muslimah Students at Primary Schools, Junior High Schools, and Senior High Schools in Padang.” Article 10 of the decree states that, “Muslim students at primary schools, Islamic madrasah, junior high schools, and senior high schools must wear Muslim/Muslimah attire; non-Muslims should adopt [long skirts for girls and long pants for boys].” [85]

On its face the decree appears to be gender neutral. However, as schoolboys already wore long pants to school, only girls were affected. Muslim girls were now required to wear the jilbab, a long-sleeve shirt, and a long skirt, and non-Muslim girls were required to wear a long skirt. On March 30, 2005, the Ministry of Education in Padang sent a circular to all public and private schools attaching Mayor Bahar’s decree and instructing all principals to implement the jilbab rule for Muslim girls.[86]

In August 2005, Gamawan Fauzi, the governor of West Sumatra, issued a circular calling on all Muslims to wear Islamic attire; this included women and girls in all public spaces.[87] Fauzi would play a key role in regulating women’s and girls’ clothing. In 2009, Yudhoyono promoted him to be the home affairs minister. Fauzi promoted the adoption of Sharia provisions in predominantly Muslim provinces throughout Indonesia.

Also, in 2005, South Kalimantan Governor Rudy Ariffin issued a decree requiring women civil servants to wear a hijab and long skirt.[88] On December 30, 2005, Nadjamuddin Aminullah, the regent of Maros, South Sulawesi, signed a local ordinance on Muslim attire stating that sanctions would be enforced against Muslim civil servants and students who did not wear the jilbab.[89] As in Sumatra, this local ordinance spread to nearby areas. Five other South Sulawesi regencies—Bulukumba, Enrekang, Gowa, Takalar, and Sinjai— followed suit and passed local ordinances. In time, it spread further to regencies in other provinces in Sulawesi, such as Gorontalo.

2014 National Regulation on State School Uniforms

The Indonesian state school uniform regulation started with the case of a Muslim schoolgirl prohibited from covering her head at school.[90]

In January 2014, SMAN2 Denpasar public high school in Hindu-majority Bali and the Ministry of Education received a complaint after a Muslim student, Anita Wardhani, was not allowed to wear her hijab. The school argued that it was enforcing a school uniform rule that applied equally to all students and did not allow any head covering.[91] The controversy died down without much media coverage after the school allowed Wardhani to wear her hijab.

School principal Ida Bagus Sweta Manuaba told Human Rights Watch that Wardhani was already in her last semester, euphemistically saying, “We did not ban her hijab but asked her to delay wearing it [until her graduation].” The ban prompted the Ministry of Education to summon school officials to Jakarta. Manuaba said the authorities ordered the school to change its policy. “Now you see Muslim students in this school wearing hijab,” he said.[92]

Five months later, on June 9, 2014, the education and culture minister, Mohammad Nuh, a member of President Yudhoyono’s cabinet, issued a school-uniform regulation, including a provision outlining requirements for school uniforms that include the jilbab for Muslim girls.

The 2014 regulation specifies a national uniform and a variation for Muslim girls. There is no reference to any other religions or other group identities that might warrant a variation on the otherwise standard school uniform.

Illustrations in appendices, which are part of the regulation, show two options for boys, one with long pants and one with shorts. For girls, the illustrations show long-skirt and regular-length-skirt options, but include a third illustration, the “Muslim girl” (Muslimah) uniform, which is the long-skirt and long-sleeve shirt option with the addition of a jilbab. The regulation applies to all state schools in the country, and individual schools are not allowed to adopt different uniforms or abolish them altogether.[93]

The regulation includes broad language acknowledging freedom of religion (e.g., “school uniforms are to be dealt with [diatur] by each school with consistent attention to the rights of each citizen to follow their own religion,”) and even the definition of the Muslim girl uniform refers to the “personal beliefs” of the girl (“The Muslim girl uniform is a uniform worn by Muslim girls because of their personal religious beliefs [karena keyakinan pribadinya] …”).

In a 2019 interview with Human Rights Watch, Mohammad Nuh, the minister who signed the regulation, and now the chairman of the Press Council, stressed that he did not include the word “mandatory” (wajib) in the regulation, explaining that the regulation provides two uniform choices: a long sleeve shirt, long skirt and the jilbab, and the regular uniform without the jilbab. He said:

There’s a genuine public aspiration to have these schoolgirls wearing jilbab. I do not object. I wrote that regulation. But it’s not mandatory. I did not write the word “mandatory.” Any Muslim girl, any schoolgirl basically, from primary to high school, could choose, wearing jilbab or not. If a Muslim schoolgirl chooses not to wear a jilbab—the jilbab uniform—it’s not a problem. She could choose to do that. She should not face any sanction. It should be a free choice. I still see many Muslim girls not wearing jilbab. It’s totally fine. If there’s a state school that makes it mandatory for a Muslim girl to wear jilbab, please report that school to the Ministry of Education and Culture.[94]

In practice, however, the 2014 regulation has been understood in many regencies and provinces as requiring a headscarf for all Muslim girls. In areas that have adopted this approach, a girl from a Muslim family who wished to be exempted from wearing the “Muslim girl” uniform would have to tell school authorities that she is not a Muslim, something girls from Muslim families are very unlikely to do—nearly all consider themselves Muslim even if they do not want to wear a jilbab.

This regulation prompted provincial and local education offices to introduce new rules, which in turn promoted thousands of state schools, from primary to high schools, to rewrite their school uniform policies to require the jilbab for Muslim girls, especially in Muslim-majority areas. In such schools, Muslim girls are required to wear a jilbab as well as long-sleeve shirts and long skirts.[95]

III. Jilbab in Schools

The teachers use scissors. They cut the female students’ clothes if the shirts were considered not meeting the school regulation, too tight or too short. Then the students get this mark on their disciplinary book. They lost some points. No students dare not to wear the jilbab to go to school. A classmate got expelled from the school when she was protesting a teacher telling her to wear a jilbab.

–16-year-old student at public high school in Solok, West Sumatra, August 2019

Indonesia has more than 297,000 state schools (sekolah negeri). They are divided into five educational categories: approximately 85,000 kindergartens; 147,000 primary schools; 37,000 junior high schools; 12,000 senior high schools; and 12,000 technical high schools.[96] Indonesia’s Ministry of Religious Affairs also administers its own Islamic public schools—from elementary to senior high school—exclusively for Muslim students.

The Ministry of Education and Culture in Jakarta oversees state schools around the country through complex arrangements with local governments. Indonesia’s universities are mostly private institutions, although the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Religious Affairs jointly administer 550 state universities.[97]

It is not clear how many state schools, especially in Indonesia’s 24 predominantly Muslim provinces, have compulsory hijab regulations for their Muslim students. The number of localities and schools requiring the hijab is growing, as are the number requiring clothing that covers more and more of girls’ hair and bodies.

In schools in some conservative areas, it is not only Muslim girls who are required to wear hijabs. Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of non-Muslim girls, mostly Christians, who said that they were forced to wear the jilbab uniform even though they did not want to wear it on faith grounds.[98]

These hijab regulations violate Indonesia’s obligations under international human rights law to protect the rights to freedom of religion and expression, the rights to privacy and personal autonomy, the best interests of the child, and the right to education, as in many cases schoolgirls are pressured not only to wear clothing, they dislike but also to leave their schools, temporarily or permanently, if they fail to comply. Those who were not forced to leave still described harm to their education, including bullying, humiliation, and lower grades for not wearing hijab.

Pressure and Bullying in Schools

Indonesian state schools use a combination of psychological pressure, public humiliation, and sanctions to persuade girls to wear the hijab. This environment encourages peer pressure and bullying by teachers and fellow students to ensure that “good Muslim girls” wear a hijab. Human Rights Watch found instances in which school officials dropped the jilbab requirement following a parent’s complaint to the government. But for the most part, state schools are, at best, failing to protect girls from harassment and bullying that interferes with their education and, at worst, encouraging and perpetrating them.

Nadya Karima Melati, now a 24-year-old activist, spoke about the three difficult years she had to endure facing bullying and pressure from teachers to wear the jilbab after she enrolled at SMAN2 senior high school in Cibinong, Bogor regency, near Jakarta. She came from a private middle school where girls did not wear jilbabs or long skirts and so, before she enrolled at the public high school, she spoke to teachers there about school uniforms. She was told that the school had two options for girls, one with the jilbab and one without, and she could choose the latter option. When she went to buy her uniform at the school, however, she found there was only one option. As she put it: “I felt like I was being cheated. All new students wore jilbab. In fact, all female students in this school wore jilbabs. It was mandatory.”[99]

In her first year, Melati wore a jilbab when entering the school compound but took it off inside the classroom. She said that the teachers did not accept this and “advised” her to wear a jilbab inside the classroom. She reluctantly followed the request. In her second year, Melati said she rebelled by taking off her jilbab after she walked out the school gates.

Melati’s high school has a chapter of the Rohani Islam (Islamic Spiritual Guidance), an extracurricular Islamic prayer network established in many high schools in Indonesia, associated with the Indonesia affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood. Whether or not a Muslim girl wears the jilbab is one of the first ways the Rohani Islam measures their piety.[100]

Rohani Islam began in the late 1970s in West Java, gradually setting up branches in many schools throughout Java and Sumatra. It usually operates under the guidance of the Islamic class teacher in each school.[101] Analysts describe it as the driving force to radicalize high school students in Indonesia.[102]

Melati said she faced serious peer pressure from this group, whose members often criticized her for not always wearing the jilbab. The school’s Islamic teacher, who even opposed the teaching of singing in the school, was the dominant voice within this network.[103]

Melati said that her struggle with the jilbab also took place at home. Melati’s mother, herself an Islamist activist who had struggled against President Suharto’s ban on the hijab in the 1990s, used the school’s rigid approach on hijabs to pressure Melati to wear her hijab full-time in public spaces. She said she could only take her hijab off at home: “My mother does not understand that wearing or not wearing a jilbab should be an individual choice. The high school rule gave my mother another chance to pressure me to wear a jilbab, creating disputes between us for years.”[104]

A former student at SMAN1 Solok high school said she was punished in 2012 for having a hair-bun under her jilbab. Hair-buns are considered to be fashionable and immodest by some conservatives and were banned in that school. She was humiliated by being forced by her teacher to wear a motorcycle helmet in the classroom over her jilbab.[105]

Tempo magazine reported that two state high schools in Yogyakarta, SMPN7 and SMPN11, had compelled Muslim girl students to wear long-sleeve shirts, long skirts, and the jilbab. The principal of one of the schools had even put the requirement in writing in a July 13, 2017 circular. Several parents protested, making statements to the media and demanding that the Ministry of Education inspect the schools. The school principal denied that wearing a jilbab was required despite his written circular. Instead, he said it was only “advice” and that “no sanction” was imposed on students who refused to wear it, though he added that “good Muslim girls” should wear the jilbab.[106]

Another woman in Yogyakarta, whose teenage daughter went to SMPN8 public school in 2017, explained how the jilbab issue had played out at her daughter’s school, where the school dress code is based on the 2014 national regulation:

Although the school and her teachers do not all explicitly say she must wear jilbab, they tend to give unsolicited comments or make fun of her choice not to wear jilbab. The pressure is in a way implicit, but constant. My daughter was able to put up with it during the first year, but into the second year, her homeroom teacher was again a religious [Islamic] teacher. Then it only got more explicit.

When he saw me, her teacher said, “Oh, I'm just following the school rules here.” “Can I see the rulebook?” I asked him. He then gave it to us. We went home and studied it. That is when I found out that although it doesn't say that female students have to wear a jilbab, from the way they phrase it, it suggests that if a female student is Muslim, she must wear hijab. That is what's implied.[107]

She reported SMPN8 junior high school in Yogyakarta to the National Ombudsman Office because the school principal, the Islam religion teachers, and other students had routinely bullied her daughter into wearing a jilbab since she entered the school:

Whenever it's religion class, and whenever her (Islamic) teacher runs into her, he would ask why she's not in jilbab. He would even ask, “Will you wear it tomorrow?”

My daughter would just say “Yes, okay.” But as soon as she comes home, she shares with me her discomfort, “Why are they like that, Mom?”

I realized that the school has been pressuring students to wear jilbab even though the principal denies it. On my first visit during the first year, as well as at every parent-teacher meeting, she would say, “No, it’s not mandatory.” But on another visit with her [in the second year] the principal didn't exactly say no. She implied that I should just get on with it. “What's so hard about that?” she said.[108]

This teenager has since finished her three years at SMPN 8 but still faces bullying for refusing to wear a jilbab. Her mother and father, themselves Sunni Muslims, continued defending the rights of their daughter. Sometimes the girl wears the jilbab during Islamic class and prayers, but most of the time she refuses to wear it.

The National Ombudsman Office visited the school and found in February 2019 that the school regulation does not explicitly mandate the jilbab for Muslim girls but creates pressure on the girls, noting that the principal and Islamic teachers have “pressured” Muslim girls to wear jilbab. The ombudsman asked the school to correct the regulation.[109] However, some other parents, who supported the jilbab rule, asked the school to expel the protesting girls. The mother said, “My daughter finally compromised. She sometimes uses her jilbab. She sometimes also does not use it, depending on the situation. If the situation is hostile, she will use her jilbab.”[110]

In January 2020 in Sragen, Central Java, a father reported his daughter’s SMAN1 Gemolong school to the police and the local government after his daughter was bullied for not wearing a jilbab. Agung Purnomo said that members of the school’s Rohani Islam group had “systematically pressured and intimidated” his daughter. His complaint prompted the government to require the school principal to meet Purnomo, apologize to his daughter, and promise that he would stop the Islamic group from intimidating students.[111]

In Padang, a 19-year-old student told Human Rights Watch that she had tried to refuse to wear a jilbab, but her school had compelled her through threats and intimidation. She said, “I actually refused, but what else could I do? Many of my classmates do not like to wear jilbabs. When they are out of school, they take off their jilbabs.”[112]

In Bandung, Mida Damayanti, a former student at SMKN2 Baleendah, explained that her teachers—especially female teachers and Islamic class teachers—had enforced the jilbab rule and reprimanded students who did not wear their jilbab in a certain way during her years there in 2005-2008. She said students felt “unlucky” if they had the Islamic class or a “hot-tempered” teacher on Fridays. It would mean that there would be no space for them to take off their jilbab or to wear the more traditional kerudung. The school required that the headscarf cover the neck and that girls also wear a long sleeve shirt and big skirt. “The outfit that we wear would directly affect the teacher’s [academic] grading,” she said.[113]

A student at Makassar State University in Sulawesi said that she was surprised when she was confronted for not wearing a jilbab during her one-week orientation program in August 2016. A senior male student asked her religion. She said, “Islam.” The senior told her that Muslim girls should wear a jilbab if “they want to go to heaven.” She told him that it’s a public university and there was no such regulation. More seniors joined in, threatening not to pass her out of the orientation program. She explained that two other Muslim girls also did not wear a jilbab. The students running the program threatened all three with expulsion from the program. The three finally succumbed, planning to take off their jilbabs after the orientation program ended. But they later learned that some university lecturers act against students who do not wear a jilbab on campus. “Only Christian students have the freedom not to wear a jilbab,” she said. They finally decided to keep wearing the jilbab on campus but take it off once they left campus.[114]

A psychologist who comes from one of Indonesia’s elite families in Yogyakarta spoke about her concerns for her teenage daughter:

My family is a Nahdlatul Ulama family [the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia], but my father and mother never pressured me to wear a hijab. And I do not want to pressure my own daughter. Her ethnic Chinese friends have already shared stories about how they were compelled to wear hijab in state schools…. This mandatory hijab [rule] with all the pressure affects our daughters’ mental health. How do we measure [the psychological stress]?

I want to protect my daughter. My husband even told her to go to a Catholic school. I disagreed because Catholic schools also create the impression that Muslims are a threat. Many Catholics are afraid of the Muslims in Indonesia …. We do not have many choices in Yogyakarta. We will either send her to an international school or a private multicultural school. The school fees are more expensive. I am worried to see this trend in Indonesia.[115]

Ifa Hanifah Misbach, a psychologist in Bandung, who often helped students who had been subjected to “jilbab bullying” and suffered from a condition she called “body dysmorphic disorder,” talked about the emotional distress many Muslim schoolgirls face, particularly in conservative regencies like Indramayu, Cianjur, Sukabumi, and Tasikmalaya in West Java. She argued that it is in “the best interests” of the children for the Indonesian government to reconsider policies and practices that lead to mandatory hijab wearing in Indonesian schools: “If our bodies are hurt, we can diagnose the problem and cure them. But if our mental health is hurt, how do you handle it? We never know the scars that we have created with these intense school and office pressures.” [116]

An 18-year-old said that she was compelled to wear a jilbab from the time she went to kindergarten in Solok: “My teachers argued, ‘It’s for educating very little girls about jilbab, covering their bodies.’ You could imagine being a little girl, wearing a jilbab; it was frightening when teachers began checking our jilbabs.”[117]

One mother in Banyuwangi complained to Human Rights Watch that her 6-year-old daughter was compelled to wear a jilbab in a public kindergarten in 2012.[118] The teachers, without asking the parents, put a hijab on all the little girls for a class photo. “I protested, telling the teachers that these little girls should not be compelled to wear jilbab.”[119]

Punishing Girls with Demerits, Markers, and Scissors

Many schools regulate headscarves to the tiniest detail, specifying that the fabric should not be transparent, no hair should show, and girls cannot have a hair-bun. Some schools use measures that stigmatize girls, damage their clothing, and even threaten them with expulsion for not wearing the jilbab to enforce its wearing. Yet, many girls deliberately wear thin and shorter headscarves as a form of daily resistance.

In many schools, every time a student is considered to have breached a school regulation—including the jilbab regulation—she gains some demerits. If a student’s points reach a certain level, the student will get a formal warning. As the demerit levels rise parents are summoned to school. Ultimately, a student can be expelled, a school supervisor in Solok, West Sumatra, explained to Human Rights Watch, showing samples from that school’s rules.[120]

For example, a school regulation at SMAN3 Solok includes multiple sanctions, including two demerits if a student wears “a transparent jilbab” and another two demerits if she wears “a tight skirt, a mini skirt or a split skirt.” The regulation specifies that female clothing must cover the “hips and not be tight…. The jilbabs must not be transparent.” During gym class, female sports uniforms “must not be tight, not have pencil-shaped pants, and the jilbabs must not be transparent.”[121]

A woman in Solok, now 27, recalled her experience with the demerit system:

If you reach 100 points, you will be expelled [diminta mengundurkan diri] from school. The headscarf must be thick, no hair is to be seen, and the jilbab must be broad enough to cover the chest. The shirt must be long enough to cover the hips. Those who wear shorter, thinner jilbabs, showing their hair, will be reprimanded, summoned to the counselling office, then given demerits. If the jilbab is too thin or too short, the teachers will [draw a large] cross with markers on the shirt or the headscarf. Likewise, a shirt that does not cover the hips will be crossed.[122]

Schools often hesitate to expel students because grants programs (Bantuan Operasional Sekolah) are linked to the number of pupils in the school. To avoid the loss of operational grants and a potentially long bureaucratic dispute with complaining parents, many schools use markers on girls’ clothes to stigmatize students who do not wear a jilbab. Said a student in Padang:

There’s a demerit system. If you keep violating the rules, you could accumulate the maximum 100 points and be expelled from school. Those who dare to violate these jilbab provisions are usually my Muslim friends. Most of them end up wearing headscarves [most of the time] because of school rules. Outside of our school, they do not wear jilbabs. Luckily, none of my classmates were expelled from school.[123]

In Tasikmalaya, West Java, a 16-year-old student at SMAN9 said she and her classmates were forced to wear a jilbab at the school. Students who wear the school skirt but allow their socks to show around the ankle get 40 points. If a student accumulates 500 demerits, the school can expel the student. “Everyone was compelled to wear jilbab,” she said. “No other option.” She explained that when she was not at school, she did not wear a jilbab and went out in shorts.[124]

Human Rights Watch documented five separate cases in which the demerits led parents to move their daughters to other schools; usually these were private, fee-paying schools. This not only imposed an economic cost on the families but had negative impacts on learning and friendships. Many reported social stigmas.

In Solok, a mother said she had no choice but to move her daughter Fifi after her demerit had reached 75 of 100 points in only one semester because she did not wear the approved jilbab. Fifi was very likely to be expelled from the school. The mother said:

In 2013, my daughter often wore a brown jilbab as part of her Pramuka [Girl Scout] uniform that was considered too thin. Every time she wore that thin jilbab, she got five demerits. The thin jilbab was comfortable. The school requires a thick jilbab, but it’s uncomfortable. In the first semester she already got 75 demerits. I was worried that she might be expelled. I decided to move her to a private school.[125]

On October 19, 2017, a 16-year-old student at SMKN4 vocational state school in Bandar Lampung, Sumatra, was summoned to meet her teachers after she had repeatedly taken off her jilbab during school. She said that two female counsellors had previously threatened to shave her head. She used her mobile phone to record the 19-minutes of intimidation she experienced and told Human Rights Watch:

I was summoned to the school counselling room. I turned on my recorder. There were some teachers inside the room including the school counsellors. I just remembered some teachers—one male and the two females—plus one female teacher and four male teachers [who did not say anything]. The male teacher was a senior school counsellor. They all commented about my rejection of the jilbab. Mr. [name withheld]) suggested that the school expel me. Miss [name withheld] and Miss [another teacher] denied that they had ever threatened to shave my head. They asked me if I had a recording of that threat.

I tried to challenge them, “Is this a state school or an Islamic madrasah?” A senior teacher walked towards me and roughly held my face. She told me she wished I would die in the next three months if I fabricated a story about being threatened by the teachers. Finally, I was let go.[126]

The student called her parents in Jakarta and begged them to remove her from the school. They tried to console her, asking her to calm down and promising to send her uncle and aunt, who lived in Bandar Lampung, to visit the school. They also asked her to persevere since she would graduate in four months. Said the student:

On October 27, 2017, my uncle and aunt came to school. The counselling teacher refused to meet with them because they were “not real parents.” “You said your parents would come here, not your uncle and aunt,” she said. But my uncle and aunt insisted. They came into the room and told Miss [name withheld] they just wanted to talk. Miss [name withheld] and Miss [name withheld] finally agreed to talk to them. The teachers claimed they were not making any threats whatsoever. They said I was making it up. Finally, I showed them the voice recording. They didn’t say anything.[127]

The student sent her 19-minute recording of the meeting with the teachers to Human Rights Watch. The aunt verified the recording and told Human Rights Watch that she had planned to report the school to the Bandar Lampung police but decided not to after considering the “emotional nature” of some Muslim residents in Bandar Lampung. As her niece was also about to finish school, she and the school had made a compromise that she would not be intimidated again.[128]

A 16-year-old high school student in Solok said some of her teachers cut students’ shirts if they fit their bodies too closely: “First you lose some points. Then the teacher asks [the student] to tug off her shirt and cuts the shirt. [The student] then sews it up again, but looser, and the following day the teacher checks.”[129]

In Solok, a student at SMAN3 talked about how her teachers had used scissors to cut the girls’ clothes:

If the pants are pencil-shaped [for sports], they cut them this long [gesturing toward her knee] … near the seam. Now from grade 10, they are wearing trouser-skirts. This is a new regulation for sports. Underneath they wear trousers but on the outside it’s a long skirt, but open so you can run.

They cut the trousers because they were too tight, because of the pencil shape. But many of my friends sewed them up again. The teachers wanted them to buy new pants, loose pants, not body-hugging pants. The teachers would cut the pants again and you’d get points. [Your] points would get higher and higher. Each cut was five points.[130]

In Muaraenim, South Sumatra, a male teacher reportedly used scissors to cut the hijabs of several female students after a school assembly when he determined that their hijabs did not meet the school’s requirement. After he cut their hijabs, he sent them home to change their hijabs.[131]