(São Paulo) – Brazilian authorities should ensure that Brazilians can exercise their right to vote freely and safely in the October 2022 elections. Federal and state authorities should protect voters, candidates, and electoral workers and volunteers, including by enforcing temporary gun restrictions.

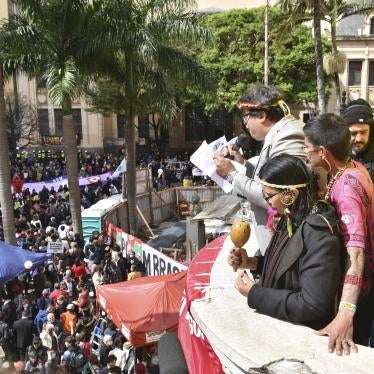

About 156 million voters will elect a president, governors, and federal and state legislators on October 2. Runoffs for president and governors, if no candidate obtains more than 50 percent of valid votes, will take place on October 30. Political violence, harassment of journalists, and attempts to undermine trust in the electoral system have all increased in the run-up to the election.

“Online and offline hate speech and harassment and serious political violence have made many Brazilians afraid to express political opinions and exercise their political rights,” said Juanita Goebertus, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “Electoral and judicial authorities, police forces, and other authorities should do their utmost to protect freedom of speech and assembly, and ensure that Brazilians can vote safely.”

Three supporters of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who is running for president, were killed, one in July and two in September, allegedly for their political positions. President Jair Bolsonaro was stabbed during the 2018 election campaign.

The Observatory of Political and Electoral Violence at Rio de Janeiro’s Federal University compiled 214 cases of threats and violence against individuals engaged in politics or their relatives from January through June. Women candidates, especially Black and trans women, are particularly likely to receive threats and online harassment, available data show.

In a poll released on September 15, almost 70 percent of Brazilians surveyed said they were afraid of suffering violence because of their political opinions.

Journalists covering the elections have been harassed by candidates of various political parties. The non-profit Reporters without Borders (RSF) and the Federal University of Espírito Santo identified more than 2.8 million social media posts with offensive content against the media during the first three weeks of the current electoral campaign. The study also found that reporters, particularly women, were targeted for online harassment by supporters of President Bolsonaro after he publicly insulted them.

All candidates should condemn political violence, refrain from harassing reporters, and call on their supporters to respect the right of Brazilians to peacefully elect their representatives and to run for office without fear, Human Rights Watch said.

Other statements by President Bolsonaro appear to be intended to undermine trust in the electoral system. Elections in Brazil are overseen by the Superior Electoral Court, headed by a Supreme Court justice. In June, President Bolsonaro said it “appears” that election winners will be those “who have friends” in the Superior Electoral Court

In remarks in July to a large group of ambassadors, he claimed without providing evidence, that Brazil’s electoral system was unreliable. On September 18, he said that if he does not get 60 percent of the vote, “something wrong would have happened within the TSE,” referring to the Superior Electoral Court by its Portuguese initials.

Brazil adopted electronic ballots nationwide in 2000, and there have been no confirmed cases of electoral fraud since, according to a Superior Electoral Court representative.

On September 22, eight UN rapporteurs warned of the increase of political violence in Brazil and called on Brazilian authorities to protect electoral institutions and candidates, and ensure that “everyone can participate freely in the electoral process.”

In an indication of the risk of violence during the election period, the Superior Electoral Court has prohibited carrying guns in a 100-meter area around polling places on and immediately before and after election day. On September 9, Supreme Court Justice Edson Fachin also temporarily suspended portions of presidential decrees that had made it easier to buy and carry guns, citing the risk of political violence. Gun ownership has substantially increased in Brazil since the decrees went into effect.

The Superior Electoral Court has created an intelligence unit, in cooperation with state police forces, to combat political violence and has approved the deployment of the Armed Forces in more than 500 municipalities in 11 states, upon request by state officials. Their mission is restricted to ensuring the safety of elections material and protecting voters and election workers.

The UN Human Rights Committee has stated that voters should be free to form opinions “free of violence or threat of violence” and must be able to vote “without undue influence or coercion of any kind.” Guidelines on participation in public affairs issued by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights provide that “States should take measures to protect the safety of candidates, particularly women candidates, who are at risk of violence and intimidation.”

International human rights law calls for authorities to uphold free expression and peaceful assembly. Law enforcement should only restrict peaceful assembly to the extent necessary and proportionate to a legitimate goal, such as protecting the rights of others, including the right to vote.

In the face of warnings by judges of possible violence, it is paramount for the police to maintain law and order. This should include responding to any acts of violence during demonstrations in full compliance with the principles of proportionality, legality, and necessity, and enforcing the judicial rulings on gun restrictions during the elections.

International standards establish the duty of the state to protect the public. Under the UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, police “shall at all times fulfill the duty imposed upon them by law, by serving the community and by protecting all persons against illegal acts.”

In a September 21 joint letter, five civil society organizations, including Human Rights Watch, called on state prosecutors to ensure that police carry out their duties during the elections, and to require the police to make public their plans to guarantee security on election day.

“Foreign governments should support free and fair elections in Brazil,” Goebertus said. “The international community should stand with the Brazilian people and unequivocally reject any attempt to disrupt the right to vote and to deprive them of their right to freely choose their representatives.”