Amnesty International is an international non-governmental, non-profit organization representing the largest grassroots human rights movement in the world, with more than ten million members and supporters. Amnesty International’s mission is to advocate for global compliance with international human rights law, the development of human rights norms, and the effective enjoyment of human rights by all persons. It monitors state compliance with international human rights law and engages in advocacy, litigation, and education to prevent and end human rights violations and to demand justice for those whose rights have been violated.

The Global Justice Center (GJC) is an international human rights organization, with consultative status to the United Nations, dedicated to advancing gender equality through the rule of law. GJC combines advocacy with legal analysis, working to ensure equal protection of the law for women and girls.

The Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative for Economic and Social Justice (SRBWI) is a human rights organization, formed in 2001 to address historical race, class, cultural, religious and gender barriers faced by Black women and young women in the rural U. S. South. A collective of women led organizations across Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia, the SRBWI is dedicated to honoring the achievements of our ancestors by continuing their efforts to push our communities forward.

Human Rights Watch is an independent, international non-governmental organization that investigates and reports on rights violations in over 100 countries worldwide. Human Rights Watch documents and reports on human rights abuses and directs advocacy toward governments, armed groups, and businesses, pressing them to change or enforce their laws, policies, and practices to respect and uphold rights for all people.

Table of contents

US abortion restrictions are a form of racial discrimination.

Forced travel for abortion is more difficult for women of color

Judicial bypass restrictions disproportionately impact young people of color

Coerced pregnancy and childbearing are more dangerous for women of color than for white women.

Forced motherhood enforces lower socioeconomic status for women of color individually and as a class

Recommendations to the State Party:

Recommendation to the State Party:

Introduction

“Racism in America is more than the fire hoses, police dogs and Alabama sheriffs you envision when you hear the words,” writes Petula Dvorak.[1] It is also the tyranny inflicted on racialized women when they are stripped of their reproductive autonomy, shackled while giving birth, and excluded from lifesaving health care and information on cervical cancer.

This submission under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) discusses three sites of systemic racism[2] and intersectional discrimination that oppress women of color, particularly Black women, in the United States (US): abortion restrictions, the shackling of pregnant prisoners, and racial inequalities in cervical cancer mortality. While many of the laws and practices described in this submission do not directly target women of color and are presented in facially neutral terms, they disproportionately impact the human rights of women of color. We urge the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD, or the “Committee”) to recognize the disproportionate effects of these policies on the lives of racial minorities and the racial inequalities that they perpetuate.

US abortion restrictions are a form of racial discrimination

- In June 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States overturned the constitutional guarantee to access abortion.[3] As a result, more than half of US states are poised to ban abortion; as of July 7, 2022, thirteen states have already criminalized or severely restricted abortion.[4] Anti-abortion regulations affect all women and people who can become pregnant, but health inequities and racialized socio-economic inequalities mean that it is women and adolescents of color whose disproportionately suffer.

Abortion is a form of reproductive health care needed by women of color at higher rates than white women

- Abortion restrictions disproportionately impact women of color in the US because abortion is a type of health care that is needed by women of color more frequently than white women. According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (the US national health protection agency), among the areas that report abortion numbers by race, the largest percentage of abortions were needed by Black women, who accounted for thirty-eight percent.[5] Hispanic women accounted for twenty-one percent and white women accounted for twenty percent.[6] While people need abortions for numerous and often interrelated reasons, most abortions are needed due to unintended pregnancies[7] and women of color experience unintended pregnancies at higher rates than white women.[8] This is due in significant part to the economic, social, and geographic barriers that limit access to health care, including to contraception, for women of color. Because contraception is expensive, it is most accessible to people who have health insurance, and women of color are more likely to be uninsured than white women.[9] For example, on average, seventeen percent of Black, Latina, and Indigenous women of reproductive age lack health insurance.[10] In some states, it is even higher—twenty-five percent of Black women in Mississippi are uninsured.[11] By comparison, twenty percent of white women lack insurance.[12] Even for those with insurance, the most effective forms of contraception often have up-front, out-of-pocket costs that may be prohibitive for poorer women. Additionally, over-the-counter emergency contraceptives are not covered by insurance. The often-prohibitive cost of contraception contributes to higher rates of unintended pregnancies and, in turn, a greater need for abortion care among women of color.

- Another factor contributing to greater need for voluntary termination of pregnancy among women of color is the higher rates of intimate partner violence[13] and “reproductive coercion”[14]—deliberate attempts, usually by intimate partners or other family members, to control a person’s reproductive choices.[15] As the World Health Organization has consistently highlighted, intimate partner violence during pregnancy is associated with adverse health outcomes for the pregnant person.[16] Abortion is often the safest option for pregnant people experiencing intimate partner violence, and, given that women of color experience such violence at higher rates than white women, restrictions on abortion inordinately deny women of color a form of care that they disproportionately need.[17]

Forced travel for abortion is more difficult for women of color

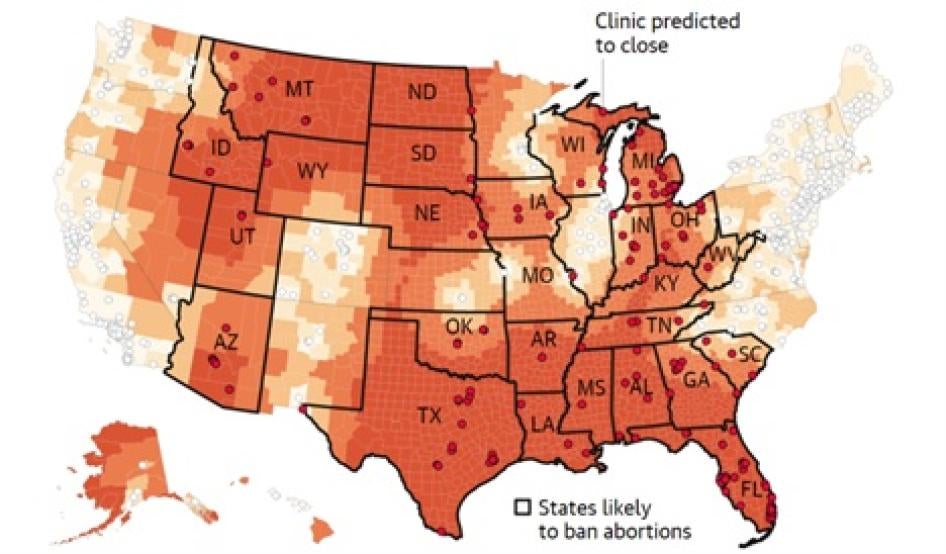

- The expanding legal restrictions on abortion in the US mean that hundreds[18] of reproductive healthcare clinics across the country are being forced to close, and in fact, many already have. As a result, people who live in states that ban or severely restrict abortion must travel to states where access is less restricted for clinical abortion care.[19] Millions of people now live in “abortion deserts” and must travel hundreds of miles to access clinical and/or legal abortion care.

- Forcing women to travel long distances or across state borders disproportionately impacts women without means owing to the financial cost combined with difficulties such as taking time off work, arranging childcare, and securing transportation and lodging.[20] For example, an analysis of the Texas abortion ban showed that it would lead to a 14-fold increase in driving distance to the nearest abortion clinic and cost the equivalent of a full-day’s earnings for someone making minimum wage “solely to pay for the additional amount of gas for each round trip.”[21] Critically, owing to the structural inequalities and intersecting discriminations caused by race, class, and gender in the US, burdens on poor women translate to burdens on women of color.[22] Women of color are more likely to fall below the poverty line[23] and have a lower socioeconomic status[24] than white women and therefore acutely feel the costs of interstate travel for health care. Studies already demonstrate that the burden of travel is more difficult to overcome for women of color; according to data based on state-level abortion restrictions before 2021, an increase in travel distance from 0 to 100 miles increases births for Black women by 3.3 per cent versus by 2.1 per cent for white women (suggesting that a greater number of white women were able to travel for abortion).[25]

- Additionally, for pregnant people with irregular migrant and/or asylum status (a population that is largely non-white in the US)[26] forced interstate travel for abortion is fraught with the additional challenge of policing and immigration control. Amongst the million immigrants who live under one of the country’s most aggressive abortion bans in Texas,[27] the combination of lack of resources and border patrol checkpoints means that pregnant people who are undocumented are largely unable to travel to out-of-state providers.[28]

Judicial bypass restrictions disproportionately impact young people of color

- Even in some states where abortion remains legal, pregnant women and all other pregnant people— whether they are traveling from other states—will face significant obstacles in accessing timely care. For example, abortion is currently legal in Florida,[29] but the state recently imposed both a 24-hour waiting period and a 15-week ban[30]—restrictions that will disproportionately harm people with lower socioeconomic status and people of color, for the reasons described above. Even some states more protective of abortion rights maintain certain restrictions with racially disproportionate effects, such as parental involvement laws[31] that require people under 18 to involve a parent in their abortion decision or seek permission from a judge to have an abortion without involving a parent (“judicial bypass”). Human Rights Watch research with the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois, for example, found that most young people who had gone through judicial bypass in Illinois and experienced the harms associated with it were Black, Indigenous and other young people of color.[32] (In October 2021, Illinois repealed its parental involvement law, a move to defend young people’s rights and dignity.) Similarly, a 2019 study in Massachusetts found that judicial bypass of the state’s parental consent law “disproportionately involves minors who identify as racial or ethnic minorities, and who are of low socioeconomic status.”[33]

Coerced pregnancy and childbearing are more dangerous for women of color than for white women

- Despite their efforts to overcome the legal, geographic, and economic barriers to abortion access, many women, girls, and people capable of becoming pregnant are nonetheless forced to maintain unwanted pregnancies and birth children against their will. This severe violation of human rights carries deadly risks for women, especially Black women. Research carried out before the Supreme Court decision estimated that a total abortion ban would lead to an increase in pregnancy-related deaths for all women, but that Black women would bear an outsized mortality risk: a thirteen percent increase in pregnancy-related deaths for white women and a thirty-three percent increase among Black women.[34] As it stands, Black women are three times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related causes in the US.[35] In some parts of the country, the mortality rates for Black women are even higher – in Mississippi, Black women accounted for “nearly 80 percent of pregnancy-related cardiac deaths” from 2013-2016.[36] The expansion of abortion bans means that states in the US are about to subject millions more Black women to potentially life-endangering pregnancies against their will. The State party is risking their lives.[37]

- Notably, a substantial body of research affirms that racial inequality is the fundamental reason for women of color’s heightened risk of maternal mortality and morbidity, including racial disparities in preexisting comorbidities.[38] The differences in the quality of care that women of color receive as compared to white women[39]; inequities in the social determinants of health, such as poverty and healthcare access[40]; and healthcare-provider bias, both explicit and implicit, have all been shown to contribute to the racially disparate maternal mortality rates for women of color. The submission by our colleagues at the Black Mamas Matter Alliance and the Center for Reproductive Rights discusses this crisis and its racial underpinnings at greater length, and we urge the Committee to examine the issue further there.

Forced motherhood enforces lower socioeconomic status for women of color individually and as a class

- The legal status of abortion can define the extent to which pregnant women and all other pregnant people are able to complete their education, participate in the workforce, and play a role in public and political life.[41] As such, when states succeed in forcing pregnant people to carry unwanted pregnancies to term, not only do they violate the rights to health, autonomy, bodily integrity and life (in some circumstances) of pregnant people, they also impose significant and long-term economic and social costs.[42] Women of color, however, are disproportionately affected by the economic fallout of forced childbearing for two overlapping reasons. First, and as just described, women of color living in abortion-restrictive states are less likely to be able to travel for abortion care and are therefore more likely to be coerced into childbearing and rearing. Second, women of color are already more likely to live below the poverty line,[43] receive low wages,[44] experience unemployment[45] and suffer labor discrimination[46] than white women. Consequently, the economic costs and unpaid care burden of forced parenting are more challenging for women of color (and their families) to bear or to overcome. This is particularly true in the states that have the most restrictions on abortion access[47] because these states provide the least economic or care support to parents or children. None offer paid family leave. Seven have no state-funded housing assistance program.[48] In ten of these states, almost one in five children live below the poverty line.[49]

- The failure of these states to provide even minimal support to help raise children inflicts financial insecurity on millions of women and their families, and this will only increase. As a recent study by US economists noted, a hypothetical woman working full-time and making fifteen dollars per hour (which is more than double the federal minimum wage) faces infant childcare costs that total one-third of her gross pay.[50] But systemic racism in the US means that the economic burden of forced parenthood impairs the socio-economic status of Black, Indigenous and Hispanic women individually and as members of a disadvantaged class. By increasing the socio-economic disadvantages endured by many women of color and their families, forced childrearing compounds existing racialized economic disparities. As such, laws and policies that force women and girls of color to bear the economic costs of children against their will, confines millions of women of color to a lower socio-economic class.

Racial bias in the criminal legal system means that women of color are most at risk from abortion and pregnancy criminalization

- Systemic racism in the US criminal legal system[51] means that women of color face a heightened risk of criminal prosecution for abortion (including suspicion of abortion) and as compared to white women. This risk will outright deprive some people from accessing abortion. Others will experience loss of their physical liberty under the criminal legal system.

- The restrictive abortion regime in the US has created an environment in which pregnant people, particularly Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous women, are already policed and criminally punished for pregnancy outcomes. Prosecutors currently use a vast array of criminal and civil laws to penalize pregnant people for engaging in behavior that produces—or creates a risk of producing—a negative birth outcome, such as miscarriage or stillbirth.[52] At least one pregnant Black woman was indicted by a grand jury for manslaughter for the death of her fetus after she was shot in the abdomen by another woman.[53] Some states have subjected pregnant people to criminal punishment and civil constraints for doing things that would be legal if done by a person who was not pregnant — including falling down steps[54] or attempting suicide.[55] Others pursue people for so-called “fetal abuse” using charges such as murder, manslaughter, feticide, child abuse, child endangerment, and chemical endangerment.[56]

- In one especially egregious and emblematic case, a multiracial woman with eight children, served four years in prison after experiencing a stillbirth.[57] Prosecutors asserted that her stillbirth was due to methamphetamine use even though research does not support the claim that methamphetamine causes stillbirth or causes risk of harm different from other activities.[58] Fearful that she might be convicted of murder, Pérez pleaded guilty to a manslaughter charge and was sentenced to 11 years in prison.[59] It took over four years for her case to be dismissed.[60]

- While pregnancy-related arrests and prosecutions are happening across the nation —between 2006 and 2020 there were nearly 1,300 criminal investigations of pregnancy outcomes[61]— officials have mostly targeted and charged Black and brown women.[62] Amnesty International has documented that drug testing of pregnant women is applied selectively, often based on discretionary “risk” factors such as low income, an indicator that frequently applies to women of color.[63]

- The needless and cruel vilification of women of color who suffer pregnancy loss[64] portends the imminent risk of criminal sanctions for women who end their own pregnancies. Now that the US Supreme Court has overturned constitutional protections to access abortion, states are free to criminalize abortion. And because the criminal legal system in the US already disproportionately polices women and girls of color[65] this is the population that will shoulder the brunt of increased surveillance and criminalization of abortion and pregnancy outcomes.[66]

- Criminally punishing pregnancy outcomes, including miscarriage and abortion, is a gross violation of human rights for any pregnant person. But for women of color at the intersection of gender and racial discrimination in the US, the increased efforts to punish and police women’s bodies are magnified. Abortion and pregnancy criminalization constitutes the latest frontier of the US’s mass incarceration crisis with women of color at its center. Understood in this way, anti-abortion policies not only discriminate against individual women of color but also perpetuate the conditions that sustain racial inequality.

Damaging the health and lives of Black and brown women in Global South middle- and low-income countries

- US anti-abortion policies have devastated the lives of women of color abroad. Because the US is the largest foreign aid donor globally,[67] it has an outsized influence on healthcare provision, including the type of health care provided, in many Global South countries. Accordingly, a US policy — the Helms Amendment — that prohibits US foreign assistance funds to pay for abortions (in nearly all circumstances)[68] severely undermines access to abortion for women in the Global South. The consequences for women’s and girls’ lives and bodies are stark. It has long been demonstrated that failure to provide abortion services in the public health system in developing countries drives women and girls to undergo unsafe abortions - often with devastating results.[69] In regions where US funding for global health is critical to budgets for reproductive health services, such as Africa and Latin America, up to seventy-five percent of abortions are unsafe.[70] By banning foreign assistance for abortion, the Helms Amendment contributes to the toll unsafe abortion has on the rights and lives of women in low and middle income countries.

- Remarkably, the Helms Amendment has also overridden national policies on abortion in countries receiving aid. As a recent study indicates: “Of the 56 countries receiving U.S. global health assistance, most (86%, or 48 countries) allow for abortion in at least one circumstance.”[71] But with dependency on US funding to close the healthcare budget deficits, US funding requirements often take the place of national policy.[72] In Nepal, for example, the Helms Amendment “impeded government efforts to improve access to care for women and train providers, led to fragmentation of basic health services, and unnecessary censorship at all levels.”[73] In addition to frustrating national health goals, the policy impedes the implementation of hard-won reproductive rights.

- The Helms Amendment has particularly devastating consequences on Black and brown women in conflict settings by preventing survivors of sexual and gender-based violence from accessing abortion.[74] In practice, the Amendment has been actually over-implemented as a total ban on abortion, ignoring congressionally permitted exceptions in cases of rape, incest, and life endangerment.[75] This US ban compounds the violence endured by women in conflict settings by directly and indirectly contributing to “pregnancy complications, unsafe abortion, and maternal deaths.”[76] In one emblematic and harrowing situation in Democratic Republic of Congo—where the US funds most humanitarian response clinics—a 14-year-old girl who had been raped was denied an abortion due to US funding restrictions. She later died from an unsafe abortion after failing to find a safe service option.[77]

- While the Helms Amendment applies to populations outside of the United States, it is still a relevant part of US policies for the purposes of examination under ICERD. ICERD’s prohibition of discrimination on grounds of race applies extraterritorially. The State party is required “to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists.”[78] By imperiling the lives and bodies of Black and brown women, the Helms Amendment perpetuates racial discrimination and discriminates in access to health care in violation of ICERD.

Conclusion: US abortion law and policies violate the right to health (Article 5 (e)(iv)) and perpetuate racial inequalities (Article 2) of the ICERD.

Recommendations to the State Party:

- Take federal and state legislative steps to guarantee effective access to affordable, legal, and quality abortion care.

- Declare a national public health emergency to enable out-of-state prescription and dispensing of medication abortion and to shield providers and others from liability for their involvement in providing medication abortion.

- Protect pregnant people from criminalization related to pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, including miscarriages, stillbirths, and abortions.

- Ensure equitable, federal access to medication abortion to all people, regardless of the presence of restrictive laws in a patient’s state of domicile.

- Repeal laws that require young people seeking abortions to notify or obtain consent from parents to receive abortion care or that require them to undergo judicial bypass procedures.

- Provide access to comprehensive abortion care within the jurisdiction of the federal government, including in states where abortion bans are in effect.

- Mitigate all civil and criminal risks to providers and patients receiving care within federal jurisdictions, including by granting civil immunity to medical providers practicing in states in which they do not hold a license.

- Remove the remaining medically unnecessary Federal Drug Administration restrictions on medication abortion, including the requirement that physicians and pharmacies be certified to prescribe and dispense the medication and that patients must sign an agreement that they understand the drugs’ risks.

- Remove the Helms restrictions on U.S. foreign aid and amend the Foreign Assistance Act to ensure that development assistance and global health funds provide safe and quality abortion care and information.

Shackling of incarcerated pregnant persons violates the right to health and perpetuates anti-Black discrimination

- The United States reports the highest incarceration rate in the world (664 per 100,000 people in 2021)[79] and incarceration is marked by extreme racial disparities.[80] The population of incarcerated women is growing at twice the rate for men,[81] and women belonging to racial minorities are disproportionately represented in this population. For example, in 2019 the incarceration rate for Black women was 83 per 100,000 people, over 1.7x the rate for white women (48 per 100,000).[82] Latina women were incarcerated at a rate of 63 per 100,000.[83] Native women make up 2.5 percent of incarcerated women in the US, despite being only 0.7 percent of the total US female population.[84]

- Though the US incarcerates more women than any other nation in the world, the distinct human rights abuses women suffer in prison receive relatively little attention. The barbaric practice of shackling pregnant detainees[85] and prisoners, including during labor, delivery, and postpartum recovery, is ill treatment that can amount to torture based on gender and racial discrimination, as well as its potential to cause severe mental and physical pain. Though shackling has long been recognized as a human rights violation by successive UN bodies,[86] the dehumanizing practice persists and federal efforts to end the practice have had limited impact. Most US states have adopted some form of restriction on shackling, but 11 states have no restrictions at all on the practice.[87]The practice remains prevalent despite existing efforts: a 2018 study of perinatal nurses in the US found that among those who worked with incarcerated pregnant women, 82.9 percent reported that their incarcerated patients were shackled “sometimes” to “all the time,” and 12.3 percent said that their incarcerated patients were always shackled.[88]

- Because Black women are nearly twice as likely to be incarcerated as white women, they are also disproportionately subjected to shackling. Additionally, the practice is a direct descendent of the subjugation and confinement of Black women during slavery, as well as in the racist post-Civil War carceral systems that have influenced modern US prison policies. [89]

- As a vestige of slavery, shackling is a form of racial discrimination against Black women. As the scholar Priscilla Ocen writes, the practice of shackling is itself a “manifestation of the punishment of ‘unfit’ or ‘undesirable’ women for exercising the choice to become mothers. Within the prevailing punishment regime, undesirability is synonymous with race, as the impulse to punish such women is rooted in the stereotypical constructions of Black women.”[90]

- Shackling is unnecessary. The practice is frequently justified under the guise of preventing escapes and protecting corrections officers and medical staff from violence, but the reality is that most women prisoners are incarcerated for nonviolent crimes and as such pose a low security risk.[91] In addition, during labor, delivery, and immediate postpartum recovery a person is barely able to walk, let alone escape from custody. Only 9.7 percent of respondent nurses in the 2018 study reported ever feeling unsafe with incarcerated pregnant women.[92]

- Given the disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality for Black women, shackling is also potentially a violation of the right to life. It can delay timely medical interventions during labor and dangerously limits an individual’s ability to move during delivery, especially in the final stages of labor where it is imperative for physicians to be able to act quickly.[93] It can also worsen preexisting mental health conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder and depression and can cause postpartum depression.

- Leading US medical organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists[94] and the American Medical Association,[95] acknowledge the severe negative health impacts of shackling and strongly oppose the practice. The American Psychological Association also supports an end to shackling, noting that the practice affects women of color disproportionately and that shackling can “cause or exacerbate pregnancy-related mental health problems” for a population in which high rates of mental health problems already exist.[96]

- Multiple US courts have affirmed the harms of shackling. As one federal court found, Shawanna Nelson, who had been shackled during delivery, suffered “extreme mental anguish and pain, permanent hip injury, torn stomach muscles, and an umbilical hernia requiring surgical repair,” as well as damage to her sciatic nerve.[97] In another case, an inmate shackled during labor, named Casandra Brawley, was only “unchained long enough for medical staff to insert the epidural, and then re-chained to the bed”; later, when doctors decided to perform an emergency cesarean section, her leg restraints were removed just prior to surgery, and she was chained to her bed again “right after surgery before she could even feel her legs.”[98]

- International law also prohibits shackling. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Mandela Rules)[99] and the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (Bangkok Rules) both explicitly prohibit the practice. Both the Committee against Torture and the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment have criticized the use of shackling, including in the US, and called for a definitive end to its use.[100]

- The horror of shackling pregnant women is an acute concern. The number of women in US jails and prisons is growing at a rate twice as high as that of men,[101] and up to 58,000 pregnant people enter jails or prisons every year.[102]

Conclusion: The shackling of pregnant persons in prisons and detention centers violates the right to health (Article 5(e)(iv)), the right to security of person and protection by the State against violence or bodily harm, whether inflicted by government officials or by any individual group or institution

(Article 5(b)) and amounts to a practice of racial discrimination against persons (Article 2) of the ICERD.

Recommendation to the State Party:

- Eliminate the practice of shackling pregnant women and all other pregnant people in jails and prisons and standardize human rights compliant care for incarcerated pregnant people.

Racially disparate mortality rates for cervical cancer

- The CERD has noted the persistence of racial disparities in the field of sexual and reproductive health, particularly regarding the high maternal and infant mortality rates among African American communities.[103] Persistent racial disparities permeate other issues of sexual and reproductive health, including mortality from cervical cancer. Cervical cancer thrives in the US in a context of structural racism, discrimination, poverty, and inequality. It is highly preventable and treatable yet Black women in the US die at disproportionate rates.[104] The United Nations expert on extreme poverty recently sharply criticized the US and cited cervical cancer as one example of how persistent racial discrimination has made the burdens of poverty even worse for many women.[105]

- Over 4,200 women die of cervical cancer each year in the US,[106] which is nearly six times the number of pregnancy-related deaths each year.[107] Black women have a higher risk of late-stage diagnosis, are less likely to receive adequate treatment, and are more likely to die from the disease than any other racial or ethnic group in the country.[108] Black women are almost twice as likely to die from cervical cancer as white women in the US.[109] Racial disparities are even greater when national data is corrected to exclude women who have had hysterectomies, with the greatest disparities impacting older Black women.[110]

- Economic deprivation is strongly and independently associated with cervical cancer mortality and women from poor communities have a higher risk of late-stage diagnosis and lower rates of cervical cancer survival than those from more affluent communities in the US.[111] But racial disparities in cervical cancer deaths are not reducible to disparate income levels. Studies have found that controlling for socioeconomic status reduces the higher cervical cancer mortality risk for Black women, but it does not erase it entirely.[112] Even among women with similar stages of the disease, Black women are less likely to receive appropriate treatment due to loss of follow-up, therapeutic delays, and differences in treatment.[113]

Shortcomings in treatment and diagnosis for Black women

- In 2017 and 2018, Human Rights Watch investigated the high rates of cervical cancer deaths for Black women in the state of Alabama.[114] At the time, Alabama had the highest rate of cervical cancer mortality, and it was increasing, with Black women dying at nearly twice the rate as white women.[115] However, Alabama had screening rates consistently above the national average and Black Alabamian women were accessing screenings at higher rates than white Alabamian women. Generally, more cervical cancer screenings mean less cervical cancer deaths. The fact that Black women obtained screenings at slightly higher rates than white women contradicts those findings.[116] Rather, experts agree that the lower relative survival and higher mortality rates for Black women are likely due to later-stage diagnosis, treatment differences, and comorbid conditions.[117] The later-stage diagnosis can be explained in turn by failure to follow up on abnormal screenings and diagnostic delays, that is, delays between an abnormal test result and cervical cancer diagnosis.[118] Studies have found that race, along with a host of other factors like age, health insurance status, understanding of HPV, and psychological distress, is correlated with poor follow-up after abnormal Pap tests.[119]

Lack of health insurance coverage is a significant barrier to cervical cancer prevention and care for Black women

- Human Rights Watch research in Alabama found that a lack of health insurance coverage was one of the most significant barriers to cervical cancer care, in a state that did not choose to expand Medicaid under the federal Affordable Care Act (ACA). Further, fewer than half of the counties in Alabama have a practicing gynecologist. Rural women must drive long distances for essential gynecological care, and the cost and burden are often too much. Women described having to choose between reproductive health care and other basic needs such as electricity, medication, and food.[120] Further, programs prioritizing community engagement and education that could help disrupt harmful social norms, connect women to care, and reduce health disparities in cervical cancer outcomes were underfunded.[121]

State failure to provide comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information and services

- Women, providers, and local advocates also reported severe problems with access to health information in Alabama. A vast majority of cervical cancer cases are caused by HPV, a sexually transmitted infection, and many cervical cancer risk factors are directly related to sexual activity.[122] Comprehensive sexual health education has been shown to increase condom and contraceptive use; decrease likelihood of teen pregnancy, HIV or other STIs; delay the initiation of sexual activity; and reduce the number of sexual partners and sex without condoms—all of which would have the effect of reducing cervical cancer risk.[123] The World Health Organization considers condom promotion and heathy sexuality education to be necessary tools for the prevention of cervical cancer.[124] Human Rights Watch research in 2019 and 2020 looked closely at the quality of sexual health education in Alabama and its role in helping prevent cervical cancer deaths.[125] Many Alabama school systems, particularly in the Black Belt, a region of the state already underfunded due to reliance on local property taxes and a legacy of constitutional segregation that de facto continues, often neglect sexual health education. The state does not require schools to provide sexual health education, but if they choose to do so, they are statutorily required to place a heavy emphasis on abstinence– limiting young people’s access to comprehensive and evidence-based information on their bodies and health.[126] The resulting unequal access to information can create lifelong disadvantages for some students, particularly those who are Black and live in poverty, and may contribute to racial disparities in health outcomes as they enter adulthood.[127]

- Like Alabama, the state of Georgia has persistent racial disparities in cervical cancer mortality. Between November 2020 and August 2021, the Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative for Economic and Social Justice (SRBWI) and Human Rights Watch partnered with nine community-based researchers to document factors contributing to disproportionate cervical cancer death rates for Black women in rural Georgia.[128] This research found that Georgia state and local agencies, and the US federal government, are not doing enough to facilitate access to reproductive healthcare services and information to prevent cervical cancer deaths and address racial disparities in health outcomes.

- Georgia does not ensure access to comprehensive and affordable reproductive health care and instead relies on a patchwork of multiple, publicly funded programs to extend healthcare coverage to low-income women in the state, including for gynecological care. Like Alabama and ten other states, Georgia has not expanded Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act to extend healthcare coverage to more low-income individuals. Without a comprehensive plan to guarantee access to consistent and affordable health care, the state has left low-income and uninsured Georgian women—who are more likely to be Black—struggling to navigate gaps in health insurance coverage and enormous financial barriers to cervical cancer care. For many women, especially those who are uninsured, their inability to afford reproductive healthcare services means that they often avoid medical appointments and skip cancer screenings and follow-up care altogether, forgoing lifesaving opportunities to prevent and treat the disease.[129]

Limited access to gynecological care for marginalized women

- Limited access to gynecological care also creates barriers to cervical cancer care for marginalized women, especially those living in rural and underserved areas. Georgia faces a severe shortage of obstetrician-gynecologists and almost half of the state’s 159 counties do not have one. State policies have contributed to the closure of rural hospitals, which has helped fuel this shortage, while the state’s failure to provide adequate public transportation, especially in rural counties, creates additional challenges to obtaining cervical cancer care. For women who must travel long distances for gynecological care and for those who lack adequate transportation, including money for gas or to pay someone to take them to appointments, accessing cervical cancer care is often burdensome, costly, and, at times, even impossible.[130]

Discrimination and bias against women of color in the healthcare field

- Structural racism and discrimination in the healthcare field, coupled with many Black women’s related distrust of medical providers, also impact the quality of care some women receive and their willingness to seek out reproductive health care. SRBWI and Human Rights Watch spoke with women who said they felt that their health concerns were dismissed and the quality of care they received was inadequate because of racism and medical providers’ bias against them as Black women. Many others described how callous treatment, an inadequate level of care, and concerns around confidentiality have undermined the trust they have in doctors, alienated them from gynecological care, and contributed to poor reproductive health outcomes.[131]

- Many Georgian residents, including about a third of the women that SRBWI and Human Rights Watch interviewed, lack information on the HPV vaccine as a cancer prevention tool, and vaccination rates in the state are below the national average. Georgia’s government has not implemented key policies that would support access to and information on HPV, HPV-related cancers, and the HPV vaccine for all residents and has enacted only one supportive policy to increase HPV vaccination rates: licensed pharmacists can administer the HPV vaccine; however, this requires a prescription for individuals under 18.[132] At the same time, as in Alabama, the government is failing to ensure that all young people in schools receive comprehensive, inclusive, and accurate information on their sexual and reproductive health. Inadequate access to this lifesaving information undermines Georgian women and girls’ understanding of cervical cancer and the preventive steps people can take to lower their risk and stay healthy and safe. It also contributes to misinformation, fear, and stigma around sexual and reproductive health that makes many women reluctant to discuss or seek out cervical cancer care.[133]

- Marked racial disparities in cervical cancer deaths in the US reflect exclusion from the healthcare system and unequal access to the interventions and services necessary to prevent and treat the disease, particularly in its early and treatable stages. In failing to address and eliminate barriers to equal, accessible, and comprehensive cervical cancer care—including a lack of affordable healthcare coverage and inequalities in access to life-saving information on sexual and reproductive health—US state and federal governments are failing to protect and promote the rights to health, equality, and nondiscrimination, with particularly devastating impacts on Black women.

Conclusion: Inequalities in treatment for cervical cancer violate the right to health (Article 5(e)(iv)) and perpetuate racial inequalities (Article 2) of the ICERD.

Recommendations to the State Party:

The United States should comply with its obligations under the ICERD to eliminate disparate racial impacts in public health, including racial disparities in cervical cancer outcomes by:

- Supporting US states to promote community health workers and community-based approaches to reproductive health care that address healthcare access and the social determinants of health.

- Establishing inclusivity policies that:

- support linguistic and racial diversity among healthcare providers, including in federally qualified health clinics; and acknowledge, confront, and seek to remedy historic and current experiences of racial discrimination in public health.

- Providing cultural competency, implicit bias, and anti-racism training to address the ways in which structural racism manifests within the healthcare field and impacts the treatment and quality of care patients receive.

- Mandating comprehensive sexual health education in all primary and secondary schools receiving federal funding that is age-appropriate, scientifically and medically accurate, rights-based, and inclusive of all young people and allocate funding for community-based initiatives to ensure information on sexual health reaches young people who are out of school; adopt clear policies that facilitate education around HPV; and address additional barriers that contribute to low HPV vaccination rates.[134]

[1] Petula Dvorak, Listen to Black women. They are outraged, tired and they are right., Wash. Post (June 16, 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/06/16/colin-greene-racial-disparities-healthcare-youngking/.

[2] In her report to the Human Rights Council on human rights violations against Africans and people of African descent by law enforcement officers, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights described “the concept of systemic racism against Africans and people of African descent” as: “the operation of a complex, interrelated system of laws, policies, practices and attitudes in State institutions, the private sector and societal structures that, combined, result in direct or indirect, intentional or unintentional, de jure or de facto discrimination, distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference on the basis of race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin. Systemic racism often manifests itself in pervasive racial stereotypes, prejudice and bias and is frequently rooted in histories and legacies of enslavement, the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and colonialism.” Rep. of the UN High Comm’r for Hum. Rts., Promotion and protection of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Africans and of people of African descent against excessive use of force and other human rights violations by law enforcement officers, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/47/53, at 1 (Jun. 1, 2021).

[3] Though abortion had been legal up to this point, medically unnecessary regulations and a lack of public funding for abortions meant this care was already limited in many parts of the country, particularly for pregnant people of color. Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, No. 19-1392, 2022 WL 2276808 (U.S. June 24, 2022).

[4] See Oriana Gonzalez & Jacob Knutson, Where abortion has been banned now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, Axios (July 7, 2022), https://www.axios.com/2022/06/25/abortion-illegal-7-states-more-bans-coming.

[5] Katherine Kortsmitt et al., Abortion Surveillance - United States 2019, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: MMWR Surveillance Summaries Vol. 70, No. 9 (2021) [hereinafter Abortion Surveillance], https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/ss/pdfs/ss7009a1-H.pdf (noting that “non-Hispanic White women had the lowest abortion rate (6.6 abortions per 1,000 women) and ratio (117 abortions per 1,000 live births), and non-Hispanic Black women had the highest abortion rate (23.8 abortions per 1,000 women) and ratio (386 abortions per 1,000 live births”); Guttmacher Inst., Characteristics Of U.S. Abortion Patients In 2014 And Changes Since 2008, at 1 (2016), https://perma.cc/9H2V-3VVY (PDF)(demonstrating that earlier data evidence the same trend: “As compared to the population distribution, “thirty-nine percent [of abortion patients] were white, 28% were black, 25% were Hispanic, 6% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3% were of some other race or ethnicity.”).

[6] See Abortion Surveillance.

[7] Lawrence B. Finer et al., Reasons U.S. Women Have Abortions: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives, 37 Persp. on Sexual & Reprod. Health 110, 112, 115 (2005).

[8] Theresa Y. Kim et al., Racial/Ethnic Differences in Unintended Pregnancy: Evidence From a National Sample of U.S. Women, 50 Am. J. Preventative Med., 427-35 (2016).

[9] National Partnership for Women & Families, Despite Significant Gains, Women of Color Have Lower Rates of Health Insurance Than White Women (Apr. 2019), https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/women-of-color-have-lower-rates-of-health-insurance-than-white-women.pdf.

[10] Id.; See also Caitlin Myers et al., Predicted Changes in Abortion Access and Incidence in a Post-Roe World, 100 Contraception 367 (2019) (noting that Black women also disproportionately live in “contraception deserts”—geographic areas with inequitable access to affordable family planning—caused in large part by states only providing public assistance for contraception in urban areas, leaving broad swaths of rural populations with very limited access to affordable family planning).

[11] Asha DuMonthier et al., The Status of Black Women in the United States, Inst. for Women’s Pol’y Rsch., at 66 (2017).

[12] Id.

[13] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Violence Against Native Peoples Fact Sheet (2020) (citing The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Violence Prevention (updated July 19, 2021), https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nisvs/index.html.), https://www.cdc.gov/injury/pdfs/tribal/Violence-Against-Native-Peoples-Fact-Sheet.pdf (estimating that 48% of American Indian and Alaskan Native women will experience physical violence from an intimate partner – a rate that is 30-50% higher than what is experienced by white women); Women of Color Network, Life in the Margins: Expanding Intimate Partner Violence Services for Women of Color by Using Data as Evidence (June 2017), https://vawnet.org/material/life-margins-expanding-intimate-partner-violence-services-women-color-using-data-evidence (showing that “Approximately four out of every ten non-Hispanic Black women . . . have been the victim of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime”).

[14] Brief of Amici Curiae Reproductive Justice Scholars Supporting Respondents [hereinafter “Reproductive Justice Scholars”] at 20, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (No. 1901392), 2022 WL 2276808.

[15] Emily Miller, et al., Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy, 81 Contraception 316-22 (2010); See also Carolyn M. West, Black Women and Intimate Partner Violence: New Directions for Research, 19 J. Interpersonal Violence 1487 (2004) (noting that “racial differences in rates of partner abuse frequently disappear or become less pronounced when economic factors are taken into consideration”).

[16] World Health Organization, Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy Information Sheet (2011), https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70764/WHO_RHR_11.35_eng.pdf; See also Michele Kiely et. al., Understanding the association of biomedical, psychosocial and behavioral risks with adverse pregnancy outcomes among African Americans in Washington, DC. 15 Matern. Child Health J. Suppl. 1 2011; Dina El Kady et. al., Maternal and neonatal outcomes of assaults during pregnancy 105 Obstet. Gynecol. 2 (2005).

[17] Sarah Roberts et al., Risk of violence from the man involved in the pregnancy after receiving or being denied an abortion 12 BMC Medicine 144 (2014), (explaining that women denied an abortion remain tethered to abusive partners and at risk for continued violence, even if they leave the relationship).

[18] Rosalyn Schroeder et. al., Trends in abortion care in the United States, 2017-2021 Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), University of California, San Francisco, 2022 (positing that “[t]he overturning of Roe v. Wade could lead to the eventual closure of 202 facilities across these states, which would shutter 26% of all publicly advertising facilities in the U.S.”).

[19] Many pregnant people living in places with abortion bans will self-managing their own abortions. However, medication abortion is restricted in several states and as this report later details pregnant people risk legal sanction if they end their own pregnancies. See discussion infra para. 16; See also Medication Abortion, Guttmacher Institute (July 1, 2022), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/medication-abortion (showing that separate from blanket abortion bans, two states have passed legislation specifically prohibiting self-induced abortions through the use of abortion medications. Three additional states have attempted such bans on abortion medications, and nineteen others have passed legislation to prohibit abortion telemedicine).

[20] See Brief of Human Rights Watch, Global Justice Center, and Amnesty International as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (No. 1901932), 2022 WL2276808; Margaret Wurth, What Life is Like When Abortion is Banned, Human Rights Watch (June 10, 2019), https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/10/what-life-when-abortion-banned.

[21] Elizabeth Nash & Jonathan Bearak, Abortion Ban: A 14-Fold Increase in Driving Distance to Get an Abortion, Guttmacher Institute (Aug. 4, 2021), https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2021/08/impact-texas-abortion-ban-14-fold-increase-driving-distance-get-abortion.

[22] See Loretta Ross, What is Reproductive Justice?, in Reproductive Justice Briefing Book: A Primer on Reproductive Justice and Social Change 4 (SisterSong ed., 2007); See also, Melissa Murray, Race-ing Roe: Reproductive Justice, Racial Justice, and the Battle for Roe v. Wade, 134 Harv. L. Rev. 2025, 2093 (2021).

[23] See Kaiser Family Foundation, Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity (2019), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D)

[24] Juanita J. Chinn, et al., Health Equity Among Black Women in the United States, 30 J. Women's Health 2 (2021)(noting that “Black women earn on average $5,500 less per year and experience higher unemployment and poverty rates than the U.S. average for women."); Jacqueline C. Wiltshire et al., Disentangling the influence of socioeconomic status on differences between African American and white women in unmet medical needs, 99 Am. J. Pub. Health 9 (2009); Asha DuMonthier et al., supra note 11 at 72 (noting that “nationally, 14.4 percent of Black women aged 25 or older have less than a high school diploma. This rate is about twice as high as the rate for White women (7.5 percent) . . .”).

[25] “For instance, an increase in travel distance from 0 to 100 miles increases births for . . . Black women by 3.3% versus by 2.1% for white women.” Brief of Amici Curiae Economists in Support of Respondents, 21 (2022), https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/193084/20210920175559884_19-1392bsacEconomists.pdf (citing Caitlin Myers, Cooling off or Burdened? The Effects of Mandatory Waiting Periods on Abortions and Births (IZA Inst. Of Lab. Econ., Discussion Paper Series No. 14434, 2021)).

[26] Sixty-seven percent of the “unauthorized immigrant population” in the US was born in Mexico and Central America. An additional eight percent hail from South America, three percent from the Caribbean, fifteen percent from Asia, three percent from Africa, and four percent from Europe/Canada/Oceania. Profile of the Unauthorized Population: United States, Migration Policy Institute (last visited July 12, 2022), https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/US

[27] Immigrants in Texas, American Immigration Council (2020), https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/immigrants_in_texas.pdf.

[28] Stephania Taladrida, The Rio Grande Valley’s Abortion Desert, The New Yorker (Dec. 18, 2021), https://www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-rio-grande-valleys-abortion-desert; See also

Shefali Luthra, After new law, a look inside one of South Texas’ last abortion clinics, The 19th (Sept. 27, 2021), https://19thnews.org/2021/09/new-law-inside-south-texas-abortion-clinic/.

[29] Center for Reproductive Rights, What If Roe Fell?, https://reproductiverights.org/maps/what-if-roe-fell/

[30] Gabriela Bhaskar and Abby Goodnough, Inside One Abortion Clinic, Signs of Nationwide Struggles, N.Y. Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/20/us/politics/abortion-florida-supreme-court.html;

[31] Guttmacher Inst., Parental Involvement in Minors’ Abortions, https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/parental-involvement-minors-abortions

[32] Human Rights Watch, “The Only People It Really Affects Are the People It Hurts”: The Human Rights Consequences of Parental Notice of Abortion in Illinois (Mar. 2021), https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/03/11/only-people-it-really-affects-are-people-it-hurts/human-rights-consequences.

[33] Elizabeth Janiak, et al., Massachusetts’ parental consent law and procedural timing among adolescents undergoing abortion, 133 Obstetrics & Gynecology 5 (2019).

[34] Amanda J. Stevenson, The Pregnancy-Related Mortality Impact of a Total Abortion Ban in the United States: A Research Note on Increased Deaths Due to Remaining Pregnant, 58 Demography 6 (2021).

[35] Working Together to Reduce Black Maternal Mortality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Health Equity (Apr. 6, 2022), https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/maternal-mortality/index.html.

[36] Charlene Collier et al., Mississippi Maternal Mortality Report 2013-2016, Miss. State Dep’t. of Health (Apr. 2019), https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/index.cfm/31,8127,299,pdf/MS_Maternal_Mortality_Report_2019_Final.pdf.

[37] This was also the reality prior to the federal legalization of abortion in 1973. In the decades when illegal abortion was unsafe in the US, the majority of deaths from unsafe abortion were women of color, even though they comprised a minority of the population. See Abortion in the United States: A Conference Sponsored by the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. at Arden House and The New York Academy of Medicine (Ed. Mary Steichen Calderone, New York: Harper and Brothers 1958).

[38] Amy Metcalfe et al., Racial Disparities in comorbidity and severe maternal morbidity/mortality in the United States: an analysis of temporal trends, 97 Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. (2018), 89, 94, (noting that “Black women had both the highest prevalence of preexisting conditions in 1993, as well as the largest increase in prevalence, with 17.3% of Black women having at least one preexisting condition prior to pregnancy in 2008–2012.”).

[39] Id. at 94; See also Elizabeth A. Howell, et al., Black-White Differences in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Site of Care, 214(1) Am. J. Obstetrics Gynecology 1, (2016), 6 (explaining that “both black and white patients who delivered in black-serving hospitals had a higher risk of severe maternal morbidity after accounting for patient characteristics” which “may suggest that quality of care at hospitals that disproportionately serve blacks is lower than quality at low black-serving hospitals.”).

[40] Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: COVID-19 (updated Jul. 24, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html.

[41] One recent study on the effects of abortion access on Black women’s participation in the workforce indicated an increase in participation by 6.9 percentage points. (Anna Bernstein, MPH & Kelly M. Jones, PhD, The Economic Effects of Abortion Access: A Review of the Evidence, Institute for Women’s Policy Research Center on the Economics of Reproductive Health (2020), https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/B379_Abortion-Access_rfinal.pdf). See also, Amy Roeder, The negative health implications of restricting abortion access, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Dec. 13, 2021), https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/abortion-restrictions-health-implications/.

[42] Data from the US reveals the financial effects of being denied an abortion are as large or larger than those of being evicted, losing health insurance, being hospitalized, or being exposed to flooding due to a hurricane. See Diana Greene Foster et al., Socioeconomic Outcomes of Women Who Did and Did Not Terminate Pregnancy After Seeking Abortion Services, 171 Annals Internal Med. 238 (2019). See also, Brief of Amici Curiae Economists in Support of Respondents at 24, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (No. 1901392) 2022 WL2276808, (citing Sarah Miller et al., The Economic Consequences of Being Denied an Abortion, Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 26662 (2020)).

[43]See Kaiser Family Foundation, Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity (2019), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D)

[44] Asha DuMonthier et al., supra note 11(noting that Currently, Black women comprise a majority of women working in the service industry and in care-taking roles that often have lower pay and fewer benefits).

[45] Unemployment rates for Black women are higher than those for any other racial group – in 2021, the unemployment rate for Black women was 9.2% while white women were unemployed at a rate of just 5.4%. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey (Jul. 8, 2022), https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpsee_e16.htm.

[46] Asha DuMonthier et al., supra note 11 (explaining that Black women are underrepresented in management and professional roles and face discrimination in the labor market.).

[47] See Alison Durkee, Performing an Abortion Will Become a Felony in These States if Roe v. Wade is Overturned, Forbes (May 4, 2022) [hereinafter Abortion Will Become a Felony], https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2022/05/04/performing-an-abortion-will-become-a-felony-in-these-states-if-roe-v-wade-is-overturned/?sh=bac1e949f5bc (showing that Texas, Louisiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, South Carolina, Arkansas, Idaho, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Alabama all have criminal penalties for obtaining or performing an abortion. Wyoming also has a pre-Roe ban that could possibly criminalize abortion, but the penalty is not specified.).

[48] Rachel Berquist et al., State Funded Housing Assistance Programs, Technical Assistance Collaborative (Apr. 2014) at 8, https://www.tacinc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/State-Funded-Housing-Assistance-Report.pdf (explaining that South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and South Dakota had no state-run programs to meet the housing needs of low-income residents).

[49] Lauren Hall & Catlyn Nichako, A Closer Look at Who Benefits From SNAP: State-By-State Fact Sheets, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (updated Apr. 25, 2022), https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-closer-look-at-who-benefits-from-snap-state-by-state-fact-sheets#Alabama (explaining that In Alabama, Tennessee, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Arkansas, South Dakota, Mississippi, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Texas, at least 19% of children live below the poverty line).

[50] Brief of Amici Curiae Economists in Support of Respondents, supra note 42, at 21, (citing Child Care and Development Fund Program, 81 Fed. Reg. 67440 (2016)).

[51] U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Promotion and protection of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Africans and of people of African descent against excessive use of force and other human rights violations by law enforcement officers, at ¶ 25, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/47/53 (Jun. 1, 2021); See also Carrie Johnson, Flaws plague a tool meant to help low-risk federal prisoners win early release, NPR (Jan. 26, 2021), https://www.npr.org/2022/01/26/1075509175/justice-department-algorithm-first-step-act (referencing First Step Act Annual Report: April 2022, US Dept. of Justice, Office of the Attorney General (Apr. 2022), https://www.ojp.gov/first-step-act-annual-report-april-2022)(explaining that the US Department of Justice found its own risk assessment tool “PATTERN” overestimates the number of Black women who will engage in recidivism, despite repeated attempts to eliminate racial bias from the tool.); See also Carrie Johnson, Justice Department works to curb racial bias in deciding who's released from prison, NPR (Apr. 19, 2022), https://www.npr.org/2022/04/19/1093538706/justice-department-works-to-curb-racial-bias-in-deciding-whos-released-from-pris.

[52] National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Abortion in America: How Legislative Overreach Is Turning Reproductive Rights Into Criminal Wrongs (2021), https://www.nacdl.org/Document/AbortioninAmericaLegOverreachCriminalizReproRights (reporting that over 4,450 crimes in the federal criminal code and tens of thousands of state criminal laws exist that could subject a wide range of individuals to criminal penalties when the constitutional right to abortion is overturned).

[53] See Sarah Mervosh, Alabama Woman Who Was Shot While Pregnant Is Charged in Fetus’s Death, N.Y. Times (June 27, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/27/us/pregnant-woman-shot-marshae-jones.html.

[54] See Iowa Police Almost Prosecute Woman for Her Accidental Fall During Pregnancy . . . Seriously., ACLU Me. (Feb. 11, 2010, 5:04 PM), https://www.aclumaine.org/en/news/iowa-police-almost-prosecute-woman-her-accidental-fall-during-pregnancyseriously [https://perma.cc/WMB9-YTKT].

[55] Jessica Mason Pieklo, Legal Wrap: Finally Some Justice for Bei Bei Shuai, Rewire News Grp. (Aug. 6, 2013), https://rewire.news/article/2013/08/06/legal-wrap-finally-some-justice-for-bei-bei-shuai/.

[56] National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, supra note 52; See also National Advocates for Pregnant Women et al., Submission to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review of the United States of America: Criminalization & Civil Punishment of Pregnancy and Pregnancy Outcomes (May 2020), https://www.nationaladvocatesforpregnantwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/UPR-Crim-report.pdf.

[57] People v. Perez, No. F077851, 2019 WL 1349709 (Cal. Ct. App. Mar. 26, 2019).

[58] See Application to File [Proposed] Amicus Curiae Brief In Support of Petitioner Adora Perez at 14, People v. Perez, No. F077851, 2019 WL 1349709 (Cal. Ct. App. Mar. 26, 2019), https://www.nationaladvocatesforpregnantwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Perez-Brief-Filed.pdf.

[59] Id.

[60] Ruling Granting Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, People v. Perez, No. F077851, 2019 WL 1349707, https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/attachments/press-docs/2022-3-16%20order%20granting%20habeas.pdf.

[61] National Advocates for Pregnant Women, Arrests and Deprivations of Liberty of Pregnant Women, 1973-2020 (Sept. 2021), bit.ly/arrests1973to2020.

[62] See Amnesty International, Criminalizing Pregnancy: Policing Pregnant Women Who Use Drugs in the USA at 23 (Sept. 23, 2017), https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr51/6203/2017/en/ [hereinafter Amnesty International, Criminalizing Pregnancy]; See also, Michelle Goodwin, Policing The Womb: Invisible Women And The Criminalization Of Motherhood (2020), 109-110; Aziza Ahmed, Floating Lungs: Forensic Science in Self-Induced Abortion Prosecutions, 100 B.U. L. Rev. (2020), 1111, 1116, 1121, 1124; Cortney E. Lollar, Criminalizing Pregnancy, 92 Ind. L.J. (2017) 947, 949, 998.

[63] Amnesty International, Criminalizing Pregnancy supra note 62.

[64] These prosecutions and the threat of such prosecutions infringe on pregnant people of color’s right to health because they deter women from accessing health care for fear of criminal sanction. This includes prenatal care, treatment for substance misuse, and care during a miscarriage. For pregnant people suffering from substance abuse, remarkably, the state is responding with prosecution rather than social services and health care. Amnesty International, Criminalizing Pregnancy supra note 62 at 23.

[65] Incarcerated Women and Girls, The Sentencing Project (Nov. 24, 2020), https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/incarcerated-women-and-girls/.

[66] National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, supra note 52.

[67] Emily M. Morgenstern and Nick M. Brown, Foreign Assistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy, Cong. Res. Service (Updated Jan. 10, 2022), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R40213.

[68] Following the 1973 US Supreme Court’s recognition of a constitutional right to abortion in Roe v. Wade, the anti-abortion movement used the Helms Amendment to assert its power and control over a different population, one outside of the US. See Lienna Feleke-Eshete, This Racist Policy Contributes To The Death Of Thousands Of Black And Brown Women And Girls, And You’ve Probably Never Heard Of It, Blavity (Oct. 8, 2020), https://blavity.com/this-racist-policy-contributes-to-the-death-of-thousands-of-black-and-brown-women-and-girls-and-youve-probably-never-heard-of-it?category1=opinion&category2=politics.); The Amendment is named for the late Senator Jesse Helms, whose racist, homophobic, and misogynist views were widely known, and which underpin the policy. Michelle Goodwin, It’s Time to Confront Senator Helms’s Sexist, Racist and Homophobic Legacy, Ms. Mag. (Aug. 13, 2020), https://msmagazine.com/2020/08/13/helms-amendment-its-time-to-confront-senator-jesse-helms-sexist-racist-and-homophobic-legacy/.

[69] Population Institute, The Time is Now: Repeal the Helms Amendment (Mar. 2021), https://www.populationinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/PI-3050-Helms-Brief.pdf; See also World Health Organization, Abortion (Nov. 2021), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preventing-unsafe-abortion; See also Susan A. Cohen, Access to Safe Abortion in the Developing World: Saving Lives While Advancing Rights, 15 Guttmacher Pol. Rev. 3 (2012).

[70] Id.

[71] Kellie Moss & Jennifer Kates, The Helms Amendment and Abortion Laws in Countries Receiving U.S. Global Health Assistance, Kaiser Family Foundation (Jan. 18, 2022), https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/the-helms-amendment-and-abortion-laws-in-countries-receiving-u-s-global-health-assistance/.

[72] Id.

[73] Ipas & Ibis Reproductive Health, U.S. Funding for Abortion: How the Helms and Hyde Amendments Harm Women and Providers 14 (2015), https://www.ibisreproductivehealth.org/sites/default/files/files/publications/Ibis%20Ipas%20Helms%20Hyde%20Report%202016.pdf.

[74] Michelle Onello & Elena Sarver, The Fight to Secure U.S. Abortion Rights Is Global, Ms. Mag. (May 24, 2022), https://msmagazine.com/2022/05/24/us-foreign-policy-abortion-helms-amendment-global-gag-rule/.

[75] Helms Amendment Hurts Millions of People Worldwide, Planned Parenthood Action Fund (June 1, 2022), https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/communities/planned-parenthood-global/helms-amendment-hurts-millions-people-worldwide.

[76] Ipas & Ibis Reproductive Health supra note 73, at 9.

[77] The Helms Amendment prohibits the use of US foreign assistance funds for abortion as a “method of family planning.” This does not include all abortions. Abortion care in cases of rape, incest, and life endangerment are not “methods of family planning” and as such can be provided using US funding. However, in practice the Helms Amendment is applied as a total ban on abortion services and speech. Adva Saldinger, Bracing for global impact as Roe v. Wade abortion decision overturned, Devex (June 24, 2022), https://www.devex.com/news/bracing-for-global-impact-as-roe-v-wade-abortion-decision-overturned-103464.

[78] Only a subset of state obligations under ICERD are limited such as the Article 3 obligation concerning racial segregation and apartheid, which explicitly applies to parties with respect to “territories under their jurisdiction”. Similarly, the Article 6 provision of remedies operates with respect to people in the state’s “jurisdiction.” See International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination [hereinafter ICERD], 660 U.N.T.S. 195, (Dec. 1965). The International Court of Justice’s 2008 order for provisional measures in the case of Georgia v. Russian Federation also clarifies that ICERD applies extraterritorially. Specifically, the Court held that the ICERD provisions at issue (in particular, Articles 2 and 5) “appear to apply” extraterritorially because there is no express restriction on territorial application in relation to either the treaty generally or the provisions that were at issue. Application of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Georgia v. Russian Federation), Request for the Indication of Provisional Measures, 2008 I.C.J. 353, ¶ 109 (Oct. 2008).

[79] Emily Widra and Tiana Herring, States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021, Prison Policy Initiative (Sept. 2021), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2021.html

[80] See Ashley Nellis, The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons, The Sentencing Project (Oct. 13, 2021), https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/ (showing that Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons at nearly five times the rate of white Americans.).

[81]Bonnie Sultan and Mark Myrent, Women and Girls in Corrections, Justice Research and Statistics Association (Nov. 2020), https://www.jrsa.org/pubs/factsheets/jrsa-factsheet-women-girls-in-corrections.pdf.

[82] The Sentencing Project supra note 65.

[83] Id.

[84] Leah Wang, The U.S. criminal justice system disproportionately hurts Native people: the data, visualized, Prison Policy Initiative (Oct. 8, 2021), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/10/08/indigenouspeoplesday/.

[85] Eileen Sullivan, Biden Will End Detention for Most Pregnant and Postpartum Undocumented Immigrants, N.Y. Times (Oct. 27, 2021) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/09/us/politics/pregnant-postpartum-immigration-biden.html.

[86] See Comm. Against Torture, Conclusions and recommendations of the Comm. Against Torture, U.N. Doc. CAT/C/USA/CO/2 (2006); Comm. Against Torture, Concluding observations on the combined third to fifth periodic reports of the US, U.N. Doc. CAT/C/USA/CO/3-5 (2014); Rep. of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/31/57 (2016); Human Rights Comm., List of issues prior to submission of the fifth periodic report of the US, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/USA/QPR/5 (2019); Conc. Observations of the Human Rights Comm., U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/USA/CO/3/Rev.1 (2006).

[87] Victoria Law, Formerly Incarcerated Women in Tennessee Win Reforms Ending Shackled Births, TruthOut (Jun. 26, 2022), https://truthout.org/articles/formerly-incarcerated-women-in-tennessee-win-reforms-ending-shackled-births/.

[88] Lorie S. Goshin et. al., Perinatal Nurses’ Experiences With and Knowledge of the Care of Incarcerated Women During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period, 48 J. Obstet., Gynecol., & Neonatal Nursing 1 (2019).

[89] Priscilla A. Ocen, Punishing Pregnancy: Race, Incarceration, and the Shackling of Pregnant Prisoners, 100 Calif. L. Rev. 5 (2012).

[90] Id at 1244.

[91] Alexs Kajstura, Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019, Prison Policy Initiative (October 29, 2019). https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2019women.html; See also American Civil Liberties Union, Briefing Paper: The Shackling of Pregnant Women & Girls in U.S. Prisons, Jails & Youth Detention Centers, https://www.aclu.org/files/assets/anti-shackling_briefing_paper_stand_alone.pdf.

[92] Goshin et. al., supra note 90.

[93] Alison Smock, Childbirth in Chains: A Report on the Cruel but not so Unusual Practice of Shackling Incarcerated Pregnant Females in the United States, 3 Tenn. J. of Race, Gender, & Social Justice (2014).

[94] Comm. On Health Care for Underserved Women, Reproductive Health Care for Incarcerated Pregnant, Postpartum, and Nonpregnant Individuals, Am. College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Comm. Opinion 830 (July 2021), https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2021/07/reproductive-health-care-for-incarcerated-pregnant-postpartum-and-nonpregnant-individuals.

[95] American Medical Association, Policy H-420.957 on Shackling of Pregnant Women in Labor (2020), https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/shackling?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-3700.xml

[96] American Psychological Association Public Interest Government Relations Office, End the Use of Restraints on Incarcerated Women and Adolescents During Pregnancy, Labor, Childbirth and Recovery (Aug. 2017), https://www.apa.org/advocacy/criminal-justice/shackling-incarcerated-women.pdf

[97] Nelson v. Correctional Medical Services, 533 F.3d 958 (5th Cir. 2008).

[98] Brawley v. Washington, 712 F. Supp. 2d 1208 (W.D.W.A. 2010).

[99] UN Standard Minimum Rules for Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules) Rule 48 G.A. Res. 70/175 (2016); UN Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the Bangkok Rules) Rule 24 G.A. Res. 65/229 (2011).

[100] Comm. Against Torture supra note 86 at ¶21(j); See also Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment supra note 86 at ¶21, 69(h.

[101] The Sentencing Project supra note 65.

[102] Wendy Sawyer and Wanda Bertram, Prisons and jails will separate millions of mothers from their children in 2022 n.2, The Sentencing Project (May 4, 2022), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2022/05/04/mothers_day/.

[103] Comm. on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Concluding Observations of on the combined seventh to ninth periodic reports of the United States, of America Geneva, U.N. Doc. CERD/C/USA/CO 7-9 (2014).

[104] American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures for African Americans, 2019-2021 at 3 (2019), https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2019-2021.pdf.

[105] Rep. of the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights on his mission to the United States of America, at ¶57, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/38/33/add.1 (2018).

[106] American Cancer Society, Key Statistics for Cervical Cancer (updated Jan. 12, 2022), https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

[107] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Maternal Mortality, https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/index.html (last visited June 22, 2022).