Summary

Cervical cancer is not a disease that anyone should die from. It just doesn't make any sense. We know too much about it for it to be something that people die from.

—Dr. Favors, obstetrician gynecologist in Albany, Georgia, June 6, 2021

Cervical cancer is highly preventable and treatable. It typically develops over several years, providing ample time to detect and treat abnormal changes in cervical cells that could eventually lead to cancer. With access to information, preventive services, and routine gynecological care, most cases of the disease can be prevented and successfully treated at an early stage. If caught early before cancer has spread, the five-year survival rate is over 90 percent. Despite this, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimated that 4,290 women would die of cervical cancer in the United States in 2021.

Although almost no one should die from the disease, some groups—those that are historically marginalized and neglected in the US, including women of color, women living in poverty, and those without health insurance—die more often than others. There are glaring racial disparities in cervical cancer deaths in the US and Black women die of the disease at a disproportionately high rate. Black women have a higher risk of late-stage diagnosis, and they are more likely to die from the disease than any other racial or ethnic group in the country. In the state of Georgia, Black women are almost one and a half times as likely to die of cervical cancer as white women and these disparities increase at alarming rates as they age. Black Georgian women are more likely to have never been screened for cervical cancer, are diagnosed at a later stage, and have lower five-year survival rates.

Preventable deaths from cervical cancer thrive in contexts of structural racism, discrimination, poverty, and inequality. Disparities in cervical cancer for Black women and other marginalized and neglected individuals reflect exclusion from the healthcare system and unequal access to the information, interventions, and services necessary to prevent and treat the disease. These preventable deaths also represent a failure of the federal, state, and local governments to protect and promote human rights for all people and to ensure adequate and affordable access to the lifesaving reproductive healthcare services and information all people need and have a right to.

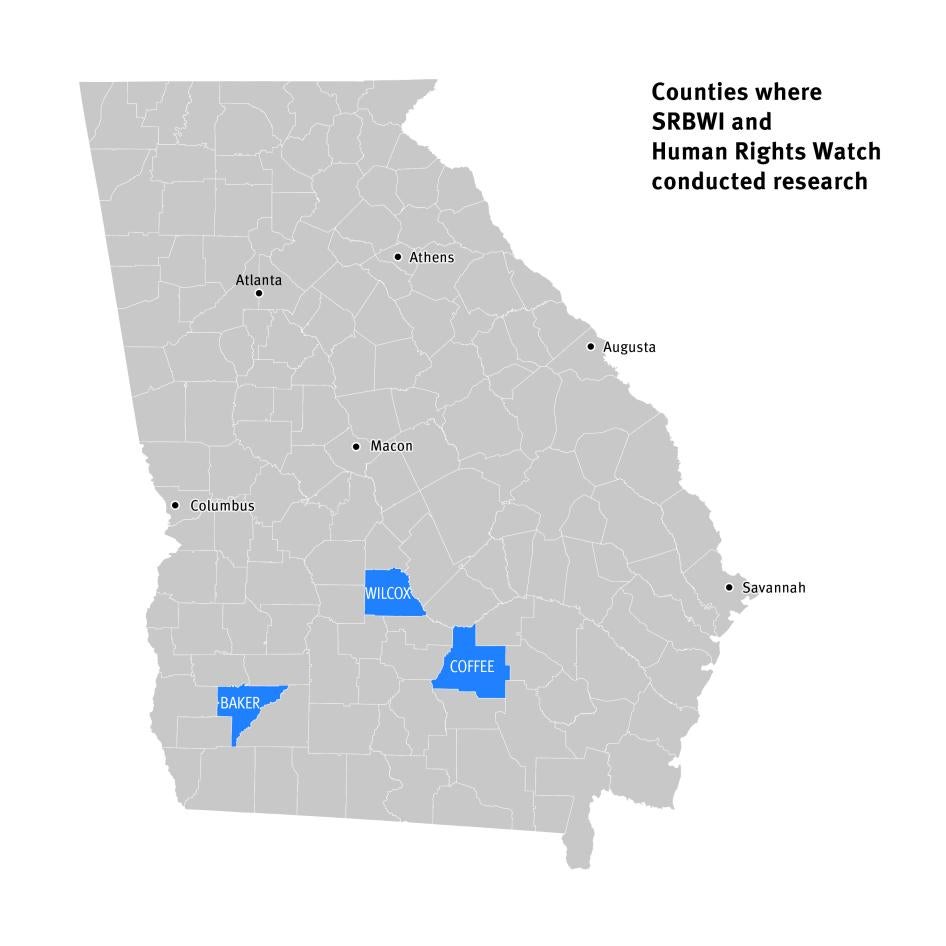

Between November 2020 and August 2021, the Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative for Economic and Social Justice (SRBWI) and Human Rights Watch partnered with nine community-based researchers to document factors contributing to disproportionate cervical cancer death rates for Black women in Georgia. Community-based researchers carried out 148 interviews with Black women between the ages of 18 and 82 living primarily in 3 counties—Baker, Coffee, and Wilcox—in rural southwest Georgia. The women described the challenges they face in accessing reproductive healthcare services and information to prevent and treat cervical cancer. SRBWI and Human Rights Watch also spoke with community members, academics, medical providers, public health officials, and members of nongovernmental health and reproductive rights and justice groups in Georgia to better understand cervical cancer prevention and care, and barriers to adequate health care in the state.

This research found that Georgia state and local agencies, and the US federal government are not doing enough to facilitate access to reproductive healthcare services and information to prevent cervical cancer deaths and address racial disparities in health outcomes. Georgia does not ensure access to comprehensive and affordable reproductive health care, and instead relies on a patchwork of multiple, publicly funded programs to extend healthcare coverage to low-income women in the state, including for gynecological care. Georgia has not expanded Medicaid through the US Affordable Care Act (ACA) to extend healthcare coverage to more low-income individuals, for which the state is losing out on $3 billion in federal funding each year. Over 255,000 Georgians have no options for affordable healthcare coverage. Without a comprehensive plan to guarantee access to consistent and affordable health care, the state has left low-income and uninsured Georgian women—who are more likely to be Black—struggling to navigate gaps in health insurance coverage and enormous financial barriers to cervical cancer care. For many women, especially those who are uninsured, their inability to afford reproductive healthcare services means that they often avoid medical appointments and skip cancer screenings and follow-up care altogether, forgoing lifesaving opportunities to prevent and treat the disease.

Limited access to gynecological care also creates barriers to cervical cancer care for marginalized women, especially those living in rural and underserved areas. Georgia faces a severe shortage of obstetrician gynecologists and almost half of the state’s 159 counties do not have one. State policies have contributed to the closure of rural hospitals, which has helped fuel this shortage. Since 2010, 7 rural hospitals have closed in Georgia and 38 labor and delivery units have shut down since 1994, leaving entire communities without access to essential pregnancy and gynecological services. Georgia could increase healthcare coverage for more low-income people in the state, decreasing the cost of uncompensated care and providing a financial lifeline for hospitals struggling to stay afloat, especially in rural areas, by expanding Medicaid. Its decision not to do so has contributed to a shortage of obstetrical and gynecological care in rural areas.

The Georgia government’s failure to provide adequate public transportation throughout the state, especially in rural counties, creates additional challenges to obtaining cervical cancer care. For women who have to travel long distances for gynecological care and for those who lack adequate transportation, including money for gas or to pay someone to take them to appointments, accessing cervical cancer care is often burdensome, costly, and, at times, even impossible.

Structural racism and discrimination in the healthcare field, coupled with many Black women’s related distrust of medical providers, also impacts the quality of care some women receive and their willingness to seek out reproductive health care. SRBWI and Human Rights Watch spoke with women who said they felt that their health concerns were dismissed and the quality of care they received was inadequate because of racism and medical providers’ bias against them as Black women. Many others described how callous treatment, an inadequate level of care, and concerns around confidentiality have undermined the trust they have in doctors, alienated them from gynecological care, and contributed to poor reproductive health outcomes.

Georgia state policies do not facilitate widespread access to lifesaving information to prevent and treat cervical cancer. Georgia’s government has not adopted adequate policies to ensure that all residents have access to accurate and comprehensive information on the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine—an effective cancer prevention tool. HPV Cancer Free Georgia—the Georgia Cancer Control Consortium (GC3) working group that focuses on implementing the Georgia Cancer Control Plan’s HPV objectives— along with numerous organizations and some state legislators, has tried to fill this gap, for example, by increasing education around HPV, the vaccine, and HPV-related cancers through strategic engagement and outreach and working together in recognition of cervical cancer and HPV awareness days. Many Georgian residents, including about a third of the women that SRBWI and Human Rights Watch interviewed, lack information on the HPV vaccine, and vaccination rates in the state are below the national average. At the same time, the government is failing to ensure that all young people in schools receive comprehensive, inclusive, and accurate information on their sexual and reproductive health. Inadequate access to this lifesaving information undermines Georgian women and girls’ understanding of cervical cancer and the preventive steps people can take to lower risk and stay healthy and safe. It also contributes to misinformation, fear, and stigma around sexual and reproductive health that makes many women reluctant to discuss or seek out cervical cancer care.

The Covid-19 pandemic has created new obstacles to accessing preventive health care and disrupted cervical cancer care, which could widen racial health disparities. HPV vaccination rates and cervical cancer screenings—both essential aspects of cervical cancer prevention—dropped dramatically at the start of the pandemic in March 2020. Vaccination and screening rates started to increase in June 2020 as stay-at-home orders and restrictions eased. However, these delays and disruptions in preventive care may contribute to poor cervical cancer outcomes and an increase in preventable deaths from cancer over the long term, with the greatest impact on marginalized individuals and those who already faced multiple barriers to accessing adequate and affordable health care. While the dramatic rise in telehealth services in response to the pandemic has the potential to expand access to medical care, it has also underscored the need to ensure that these services adequately address existing broadband and technology inequalities and promote equal access to affordable and quality health care for everyone.

The Georgia state and the US federal governments have allowed substantial barriers to cervical cancer care for marginalized women to become embedded and have failed to protect and promote Georgian women and girls’ rights under international human rights law to health, information, equality, and nondiscrimination. The state government should invest in policies and programs that address persistent racial and socioeconomic inequalities in access to health care and take concrete steps to reduce racial disparities in cervical cancer outcomes by expanding Medicaid to increase affordable healthcare coverage for more low-income Georgians; enacting policies to ensure affordable and accessible cervical cancer care for all women, including those in rural and underserved communities; and adopting legislation to support comprehensive sexual health education in all Georgia schools.

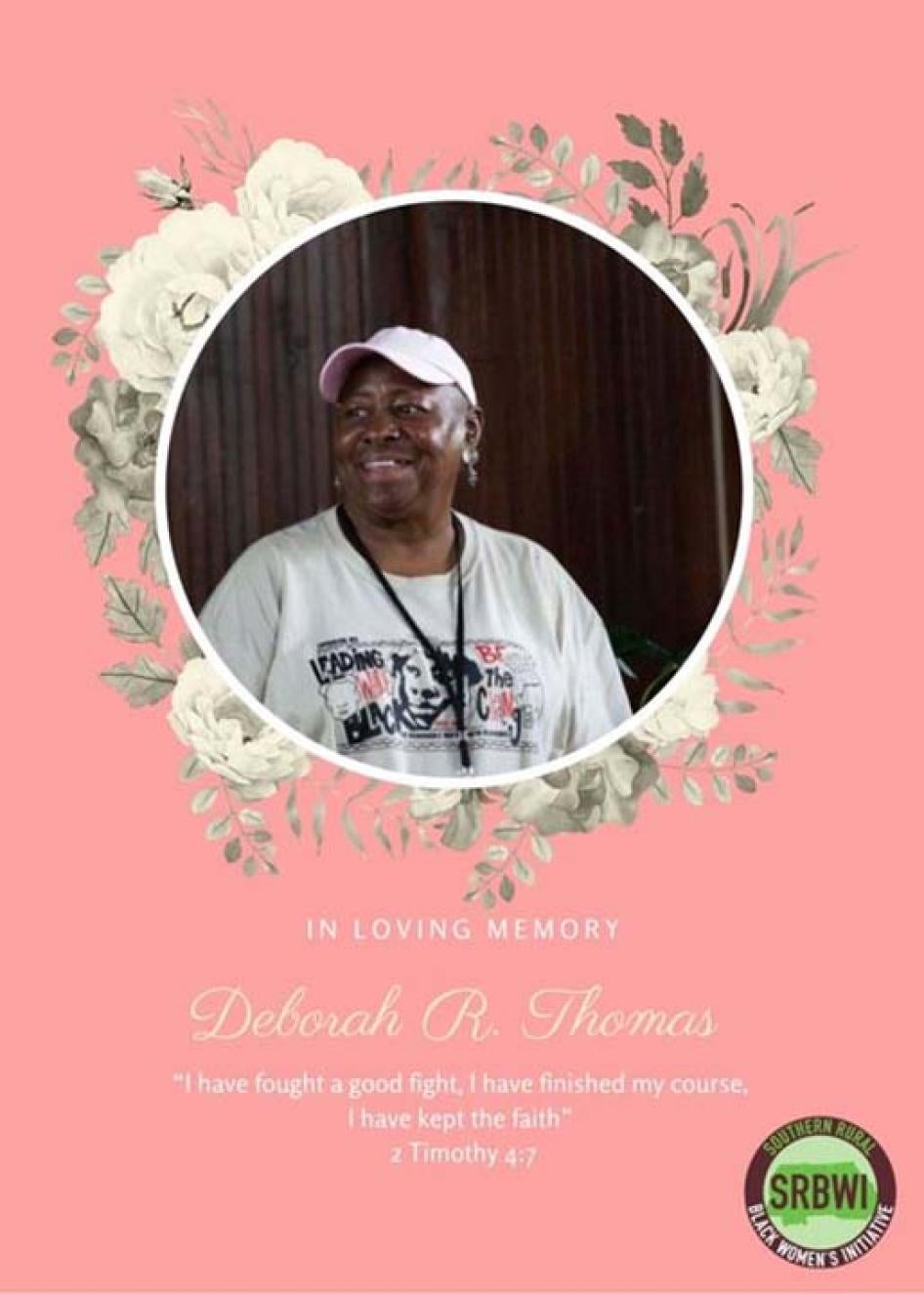

In Memoriam: Deborah Ann Thomas

Often when we read statistics such as cervical cancer unnecessarily claimed the lives of an estimated 4,290 women in the United States in 2021, our tendency is to calculate the loss as compared to losses resulting from other causes, failing to grasp completely the gravity of the fact that these numbers represent actual lives.

This report is dedicated to the life of Deborah Ann Thomas, who served as co-coordinator of participatory, community-based research for the Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative on this project and whose life was taken by cancer only a few months before the report’s release.

The loss of Deborah is a staggering reminder of the value of one life and its reverberating resonance with the multitude of lives that one life touches, shapes, and, at its utmost, embraces, inspires, and motivates. Like the rising sun, Deborah consistently brought into view the subtle magnificence that surrounds us and which is within each of us—rooted in her unrelenting recognition that everyone and everything is of consequence. This ability to see and uplift the human spirit and to innately see and know what was needed is, as they say, how Deborah rolled, every day, and in everything she did. The knowledge that every life counts was the quiet strength behind her fight and one of the many earnest lessons she left with family members, friends, colleagues, and with the children, women, and families she served who had the fortune of experiencing her grace.

This report is dedicated to Deborah’s resolute commitment to the value of a life, and by extension, to uplifting the human right to quality, accessible, reproductive health care, and removing barriers to access. Our charge to continue the fight to eradicate cervical cancer deaths, which impacts one and a half times as many Black women as white and who are more likely to die from the disease each year, is our promise to Deborah to continue this charge with the integrity that she infused in it and with the sobering awareness that one life lost unnecessarily is one too many.

Recommendations

To the Georgia State Government

To the Governor of Georgia

- Support the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to increase affordable access to healthcare services for Georgian residents.

- Withdraw the Section 1115 Demonstration proposal, including the imposition of work requirements for Medicaid eligibility, and expand coverage to all low-income adults through Medicaid (as intended under the ACA).

- Develop and implement a comprehensive, rights-respecting plan to eliminate cervical cancer deaths in Georgia and obtain funding support from the state legislature.

To the Georgia State Legislature

- Pass legislation to expand Medicaid under the ACA to increase access to healthcare services for the residents of Georgia.

- Appropriate funds for cervical cancer prevention, treatment, and maintenance care, including increased funding for the Georgia Breast and Cervical Cancer Program.

- Enact legislation to support awareness of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and to increase HPV vaccination rates in Georgia. Legislation should:

- disseminate information on Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)-recommended adolescent vaccines to the parents or guardians of all students in Georgia completing the 5th grade;

- require education around HPV and prevention of HPV-related cancers for all students starting in 6th grade; and

- allocate funding to community-based organizations for public awareness and outreach campaigns around HPV, the HPV vaccine, and the prevention of HPV-related cancers.

- Develop and fund a plan to address high cervical cancer mortality rates disproportionately impacting older Black women in Georgia, including a review of current cervical cancer screening guidelines to ensure that they do not lead to inequitable outcomes on the basis of age or race.

- Support community health outreach programs and legislation to establish a formal community health worker certification program in Georgia.

- In collaboration with communities and community-based development and advocacy organizations and agencies, develop and fund initiatives and programs to address barriers to accessing healthcare services linked to the unavailability of public transportation.

- Institute and expand incentives for obstetrician gynecologists to practice in rural, underserved communities in Georgia.

- Adopt measures to expand accessible and affordable telehealth services in rural areas.

- Repeal funding for crisis pregnancy centers, and mandate that all women’s health funding is appropriated to healthcare providers that offer scientifically based, comprehensive, and preventive reproductive health services.

- Adopt legislation and appropriate funds to support comprehensive sexual health education in all Georgia schools. Sexual health education should be age-appropriate, scientifically and medically accurate, and responsive to the needs of all young people.

- Expand the vaccine protocol to allow pharmacists to administer the HPV vaccine without a prescription in accordance with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) standard immunization schedule.

To State Agencies, including the Georgia Department of Public Health and the Georgia Department of Education

- Ensure reproductive health and cervical cancer resources are available and accessible in areas of the state where there is little access to reproductive health care.

- In full collaboration with local communities, conduct a public awareness campaign to inform Georgians of:

- services offered by county health departments and state programs;

- cervical cancer prevention and care, including how to access services that can help reduce cervical cancer risk; and

- the importance of catching up on cervical cancer screenings and HPV vaccinations that may have been delayed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Develop and implement programs to ensure affordable and accessible cervical cancer follow-up care, including colposcopies, in rural and underserved communities.

- Ensure medical providers and women over 50 have access to information on the importance of adequate screening leading up to age 65 and the need for continued screening for women at high-risk or with irregular or undetermined screening histories.

- Support community health workers and community-based approaches to reproductive health care that address healthcare access and the social determinants of health.

- Partner with local communities, groups, and organizations to implement community-based initiatives to educate young people, including those who are out of school, on healthy sexual behaviors and to address stigma around sexual health.

- Increase targeted outreach, awareness-raising, and provider trainings to ensure high coverage for the HPV vaccine as an effective cancer prevention tool.

- Establish inclusivity policies that:

- support linguistic and racial diversity, including in county public health departments; and

- acknowledge, confront, and seek to remedy historic and current experiences of racial discrimination in public health.

- Provide cultural competency, implicit bias, and anti-racism training to address the ways in which structural racism manifests within the healthcare field and impacts the treatment and quality of care patients receive.

- Create an official, confidential, and accessible complaint mechanism for patients who use public health departments; widely disseminate information on the complaint mechanism, including how to use it, aggregate data on complaints received, and remedies implemented.

- Develop and circulate a model curriculum on sexual health education based on best practices and national and international sexual health education standards for all schools to follow that is comprehensive, medically and scientifically accurate, and inclusive of all students.

- Create and implement methods for tracking the content of sexual health education curriculum of all Georgia schools, requiring annual reporting to the Georgia Department of Education.

- Disseminate information on HPV, the HPV vaccine, and the prevention of HPV-related cancers to parents and guardians.

- Conduct outreach to inform parents and guardians of the importance of catching up on wellness visits and adolescent vaccinations that may have been delayed or skipped due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

To the United States Government

To the President

- Adopt policies to support full Medicaid expansion under the ACA to all 50 US states.

- Establish the White House Office of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Wellbeing (OSRHW), under the Domestic Policy Council, to promote sexual and reproductive health and well-being through a human rights, reproductive justice, and racial equity framework.

To Congress

- Pass legislation aimed at addressing high rates of preventable cervical cancer deaths, including racial disparities in mortality rates.

- Enact the

- Expand the options for states to extend Medicaid eligibility, per the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000, to provide for maintenance care and continued surveillance for women who have been successfully treated for breast or cervical cancer.

- Reinstate and appropriately fund the Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection and Control Advisory Committee.

- Support Medicaid expansion into all states as an important measure for addressing preventable gynecological cancer deaths.

- Enact the Medicaid Saves Lives Act to create a federal Medicaid-style program to expand affordable healthcare coverage to low-income individuals in the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid.

- Fund a study and demonstration project on barriers to transportation impacting the ability of low-income women, particularly women of color, in rural areas to travel to appointments for cervical cancer screenings and follow-up care.

- Stop funding abstinence-only education grants and ensure adequate funding for scientifically and medically accurate comprehensive sexual health education programs.

- Adopt the Real Education for Healthy Youth Act, or similar legislation, to support comprehensive sexual health education and restrict funding to health education programs that are medically inaccurate or unresponsive to the needs of all students.

- The Senate should ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

To Federal Agencies, including the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services

- Reject Georgia’s Section 1115 Demonstration proposal, which would institute work requirements for Medicaid eligibility.

- Recommend that colposcopy, diagnostic testing for cervical cancer and precancerous lesions, and early interventions like excisional and ablative treatments, all of which help in the prevention of cervical cancer, be included as preventive care under the ACA’s essential health benefits mandate.

- Review and adjust the current methodology for cervical cancer data analysis to ensure that it reflects the true rates of cervical cancer incidence and mortality. The review should consider whether including women with hysterectomies in the at-risk population artificially lowers reporting on racial disparities in cervical cancer rates.

- Publicize a strategic plan with clear benchmarks for how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will operationalize its recent commitment to fund health programs that address health inequities rooted in racism. In particular, direct more allocated funding into support for community-based projects including the Social Determinants of Health Accelerator Plans and Social Determinants of Health Community Pilots and regularly report on outcomes of funded projects.

- Guide states to ensure National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) funds support community-based healthcare workers serving Black women.

- Target funds allocated for the CDC’s Community Approaches to Reducing STDs project under the Division of STD Prevention’s Health Equity initiative to support programming to remove barriers to accessing the HPV vaccine for rural Black women and youth.

To the United Nations

To the United Nations Committees on Human Rights and the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

- Call upon the US to comply with its international obligations to eliminate disparate racial impacts in public health, including racial disparities in cervical cancer outcomes.

- Call upon the US to improve oversight, establish incentives, and take other necessary steps to ensure compliance with human rights obligations at the state and local levels.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted jointly by the Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative for Economic and Social Justice (SRBWI) and Human Rights Watch in November and December 2020 and January through August 2021.[1] Nine community-based researchers conducted most of the qualitative interviews for this report. Two Human Rights Watch researchers and two SRBWI participatory research consultants developed the research design, facilitated researcher training, and conducted additional interviews and research analysis throughout the duration of the project.

This report is based on individual interviews conducted with Black women in Georgia between November 2020 and February 2021 and follow-up interviews that took place between June and August 2021. Interviews were concentrated in three counties in southwest Georgia—Baker, Coffee, and Wilcox—with additional interviews with women in surrounding Clay, Crisp, Dougherty, Randolph, Mitchell, and Telfair counties. One interviewee currently living in Fulton County shared her experiences growing up in Wilcox County.

Research was conducted in the southwest region of the state to document the specific barriers that Black women living in predominantly rural communities in Georgia face in accessing reproductive healthcare services and information. Specifically, Baker, Coffee, and Wilcox counties were chosen because SRBWI has Human Rights Commissions in those counties headed by human rights commissioners who are actively engaged in local and regional advocacy and community-based initiatives.

Individual interviews were conducted with 148 people, mostly Black women between the ages of 18 and 82. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, all interviews were conducted virtually via Zoom or by phone. Almost all interviews with women were conducted by the nine community-based researchers who were recruited, onboarded, and trained starting in September 2020 by SRBWI and Human Rights Watch. SRBWI and Human Rights Watch staff assisted with follow-up interviews with a few women.

During an initial nine-day training in October 2020, facilitated by SRBWI participatory research consultants and Human Rights Watch researchers, community-based researchers engaged in in-depth training to conduct ethical research to protect the safety and confidentiality of interviewees. SRBWI and Human Rights Watch provided ongoing project supervision and research support through one-on-one check-ins with individual researchers as well as bimonthly group trainings.

Interviews focused on women’s experiences obtaining cervical cancer-related care. The interviews often touched more broadly on the reproductive healthcare needs and experiences of Black women living in rural Georgia who are more likely to live in poverty and be uninsured. Four interviewees reported a personal experience with cervical cancer. Additionally, 27 of the women interviewed had received hysterectomies due to a gynecological problem.

SRBWI and Human Rights Watch also consulted with or interviewed a total of 46 academics, medical providers, public health officials, and members of nongovernmental health and reproductive rights and justice groups in Georgia, including 21 medical providers, public health officials, and experts about their experiences with cervical cancer-related prevention and care.

SRBWI and Human Rights Watch conducted significant background research and quantitative data analysis of secondary sources for this report, including data compiled through publicly available sources and aggregate data about cervical cancer statistics provided by the Georgia Breast and Cervical Cancer Program (BCCP). Any known limitations on data reliability are noted and all documents relied upon are referenced or on file with Human Rights Watch.

Prior to the start of the project, three external advisors, including a community member from southwest Georgia, provided an independent research design review. They reviewed project design and research materials—including informed consent protocols—and provided feedback, which SRBWI and Human Rights Watch worked to incorporate into final materials and design, to ensure that all appropriate steps had been taken to protect the rights of all participants involved in the research project.

All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways that their information would be collected and used. They were also told that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions without negative consequences. All interviewees provided verbal informed consent to participate in the research.

Community-based researchers adhered to specific protocols to ensure that the women they interviewed provided full informed consent to participate in the research. Prior to the start of interviews, women interviewed by community-based researchers received written informed consent to participate in an interview, either through an electronic or hard copy. They were informed of the purpose of the interview; its voluntary nature; the ways that information would be collected, securely stored, and used; any foreseeable risks associated with participating in the interview; and the contact information for project leads from SRBWI and Human Rights Watch. At the start of each interview, community-based researchers reviewed these protocols and received verbal informed consent from each participant. Interviewees were also provided with the option to request that their name remain confidential, and in such cases, we have used a pseudonym in this report. Complete information on informed consent was also publicly available on Human Rights Watch’s website for interviewees to reference at any time.

Community-based researchers received compensation for their time participating in the project, including for each interview they completed. In keeping with Human Rights Watch’s general practice, interviewees did not receive compensation for participating in the research. Interviews lasted anywhere from 25 minutes to over an hour.

All interviews were conducted in English. Community-based researchers identified interviewees primarily through their established connections within their communities. However, outreach strategies, including the use of social media and flyers, were also used to ensure diverse representation of women beyond their known networks.

A Note on Terminology

This report uses the term “woman” in reference to those who are at risk of cervical cancer because the individuals interviewed identified themselves as such. Cervical cancer can impact anyone with a cervix. Even after the removal of a cervix, people may still be at risk of cervical cancer if they had a history of high-grade precancerous lesions or cervical cancer prior to surgery. Human Rights Watch recognizes that cervical cancer also affects people who do not identify as women, including some gender non-conforming people and some men of trans experience. People who are at risk of cervical cancer who do not identify as women face unique challenges in accessing necessary reproductive health care, including cervical cancer care. This report is limited insofar as it does not reflect those unique challenges.

Throughout the report, we use “people of color” when describing individuals and communities who may identify as Black or African American; Hispanic, Latina, or Latinx of any race; Asian or Pacific Islander; North African or Middle Eastern; Indigenous; or multiracial. We use the terminology “Black” in reference to individuals of African descent or those who identify as such. When quoting interviewees or other sources directly, we have not changed the use of “African American.”

The report periodically refers to distances to services in terms of “minutes away.” This reflects an approximation of time provided by interviewees regarding how long a patient would expect to travel by car to reach a facility providing care.

Counties in the Report

Baker County

Baker County is in Georgia’s “Black Belt,” a stretch of rural counties historically defined by rich black soil, with a population of about 3,000 people.[2] Around 44 percent of Baker County is Black and 25 percent of residents live in poverty.[3] Approximately 18 percent of residents under 65 are uninsured.[4] Baker County is a medically underserved area and a “low-income population health professional shortage area” (HPSA) for primary care, meaning there is a shortage of primary medical providers for low-income people within the county.[5] The county is 100 percent underserved for access to broadband[6] and many people in the county struggle with reliable internet access. Baker County is serviced by a 13-county regionwide demand-responsive transit system, yet the county is designated as a health transportation shortage area where barriers to transportation significantly affect access to health care.[7]

Coffee County

Coffee County is a rural county in Georgia with a population of about 43,000.[8] Approximately 29 percent of residents in the county are Black and 20 percent of county residents live in poverty.[9] Around 21 percent of people under 65 in Coffee County lack health insurance.[10] Like Baker County, it is also designated as medically underserved and a low-income population HPSA for primary care.[11] Eighteen percent of the county is underserved for access to broadband.[12] Coffee County also operates a 14-county regionwide demand-responsive transit system but is also considered a health transportation shortage area.[13] Out of the three counties where the research focused, it is the only county that has a hospital and practicing obstetrician gynecologists. Due to civil rights litigation by the Coffee County Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the late 1970s and again in the 1990s,[14] the city of Douglas was redistricted, allowing city residents to elect more Black officials, including the city’s first Black mayor, Tony Paulk, in 2008.

Wilcox County

Wilcox County is a rural county with a population of about 8,600.[15] Approximately 35 percent of residents in Wilcox County are Black and 29 percent of all county residents are living in poverty.[16] Around 16 percent of county residents under 65 are uninsured.[17] Wilcox County is also a medically underserved area and a high needs geographic HPSA for primary care, meaning there is a shortage of primary care providers for everyone living within the county.[18] Fifty-two percent of Wilcox County is underserved for broadband access.[19] The Baxley Office of the Heart of Georgia-Altamaha Regional Commission manages a demand-responsive transit system in Wilcox County; however, services are generally only available for individuals who are clients of the Division of Aging or the Department of Behavioral Health and Disability.[20] The county is also designated as a health transportation shortage area.[21] Two lawsuits filed in the 1980s, one against the city of Rochelle and the other against the county, challenged the at-large voting system and led to redistricting reforms in both the city and county systems.[22]

I. Black Women in Georgia Die from Cervical Cancer at Disproportionate Rates

Cervical cancer is a disease that almost no one should die from, yet every year, Black women in Georgia—and across the United States—die from it at disproportionately high rates. Although mortality rates in Georgia have declined by around 1.4 percent each year since 1990, the American Cancer Society (ACS) estimated that 140 women in Georgia would die from cervical cancer in 2021.[23]

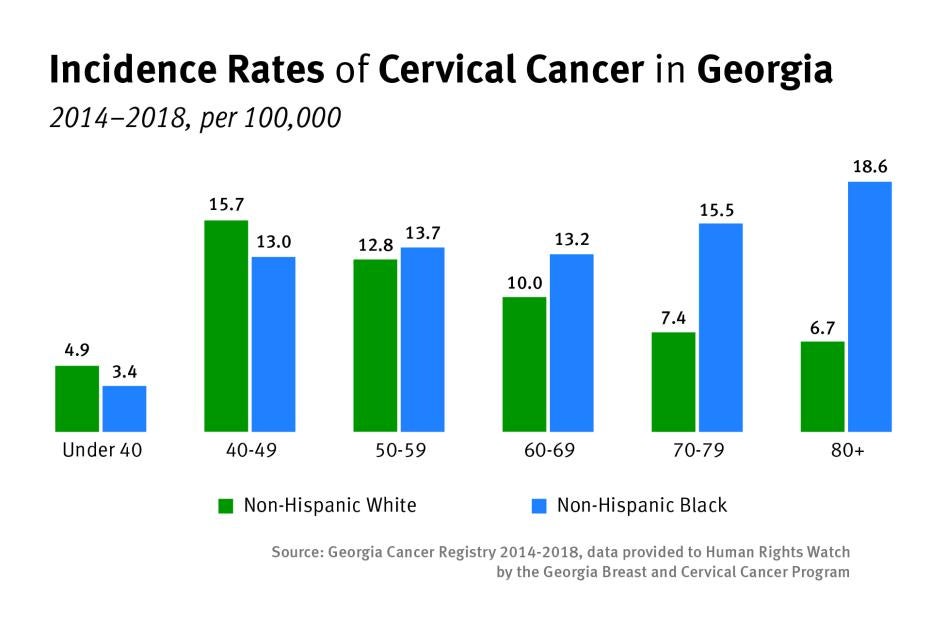

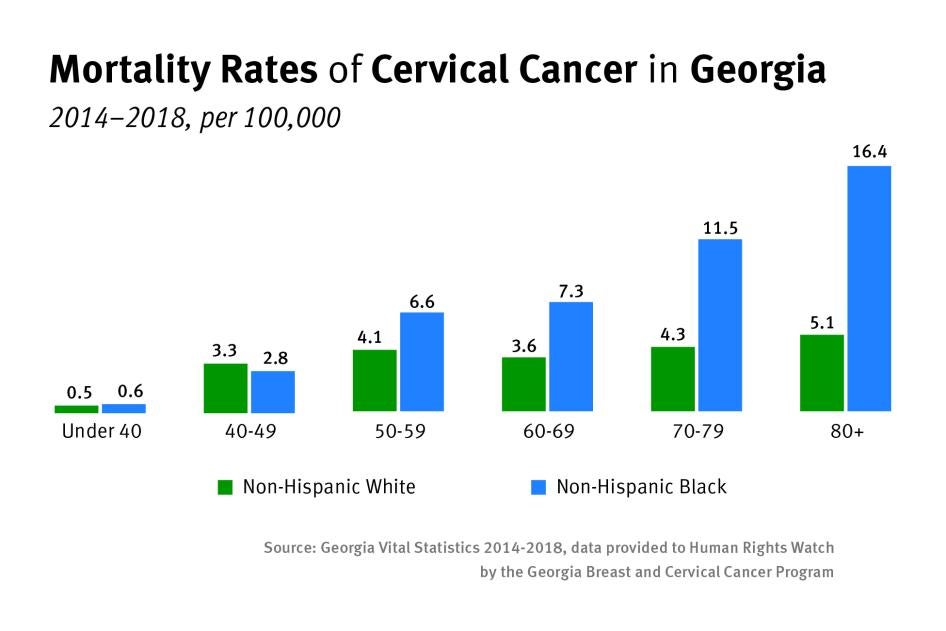

From 2014 to 2018, Black women in Georgia had higher cervical cancer mortality rates in comparison to white women.[24] Although overall incidence rates for white women were 1 percent higher than Black women, Black women were almost one and a half times as likely to die of cervical cancer.[25] These disparities increase at alarming rates as women age, and Black women over the age of 70 are almost three times as likely to die of cervical cancer in comparison to white women in the same age group.[26]

Incidence rates and mortality rates are higher in areas further from metropolitan centers.[27] For all women, cervical cancer mortality is 50 percent higher in smaller urban areas than in major metropolitan centers.[28] Racial disparities are especially glaring in rural areas where Black women face a cervical cancer incidence rate that is almost 50 percent higher than white women. [29]

Compared to white Georgian women, Black Georgian women are more likely to have never been screened for cervical cancer: from 2014 to 2018, 7.7 percent of Black women between the ages of 21 to 65 had never received a cervical cancer screening compared to 4.9 percent of white women.[30] Black women are also more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer at a later stage and have lower five-year survival rates.[31]

Disparities in cervical cancer are consistent with overall health disparities impacting Black people in Georgia as a result of structural racism, discrimination, and exclusion from the healthcare system. Black Georgians are more likely to live in poverty, less likely to have health insurance or adequate access to health care, and face higher rates of chronic health conditions and poor health outcomes.[32]

|

Inadequate Screenings Contribute to Higher Mortality Rates for Older Women Cervical cancer screenings are generally not recommended after age 65 for patients who have been regularly screened in the previous 10 years with normal test results.[33] However, research has found that many women are not receiving adequate screenings as they approach 65 and about 20 percent of cervical cancer cases are diagnosed in women over age 65.[34] As they get older, women are less likely to have received a cervical cancer test in the previous five years.[35] Inadequate screenings, disproportionately impacting marginalized women who lack access to regular and affordable preventive health care, can contribute to cervical cancer incidence rates that increase with age in the US.[36] Incidence and mortality rates are especially high for older Black women.[37] Many women associate cervical cancer screenings with childbearing, a misconception that Dr. L. Joy Baker, an obstetrician gynecologist in LaGrange, Georgia, is familiar with. “I have a lot of patients who have this misconception that once I'm done with childbearing, I can stop getting my Pap tests,” she said. “They associate childbearing with coming to the gynecologist’s office…They don't necessarily consider that they need to continue gynecology appointments once they're done bearing children.”[38] Greater access to information on sexual and reproductive health can help address misconceptions and misunderstandings around cervical cancer screenings that contribute to preventable cervical cancer deaths for older women. Current guidelines, which generally recommend stopping cervical cancer screenings at age 65 for women who have been adequately screened, may be missing opportunities to prevent cervical cancer incidences and deaths in older women.[39] At the same time, these guidelines may also contribute to poor cervical cancer outcomes that disproportionately affect older Black women who face an increased risk from the disease.[40] |

II. Inadequate Access to Reproductive Health Care Limits Cervical Cancer Care in Georgia

I think what would help would be […] access. Access to the care that they need, meaning clinics, open... Even more doctors. Availability of doctors and healthcare professionals. … We need access right there in Baker County, because a lot of the times, there is not.

—Veronica C. (pseudonym), 71, Baker County, Georgia, February 7, 2021

Cervical cancer develops over several years, providing ample time to detect and treat early abnormal changes in cervical cells that could eventually lead to cancer.[41] With access to routine gynecological care, including screenings, most cases of the disease can be prevented. Yet the state of Georgia’s failure to ensure comprehensive access to reproductive health care has left marginalized and low-income women struggling to obtain the lifesaving services and care they need to prevent and treat cervical cancer.

Georgia Fails to Ensure Consistent and Affordable Coverage for Cervical Cancer Care

Health insurance status plays a pivotal role in the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer, which requires routine contact with the healthcare system throughout the course of a woman’s lifetime. Yet Georgia lacks a comprehensive approach to guaranteeing access to health care, instead relying on a patchwork of multiple, publicly funded programs to extend healthcare coverage to low-income women in the state, including for gynecological care. Women who are uninsured have lower cervical cancer screening rates, a higher risk of late-stage diagnosis, and lower rates of cervical cancer survival in the US.[42] Without access to consistent and affordable reproductive healthcare

services, low-income and uninsured women are left navigating gaps in coverage and financial barriers to cervical cancer care.

Georgia Has Not Expanded Medicaid to Increase Healthcare Coverage for Low-Income Georgians

Georgia’s government could have extended affordable healthcare coverage to more low-income adults by expanding Medicaid eligibility through a funding match opportunity created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but at time of writing, it was 1 of 12 states that had not done so.[43] Instead, the state is currently awaiting re-approval of a waiver plan that would partially expand Medicaid coverage while also imposing work requirements on newly eligible adults.[44]

States have had the option to expand Medicaid coverage with federal funding support since the 2010 passage of the ACA. Each year Georgia does not do so, the state loses out on $3 billion dollars of federal funding for healthcare coverage.[45] At the same time, approximately 255,000 Georgians are uninsured with no affordable option for health insurance.[46] Full expansion of Medicaid in Georgia would extend coverage to people making up to $17,774 per year, closing the coverage gap and providing affordable health insurance to approximately 470,000 low-income Georgians.[47]

This has contributed to high rates of uninsured Georgians, with disproportionate impacts on people of color. An able-bodied adult who is not a caregiver or pregnant is not eligible for full Medicaid coverage in Georgia, no matter how poor the individual is. As of 2018, approximately 14 percent of the population in Georgia was uninsured—the third highest rate in the US after Texas and Oklahoma—with estimates that the uninsured rate in rural Georgia could surpass 25 percent by 2026.[48]

|

Medicaid Expansion Could Help Reduce Racial Disparities in Access to Healthcare Coverage and Health Outcomes People of color have been particularly affected by the unwillingness of states to expand Medicaid. States that did not expand Medicaid—the majority in the southeastern US, like Georgia—have higher proportions of Black people, people of low socioeconomic status, and uninsured people than those that did expand their Medicaid programs.[49] People of color are disproportionately represented in the coverage gap with no affordable option for health insurance and in 2019, approximately 60 percent of those in the coverage gap across the US were people of color.[50] Along with most other states that did not expand Medicaid, Georgia has a high rate of uninsured Black people compared to expansion states. Black people account for approximately 36 percent of Georgians in the coverage gap.[51] By increasing healthcare coverage for more low-income people of color, Medicaid expansion could help reduce racial disparities in health outcomes arising from unequal access to affordable and comprehensive healthcare coverage. |

Medicaid expansion improves access to health care and health outcomes. It increases affordability of care, improves access to and utilization of healthcare services, and reduces rates of uninsured patients and uncompensated healthcare costs.[52] Compared to uninsured individuals, people enrolled in Medicaid are more likely to report seeing a doctor or specialist in the past year and are less likely to delay medical care.[53] Expanding Medicaid also improves access to comprehensive cancer care. It increases the use of preventive healthcare services—leading to earlier detection and more effective treatment of cancer—and has been associated with increased screening rates, earlier diagnosis of cancer, and a higher likelihood of survival after diagnosis.[54] At the same time, people who are uninsured are more likely to forgo preventive health care, including timely cancer screenings, and are also less likely to receive the optimal cancer care they need.[55] Research has shown that low-income women living in states that have not expanded Medicaid are significantly less likely to receive a Pap test than those living in expansion states, with the lowest screening rates for uninsured women.[56]

A Patchwork of Federal and State Programs Provides Inadequate Reproductive Healthcare Coverage for Low-Income and Uninsured Georgian Women

Instead of providing comprehensive and affordable healthcare coverage, Georgia relies on various state and federal programs to cover reproductive healthcare services for select low-income women who do not qualify for full Medicaid. This patchwork of programs, each with different eligibility criteria and scope of services covered, creates fluctuating access to healthcare coverage and gaps in cervical care, especially for necessary follow-up care.

In Georgia, pregnant women can receive full Medicaid benefits if their income is at or below 220 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $38,324 per year as of 2021.[57] However, this coverage ends 60 days after they give birth.[58] Planning for Healthy Babies, the state’s family planning program, provides no-cost family planning services for uninsured women between 18 and 44 who are able to become pregnant and who qualify with incomes at or below 211 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $27,177 per year as of 2021.[59] Planning for Healthy Babies covers annual Pap tests and pelvic exams, but not follow-up diagnostic services after abnormal cervical cancer test results.[60]

Uninsured and low-income Georgian women can also receive low-cost reproductive healthcare services, including Pap and HPV tests, based on a sliding scale at county health departments located in each of Georgia’s 159 counties.[61] However, follow-up testing after abnormal cervical cancer screenings, including colposcopies, are not performed at many health departments, requiring follow-up with a gynecologist or a referral to another health department that may provide these more expensive services. In addition, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) receive federal funding to provide essential primary and preventive healthcare services to low-income Georgians. There are currently 34 FQHC networks throughout the state where Georgians can receive healthcare services on a sliding scale fee, including Albany Area Primary Health Care in Baker County, South Central Primary Care in Coffee County, and CareConnect in Wilcox County, yet like the health

department, follow-up diagnostic testing is not available at all FQHCs located in these counties.[62]

Women are not always aware that resources for low-cost reproductive health care services exist. Although almost all of the women with whom SRBWI and Human Rights Watch spoke knew there was a health department in their county, a few did not. Even for those women who know about their local county health department, many said they had never gone there for services and many reported not knowing the services health departments offer. Patricia R. (pseudonym), 31, had visited the health department in Coffee County in the past for contraceptive care but believed many women in her community do not know about affordable resources for reproductive health care: “I am sure there are resources out there, but I think in my community they should bring more awareness to it because there's a lot… of people here [that] don't know about [them].”[63]

Dr. L. Joy Baker, an obstetrician gynecologist working at a private practice in LaGrange, a small town in west-central Georgia, also described a lack of information on affordable reproductive health resources in her community:

I find a lot of people don't know that they can go to the health department and they can make appointments for you to come in for your Pap, or for contraception, or that sort of thing. A lot of people just only think about the traditional healthcare setting, where it's a doctor's office, or a clinic, and they're not necessarily aware that they can get a Pap at the health department.[64]

Georgia Breast and Cervical Cancer Program Provides Critical Cervical Cancer Care but is Limited by Funding Challenges

The Georgia Breast and Cervical Cancer Program (BCCP) fills a critical gap in connecting low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women to comprehensive cervical cancer care.[65] It is the only public program, funded with state and federal funds, that provides no-cost colposcopies and diagnostic testing for uninsured and underinsured women in Georgia, yet funding challenges significantly limit the number of women the program can serve.

In addition to providing no-cost cervical cancer screenings and diagnostic services following abnormal test results, the BCCP refers enrolled women who are diagnosed with cervical cancer, including precancerous conditions, to Women’s Health Medicaid, a partially federally funded state program that covers the cost of breast and cervical cancer treatments for uninsured or underinsured women under 65 who cannot afford treatment.[66] Eligible women who are diagnosed with cancer while not enrolled in the BCCP can also receive treatment through Women’s Health Medicaid. Women’s Health Medicaid covers a woman for a year and is renewed annually if she is still in cancer treatment. Once a woman is cancer free, other medical assistance has to be sought.[67]

Although the BCCP plays an important role in connecting low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women to comprehensive cervical cancer care, funding challenges and a public health nursing shortage and turnover significantly limit the program’s ability to recruit and serve eligible women. Federal funding from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) and matching Georgia state funding are inadequate to cover the program’s operating costs. In 2017, the US Department of Health and Human Services cut the NBCCEDP budget by $40.8 million, about 15 percent of its total budget, and federal funding has remained stagnant over the past few years.[68] Since 2019, the BCCP has received $4.6 million each year in federal funding for the program.[69] State funding for the BCCP, which has also remained unchanged over the past few years, is inadequate.

Limited funding affects the BCCP’s ability to provide direct cervical cancer services to Georgian women, and in 2018 the program was serving less than 2 percent of women eligible for cervical cancer services.[70] Since 2017, the CDC has shifted NBCCEDP state grants to incorporate health systems changes aimed at increasing breast and cervical cancer screening rates.[71] In addition to providing direct services, the BCCP must now also use limited funding to cover the cost of implementing health systems interventions, including partnering with four FQHCs to implement evidence-based interventions, such as client reminders, to increase cervical cancer screening rates.[72] Unlike states that have expanded Medicaid, Georgia still has a large population of uninsured women in need of cervical cancer coverage. Diverting funding away from direct service work impacts the number of women for whom the program is able to cover direct medical benefits for cancer screenings and diagnostic services.[73]

Lack of staff capacity within public health districts is another challenge for the BCCP, in the context of a severe state nursing shortage and high turnover rate.[74] The majority of funding for the BCCP is used for direct client services, leaving little financial support for nursing staff working within county health departments who are not employed by or paid by the BCCP but are responsible for screening women enrolled in the program.[75] Multiple and competing responsibilities, such as dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic, can impact nursing staff’s capacity to screen women through the BCCP and the program’s effectiveness in reaching women.[76]

As a result of limited funding, the BCCP also only employs eight patient navigators who cover a very limited portion of the state despite the instrumental role they play in connecting marginalized women to timely and comprehensive cervical cancer care.[77] Evaluations of the BCCP have found that the patient navigation program is effective, not only in facilitating timely access to cancer screenings and diagnostic testing, but also in reducing disparities underserved women face in accessing cancer care.[78] Patient navigators conduct outreach to educate communities about breast and cervical cancer and recruit eligible women for the program. They also deliver one-on-one and group education, address diverse barriers to care women may face—including lack of information, fear, language barriers, and childcare and transportation challenges—and assist women in navigating through a complex health system at all stages from screening to diagnosis.[79] Phanesha Jones, who worked as a BCCP patient navigator in the North Central Health District until August 2021, described the role she played in ensuring women received timely and follow-up care:

So, there would be women who are overdue or due for their annual appointment, and part of my role is to reach back out to those women and remind them of their annual appointment and guide them and hold their hand through the continuum of care until they reach the end.[80]

The eight patient navigators currently employed by the program work in seven public health districts and with one FQHC located in Atlanta,[81] but they cannot reach marginalized women throughout the state. This leaves women in 11 of Georgia’s 18 health districts without access to an important resource for comprehensive cancer care.[82]

Despite low enrollment numbers relative to the number of women in the state eligible for the program, outreach around the BCCP is limited and many women do not know about the program. The program relies primarily on word of mouth for outreach. “It is hard because I know when we are in the community, many people say ‘Where have you been? I’ve never heard about this program before,’” Olga Jimenez, BCCP patient navigation program manager, told Human Rights Watch. “There are not enough patient navigators and other health educators in the community talking about the program.”[83] Only a small number of the women whom SRBWI and Human Rights Watch interviewed were aware of the program.

The BCCP does not have adequate funding to serve all eligible women in the state and mass outreach would further strain the program’s already limited resources.[84] Inadequate funding to support the program’s outreach, staffing, and direct service provision means that vulnerable women in Georgia will continue to miss out on a program that could save their lives.

Lack of Comprehensive and Affordable Healthcare Coverage Creates Barriers to Cervical Cancer Care

Almost all cases of cervical cancer can be prevented with routine screenings and follow-up care to detect and treat precancerous changes in cervical cells, yet the state of Georgia’s failure to ensure comprehensive access to affordable health care has created barriers for women in need of consistent cervical cancer care. SRBWI and Human Rights Watch interviewed women who described their struggles to afford the cost of routine cancer screenings and necessary follow-up care. For many of these women—the majority of them uninsured—their inability to afford reproductive healthcare services meant that they often avoided medical appointments and skipped cancer screenings altogether. Many were not aware of the stop-gap programs discussed above, even though they might have met eligibility criteria. This is consistent with data that has found women without health insurance in Georgia are almost 30 percent less likely to receive routine cervical cancer screenings than insured women.[85]

Barbara L., 53, from Douglas County, was diagnosed with cervical cancer while in her late twenties. Leading up to her cancer diagnosis, Barbara was uninsured and did not receive routine cervical cancer screenings. “I did not have a habit of going to the doctor because I had to pay,” she explained. “I wasn’t the type to keep up with stuff like that and when I did, that is when I found out [that I had cervical cancer].”[86] Michelle R. (pseudonym), 23, from Baker County, has been uninsured for five years. Although she knows that she should be going for regular cervical cancer screenings, she has not gone because of the cost. “Because I can't afford it, I don't go… When you can't afford it, what can you do?” she said.[87] Rachel P. (pseudonym), 52, from Baker County, is uninsured and does not routinely receive cervical cancer screenings. She said her inability to afford the cost of a doctor’s visit affected her access to gynecological care: “I don't have health insurance, and then it gets to be expensive. And then sometimes I just won't go because I don't have the finances.”[88] Charlene E., 57, from Wilcox County, has several friends who need to see a gynecologist but “because they don't have money, they don't… you just don't go.”[89]

Patricia M., 51, from Wilcox County, is currently uninsured and cannot afford to go to medical appointments. She had an appointment scheduled with a gynecologist to follow up on a hormonal issue but had to cancel the appointment because she could not afford it. “I couldn’t go see him [the gynecologist] because I didn’t have [the] money. They was going to charge me like 200-something dollars to come see them because I didn't have no Medicaid,” she said.[90] It’s been over a year and Patricia still hasn’t been able to afford the care she needs. She also said that she does not go to the county health department because even the reduced costs of services are prohibitive: “I really don’t have the money to go there either.”[91]

Women also described how their health choices and ability to seek reproductive care shifted along with their insurance status, leaving periods of time when they have been unable to access preventive screenings and follow-up care. Sheneka G., 41, from Wilcox County, works as a certified nursing assistant but has been uninsured for years because she cannot afford it and it’s not available through her employer. Her last Pap test was seven years ago while she was on Medicaid for pregnant women. Since losing her healthcare coverage after her child was born, she has not had another cervical cancer screening.[92] Like Sheneka, Shonterria W., 32, from Crisp County, also last had a Pap test when it was covered through Medicaid while she was pregnant. Since then, she has been uninsured for eight years. She has not gone back to see her gynecologist, who is only five miles from her home, because she cannot afford it.[93] Monica B. (pseudonym), 42, from Coffee County, is currently insured and regularly receives cervical cancer screenings. She explained that in the past when she was uninsured, she wasn’t able to access reproductive health care because she could not afford it: “It was times where I needed to make appointments and wasn't able to afford it because of me not having insurance. So, I wasn't able to.”[94]

Ilene R., 62, from Coffee County, said that after years of abnormal Pap tests, her doctor discovered what Ilene understood was a tumor that needed to be removed immediately. Her doctor told her she was on the verge of being diagnosed with cervical cancer. Through the health department, she was enrolled in a program—most likely Women’s Health Medicaid—and received the surgery. However, she is no longer enrolled in the program and has experienced periods of being uninsured, which has affected her ability to seek routine gynecological care—especially important for someone with a history of a precancerous condition. Ilene last went to see her gynecologist, who is only three miles away from her home, two years ago, but because she was uninsured, has not gone back since.[95]

Jessica N. (pseudonym), 26, from Baker County, described a period of three years when she was uninsured and not able to afford reproductive healthcare services:

The job that I was working didn’t provide health insurance for the employees and I wasn’t making enough money to be able to afford health insurance on my own. And so, during that time, that was a long period of me either not going to the doctor…and getting the checkups and the treatment that I needed, or me paying a lot of money.[96]

In addition to forgoing appointments altogether, women also described difficult choices they have been forced to make at times when they cannot afford the cost of reproductive health care. Although she currently has insurance coverage, Tara B. (pseudonym), 61, from Wilcox County, is unemployed and sometimes struggles to afford co-payments to see the doctor. In addition to rescheduling appointments at times if she cannot afford the cost, she said that sometimes she has to decide whether to pay her medical bills or buy food: “Well, sometimes it's a bill, or sometimes it's food. I leave out certain food.”[97]

Toni R., 45 from Wilcox County, has had health insurance on and off for the past seven years because she cannot always afford it. She’s currently uninsured and described difficult choices she has had to make during periods when she struggles to pay for reproductive health care, including cutting down on groceries or not paying household bills:

I guess it's kind of a matter of you deal with it until you can't deal with it anymore… [W]hich basically means that you kind of get into an emergency type situation… That’s kind of how it's been. Bills that you have to pay monthly, your monthly expenses. You may not buy as many groceries, you may skip … the internet bill. You may even put off a mortgage payment, just because you've got to have the services.[98]

Although resources exist to provide low-cost cervical cancer screenings and diagnostic testing for low-income and uninsured women, including services offered on a sliding scale at county health departments and FQHCs, even these reduced costs can be unaffordable for some women, especially when factoring in the cost of laboratory fees. Follow-up care after abnormal test results is even more expensive, yet essential for preventing cervical cancer.[99] Despite being necessary aspects of cervical cancer prevention, colposcopies and biopsies are not covered as preventive services under the ACA essential benefit mandate or as family planning services under Planning for Healthy Babies.[100] This can create significant financial burdens to obtaining affordable follow-up care, even for women who are insured and have coverage for preventive screenings.

In addition to challenges accessing preventive cervical cancer screenings, women interviewed also described how a lack of affordable healthcare coverage impacted their ability to seek necessary follow-up gynecological care. Latosha M., 25, from Wilcox County, is insured through Medicaid but struggles to afford her co-payments: “You know, you go into an office… expecting to get the service done. When you get in there, you have to pay a co-pay and you don't have that co-pay, so all you got to do, just walk back out the door or hope they'll take you in without the co-pay.”[101]

Felicia C. (pseudonym), 21, from Wilcox County, reported having a recent Pap test that came back as abnormal. The additional testing she needs is not covered under the insurance plan she is on, so she has not gone back for follow-up care: “She [the nurse] told me to come back … but she said I would have to pay for it to get the information and get the test done over again. I couldn't afford it, so I just didn't go back.”[102]

After years of routine cervical cancer screenings at her county health department, Lisa D. (pseudonym), 62, from Wilcox County, started receiving abnormal Pap test results while in her mid-thirties. For about four years, Lisa received follow-up and more frequent Pap tests, all with abnormal results.[103] Eventually, she received cryotherapy to freeze and treat abnormal precancerous cells, but the procedure was unsuccessful at treating her condition. Her doctor told her she needed an immediate hysterectomy, referring to it as “a matter of life or death.” This was especially concerning to Lisa since her mother had died of cervical cancer. However, she was uninsured at the time and could not afford the surgery. “I couldn’t get it done right away because I didn’t have insurance,” she said.[104] After waiting several months, Lisa was finally approved for Medicaid and able to get the lifesaving surgery she needed.

Dr. Baker has seen firsthand the impact that lack of access to affordable gynecological care has on her patients. In her experience, women who cannot afford cervical cancer screenings or diagnostic tests just do not get them, a scenario she finds “really unfortunate because cervical cancer is almost completely preventable in most circumstances.”[105] She said that almost every day she encounters patients who point to a lack of consistent and affordable health insurance as a barrier to routine gynecological care: “I'll see women that come in almost on a daily basis and say, ‘I haven't been seen in 5 years, 8 years, 10 years, 20 years. I was between insurances and I couldn't come back to follow up on my abnormal Pap,’ or that sort of thing. I get that all the time.”[106]

Janet Anderson is a licensed practical nurse at Baker County Primary Health Care, an FQHC. Even though services are offered at the clinic on a sliding scale, she described how some patients avoid Pap tests because they cannot afford the laboratory fees. According to Janet, when asked if they would like to receive a Pap test during their visit, some patients will say, “Well, no, because I'm getting a bill from the lab and I can't afford to pay them. I don't really want to do that.”[107] Staff try to encourage patients to get the test, but Janet understands the hesitancy: “[I]f you can't afford it, you can't afford it.”[108]

Dr. Favors, an obstetrician gynecologist working in Dougherty County, which adjoins Baker County, also described how a lack of affordable health care affects access to cervical cancer care, particularly follow-up care. She said that in her experience working with low-income Georgians at a clinic providing low-cost reproductive healthcare services, most patients are typically able to afford initial Pap and HPV tests through the clinic’s sliding-scale fees or programs that completely cover the cost of the screenings. However, even on a sliding scale, the cost of follow-up procedures after abnormal test results is prohibitive for some patients:

I think where the barrier comes in is when it's time for them [patients] to have a procedure done, because that unfortunately isn't free. It may be only a small fee, but for some patients, that small fee might be a lot of money.[109]

Despite costs they might struggle to afford, a lot of patients try and figure out a way to afford follow-up treatment, and the clinic works with them to help them get the care they need. But Dr. Favors has some patients who simply do not return: “We do have some patients that say, ‘Yeah, I can't afford that’ and then disappear if they can’t afford the procedure.”[110]

Access to Gynecological Care is Limited in Georgia, Especially Rural Areas

Along with financial barriers to affordable health care, limited access to gynecological care—exacerbated by a shortage of gynecologists in Georgia and inadequate transportation—creates additional challenges for underserved women in need of cervical cancer care, especially those living in rural areas.

Georgia’s Failure to Expand Medicaid Contributes to a Shortage of Obstetrician Gynecologists

A lack of obstetrician gynecologists in Georgia creates additional barriers to cervical cancer care, making access to gynecological care burdensome, costly, and even nearly impossible for some women. Currently, Georgia faces a severe shortage of obstetrician gynecologists and almost half of the state’s 159 counties do not have 1, with rural areas particularly impacted.[111] The closure of hospitals and labor and delivery units in the state has contributed to the shortage.[112] When hospitals and labor and delivery units close, and obstetricians, who are typically also gynecologists, have nowhere to deliver babies or provide emergency obstetric care, they often move away, leaving entire communities without access to essential pregnancy and gynecological services. Since 2010, Georgia has had seven rural hospitals close—tying Oklahoma for the third most rural closures in the country—and 38 labor and delivery units have shut down since 1994.[113]

Georgia state policies have contributed to the crisis. Hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid have seen increased healthcare coverage, decreased uncompensated care for uninsured patients, and have been shown to be significantly less likely to close than hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid.[114] By expanding Medicaid, Georgia could increase healthcare coverage to more low-income people in the state, decreasing the cost of uncompensated care and providing a financial lifeline for hospitals struggling to stay afloat, especially in rural areas. Yet the state government has chosen not to do so, fueling a shortage of obstetrical and gynecological care in rural areas.

|

Restrictive Policies Around Women and Girls’ Reproductive Rights in Georgia In addition to screenings and the HPV vaccine, a comprehensive approach to effective cervical cancer prevention requires policies that support women and girls’ sexual and reproductive health and rights. Yet policies in Georgia restrict access to the reproductive healthcare services and information women and girls need to make decisions around their reproductive future and to control the number and spacing of their children, including contraceptive and abortion information and services. Georgia currently ranks in the bottom tier of US states in terms of reproductive health and rights.[115] Policies seeking to further curtail reproductive rights, including anti-abortion bills, would further limit women and girls’ autonomous decision-making about their reproductive future and access to the full spectrum of reproductive health care that they need to manage their cervical cancer risk, which includes giving birth often or at a young age.[116] These restrictive policies could also exacerbate Georgia’s shortage of obstetrician gynecologists by deterring doctors and medical residents from practicing in the state.[117] |

A lack of gynecologists makes it difficult for rural women to access consistent cervical cancer care. Many women often go see a gynecologist only when problems arise, leaving periods of time when they are missing out on essential cancer screenings. Phanesha Jones, a former BCCP patient navigator, said that distance from medical providers affects access to regular gynecological care for women in rural Georgia:

Here in Georgia, most women in the rural areas don't regularly see a doctor because the doctors may be far away from where they live. So, I think that most of the time they will go when there's a problem presented. A lot of times we deal with women who are overdue for a screening or they're coming in because they have a problem.[118]

A lack of gynecologists in rural communities also creates additional challenges for women who need follow-up care after abnormal test results. Although low-cost cervical cancer screenings are available locally throughout Georgia, at county health departments and FQHCs, colposcopies and follow-up procedures require care by a specialist, typically a gynecologist but a nurse practitioner can also perform the procedure.[119] Additional treatment after diagnostic testing, such as procedures to remove precancerous cervical cells, requires care by a gynecologist. This lifesaving follow-up care is even less accessible when women have to travel far distances for the services they need.

|

An Overview of Gynecological Care in Baker, Coffee, and Wilcox Counties There are no gynecologists in Baker County and neither the county health department nor the local FQHC perform colposcopies, so women have to travel to Albany, in Dougherty County, to visit the nearest gynecologist for follow-up care, around a half-hour drive.[120] The Baker County Health Department refers women to either a private provider of the patient’s choice or to the Miriam Worthy Women’s Health Center, an FQHC in Albany, for follow-up care. Baker County Primary Health Care, the local FQHC, refers women to one of two women’s health clinics within the Albany Area Primary Health Care network in Albany. |

Georgia Lacks Adequate Transportation, Creating Additional Barriers to Cervical Cancer Care

Compounding a shortage of gynecologists, Georgia’s inadequate public transportation system throughout the state, especially in rural counties, makes accessing cervical cancer care even more difficult. Women often face challenges in securing adequate transportation, paying to get to and from appointments, and long travel times, all of which affect their ability to receive routine and timely care. These additional transportation challenges mean some women delay gynecological care and others forgo it altogether.

Research by Georgians for a Healthy Future has found that transportation is a barrier to health care for a large portion of Georgia’s population and 117 out of Georgia’s 159 counties are considered health transportation shortage areas.[121] In these counties—which are more likely to be rural with limited or no public transportation options, high rates of poverty, and fewer medical providers—residents face significant transportation barriers that impact access to health care.[122] The Southwest region, including Baker, Coffee, and Wilcox counties, was found to have the greatest transportation barriers to health.[123]

Georgia does not provide adequate state funding for transit, leaving many rural transit systems struggling to operate. Through the Federal Transit Administration’s Section 5311 Rural Public Transportation Program, rural transit systems can apply for matching federal funding dispersed through the Georgia Department of Transportation to support public transit.[124] Local funds are required to match federal funding and state contributions towards transit systems are minimal.

SRBWI and Human Rights Watch interviewed women who described having to travel long distances to see a gynecologist, which impacted their ability to obtain routine and follow-up care. Rhonda T. (pseudonym), 28, from Wilcox County, travels over an hour each way to see her gynecologist, a trip that costs her approximately $80 roundtrip through a rideshare. She describes transportation as a challenge she faces in getting reproductive healthcare services.[125] Brenda P., 47, from Wilcox County, has to travel 45 minutes to get to her gynecologist’s office and sometimes doesn’t have money for gas. She described transportation as a barrier to accessing health care, “especially when I don't have the money to put the gas and stuff in to go places, go back and forth.”[126]

Women who are on Medicaid or are uninsured often need to travel longer distances since reduced-cost services are more limited. After years of abnormal Pap tests while in her mid-30s, Lisa D. (pseudonym), 62, needed to travel from Wilcox County to Augusta, Georgia, to see a gynecologist for a follow-up procedure, approximately a three-hour trip each way. Although the appointments were covered by a program through the health department that she is unsure of, she didn’t receive any assistance with transportation. Within a month, she had to make three trips to see the gynecologist in Augusta, a journey she described as too long and too expensive.[127]

Dr. Favors described how women in need of reduced-cost reproductive healthcare services often face additional transportation barriers to receiving care:

I know for a fact that a lot of my patients haven't attempted to go to private doctors because they just can't afford it. So we are that resource, which is a limitation because going to a private doctor may be the person that's closest to them. … There are gynecologists in some of these smaller communities, but they're private doctors. So then they [women] have to get to a place where there's a health department or clinic.[128]

Local transportation options are inadequate for meeting the transportation needs many communities face and can be extremely costly for women who have to travel between counties for medical care, if this option is even available. Demand-response transportation systems, also known as paratransit, which operate in 117 counties throughout Georgia, typically serve a select population and limited availability of services and fixed routes limit their effectiveness in connecting individuals with healthcare services.[129] Both Baker and Coffee counties are serviced by regionwide transit systems, coordinated through regional commissions. Although these systems service all county residents, they require advance notice, and they can be costly for women who need to travel between counties and far distances.[130]

Because of challenges with non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), which provides free transportation to medical appointments for Medicaid enrollees, many qualifying individuals do not take advantage of this assistance. Too few Medicaid enrollees know about the program; at times it picks people up late or not at all for appointments; it requires advance notice to schedule rides; and some vehicles are not accessible for individuals who use wheelchairs.[131] Additionally, parents enrolled in Medicaid are not always able to bring their children to appointments using NEMT, which can force them to choose between medical care or caregiving responsibilities.[132]

Latosha M., 25, lives in Wilcox County and is currently enrolled in Medicaid. She relies on NEMT to get to and from her medical appointments. She described how challenges with NEMT affect her ability to get to appointments:

It really is [challenging] with the transit system… because either they forget where you stay or they continue to get new people to come and pick you up and they act like they don't have your number to call you and ask you where you stay or drive right past or they don't even come at all. … If the transit system were fixed, it wouldn't be so hard [to get to appointments].[133]