Summary

When “Elena” (not her real name) discovered she was pregnant at age 16, she carefully considered her options and decided she was not ready to parent. She knew she wanted an abortion, but she wasn’t able to discuss her decision with her mother. “My mother is very strict with me,” she told her doctor. “If she knows I’m pregnant, she’ll definitely throw me out of the house…. I talked to my boyfriend about moving in with him, but he lives with his mother and several younger siblings, and he sleeps on the couch. He already sleeps on the couch, where am I going to sleep? On the floor?’”

Illinois, where Elena lives, is among the 37 US states that mandate parental involvement for young people under 18 seeking abortion care. Illinois’ Parental Notice of Abortion Act (PNA), in effect since 2013, requires a healthcare provider to notify an “adult family member” of any patient under 18 at least 48 hours in advance of providing an abortion. Under the law, only a parent, grandparent, step-parent living in the home, or other legal guardian over the age of 21 qualifies as an adult family member who may be notified. Young people who wish to obtain an abortion without notifying one of these qualifying adult family members can go through an alternative “judicial bypass” process to demonstrate to a judge that they are 1) sufficiently mature and well enough informed to make an abortion decision without parental involvement, and/or that 2) parental involvement is not in their best interests.

Roughly 1,000 Illinois residents under 18 have abortions in the state each year. The majority of them voluntarily involve a parent or other qualifying adult family member in their decision. Dr. Erin King, an obstetrician-gynecologist and executive director of Hope Clinic for Women, analyzed data on young people seeking abortion care at her clinic before and after Illinois’ parental notification law went into effect: “We know that prior to this law going into effect, over 85 percent of minors were involving a parent anyway. Patients who feel like involving a parent is helpful in their decision-making were already doing that without the law.”

However, a subset of young people like Elena do not want to involve a parent in their decision. They often fear physical or emotional abuse, being kicked out of the home, alienation from their families or other deterioration of family relationships, or being forced to continue a pregnancy against their will. In some cases, young people in these circumstances are able to navigate the judicial bypass system, as Elena did. Others opt to notify a parent, even when it is not in their best interests, and suffer whatever consequences that may bring. Others simply do not access abortion care and continue unwanted pregnancies against their wishes.

This report, a collaboration between Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Illinois, examines the harmful consequences of Illinois’ parental notification law. Based on in-depth interviews conducted with 37 people, as well as analysis of data and other information collected by the ACLU of Illinois between 2017 and 2020 about young people pursuing the judicial bypass process, the report shows that PNA undermines the safety, health, and dignity of young people under 18, whether they elect to notify a qualifying adult family member or to go through judicial bypass. Human rights experts have consistently called for the removal of barriers that deny access to safe and legal abortion and have commented specifically on parental involvement requirements posing a barrier to abortion care. This report includes a detailed analysis of international human rights law and concludes that PNA violates a range of human rights, including young people’s rights to health, to be heard, to privacy and confidentiality of health services and information, to nondiscrimination and equality, to decide the number and spacing of children, and to be free from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Young people who are unable to pursue judicial bypass or find the process too daunting may be compelled to continue unwanted pregnancies or pushed to involve unsupportive or even abusive parents who threaten their safety, interfere in their decision-making, or humiliate them. Even when young people are able to navigate the judicial bypass process, it is burdensome and delays their access to abortion care. Appearing before a judge to request permission to see through an abortion decision is highly stressful for young people, and even traumatizing for some. Participating in the process also risks violating their privacy and confidentiality.

The overwhelming majority of requests for judicial bypass have been granted since the PNA law went into effect, demonstrating the futility and unfairness of forcing young people to jump through so many hoops to exercise their right to access abortion, which is constitutionally and statutorily protected and internationally recognized.

A bill before the Illinois General Assembly, House Bill 1797/Senate Bill 2190, would repeal parental notice of abortion and ensure young people under 18 can access safe, timely abortion care. Illinois legislators should affirm the human rights and dignity of young people under 18 by supporting the bill and voting to repeal parental notice as a matter of urgency.

***

Abortion is the only type of pregnancy-related health care for which Illinois law requires young people to involve their parents. Young people under 18 can access contraceptive methods to prevent pregnancy, decide to continue a pregnancy, access prenatal care, make decisions around labor and delivery, and consent to a caesarean section without involving a parent. Young people can also choose to place a child for adoption without any requirement of parental involvement.

In an analysis of the reasons given for seeking judicial bypass by young people who went through the process between 2017 and 2020, about 40 percent said they were concerned about being forced to continue the pregnancy. Forty percent had concerns about being kicked out of their house or cut off financially. Young people also cited fear of deterioration of family relationships (30 percent), fear of physical or emotional abuse (9 percent), or concerns due to fragile or unstable family situations (11 percent) (many young people identified multiple reasons for pursuing judicial bypass). These fears are often based on observing the lived experience of an older sibling or other family member, or their parents’ explicit statements or threats. Some young people have minimal or no contact with one or both of their parents, for example because of parental death or incarceration, or have ambiguous legal guardianship situations.

Young people who do not involve a parent in their abortion decision often have support from other trusted adults in their lives, but who may not meet the definition of a qualifying adult family member under Illinois’ PNA law. Young people may turn to “an older sister, a partner’s family members, an aunt, a cousin,” explained Dr. Rebecca Commito, an obstetrician-gynecologist in Chicago. “Families look different. Young people find a support person in another way.”

Since 2013, the ACLU of Illinois has operated a Judicial Bypass Coordination Project (JBCP) that provides information about the state’s parental notice of abortion law and the judicial bypass process and offers free legal assistance to young people in judicial bypass proceedings. Despite the strenuous efforts of a compassionate and dedicated network of care providers, attorneys, and volunteers, young people in Illinois still face formidable logistical hurdles throughout the judicial bypass process, particularly around accessing information, communicating safely, scheduling hearings, and securing transportation. Many young people are understandably overwhelmed by the process, and some are simply unable to navigate it.

This report presents cases in which young people were compelled to continue a pregnancy against their wishes because they were unable to comply with the PNA law or navigate judicial bypass, or because their parents interfered in their decision and prevented them from accessing abortion care. For example, Dr. Amber Truehart, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Chicago, shared the story of a 14-year-old she treated during labor and delivery who became pregnant after she was raped by her sister’s boyfriend. Her patient considered abortion but was so daunted by parental notification and the judicial bypass process that she ultimately continued an unwanted pregnancy resulting from rape and gave birth, at great risk to her own health. “She had preeclampsia. She had all the things that very young mothers are at risk for. She was in the hospital for a prolonged period of time, and her baby was in the NICU [neonatal intensive care unit].”

The report also includes cases of young people who felt compelled to involve unsupportive parents or adult family members in their abortion decisions because of the PNA law. Providers said they saw parents insult young people, refuse to pay the extra cost for a young person to have sedation during a procedural abortion, or leave them at the clinic without a ride home. In the most devastating cases, parental notification can place young people in physical danger. Dr. Erin King explained, “I see it in cases where a patient has come to us and said, ‘I notified my parents,’ or another adult living in the house that complies with the law, ‘and now because of that, I am scared about going home after this procedure.’”

Even with extraordinary legal and healthcare professionals available to offer support at a moment’s notice, forced parental involvement and the judicial bypass process can delay abortion care, sometimes quite significantly. A 2020 research study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health based on analysis of data collected by the ACLU of Illinois in 2017 and 2018 found that the judicial bypass process added, on average, nearly a week to young people’s abortion-seeking timeline in Illinois. The time elapsed between first contact with the ACLU’s Judicial Bypass Coordination Project and the young person’s court hearing ranged from 0 to 27 days.

In some cases, the delays caused by going through the judicial bypass process left young people ineligible for medication abortion, a noninvasive method available only up to the tenth week of pregnancy. Delays also required some patients to have multiple appointments over consecutive days to complete their abortion care.

Several providers said they had treated patients who delayed abortion care until they turned 18 to avoid notifying a parent or going through judicial bypass. A social worker with Planned Parenthood of Illinois shared that she counseled an 18-year-old patient who had traveled more than two hours to the clinic to receive a medication abortion. When she arrived at the clinic, she learned she was four days beyond the gestational cutoff for medical abortion. “She waited until that point because she was waiting until she was 18 years old to not have to tell her parents. She didn’t know judicial bypass was an option. She then had to travel 2 hours home and will in turn have to travel [another] 2 hours one way to an in-clinic procedure appointment.”

Nearly everyone interviewed for this report said young people expressed or demonstrated fear, anxiety, and stress around having to appear before a judge in order to be able to obtain abortion care. One young person who went through judicial bypass wrote in an anonymous survey that the hearing was “very stressful and nerve-wracking.” Attorney Stephanie Kraft Sheley said, “I had a client who was sitting there basically holding her breath waiting to see what the judge would say. … Her family situation was difficult.” When her request for a judicial waiver was granted, “She just broke down crying while the judge was still writing the order,” the attorney said.

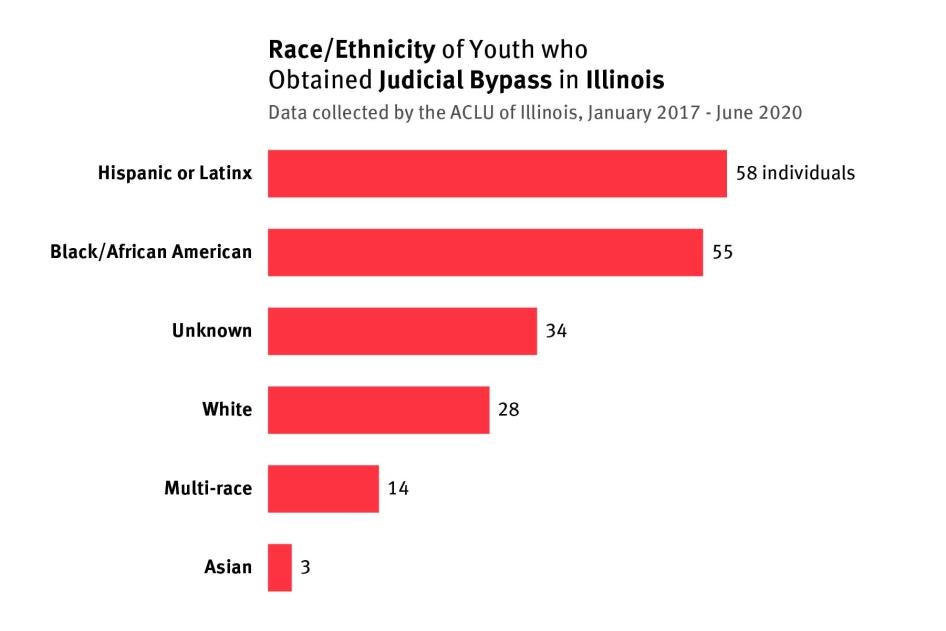

Several interviewees also commented on judicial bypass in the larger context of young people’s impressions of and experiences with court as places where people go after wrongdoing or being accused of committing crimes. Attorney Leah Bruno explained, “These young women are required to go to court, appear before a judge, and be sworn in at the beginning of a hearing in the very same way they hear about [happening in a criminal trial]…. So many of these young women have to sneak out of school and classes to do this. It’s all the wrong messaging. They are taking responsibility for their lives but being made to feel like they should be penalized for it.” The majority of young people who have gone through judicial bypass in recent years are Black, Indigenous and other young people of color, according to data collected by the ACLU of Illinois, which may influence their perceptions of and reactions to the legal system.

Forcing young people who choose not to involve a parent in their abortion decision to go through the judicial bypass process risks exposing them to a loss of confidentiality. Though not a frequent occurrence, young people pursuing judicial bypass have been found out or exposed. Retired Judge Susan Fox Gillis explained, “Adding what I believe is an unnecessary step of coming to court just makes it that much more difficult for her [to get abortion care], and that much more likely she’ll be found out [along the way]. If she has a fear of being found out and it’s legitimate, we’re putting her at risk.”

To avoid the spread of Covid-19, since mid-March 2020 Illinois courts have held judicial bypass hearings remotely, using an online platform. Experts said online hearings have eased logistical barriers for some young people. For others, however, the virtual hearings and the circumstances caused by the pandemic heightened risks around their confidentiality and safety since many young people can only rarely leave their homes due to Covid-19 restrictions and precautions. Emily Werth, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Illinois, explained, “Now we don’t have to get them to court. But a parent may be in the house, and could knock on the door, or come in at any moment. Some clients don’t have confidentiality in their homes, and if they have to go somewhere else, how will they get there, especially now with people not going out as much [because of the risk of Covid-19].”

Many interviewees—including lawyers, healthcare providers, and others—expressed concern that young people without parental support, and overwhelmed by or unable to navigate judicial bypass, may turn to unsafe abortion methods. “One client told me before she found out about the bypass project, she first tried an herbal [abortion] remedy she got off the internet,” one attorney said. This young person did not experience any harm from taking the herbal remedy, but it also did not induce abortion. “The people I think who are most affected by this law are the ones who never make it through our doors,” said Amy Whitaker, medical director of Planned Parenthood of Illinois.

The text of the 1995 Parental Notice of Abortion Act stated that the Illinois General Assembly’s purpose in enacting the law was “to further and protect the best interests of an unemancipated minor.” This report confirms what decades of research in other states have already shown: forced parental involvement is not in a young person’s best interests and can carry deeply harmful and life-altering consequences. As Hannah, an 18-year-old organizer with the Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health (ICAH), explained: “Forcing someone to tell their parents, it isn’t going to help. If someone can tell their parents, they will, because it’s so much simpler. The only people [PNA] really affects are the people it hurts.” Legislators should repeal PNA and enable young people in Illinois to make the best decisions for themselves regarding their sexual and reproductive health care.

Recommendations

To the Illinois General Assembly

- Repeal the Parental Notice of Abortion Act of 1995 as a matter of urgency and ensure that young people under 18 can access abortion care without being forced to involve a parent or other adult family member in their decision-making.

To the Illinois Department of Public Health

- Implement public information and awareness-raising campaigns that address stigma around abortion and around adolescent sexuality. Ensure such campaigns make clear that young people under 18 have the right to access a range of sexual and reproductive health services without parental involvement, while ensuring such campaigns also seek to reduce the disproportionate impact lack of access to health care and information can have on Black, Indigenous, and other young people of color.

Methodology

This report is a collaboration between Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Illinois. The report’s findings are based on in-depth interviews and research conducted by Human Rights Watch in 2020, as well as analysis of data and other information collected by the ACLU of Illinois between 2017 and 2020.

Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth interviews for this report between February and December 2020. We interviewed 12 healthcare providers and social workers who provide reproductive health care to young people under the age of 18; nine attorneys with experience representing young people seeking a waiver of parental notice of abortion (“judicial bypass”); one retired judge who previously presided over judicial bypass hearings in Illinois; four volunteers who provide young people with information regarding Illinois’ parental notice of abortion law; and 11 advocates, including 10 young people ages 18 to 27 involved in reproductive justice advocacy in Illinois. In total, we spoke with 37 people for this report.

A few interviews were carried out in person in Chicago, Illinois in February 2020. After February 2020, Human Rights Watch did not conduct any in-person interviews for this report given travel restrictions and our duty of care to prevent the spread of Covid-19. Human Rights Watch identified interviewees with the assistance of the ACLU of Illinois, other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), advocates, and service providers.

All interviews were conducted in English. In nearly all cases, Human Rights Watch held interviews individually and in private, though in a few instances, Human Rights Watch spoke to interviewees in pairs or in a small group.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be collected and used. Human Rights Watch assured participants that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions, without any negative consequences. All interviewees provided verbal informed consent to participate.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered topics related to sexual and reproductive health and rights, as well as access to information and services, centered on the experiences of young people under 18 seeking abortion care in Illinois. Most interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. Care was taken with all interviewees to minimize the risk that recounting difficult or traumatic experiences could lead to distress or further trauma. Human Rights Watch did not provide anyone with compensation or other incentives for participating. Some of Human Rights Watch’s organizational partners offered participants small stipends, consistent with their organizations’ policies related to research participation.

The names of some interviewees have been changed to protect their privacy and safety; real names were used only in cases where the interviewees preferred it and believed there was no risk to having their names published.

The report also incorporates information collected by the ACLU of Illinois from and about young people seeking judicial bypass. Since 2013, the ACLU of Illinois has operated a Judicial Bypass Coordination Project (JBCP) that provides information about the state’s parental notice of abortion law and the judicial bypass process and offers free legal assistance in judicial bypass proceedings. Beginning in January 2017, attorneys working with the JBCP began asking each client represented at a judicial bypass hearing for their permission to use de-identified (anonymized) information about their experiences for public education and/or research.[1] Some clients gave permission to the ACLU of Illinois to use their information for both purposes. Some gave permission to have their information used for only one of the two purposes. Others declined to participate.

Between January 2017 and August 2020, 182 clients gave the ACLU of Illinois permission to use de-identified versions of their stories for public education. ACLU of Illinois staff attorneys wrote short summaries of those 182 cases in narrative form and shared them with Human Rights Watch. Some of the narratives are included in this report.

In parallel, the ACLU of Illinois partnered with researchers at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) to develop a process for systematic data collection related to the experiences of young people seeking judicial bypass in Illinois. The ACLU of Illinois and UCSF researchers developed a standardized set of questions related to young people’s characteristics and experiences with judicial bypass, including age, race, stage of pregnancy, distance traveled to get to court and to an abortion clinic, reasons for seeking abortion without parental involvement, and other information. Attorneys working with the young people who consented to participate collected data through phone or in-person conversations.[2] Between January 2017 and June 2020, 192 young people in total gave the ACLU of Illinois permission to use de-identified data about them for research purposes, while 47 young people declined to share their information for research purposes. The ACLU of Illinois compiled the data and shared it with Human Rights Watch, and Human Rights Watch analyzed the data to produce statistics presented in this report.

Despite our strong interest in hearing from young people about the impacts of Illinois’ parental notification law, Human Rights Watch did not seek to speak directly with young people who went through judicial bypass. The ACLU of Illinois and Human Rights Watch determined we could not adequately mitigate the risks to young people’s privacy and safety that would be generated by asking young people to participate in interviews. Instead, the ACLU of Illinois shared with several young people the JBCP assisted in the judicial bypass process a short, anonymous online survey with two open-ended questions about their experiences (referred to throughout the report as “an anonymous survey”).[3] Attorneys working on the JBCP determined on a case-by-case basis whether it would be safe and appropriate to ask clients if they would like to receive the survey. Attorneys reached out to those clients within a few days of them receiving abortion care, explained the purpose of the survey and how the information could be used, and if the young people consented, sent them a link to the survey. Eleven young people chose to respond to the anonymous survey before final updates were made to this report, and the ACLU of Illinois shared the responses with Human Rights Watch.

Terminology

In this report, Human Rights Watch and the ACLU of Illinois use the terms “youth” and “young people” to refer to anyone under the age of 18. We use these terms for two reasons: 1) to affirm the autonomy and maturity of people under 18 to make the best decisions for themselves regarding their sexual and reproductive health care, and 2) to be inclusive of everyone who can become pregnant, including those who identify as cisgender females as well as those who are transgender or gender non-binary. However, where quoting interviewees, research studies, international law, or other sources directly, we have not changed the terminology used.

Throughout this report, we use the gender-neutral and inclusive pronouns “they” and “them” to describe young people. When referring to a specific person, we use that person’s individual pronouns.

We use “Black, Indigenous and other young people of color” to describe individuals and communities who may identify as Black or African-American; Hispanic, Latina, or Latinx of any race; Asian or Pacific Islander; North African or Middle Eastern; Indigenous; or multiracial. We use this terminology to be inclusive of a range of racial and ethnic identities and to bring visibility to the differential impacts of systemic racism and the criminal legal system on Black and Indigenous communities in the United States. Again, where quoting interviewees or other sources directly, we have not changed the terminology used.

In this report, we describe two methods of abortion: medical abortion and procedural abortion. Medical abortion—also known as medication abortion—is a way to end a pregnancy by taking medication, typically a combination of mifepristone (which stops a pregnancy from growing) and misoprostol (which induces abortion by softening and opening the cervix and causing uterine contractions to expel pregnancy tissue). Procedural abortion refers to various methods performed in a clinical setting to end a pregnancy and remove tissue from the uterus.[4] Both methods are highly safe and effective, though medical abortion is only available in Illinois until the tenth week of pregnancy.

I. Background

According to the Illinois Department of Public Health, about 1,000 young people under 18 who reside in Illinois have abortions in the state each year.[5] Illinois is one of 37 US states mandating parental involvement for young people under 18 seeking abortion care.[6] Abortion is the only type of pregnancy-related health care for which young people in Illinois are required to involve their parents, even though it is safer than continuing a pregnancy or childbirth.[7] Young people under 18 can access contraceptive methods to prevent pregnancy, decide to continue a pregnancy, access prenatal care, make decisions around labor and delivery, or consent to a caesarean section without involving a parent.[8] In Illinois, youth under 18 with children of their own can make autonomous decisions about their children’s health care, or can choose to place a child for adoption without any requirement of parental involvement.[9]

The Parental Notice of Abortion Act

Illinois’ Parental Notice of Abortion Act (PNA) of 1995 states that in order to provide an abortion for a young person under 18, a healthcare provider must notify an “adult family member” of the patient at least 48 hours in advance.[10] Under the law, only a parent, grandparent, step-parent living in the home, or other legal guardian over the age of 21 qualifies as one of the adult family members who may be notified.[11]

The law applies to anyone under 18 who has not been married or emancipated under the Emancipation of Minors Act, though there are certain exceptions.[12] Notice is not required in the event of a medical emergency or if the young person declares in writing that they are a victim of sexual abuse, neglect, or physical abuse by an adult family member.[13] If a young person utilizes the exception for survivors of abuse or neglect, the healthcare provider is mandated to report the abuse or neglect to the Illinois Department of Children and Families (DCFS).[14]

There is no exception in the law for youth who have already been pregnant or given birth: young people who are already parenting are still required to notify a qualifying adult of their abortion decision, unless they are married or meet one of the other narrow exceptions.

Under the law, the 48 hours advance notice is not required if the patient under 18 is accompanied by a qualifying adult family member at the point of care, or if the qualifying family member has waived notice in writing.[15] Otherwise, providers must give notice by telephone to the qualifying adult family member 48 hours before an abortion. If the adult family member cannot be reached in person or by telephone after “a reasonable effort,” the law specifies that providers may give notice by certified mail to a last known address.[16]

The Judicial Bypass Process

Young people under 18 who do not want to involve one of these specific adult family members in their abortion decision may seek permission from a judge to obtain an abortion without notification through a “judicial bypass” process. To grant a waiver of notice, a judge must find either 1) that the young person is sufficiently mature and well enough informed to decide intelligently whether to have an abortion, or 2) that notification to a qualifying adult family member under the law is not in their best interests.[17]

Under state law, any young person, whether or not they reside in Illinois, may petition any circuit court in the state for a waiver of the notice requirement.[18] Young people have the right to be represented by a court-appointed attorney and to have a guardian ad litem.[19] To protect the privacy of young people, all court proceedings must be confidential and all documents related to court proceedings must be sealed.[20] The court is required to rule on petitions for waiver of notice within 48 hours of filing, unless the young person or their attorney requests additional time. The court does not charge any fees for the process.[21]

The bypass process in Illinois is governed by federal constitutional standards established by the US Supreme Court in its 1979 Bellotti v. Baird decision. In Bellotti, the Supreme Court reviewed a Massachusetts parental consent law and affirmed that young people under 18 have a constitutional right to seek abortion. The Court held that a state may require parental involvement for abortion for those under 18, but that “it also must provide an alternative procedure whereby authorization for the abortion [without parental involvement] can be obtained.” The Court articulated a set of minimum standards for this alternative process, including that young people must have an opportunity to demonstrate that they are mature and well enough informed to make an abortion decision without parental involvement or that an abortion without parental involvement is in their best interests, and that the process should be confidential and expedited.[22]

Parental Consent vs. Parental NotificationIllinois state law mandates only parental notification, not parental consent, meaning a parent does not need to provide explicit permission for a young person to access care. However, experts interviewed for this report explained that in practice, for many young people, there is no distinction between parental notification and parental consent. When parents are in a position to withhold financial support, restrict young people’s movement or access to communication or transportation, or threaten life-altering consequences, they can effectively block young people’s access to abortion care even if the law requires only notice and not consent. |

History of Forced Parental Involvement in Illinois

Before the Parental Notice of Abortion Act of 1995 passed, Illinois had previously enacted three other parental involvement laws. The ACLU of Illinois challenged those laws in federal court, and they were never enforced.[23] The ACLU of Illinois also challenged the 1995 law in federal court. The court issued an injunction to prevent the 1995 law from taking effect because there was no appeals process, as required under Bellotti v. Baird, for the law to pass constitutional muster. That injunction remained in force for over a decade.

When the Illinois Supreme Court finally issued the necessary rules to provide for an appeals process in 2006, the state went back to federal court to get the injunction removed. The federal court ultimately ruled in favor of the state in 2009 and dissolved the injunction.[24] However, the ACLU of Illinois once again filed litigation, this time in Illinois state court, arguing that the law was unconstitutional under the state constitution’s due process and privacy clauses. Between 2009 and 2013, the law remained enjoined due to the state constitutional challenge. In 2013, the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the law, and for the first time, mandatory parental involvement for abortion went into effect for young people in the state.[25]

The ACLU of Illinois’ Judicial Bypass Coordination Project

Since 2013, the ACLU of Illinois has operated a Judicial Bypass Coordination Project (JBCP) that provides information about the state’s parental notice of abortion law and the judicial bypass process and offers free legal assistance in judicial bypass proceedings.[26]

The JBCP was designed to be a comprehensive resource for young people navigating the PNA law and is largely staffed by trained volunteers. It has a public website; a free, confidential hotline that young people can call, text, or email for information; and a network of pro bono attorneys prepared to represent young people in judicial bypass proceedings across the state.

More than 1,000 people have contacted the JBCP for help since it launched in 2013, and the project’s network of attorneys has represented more than 500 young people who went through the judicial bypass process between August 2013 and December 2020. The petition for waiver of notice has been granted in nearly every case the JBCP handled in that time.

Abortion Access in the Midwestern United States

Illinois is surrounded by states with harsh abortion restrictions. “All the states around Illinois have restricted access,” explained Terry Cosgrove, a longtime reproductive rights advocate with Personal PAC, a nonpartisan political action committee. “We’re the donut hole in the middle.”[27] For example, all the surrounding states (Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin) mandate parental involvement for a young person under 18 to have an abortion.[28] Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri and Wisconsin also mandate that patients must wait between 18 and 72 hours after receiving counseling before getting an abortion.[29] Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, and Wisconsin require the counseling to happen in person, forcing people to make at least two trips to a clinic to access abortion care.[30] In Iowa, Indiana, and Wisconsin, a patient must undergo a state-mandated ultrasound before an abortion.[31] Missouri currently has only one abortion clinic in the entire state, which has seen a dramatic decrease in patients seeking abortion care due to very restrictive and burdensome state laws.[32]

Advocates in Illinois have fought for years to reform state laws to safeguard sexual and reproductive health and rights. The Reproductive Health Act, signed into law in June 2019, affirmed that every person has the right to choose abortion, among other reproductive health care, and repealed several outdated restrictions on abortion access.[33] On the day he signed the bill into law, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker said, “I promised that Illinois would become a national leader in protecting reproductive rights. Illinois is demonstrating what it means to affirm the rights of individuals to make the most personal and fundamental decisions of their lives no matter their income level, no matter their race, ethnicity or religion.”[34]

However, the state’s parental notice of abortion law remains one of the main barriers to reproductive health care access in the state. As Dr. Erin King, an obstetrician-gynecologist and executive director of Hope Clinic for Women, explained:

Any law that puts additional barriers in front of a patient getting to a provider for abortion care is detrimental to them. Patients have a lot of barriers that they face to access abortion, regardless of where they’re coming from. Illinois tends to have less barriers, which makes it a place where patients can come and access care without having to worry about waiting periods, counseling mandates, ultrasound… The one thing people in Illinois still face is [parental notice of abortion] if they are a minor.[35]

II. Why Some Young People Do Not Involve Parents in Abortion Decisions

Most adolescents… are wise enough to make these decisions for themselves. There are a great deal of people who are lucky enough to have a parent or guardian whom they’re comfortable discussing this with, but there is a large portion of these patients who are not, and it really does pose a barrier to those patients to accessing care in a timely manner. It’s one more hurdle for them to overcome.[36]

—Hillary McLaren, obstetrician-gynecologist, December 3, 2020

Decades of public health research has shown that most young people under 18 voluntarily involve a parent or another trusted adult in their abortion decision, even if the law does not require it.[37] Dr. Erin King, an obstetrician-gynecologist and executive director of Hope Clinic for Women, analyzed data on young people seeking abortion care at her clinic before and after Illinois’ parental notification law went into effect: “We know that prior to this law going into effect, over 85 percent of minors were involving a parent anyway. Patients who feel like involving a parent is helpful in their decision-making were already doing that without the law.”[38] Research in Illinois and other states has shown that young people who do not involve a parent in their abortion decision often seek support from other trusted adults in their lives.[39]

Young people who do not involve a parent in their abortion decisions have many reasons. According to healthcare providers, attorneys, and others interviewed by Human Rights Watch, some pregnant young people believe notifying a parent or adult family member of their abortion decision would lead to abuse, being kicked out of the home, alienation from their families or other deterioration of family relationships, or being forced to continue a pregnancy against their wishes. These fears are often based on observing the lived experience of a sibling or other family member, or explicit statements or threats from parents.

A volunteer attorney who has represented at least 20 young people in judicial bypass cases said, “In almost every case I’ve experienced, the young person had some concern that a parent will cut them off financially, emotionally, or [notifying the parent would cause] major disruption to the relationship.” He said his clients had carefully and critically weighed the risks they would face by involving a parent: “For many of them they’ve literally been told by their parent this is what will happen. ‘You better not get pregnant or this will happen.’ A couple clients had seen it happen to a sibling.”[40]

In some cases, young people in these circumstances are able to navigate the judicial bypass system. Others opt to notify a parent, even when it is not in their best interests, and suffer whatever consequences that may bring. Others simply do not access abortion care and continue unwanted pregnancies against their wishes.

The ACLU of Illinois collected data on the reasons why young people pursued judicial bypass with the assistance of the JBCP between January 2017 and June 2020, summarized in Table 1 below.[41] Most young people cited multiple reasons for not involving a parent. Among 192 participants who agreed to share their data, 40 percent said they were concerned about being forced to continue the pregnancy, 40 percent had concerns about being kicked out of their house or cut off financially, and 30 percent feared harming the relationship with their families. Seventeen percent had minimal or no contact with one or both of their parents, for example because of parental death or ambiguous legal guardianship situations. A smaller subset of participants had fears of physical or emotional abuse (9 percent) or had concerns due to difficult or unstable family situations (11 percent), such as a family member’s illness or incarceration. Below, we present examples of such cases.

Table 1. Reasons Youth Seek Judicial Bypass |

||

|

Number of participants who cited reason |

Percentage of participants who cited reason |

|

|

Fear of being forced to continue the pregnancy |

77 |

40% |

|

Fear of being kicked out of the house or cut off financially |

76 |

40% |

|

Fear of straining or ruining family relationships |

57 |

30% |

|

No or minimal relationship with one or both parents |

32 |

17% |

|

Unstable or difficult family circumstances |

22 |

11% |

|

Fear of physical or emotional abuse |

17 |

9% |

Fear of Abuse

Some young people do not involve a parent or other qualifying adult in their abortion decision because they fear emotional or physical abuse, often where there has been a history of abuse in the family. Stephanie Kraft Sheley, a volunteer attorney with the JBCP who represents young people outside of the Chicago area, estimated that she had handled about nine bypass cases since 2017. “I’ve definitely had clients express fear that they would be physically harmed because they had been hit in the past, and they felt like [a pregnancy and abortion decision] would also be grounds for that in their household.”[42]

The ACLU of Illinois represented “Sarah” (not her real name), a young person in a judicial bypass hearing whose parents were “very religious and strict” and whose father had hit her after he found out that she had a boyfriend. Sarah “feared for her physical safety if her parents learned that she was pregnant and planning to have an abortion.”[43]

Katy Phipps, director of business operations at Family Planning Associates, regularly provides options counseling and emotional support to pregnant youth under age 18. In an interview, she fought back tears as she described assisting a young person from an immigrant family who obtained a judicial bypass because she was certain that if her family members learned of her pregnancy and abortion decision, “they’d send her back to her home country and she would face an honor killing.”[44] Phipps was not sure what ultimately happened to the young person after her abortion, but said it was “one of the cases that will probably always stay with us.” Dr. Allison Cowett, an obstetrician-gynecologist and co-medical director at Family Planning Associates who was also involved in this young person’s care, described the case as “heart-wrenching”: “She felt strongly that if her [family] knew she was having sex, she’d be seriously harmed. She was worried for her personal safety.”[45] Phipps added, “I’ll never forget that situation. I’ll never forget her. She just was so hopeful. ‘I know these are my goals. This is what I want. This is not the right time for me.’”[46]

For young people who have faced abuse, the judicial bypass process does not offer any additional pathway to support. Emily Werth, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Illinois, explained that healthcare providers are trained to identify abuse and offer support—whether their patients under 18 involve an adult family member in their abortion decision or pursue judicial bypass. “Abortion providers have procedures to identify patients of any age who may be in unsafe situations and to offer resources and support,” Werth said. “They are mandated to report suspected abuse or neglect [of those under 18] to [the Department of Children and Family Services]. The judges who preside over judicial bypass hearings, on the other hand, have no such expertise or training to assist youth in unsafe home situations.”[47]

Fear of Being Kicked Out

Many young people do not involve a parent in their abortion decision because they fear they will be kicked out of the home and/or isolated financially. For example, Dr. Rebecca Commito, an obstetrician-gynecologist in Chicago, described counseling a young person whose mother was not part of her life, and who lived with her father but “didn’t have a supportive or affirming relationship with him.” Dr. Commito explained that the young person’s father had threatened to throw her out of the house if she became pregnant: “It wasn’t safe for her to share [her abortion decision] with her dad. She said if she did, she wouldn’t have a place to live…. It wouldn’t be a safe environment to be in if she disclosed a pregnancy, let alone abortion.”[48]

Dr. Allison Cowett provided abortion care to a 16-year-old who chose to go through the judicial bypass process. The young person told her:

My mother is very strict with me. If she knows I’m pregnant, she’ll definitely throw me out of the house…. I talked to my boyfriend about moving in with him, but he lives with his mother and several younger siblings, and he sleeps on the couch. He already sleeps on the couch, where am I going to sleep? On the floor?[49]

Trisha Rich, a volunteer attorney with the JBCP who estimated that she had represented about 20 youth seeking judicial bypass since 2013, assisted a young person who was born in the United States but whose parents were immigrants. “Her parents had told her and her sister both that if they ever got pregnant, they’d send them [away to the parents’ country of origin]. When her older sister did get pregnant, they sent her [away] and told her she couldn’t come back until she was married. The sister didn’t return for years and years and years.” Rich said that when her client became pregnant, she explained clearly, “My parents said they’ll send me [away], and they’re serious. … I don’t even know anyone there.”[50]

Another attorney said he had a client who had been kicked out of her home because of a prior pregnancy scare. When his client actually became pregnant, the attorney said, “She had [already] experienced the harm that she now knew was going to come [if she notified her parents].”[51]

Ashley Olson, another volunteer attorney with the JBCP, represented a young person with a similar story: “She had an older sibling who had gotten pregnant as a teenager. When her parents found out about her older sibling being pregnant, that sibling was kicked out of the house…. That was the big reason … [my client] did not want to tell her parents.”[52]

Fear of Being Forced to Continue an Unwanted Pregnancy

Many people interviewed for this report said young people under 18 expressed fears that their parents would force them to continue an unwanted pregnancy against their wishes if notified of the young person’s abortion decision.

One social worker who regularly counsels pregnant young people, including those who pursue judicial bypass, said the reason most young people she encountered chose judicial bypass was because “their parents are religious and would never accept them getting an abortion.”[53] “They’re afraid that the choice will be taken away by their parent,” another social worker explained.[54]

The ACLU of Illinois represented “Avery” (not her real name), a 16-year-old client who worked three days a week as a cashier and was responsible for caring for six younger siblings: “[She] had an older sister who had gotten pregnant as a teenager, and [her] parents had forced her to continue the pregnancy but then kicked her out of their home.” When Avery learned she was pregnant, “she feared that the same thing would happen to her.”[55]

“Julia,” another ACLU of Illinois client, had a similar experience. She was a 16-year-old sophomore in high school with plans to attend college after graduation. When Julia learned she was pregnant, “she knew she could not tell her parents about the pregnancy. In the past, Julia’s parents had told her that if she became pregnant, they would force her to continue the pregnancy and drop out of school to get a job and care for the baby.”[56]

Fear of Harming Family Relationships

Another common fear articulated by pregnant youth, according to the people interviewed for this report, is that involving a parent in their abortion decision will strain, deteriorate, or ruin familial relationships. Leah Bruno, an attorney who has represented around 50 youth in bypass hearings since 2013, said young people with these kinds of concerns generally “fall into two camps”: 1) those who hope to maintain largely positive relationships with their parents; and 2) those who have “challenging relationships already” and do not want to risk destabilizing those relationships further.[57]

For example, Dr. Allison Cowett provided abortion care for a young person who was being raised by a single father and strongly felt that involving him in her abortion decision would “be very straining” on their otherwise good relationship. “She did not feel like she could tell her father about this.” Dr. Cowett’s patient had ample support in her abortion decision from other adults in her life, but she had to pursue judicial bypass because none of them met the definition of a qualifying adult family member under Illinois’ PNA law.[58]

In contrast, Leah Bruno described working with a young person who had “a very tumultuous relationship” with her only living parent. The client “was trying to preserve what small amount of harmony there could be by terminating the pregnancy without involving her [parent]…. It was clear she was responsible for herself while still living in her [parent’s] home…. Financially she was taking care of herself. She was 16. And it was clear that she had been taking care of herself for a long period of time already.”[59]

Unstable Family Situations

In some circumstances, young people do not involve parents because their families are experiencing unstable or difficult situations, and they fear burdening already-struggling parents.

Dr. Amber Truehart, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Chicago, provided abortion care to a young person who sought judicial bypass because her father was “not in the picture” and her mother lived in another state and was confronting health, legal, and socio-economic challenges:

Her mom had coronavirus at the time and didn’t have stable housing. [My patient] was not even sure where [her mom] was…. Her mom was already dealing with a lot of other stuff. … She didn’t want to add one more thing to what her mom was already dealing with. She thought her mom would view her differently afterwards when she returned home.[60]

Jill Adams, an attorney who has represented young people in bypass hearings outside of the Chicago area, described a case in which her client’s mother had died months earlier and the client had moved around to different family members’ homes since her mother’s death. “[At some point after] her mother died, she went to live with her father, but things weren’t going so well. She didn’t have that strong of a relationship with her dad…. He gave her a place to stay, but there was no closeness.”[61]

No or Minimal Contact with a Parent

Among the young people harmed by PNA are those without any parent or other qualifying adult family member in their lives, or those who have only minimal contact with their parents.

A social worker recalled counseling an undocumented young person who had been separated from her family in an immigration detention facility when they entered the United States: “She didn’t speak any English. She was terrified. The pregnancy was a result of a very violent sexual assault.” The young person wanted an abortion, but providers were unable to reach her parents because they had been separated. The social worker explained: “It was a real mess. Ultimately, … she got a judicial bypass, [but] it was a heartbreaking one. There were so many complications and barriers.”[62]

Dr. Rebecca Commito, an obstetrician-gynecologist in Chicago who provides abortion care for young people, explained:

The vast majority of young people have an adult figure they feel safe disclosing their abortion decision to and [making] part of that process. But there is a significant and important handful of people who live outside of a traditional family unit for survival or because of whatever happened in their family. They may not logistically be able to get in touch with a family member that follows the legislative criteria. The law doesn’t mirror their family.

Dr. Commito noted that young people who are not able to involve a parent in their abortion decision often “seek out other mature adults for support. An older sister, a partner’s family members, an aunt, a cousin. Families look different. Young people find a support person in another way.”[63]

The ACLU of Illinois represented “Stella” (not her real name), a 17-year-old client who lived with her aunt because her father had died, and “she had a volatile relationship with her mother, who had sometimes been violent toward [her].” When Stella found out she was pregnant, she talked with her aunt about her options, but she “was scared that her mother would become violent if she found out about the pregnancy.” However, Stella’s aunt could not be the one to receive official notice of the abortion under Illinois’ law because the aunt did not have legal guardianship, so Stella had to go through the judicial bypass process.[64]

Gail Eisenberg, a volunteer attorney with the JBCP, described the situation of a young person she represented in a judicial bypass hearing: “I had one client whose mother was in jail. Her father wasn’t in the picture. There were no other adult family members [that qualify] under the [Parental Notice of Abortion] Act that she could notify. She didn’t want to create any more stress on her mother in jail than she needed to.”[65]

III. Barriers to Accessing Judicial Bypass

Under state law, young people who wish to obtain an abortion without notifying one of the qualifying adult family members can go through a judicial bypass process, as described above, to demonstrate to a judge that 1) they are sufficiently mature and well enough informed to make an abortion decision without parental involvement, and/or that 2) parental involvement is not in their best interests.[66] Despite the strenuous efforts of a compassionate and dedicated network of care providers, attorneys, and volunteers, young people face formidable logistical hurdles throughout the process, particularly around accessing information, communicating safely, scheduling hearings, and securing transportation. Many young people are understandably overwhelmed by the process, and some are unable to navigate it.

A volunteer with the Judicial Bypass Coordination Project’s free, confidential hotline for young people seeking information and assistance regarding PNA summarized some of the challenges: “The bulk of the calls I get are young women who are completely resolute in their decisions. They have taken home pregnancy tests, they have gone to a clinic, received options counseling, are clear that they are terminating their pregnancy. This is just the next box they have to check. But they are freaked out because it’s a bizarre process to have to go through. The judicial bypass process is so strange. When in your life would you think, ‘I went to the doctor, and they told me I have to get a lawyer.’ It’s a bizarre process to have to go through to get medical care. … Then you need to figure out logistics, what day you’ll miss school, [how to establish] plausible deniability with parents about where you are.”[67]

Challenges Accessing Information and Confusion about PNA

Accessing the judicial bypass process requires young people to find safe ways to obtain information about the availability of this option in the first place. “It takes knowing who to ask, what to ask, knowing where to go to get access to resources,” said Hannah Dismer, the education and research coordinator at Hope Clinic for Women. “For very low-income young people, for young people under the age of 16, … there are significant barriers to even having the resources or knowing where to turn for these kinds of things. We’ve heard from people who wanted to pursue judicial bypass, and then we never heard from them again. …. We don’t know what happens to them [in those situations].”[68]

Valentina, an 18-year-old activist with the Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health (ICAH), said many young people she knew had no idea what judicial bypass was: “Not everyone has that information. It’s not widely known.” Valentina said her high school sex education class was “abstinence-based” and did not even mention abortion, much less judicial bypass. She wondered, “Who knows how many young people … actually know that the ACLU is there for them for judicial bypass?”[69]

Yasmine Ramachandra, a 23-year-old organizer with the National Asian Pacific American Women's Forum (NAPAWF) Chicago Chapter, supported a friend who was worried she might be pregnant during her senior year of high school. “That’s when I first heard about PNA,” she said. Yasmine and her friend are both Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) and Yasmine explained that even though her friend knew she wanted an abortion, she could not involve her parents. They learned judicial bypass was an option but could not find resources about navigating the process. “We were trying to pull together money to see if we could pay someone to help my friend go to court [for a judicial bypass]. We were thinking, ‘What are the chances we’d even be able to get to court? How do we talk to a judge about this? Why do I have to explain to someone else that I want this to happen? They’re going to hear such a personal thing.’ As we were reaching out to clinics and trying to talk it through, as we were panicking, she got a negative pregnancy test [but] it really scared her.”[70]

When young people do learn that judicial bypass is even an option, many are very intimidated. One young person who was granted a judicial waiver wrote in response to an anonymous survey, “It was scary at first not knowing what to expect.” Another wrote, “The process seemed really overwhelming at first.”[71]

Dr. Amber Truehart, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Chicago, counseled a young person in the foster system about the PNA law, and said her patient was deeply distressed about navigating the process:

She didn’t even know who she was supposed to [notify] because of how complicated her social situation was…. She was very overwhelmed by the process. She was crying on the phone, saying ‘It’s never going to happen if I have to do all these things. It’s never going to happen.’ She had irregular periods, so she wasn’t sure how far along she was. As she thought of having to do these things [the bypass process entailed], [when] she knew she had limited alone time, limited phone time. … It was really hard to get her to trust that if we got her the right resources, we’d figure out her situation.[72]

Volunteers with the JBCP’s confidential hotline said young people often expressed confusion around the process.[73] One volunteer explained, “It’s a lot to juggle mentally… The mental gymnastics of the timeline and figuring out ‘If I’m this many weeks along [in a pregnancy], my procedure is scheduled for this day, I need a bypass ruling by this day.’ They are under a lot of stress, and they definitely convey that stress and anxiety, not about the procedure or the decision itself, but about the process.”[74]

“One of the biggest things we see is confusion with what the law means,” said Dr. Erin King, an obstetrician-gynecologist and executive director of Hope Clinic for Women. Dr. King said her patients sometimes thought the law required parental consent, rather than parental notification, or that two parents had to be involved. She also recounted a situation where a young person struggled to understand how to comply with the law for several weeks:

This patient was 15 and living with an aunt who wasn’t her legal guardian. Her mom was still her legal guardian but not a trusted adult in her life and was hard to notify because she often didn’t know where her mom was. [The young person] was living in a state nearby, a five- or six-hour drive away…. It took a good four to six weeks of her trying to manage this herself, when she finally did get in touch with someone at the clinic who had more information to help her comply with the law without having direct contact with her mom…. We were able to see her for an abortion, but it was a good six weeks after she had started trying to [pursue an abortion].[75]

Gail Eisenberg, a volunteer attorney with the JBCP, worked with a young person who was under the impression she needed a parent’s involvement and a judicial waiver in order to get abortion care. Eisenberg was preparing the young person for the court hearing when her client disclosed that her mother was involved and supported her abortion decision. “She was under the impression that it was an absolute requirement [for all young people] to get a judicial bypass,” even if they had a parent involved. “She was going through this whole process for no reason.”[76]

Safe Communication Challenges

Once young people know judicial bypass is an option and understand the steps involved, they have to connect with an attorney, speak with the attorney over the phone to prepare for a judicial hearing, and receive counseling on options from a trained provider. Young people living with their parents must go through each of these steps without their parents finding out and triggering the harmful response(s) they are seeking to avoid, and each of these conversations or points of connection risks exposing them to a loss of confidentiality.

One young person who went through judicial bypass shared this reflection on the process in response to an anonymous survey: “The most difficult part was trying to find moments alone to talk to each person.”[77] Volunteers and attorneys with the ACLU’s Judicial Bypass Coordination Project described talking with young people who spoke to them in hushed tones from inside a closet, hastily hung up the phone, or rushed through a conversation when a parent returned home unexpectedly for fear of being exposed.[78] “I’ve had calls drop in the middle of a conversation because parents walked in,” said one social worker with Planned Parenthood of Illinois.[79]

Retired Judge Susan Fox Gillis represented a young person seeking a judicial bypass, and said her client had to leave the house to talk on the phone in order to prepare for her court hearing: “During our second phone call, she was walking around the block. It was nighttime and dark. I was concerned about her safety.”[80]

“It’s a lot of logistics for a young person to be dealing with,” said Dr. Rebecca Commito, an obstetrician-gynecologist in Chicago. “It weighs on them having to get on the phone, talk to someone in a private place, worry about their own safety. I have young people calling me from school in between [class] periods, trying to figure out when they can leave school safely to talk to me…. It’s a heaviness to have to go through so many hoops in an already tumultuous environment.”[81]

Some parents closely monitor young people’s phones and other communications. Attorney Leah Bruno, for example, represented a client in a judicial bypass hearing who could only communicate with her when she went to her brother’s house: “Even though she had her own phone, she was concerned that her parents would look at her phone or see her talking on the phone and overhear her conversation. … She said her parents could see any texts that she was receiving or sending.”[82]

Scheduling and Transportation Challenges

Another highly challenging part of the judicial bypass process for many young people is scheduling a hearing at court and travelling to and from the hearing. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, hearings were held exclusively in person during regular business hours, and young people had to secure transportation to the courthouse and arrange time away from school, work, or other obligations without their parents being alerted. Many young people under 18 do not drive or do not have access to a car and have to find safe and reliable transportation both to court and to a clinic for their abortion care.

“It’s really difficult and complicated,” explained attorney Trisha Rich, who has represented about 20 young people in judicial bypass hearings. “They have to skip school without anyone noticing, get all the way to the courthouse, and get around court without being noticed.”[83]

Stephanie Kraft Sheley, also an attorney, said that it was an enormous challenge for some of her clients “just getting to court when the court is open and available to hear the case, and getting to the clinic at times when the clinic is open and providing service,” hours which often coincide with the times young people are expected to be in school. “Certain schools if you don’t show up, they have an automated message that goes out to the parents that the child isn’t in school, so [it is a challenge] trying to get around that, and make sure the parents are not alerted. Some [parents] have trackers on [young people’s] cell phones, so they have to turn off their cell phones when they are traveling, which makes connecting at court difficult.”[84]

The challenges can be especially formidable for young people traveling long distances to access the judicial bypass process and abortion care. A 2020 research study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health based on the experiences of those who went through judicial bypass in Illinois in 2017 and 2018 found that young people sometimes traveled a considerable distance to the courthouse for their hearing. The authors explained:

Distances traveled varied significantly by state and region of residence. Although minors living in the City of Chicago traveled an average of 9.0 miles, those from Illinois, but outside the Chicago region, traveled an average of 33.3 miles, and those from out-of-state traveled 130.8 miles.[85]

Katherine Davis, a volunteer with the Judicial Bypass Coordination Project’s confidential hotline, said young people often expressed a range of concerns as they learned about the process: “One of the biggest concerns is how quickly it can be done. The concerns of trying to find a way to get transportation to a courthouse. Potentially missing school. Fears of parents being notified of that [missing school]. Attendance. Because court closes, the latest you can go is 4 p.m., and it’s not open on the weekends. You really have to strategize.” She said a lot of callers “are really terrified of a parent finding out” as a result.[86]

Challenges during the Covid-19 Pandemic

To avoid the spread of Covid-19, Illinois courts have held judicial bypass hearings remotely, using an online platform, since mid-March 2020. Experts said these online hearings have eased logistical barriers for some young people but heightened risks around confidentiality and safety for others, since many young people can only rarely leave the home due to Covid-19 restrictions and precautions.

Emily Werth, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Illinois, said initially there were challenges scheduling virtual hearings and ensuring court orders reached clinics in a timely fashion. Once a system for online hearings was in place, transportation became less of a barrier for clients, but new concerns emerged around confidentiality. Werth commented:

[In the past], once we got [our clients] to court, the only people allowed in were the attorney, the client, a court reporter, and a judge. Once they got themselves to court—which was really tricky—we knew how the process would go, we could guarantee confidentiality. Now we don’t have to get them to court. But a parent may be in the house, and could knock on the door, or come in at any moment. Some clients don’t have confidentiality in their homes, and if they have to go somewhere else, how will they get there? ... especially now with people not going out as much [because of the risk of Covid-19].[87]

Attorneys and healthcare providers said some young people lacked access to reliable internet for online hearings. “Not every minor has a laptop with Wi-Fi that they can use to get on Zoom for a call with a judge,” said Dr. Erin King.[88] Sarah Bazzetta, a licensed clinical social worker at Planned Parenthood of Illinois, said they worked with a young person who didn’t have access to the internet and had to go to another location for her online hearing.[89] Attorney Stephanie Kraft Sheley represented a client who only had internet access on a cell phone, and her data usage was closely monitored by her parents, so she could not participate in an online video hearing without a spike in data usage being noticed by her parents.[90]

Another attorney, Gail Eisenberg, expressed concern with online hearings requiring log-in information or appearing in browser histories and potentially exposing her clients to loss of confidentiality in that way. Eisenberg also said she feared technical difficulties or other aspects of online hearings complicating young people’s ability to demonstrate their maturity and credibility to a judge. “Eye contact is a big part for some of these judges in their assessment of a young woman’s maturity, and they often will put that in their orders, ‘She made eye contact.’ And eye contact on [video platforms] is difficult. Even the most studied person can be confused when looking at a judge versus looking at the camera.”[91]

Young People Who Fall Through the Cracks

The people I think who are most affected by this law are the ones who never make it through our doors.

—Amy Whitaker, medical director, Planned Parenthood of Illinois, February 13, 2020

Nearly everyone interviewed for this report expressed concern about young people who never learn judicial bypass is an option or are ultimately unable to follow through with the process. A social worker described how difficult it is to capture the experiences of those who do not pursue or complete the process:

The people that go through judicial bypass, they’re the most resourceful minors there are. … What we don’t know is how many people never get that far. Who are pregnant and end up telling parents anyway, and we then don’t know what those consequences might be. They may continue their pregnancy, may come in for abortion and have told their parents but are dealing with a lot of crap from the parent, things like that.[92]

Leah Bruno, an attorney who estimated she had represented about 50 young people in judicial bypass proceedings in recent years, said:

I have had clients that decided they didn’t want to proceed with the bypass. They would prefer to deal with the fallout of telling their parents as opposed to coming downtown and going to court…. [We don’t know] if that meant they decided to see the pregnancy through until term, or decided to tell their parents and still got an abortion. It’s impossible to say what ultimately happened. I have clients that I talk to [once or twice] and never hear from again.[93]

Many interviewees—including lawyers, healthcare providers, and others—expressed concern that young people without parental support, and overwhelmed by or unable to navigate judicial bypass, may turn to unsafe abortion methods. “One client told me before she found out about the bypass project, she first tried an herbal [abortion] remedy she got off the internet,” one attorney told Human Rights Watch. This young person did not experience any harm from taking the herbal remedy, but it also did not induce abortion.[94] Human Rights Watch has extensively documented how laws and policies that restrict access to abortion threaten the health and lives of pregnant people, delay and obstruct access to health care, and drive abortion underground, making it less safe.[95]

Dr. Erin King emphasized how difficult it was for anyone to access abortion care, even without the obstacles forced parental involvement and judicial bypass create:

It’s hard for anyone to get online, make an appointment, get money together, come into the clinic, take time off from school or work…. [Parental notification] is just one more step. It’s one more thing. When you have ten barriers to overcome, it can ultimately break the system and you can’t get to where you’re going. …You get everything in line and then you have to get past that last hurdle.[96]

IV. The Harmful Consequences of the Parental Notice of Abortion Act and the Judicial Bypass Process

Research by Human Rights Watch and the ACLU of Illinois showed that the Illinois Parental Notice of Abortion Act (PNA) harms young people in numerous ways, whether they choose to notify a qualifying adult family member or to go through judicial bypass. Young people who are unable to pursue judicial bypass or find the process too daunting may be compelled to continue unwanted pregnancies or pushed to involve unsupportive or even abusive parents who threaten their safety, interfere in their decision-making, or punish or humiliate them.

And even when young people are able to navigate the judicial bypass process, it delays their access to abortion care. Appearing before a judge to justify an abortion decision is stressful and emotionally taxing for many young people, and even traumatizing for some. Participating in the process risks violating their confidentiality. Though the overwhelming majority of petitions for judicial waivers have been granted since the PNA law went into effect, the process still has devastating effects on many young people who must go through it.

Forced Continuation of Unwanted Pregnancy

Human Rights Watch received reports of cases in which young people were compelled to continue a pregnancy against their wishes because they were unable to comply with the PNA law or navigate judicial bypass, or because their parents interfered in their decision and prevented them from accessing abortion care.

One social worker told Human Rights Watch that she tried to help a young person access abortion care after PNA went into effect. Her parents were extremely anti-abortion, and they knew that she was pregnant, but when they received notice that she planned to have an abortion, they prevented her from leaving the home: “At that point, her parents took away her car keys. We were asking does she have anyone who could take her, a boyfriend or friend, but her parents threatened to report her as a runaway and that the police would bring her back home…. She said, ‘There’s no way I’m going to be able to come in,’ and that was horrible. ‘My parents are going to make me place the child up for adoption. I don’t want to do that.’ … [Her parents] weren’t letting her out of their sight. She couldn’t go anywhere. She was a prisoner in her own home…. This person was forced to continue her pregnancy… Her autonomy was completely removed, taken away from her.” The provider was unsure about the ultimate outcome of the young person’s pregnancy, but she was unable to access abortion care at their facility.[97]

Dr. Amber Truehart, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Chicago, shared the story of a 14-year-old she treated during labor and delivery who became pregnant after she was raped by her sister’s boyfriend. Her patient was so daunted by parental notification and the judicial bypass process that she continued an unwanted pregnancy resulting from rape and gave birth, at great risk to her own health. “She had preeclampsia. She had all the things that very young mothers are at risk for. She was in the hospital for a prolonged period of time, and her baby was in the NICU [neonatal intensive care unit].”[98]

Ricardo, an 18-year-old organizer with the Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health (ICAH), described the story of a young person he knows who became pregnant before turning 18: “She was scared and didn’t want to continue the pregnancy. She wanted to go off to college.” Ricardo was unsure about whether the young person knew judicial bypass was an option. When she told her parents she wanted an abortion, “her parents told her ‘you’re not welcome back in this family if you [end the pregnancy]. … We don’t believe in abortion.’” Ultimately, the young person continued the pregnancy and chose to parent, but “if it was up to her, she wouldn’t have continued the pregnancy.”[99]

Nearly everyone interviewed for this report expressed concern for the unknown number of young people who were unable to navigate or access judicial bypass and therefore continued unwanted pregnancies against their wishes. Dr. Erin King, an obstetrician-gynecologist and executive director of Hope Clinic for Women, said “I think of all the people who probably started down that path and never made it to the end and stayed pregnant when they don’t want to be.”

Unsupportive or Abusive Parents

Several healthcare providers interviewed for this report said some of their patients felt compelled to involve unsupportive parents or adult family members in their abortion decisions because of the PNA law.[100] Providers saw parents belittle, humiliate, or punish their patients while they received abortion care, even if the parents did not ultimately interfere with the young person’s abortion decision. Sarah Bazzetta, a licensed clinical social worker at Planned Parenthood of Illinois, said, “I’ve seen [angry] parents coming in. Being insulting. Saying ‘She’s just sleeping around.’”[101] Another social worker said she’d seen parents refuse to pay the extra cost for a young person to have sedation during a procedural abortion.[102]

Dr. Amber Truehart, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Chicago, said she provided abortion care to a young person whose mother refused to give her a ride home afterward. “We had a mom who left her daughter there [at the hospital] …. She said, ‘You can get yourself home. Figure it out.’” The young person had agreed to notify her mother in order to comply with the law, even though her mother did not support her decision.[103]

Dr. Hillary McLaren described seeing similar interactions between young people and their parents while providing abortion care for patients under 18: “All it does having an unsupportive family member [involved in a young person’s abortion decision] is just layer on guilt and shame and judgement.”[104]