Introduction

Human Rights Watch writes in advance of the 82nd session of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (“the Committee”) relating to Turkey’s (“the Government”) compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (“the Convention”) in its eighth periodic report.

Human Rights Watch recalls that, in its 2016 review of Turkey’s seventh periodic report, the Committee leveled robust criticism at the Turkish authorities for implementation failures with respect to legislation concerning the protection of women from violence. In reference to Turkey’s implementation of protective orders and injunctions (in the scope of Turkey’s Law to Protect the Family and Prevent Violence against Women, no. 6284), the Committee noted in its concluding observations that: “…protection orders are rarely implemented and are insufficiently monitored, with such failure often resulting in prolonged gender-based violence against women or the killing of the women concerned.”[1]

In its 2016 review, the Committee therefore recommended that the Turkish authorities: “[v]igorously monitor protection orders and sanction their violation, and investigate and hold law enforcement officials and judiciary personnel accountable for failure to register complaints and issue and enforce protection orders.”[2]

Lack of effective enforcement of protective and preventive orders

Relevant to the Committee’s above-mentioned observation and recommendation, Human Rights Watch shares in this submission the findings of its latest research on Turkey published in a report entitled “Combatting Domestic Violence in Turkey: The Deadly Impact of Failure to Protect” (submitted as an appendix). [3] Human Rights Watch’s research shows continuing problems with the Government’s efforts to effectively protect women from domestic violence, prevent its recurrence, and hold perpetrators to account. The research focused on the use of protective and, in particular, preventive (restraining) cautionary orders issued by courts and law enforcement officials under Law 6284.

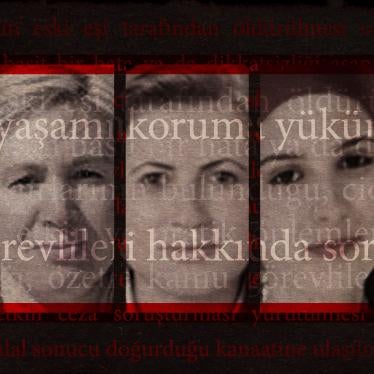

The findings are based on interviews with victims of domestic violence and their lawyers, police officers, judges and prosecutors, and include detailed examination of 18 cases – 17 of them from the period 2019-2022 – where women lodged complaints to the police or the prosecutor and had secured preventive orders barring the perpetrator from contact with the victim, or protective measures such as shelter accommodation. In six of the cases examined, the woman was killed by the abusive current or former husband or partner despite having secured preventive (restraining) orders and therefore being known to the authorities to be at risk. In other cases examined, women secured multiple preventive orders but abusers repeatedly breached orders barring any contact and the cycle of abuse continued. The research also examined cases where preventive orders were effective.

Human Rights Watch’s main findings include the following:

- While courts and police are issuing an increasing number of protective and preventive orders from year to year, there are still major concerns about a lack of effective enforcement;

- Courts often issue preventive (restraining) orders for short periods, in some cases just weeks or a month, irrespective of the persistent risk and threat of violence; In particular, there is no indication that orders are routinely issued to protect women for the pre-trial period, when the alleged abuser is being prosecuted;

- In practice, the authorities fail to undertake effective risk assessments or monitor the effectiveness of the orders, leaving survivors of domestic violence at risk of ongoing, and at times deadly, abuse;

- Some perpetrators breach the terms of preventive orders without penalty but the authorities are not recording these breaches or providing transparent data on the incidence of breaches;

- When courts convict perpetrators of domestic violence for crimes such as intentional injury, threats and insults, the penalties are often issued late and are too little to constitute an effective deterrent to prevent further abuse;

- While perpetrators of femicides are generally punished, the Turkish authorities do not routinely investigate or hold public officials to account for failure to exercise due diligence in protecting victims of domestic violence they know to be at risk;

- Poor data collection prevents authorities and the public from having a solid grasp on the scale of domestic violence in Turkey or the gaps in implementing protection which contribute to ongoing risks for victims;

- There is no data publicly available about the work of the provincial Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers under the Ministry of Family and Social Services, responsible for overseeing and monitoring the implementation of protective and preventive orders;

- Survivors of violence, families of victims, or their lawyers often resort to appeals via social media, and sometimes in print media or television, in an effort to trigger action by the authorities. While successful in some cases, the need to resort to such tactics is an indictment of the authorities’ failure to provide protection or to respond adequately to the risks victims face.

The government’s own data shows a lack of effective enforcement of protective and preventive orders. The Interior Ministry’s figures presented to a parliamentary commission on violence against women demonstrate that in around 8.5 percent of cases of women killed between 2016 and 2021, the woman had been granted an ongoing protective or preventive order at the time of her death. In 2021, the Interior Ministry recorded that 38 of the 307 women killed were under protection, the highest number over the previous five-year period for which figures are recorded.[4]

In its 2016 review, the Committee (as stated above) recommended that the Government take steps to hold public officials to account for failures to ensure effective protection of women. There are few signs that the Government has taken such steps. Human Rights Watch considers that its latest research demonstrates the need for clear processes for investigating and holding to account public authorities in cases where they have not exercised due diligence in preventing and protecting victims of domestic violence.

In this respect, a judgment of Turkey’s Constitutional Court published in December 2021 breaks new ground. In the case of T.A. (no. 2017/32972), the court identified a catalogue of state failures amounting to violation of a woman’s right to life in substantive and procedural terms. The court determined that public officials, prosecutors, and judges had failed to take the necessary steps to protect a woman who had lodged multiple complaints with the authorities before she was killed by her former husband. The decision is consistent with the case law of the European Court of Human Rights.

Withdrawal from the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (the Istanbul Convention)

Human Rights Watch would like to emphasize that Turkey’s 2021 withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention triggered alarm among domestic women’s rights groups and civil society, as well as internationally. As the Committee is aware, the move has raised deep concerns about the Government’s commitment to protecting women from violence and, more broadly, to promoting gender equality and combatting discrimination.[5] The Government has made efforts to repudiate suggestions that withdrawal undermines efforts to combat violence against women and, in its reply to the Committee’s List of Issues, asserts that it has the necessary domestic legal infrastructure in place. Moreover, it insists that its commitment to combatting violence against women is supported by its introduction of a human rights action plan, a fourth five-year national action plan to combat violence against women, and a parliamentary commission examining the causes of violence against women, among other measures.[6]

Human Rights Watch’s latest research demonstrates, however, that regardless of action plans and other recent government policies and legislation, there are deep, ongoing challenges regarding effective implementation and enforcement of protection measures. It is imperative that Turkey pursue further steps to combat domestic violence and all other forms of violence against women to comply with its obligations under the Convention.

Recommendations

The CEDAW Committee should press the Government of Turkey to carry out the following recommendations:

Recommit to and comply with international law on combatting violence against women and domestic violence

- Reverse Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention and promptly reaffirm Turkey’s commitment to eliminating all forms of violence against women at the national, regional, and international levels by rejoining the convention.

- Ensure full implementation of all measures required to prevent further violations identified in the European Court of Human Rights Opuz v. Turkey case and related cases under enhanced supervision before the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers;

Strengthen the application of preventive and protective orders under Law No. 6284

- Ensure that despite withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, police units, prosecutors, and courts across Turkey strengthen their commitment to applying protective and preventive orders under Law No. 6284 in response to reports of domestic violence and violence against women; and that the orders are applied and served promptly, are commensurate with the level of risk carefully assessed and are tailored to the needs of the victim, relying on the full range of measures available;

- Ensure that it is mandatory for police units to inform all victims of their rights under the law, including the details of the protective and preventive orders available to them and their right to legal aid, including through provision of interpreters for victims who do not speak Turkish or are from disadvantaged groups (including foreign nationals who are asylum seekers or other migrants, including Syrians with temporary protection status),

- Ensure that police, prosecutors and family courts take an inclusive approach to all victims of domestic violence and offer the same protection to all, avoiding any discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity;

- Establish systems that clarify roles and responsibilities and ensure full and effective coordination among different agencies operating under the Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Justice, and Ministry of Family and Social Services. Ensure each takes full responsibility for their role in (i) applying protective and preventive orders according to detailed risk assessments; (ii) monitoring their ongoing implementation; and (iii) maintaining follow-up communication with victims in a timely, survivor-centered, and responsive manner to ensure their continuing safety;

- Ensure that legal aid through Bar Associations is accessible to all domestic violence victims.

Strengthen the implementation of preventive orders through sanctions for breaches

- Ensure that detention is imposed as a sanction for breaches of protective and preventive orders;

- Continue to develop and extend the use of electronic tags for perpetrators of domestic violence who breach protective and preventive orders;

- Provide clear guidelines to prosecutors and courts that repeated breaches of protective and preventive orders may constitute grounds for suspects to be placed in pretrial detention in the context of a criminal investigation on the grounds that they pose a threat to the safety of the victim and witnesses;

- Ensure that the Ministry of Family and Social Services conducts a full evaluation and publishes detailed information and statistics about the performance of provincial Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers in overseeing the implementation of protective and preventive orders. The ministry should consult on the substance of any plan to reform or restructure the centers with civil society groups focused on combatting violence against women and the women’s rights commissions and centers of provincial bar associations, as well as with other relevant ministries.

Strengthen steps to ensure justice and redress for victims

- Ensure that prosecutors conduct thorough, timely, and effective investigations into allegations of domestic violence and violence against women and girls capable of leading to the prosecution of perpetrators and their conviction on charges appropriate to the severity of the crime in a fair trial.

- Ensure that prosecutors can secure court decisions on preventive orders against alleged perpetrators of domestic violence that will ensure the safety of victims for the duration of a criminal investigation, while maintaining each process as separate and independent so as not to undermine the presumption of innocence in criminal law;

- The Ministry of Justice should develop guidelines to discourage courts from issuing decisions of non-pronouncement of verdict (a form of suspended sentence) in cases where perpetrators have repeatedly breached preventive orders issued against them;

- Ensure that, in instances of alleged failure by the relevant authorities to take timely and effective steps to protect victims who have sought their protection, the officials in question are subject to administrative investigation and if found at fault, disciplinary action;

- In accordance with the Constitutional Court’s decision in the T.A. application (no. 2017/32972) and the European Court of Human Rights Opuz v. Turkey decision and other relevant caselaw, ensure that the authorities are held to account through criminal investigation leading to the possibility of prosecution and conviction for failures to exercise due diligence in providing protection to victims that contribute to or result in harm to the victim or threats to life;

- Ensure that settlement processes do not become a means by which perpetrators of violence can avoid being held accountable for their crimes and that, in cases of domestic violence where preventive and protective orders have been issued, there is no attempt at that stage to resort to a settlement process which would bring together the parties in breach of the terms of the orders;

- Ensure that those conducting the settlement process are properly trained to understand the particular complexity of domestic violence cases, have a duty to make it clear to victims that settlement is never mandatory and should not be means to encourage victims to consent to impunity for perpetrators.

Strengthen the collection of data to enable measurement of the effectiveness of protective and preventive orders issued under Law No. 6284

- Ensure that the Ministry of Justice coordinates the creation of an effective system for recording all breaches of protective and preventive orders (via the UYAP online judicial data system), categorizing the form of breach and the response to the breach, and publish full data regarding the breaches

Strengthen the collection and publication of data to support justice and redress for victims:

- Ensure that the Ministry of Justice Department of Judicial Statistics supplies detailed disaggregated data about the outcome of criminal investigations, prosecutions, convictions, and acquittals of perpetrators of violence against women and domestic violence under all articles of the Turkish Penal Code, including cases of physical assault, rape and sexual violence (including marital rape), verbal and online or other harassment, threats, insults, stalking, attacks on property, and ensure that data relating to all aspects of the authorities’ measures to protect victims from domestic violence, including the implementation of preventive and protective cautionary orders, breaches of such orders, measures taken against perpetrators in response to breaches, and reasons for decisions to prosecute perpetrators or not is made publicly available on a regular basis.

Increase the capacity, resources and support to combatting domestic violence and violence against women

- Provide police units dealing with domestic violence and violence against women with sufficient capacity and resources to respond to violence against women in line with international best practice standards, and provide courts focused on issuing protective and preventive orders and prosecutorial authorities with increased capacity to reduce their caseload per judge and to enable them to take time to interview victims in person where appropriate.

Increase cooperation with civil society organizations with expertise in working on domestic violence and violence against women

- Ensure effective and ongoing consultation during legislative drafting and policy planning between the ministries of family and social services, justice, and interior and civil society organizations with recognized expertise in the areas of domestic violence and violence against women;

- Cease judicial harassment of civil society organizations, including any judicial proceedings against the We Will Stop Femicide Platform Association seeking to close down the association for “violating law and morality”.

[1] CEDAW, Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of Turkey, 25 July 2016, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N16/233/44/PDF/N1623344.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 18, 2022), para. 32/b.

[2] Ibid, paragraph 33/c.

[3] Human Rights Watch, “Combatting Domestic Violence in Turkey: the deadly impact of failure to protect,” May 26, 2022: Combatting Domestic Violence in Turkey: The Deadly Impact of Failure to Protect | HRW

[4] Interior Ministry numbers are cited in the final report by the Parliamentary Enquiry Commission Investigating all aspects of the reasons for violence against women… (TBMM Kadına Yönelik Şiddetin Sebeplerinin Tüm Yönleriyle Araştırılarak Alınması Gereken Tedbirlerin Belirlenmesi Amacıyla Kurulan Meclis Araştırması Komisyonu), March 6, 2022: see https://www5.tbmm.gov.tr//sirasayi/donem27/yil01/ss315.pdf (accessed March 13, 2022), p.219-20.

[5] See, for example: “Council of Europe leaders react to Turkey’s announced withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention,” Council of Europe, March 21, 2021, https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/council-of-europe-leaders-react-to-turkey-s-announced-withdrawal-from-the-istanbul-conventi-1 (accessed May 18, 2022); “Turkey’s announced withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention endangers women’s rights,” Commissioner for Human Rights, March 22, 2021, https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/turkey-s-announced-withdrawal-from-the-istanbul-convention-endangers-women-s-rights (accessed May 18, 2022); “Turkey: Withdrawal from Istanbul Convention is a pushback against women’s rights, say human rights experts,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, March 23, 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/03/turkey-withdrawal-istanbul-convention-pushback-against-womens-rights-say?LangID=E&NewsID=26936 (accessed May 18, 2022); “UN women’s rights committee urges Turkey to reconsider withdrawal from Istanbul Convention as decision takes effect,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, July 1, 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/07/un-womens-rights-committee-urges-turkey-reconsider-withdrawal-istanbul?LangID=E&NewsID=27242 (accessed May 18, 2022); “Turkey: Statement by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell on Turkey’s withdrawal of the Istanbul Convention,” European Commission Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, March 20, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/news/turkey-statement-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-turkeys-withdrawal-istanbul-2021-03-20_en (accessed May 18, 2022).

[6] See CEDAW/C/TUR/RQ/8, “Replies of Turkey to the list of issues and questions in relation to its eighth period report,” February 22, 2022: N2226934.pdf (un.org).