According to the most recent official data, around four out of ten women in Turkey have suffered physical and/or sexual violence during their lives. Hundreds are murdered by their partners every year, even though in some cases they had reported their abusers to authorities more than once. In some cases, their deaths could possibly have been prevented, had the authorities made sure that restraining orders were respected, breaches punished, and perpetrators prosecuted, according to a new Human Rights Watch report, “Combatting Domestic Violence in Turkey: The Deadly Impact of Failure to Protect.” Birgit Schwarz speaks to Emma Sinclair-Webb, Europe and Central Asia Division associate director, about the Turkish state’s failure to provide effective protection from domestic violence, and what this means for victims.

How big of a problem is domestic violence in Turkey?

The most recent official government study found that close to 40 percent of women have suffered physical and/or sexual violence during their lives. We also see a high level of stalking. But data collection is generally poor and makes it difficult to provide an accurate picture of the scale of the problem today. Women’s rights groups and independent media regularly record hundreds of femicides every year. Most domestic violence cases only become visible once a woman goes to the police and lodges a complaint, or when women attempt to get a divorce. That’s when the violence often explodes.

Why is gender-based violence such a problem in Turkey?

The government’s approach to combatting violence against women is framed in paternalistic, conservative terms. The authorities see it as part of a national duty to protect women, whom they see as vulnerable and breakable, and to support the institution of the family. Turkey’s president is on record opposing gender equality and it has been written out of government policy. So while we are seeing government efforts to tackle violence against women, the government simultaneously undermines its own efforts by not seeing the fight against domestic violence as part of promoting women’s rights or ensuring gender equality.

The country’s withdrawal in 2021 from the Council of Europe’s convention designed to combat domestic violence, known as the Istanbul Convention, and which was opened for signature in Turkey, underscores this problem. You need public commitment to gender equality to address the root causes of domestic violence. Withdrawing from the convention means rejecting the international legal norms on gender equality and combatting gender discrimination. Also, Turkey has the lowest participation of women in the labor force among countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a grouping of more economically advanced countries. Economic dependence makes it more difficult for women to leave abusive relationships.

What protection exists for victims of domestic violence?

Under Turkey’s domestic violence law, women who are abused can apply to the police or the courts for preventive cautionary orders such as restraining orders, which can bar the perpetrator from approaching and contacting the victim. Victims are also entitled to apply for protective cautionary orders offering access to a shelter and other measures including financial assistance.

Perpetrators can be held in detention for short periods if they breach the terms of restraining orders or sometimes be required to wear an electronic tag in the event of repeated breaches. And Turkey’s parliament has recently passed a new law that makes stalking a crime punishable by six months to two years in prison.

However, while an increasing number of preventive and protective orders are handed out by the courts, there is an enormous problem with enforcing them and prosecuting abusers. We found that courts often issue cautionary orders for too short a period, and that breaches are not punished with detention. And when it comes to prosecuting domestic violence, courts tend not to put offenders in pretrial detention, even if there is evidence of interfering with the victim. Then months later the court might simply issue a fine or suspended sentence on condition that the defendant does not reoffend within five years. Also, the authorities are failing to undertake effective risk assessments and don’t ensure the orders are observed. This leaves domestic violence survivors at risk even when they have reported abuse.

What does this mean for abused women?

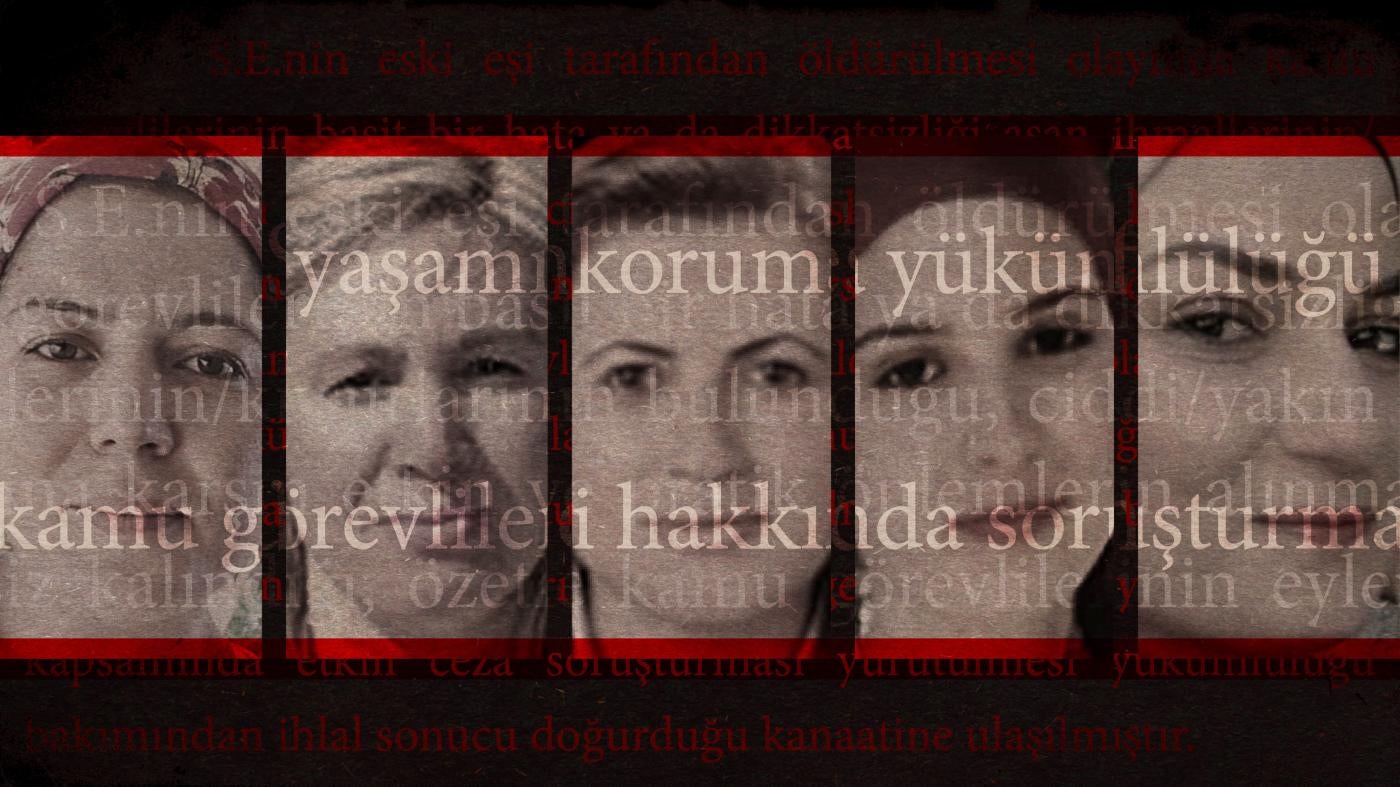

When the state fails to protect women, life becomes a torment. In six of the cases we examined, the women who suffered domestic violence were killed by their abusers. All had filed official complaints. Had the authorities looked at the patterns of violence and harassment that preceded the murders, the women’s deaths might have been prevented. Sadly, too many cases of domestic violence only come to light when it’s too late. The Interior Ministry recently revealed to a parliamentary commission that, in 2021, 38 of the 307 women killed had had a preventive order issued against the perpetrator.

What are some of the cases of killings that you documented?

Pelda Karaduman was abducted by her cousin when she was 12 years old. She gave birth to two children when she herself was still a child, before the cousin shot her dead at age 18. There were lots of opportunities for the authorities to bring her back to her family and prosecute the abuser. She was a minor, after all, when she had her children. And there was a long history of abuse. Yet none of these steps were taken.

Then there is the murder of Ayşe Tuba Arslan, which made headlines in Turkey. Ayşe complained 23 times about her husband’s abusive behavior. She divorced him. He killed her. Only three weeks before Ayşe’s death, her husband was prosecuted for publicly threatening to “shoot and kill” her. The sentence was suspended on condition that he not repeat the offence. The authorities should have known better.

Have officials been held to account for their role in failing to prevent these femicides?

While authorities have become better at prosecuting femicides and now routinely hand down life sentences to men who murder their partner, in the case of Pelda Karaduman, for instance, no public official, no court, no prosecutor has been investigated or faced disciplinary action for their role in failing to protect her. In Ayşe Tuba Arslan’s case, a criminal investigation into possible negligence by public officials ended in a decision not to prosecute. And a case filed by Ayşe’s parents against the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Family and Social Services for damages for having failed to protect their daughter was rejected. The verdict is being appealed.

Unless the courts, the police, and other officials understand how their own conduct contributes to women losing their lives, there will never be proper protection for domestic violence victims.

Have you come across cases where the protection worked?

Court orders can be effective. We found that the role of determined lawyers ready to follow up and push for perpetrators to be prosecuted was key. So is the role of women’s rights organizations, which have been instrumental in strengthening the legal rights of women in Turkey over many years. The authorities would be well advised to consult and work with these lawyers and organizations. Instead, these organizations are sidelined or under attack. The authorities have even started a closure case against the We Will Stop Femicide Platform Association, a vocal campaigning group, accusing it of “violating law and morality.”

What recourse do abused women have when the official system fails them?

One of the most striking things we have seen recently is that women or their lawyers have taken to social media when faced with official inaction. This has been highly effective, which is good. But it is also worrying that this kind of public naming and shaming is necessary before the authorities are spurred into action.

What can the Turkish government do to protect women better?

Turkish authorities are very keen to be seen to be taking resolute action, which is why more and more preventive and protective orders are being issued. But the authorities need to scrutinize if and how these orders are working. Government institutions need to do a lot more in terms of monitoring their own performance and coordinating their response. There needs to be more consistent data collection to be able to understand why lack of enforcement is so entrenched. Police and courts need to get better at risk assessment and at spotting the warning signs. And breaches of restraining orders need to be penalized much more resolutely. And lastly, the authorities’ failure to prevent femicides – even in cases of repeated incidents of violence –should be investigated and those responsible should be held to account.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.