Wu Yingjie, the Chinese Communist Party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region, recently visited Chamdo, in the province’s east, for the celebrations of the 70th anniversary of the town’s “liberation” – meaning the People’s Liberation Army’s defeat of the Tibetan army there in October 1950. In a speech summarizing Beijing’s current Tibet policy, Wu notably called for eradicating all influence of the Dalai Lama from Tibetan Buddhism inside Tibet “so that the believing masses distinguish religious devotion from everyday life, distinguish religious devotion from separatist sabotage, distinguish religious devotion from the 14th Dalai, and distinguish religious devotion from enjoying their present happy life.”

Under the Communist Party’s latest religion policies for Tibet, administered by official work teams stationed in monasteries, Buddhist monks and nuns are required to live up to “four standards.” Besides genuine proficiency in the Buddhist teachings, they must also be “politically reliable,” ready to “serve the masses,” and be “dependable during critical moments,” meaning potential outbreaks of dissent. Wu’s “four distinguishes,” however, apply to the Tibetan population at large, whom Party jargon calls “the believing masses.”

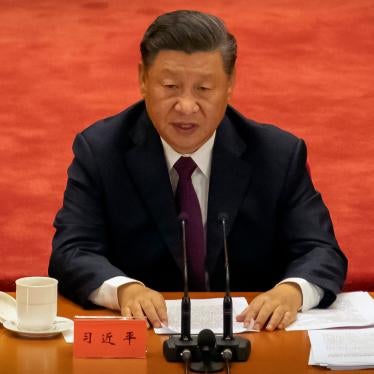

Criticism of religion is a current theme of compulsory political education in villages, neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces. The message is that Tibetans should value “the happy life they now enjoy,” rather than focusing on preparation for the next life, as prescribed by religion. This is referred to as “guiding people to take a rational view of religion,” especially the “wastefulness” of offerings and ceremonies, and the reminder that it is the Party and President Xi Jinping whom ordinary Tibetans have to thank for their “happy lives,” not the lamas.

Wu’s “four distinguishes” mean not just that ordinary Tibetan believers must reject their spiritual leader, but even that their religious beliefs must not affect their everyday lives or influence their social behavior. The Party maintains that its “freedom of religious belief” policy will never change, but these requirements stretch its credibility to the limit. What the authorities call “accommodating religion to socialist society” involves an increasing subordination of religious freedom to the shrill demands of a government that, 70 years after “liberation,” still sees the attitudes and beliefs of ordinary Tibetans more than ever as a threat to its dominance.