Rofhiwa Mlilo is a 40-year-old single mother who sells sex for a living in a small town in South Africa. Unlike the alternative of picking fruit on local farms, sex work provides her with enough money to support her two children.

Mlilo, whose name I have changed for her protection, would prefer if her job selling sex was protected by law so that she could be sure to make it home safely to her children every night. Instead, she lives in constant danger of being harassed, arrested, or detained by police. The police abuse forces her into the shadows, where sex workers often face violence from male solicitors and less protection against HIV.

South African authorities are compromising the safety and wellbeing of thousands of women like Mlilo by treating sex work as a crime, we and a partner group have found. But it doesn't have to be this way. Our findings give credence to a growing recognition around the world that decriminalizing sex work is an essential step toward gender equality.

We have researched illegal sex work in China, Tanzania, Cambodia, South Africa, and the United States, where workers are often forced to conduct business in dangerous back streets, parks, and abandoned buildings. Whether interviewing sex workers in wealthy US cities or small South African towns, we consistently find police abuse to be one of criminalization's main cruelties. Sex workers often face harassment, extortion, and rape, and vulnerability to violence—at the hands of both police officers and men who purport to be customers. Women tell us that because they cannot trust members of law enforcement, they are deterred from reporting attacks by men who pretend to be clients but who abuse, rape, and sometimes even try to kill them.

Sex workers have also told us that being arrested and detained by police has interrupted their access to health care, including essential HIV treatment. This is particularly dangerous in South Africa, which has the largest HIV epidemic in the world.

But South Africa is not the only nation whose policies put sex workers in danger. I see many similarities between the United States, my current home, and my native South Africa, where I grew up after apartheid and in the throes of the AIDS epidemic. Both are influential countries whose constitutions are relatively strong on human rights, but whose communities are plagued by endemic violence against women. Sex work is illegal in both countries. Nevada is the only US state where the exchange of sex for money is allowed.

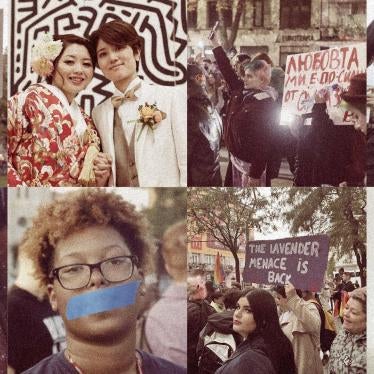

Fortunately, South Africa and the United States are both sites of growing movements to decriminalize sex work once and for all. US activists are gaining traction with a groundbreaking bill introduced in New York's legislature. In another sign of progress, Senator Kamala Harris recently went on record during her presidential campaign to support decriminalization. Meanwhile in South Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa indicated this year that he's open to rethinking laws that make sex work illegal.

In both countries, there is also the risk that half-measures could derail the road to progress. Politicians are increasingly drawn to the "Nordic model," which they see as a compromise between sex worker activists who want "decrim" and middle-class voters who think sex work should be banned. This model, first used in Sweden, makes buying sex illegal but does not prosecute the seller, the sex worker. It aims to end sex work by killing the demand for transactional sex.

But in practice, the "Nordic model" has a negative impact on sex workers. It makes it harder for sex workers to unionize, run their own brothels, open a bank account for their business, and find safe places to work. It also leaves in place the stigma around sex work that leaves so many women vulnerable to violence and police abuse.

As a South African who has lived through the end of apartheid and witnessed continuing inequities, I am not naïve. Decriminalization won't solve every problem for women like Mlilo, who turn to sex work to feed their children. But the fact remains that South Africa and the United States will be safer places for women once they stop undermining the autonomy and dignity of people who want to earn a living on their own terms.

Liesl Gerntholtz is acting program director at Human Rights Watch. The new report on sex workers was a joint effort between Human Rights Watch and the South Africa-based Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT).

The views expressed in this article are the author's own.