Sycamore, IL 60178

|

Letter

Submission to Illinois Supreme Court Commission on Pretrial Practices

June 26, 2019

Hon. Robbin J. Stuckert

Chief Judge, 23rd Judicial Circuit DeKalb County Courthouse

Chair, Supreme Court Commission on Pretrial Practices

133 W. State Street

Sycamore, IL 60178

Sycamore, IL 60178

Supreme Court Commission on Pretrial Practices

Pretrial Comment

AOIC Probation Division

3101 Old Jacksonville Road

Springfield, IL 62704

By post and email: Pretrialhearings@illinoiscourts.gov

Dear Commissioners,

Human Rights Watch is an international non-profit organization dedicated to investigating and reporting on human rights violations throughout the world, including in the United States.[1] Human Rights Watch has reported on violations in over 90 countries and, as a founding member of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, was a co-laureate of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997. Our US Program focuses on, among other things, human rights compliance within the criminal legal system.

Human Rights Watch has produced two major reports and many shorter pieces documenting the human rights concerns raised by the money bail system employed in nearly all US criminal courts and recommending reforms. The reports specifically highlighted the systems in New York[2] and California,[3] but the principle problems of money bail and pretrial incarceration apply similarly in other states, including Illinois.

In light of the commission’s exploration of pretrial reforms, we write today to share some of our findings and recommendations. We recommend Illinois adopt pretrial reforms that ameliorate the substantial harms of the money bail system by reducing pretrial detention overall while removing financial requirements for release. Human Rights Watch urges avoiding the use of risk assessment tools—that is, mathematical formulas to estimate the likelihood that an individual will commit some future misconduct—because they make recommendations based on statistical estimates and profiles rather than individualized evidence, they have inherent racial and class bias, and because they will not guarantee reductions in pretrial incarceration rates. Instead, pretrial reform should honor the presumption of innocence by greatly limiting who is eligible for pretrial incarceration in the first place, and by requiring individualized hearings with rigorous evaluations of evidence, procedural requirements, and standards of proof, before a court can order incarceration.

The Harms of Money Bail and Pretrial Incarceration

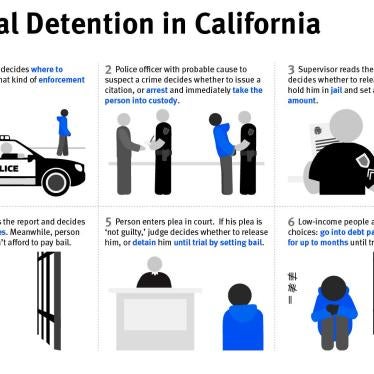

Unnecessary use of pretrial incarceration betrays the presumption of innocence, a fundamental guiding principle of the US legal system, by keeping people in jail who have not been convicted of a crime. Our California report documented that between 2011-2015, close to half-a-million people, were subject to felony arrests and held in pretrial detention, but never found to be guilty of any crime, an unjust punishment that cost taxpayers millions of dollars.[4] Poor people jailed pretrial, with bail set, face the miserable options of taking on heavy debt to pay bail, remaining in custody until their cases resolve, or pleading guilty to gain freedom sooner, regardless of actual guilt.

Human Rights Watch documented families losing homes, selling cars, and foregoing basic living necessities to afford bail.[5] People who stay in jail lose jobs, cannot care for their children or disabled relatives, miss needed health care, while suffering boredom, violence, disease and physical and mental anguish.[6] In California, according to Human Rights Watch’s analysis of data from six counties, the vast majority of people released from jail as “sentenced” on low-level felonies and misdemeanors were released before the earliest possible date they could have gone to trial. In other words, to assert their innocence at trial, they would have had to stay in jail longer than they did by pleading guilty.[7] Practitioners throughout the country, including Illinois, have told us that similar pressure to plead guilty exists in their jurisdictions that use money bail. Given the coercion inherent in this choice, convictions of innocent people are inevitable. The large-scale use of pretrial detention, resulting in pressured guilty pleas, damages the credibility of our criminal legal system.

These harms are more profound because they apply only to those too poor to pay bail, while the wealthy have the benefit of a system that honors the presumption of innocence.

Given the well-documented inequities of the money bail system, Human Rights Watch commends the many stakeholders in the Illinois courts and government who are taking serious steps to reform the way courts impose pretrial incarceration. However, we are concerned that these reforms will be derailed by reliance on risk assessment tools that influence who is imprisoned and who is released.

Risk Assessment Tools are a Dangerous, Unfair Substitute

The Illinois Supreme Court has released a policy statement indicating its intention to support the use of risk assessment tools for pretrial incarceration decision-making, as a foundation for a system that conforms to the presumption of innocence and provides due process through individualized decisions.[8] Human Rights Watch disagrees that these tools serve these objectives and strongly advises against their use in deciding the pretrial fates of accused people.[9]

Risk assessment tools used in the criminal legal system purport to estimate the statistical likelihood that a person will commit some misconduct (missing a court date or arrest for a new crime, in the case of pretrial prediction) in the future. They take discrete facts about the person, without providing individualized context for those facts, then compare that person to a large dataset of other people for whom the same discrete, non-contextualized facts exist. They then assign a likelihood of future misconduct by the person based on the percentages of successful or unsuccessful outcomes from the large dataset.

In other words, the tools make predictions that are used to determine freedom or imprisonment based on how other people have behaved in the past and statistical estimates, in other words, based on profiles. The criminal legal system, however, should ground decisions in an individual’s own actions, not those of other people. The lack of consideration of individual context leads to unjust outcomes. For example, the most commonly used tool, developed by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation (Arnold), scores past missed court dates against a person, but does not distinguish between situations, such as in when the person missed court due to illness and appeared the next day, as opposed to when a person deliberately leaves a jurisdiction to avoid prosecution. The same tool scores for “prior violent conviction” without distinguishing between a misdemeanor battery involving a push and an attack with a knife causing serious injury. It similarly scores for “prior felony conviction,” which can range from drug possession for personal use to murder.[10]

Despite their claims, the tools do not predict future crime. To the extent they predict anything, it is future arrest. While an individual’s behavior partly determines likelihood of arrest, police behavior is a significant determining factor. People living in over-policed communities or otherwise subject to aggressive policing face higher risk of arrest for the same behavior. For example, someone who illegally possesses a firearm in a community with a low police presence will have little risk of being stopped and searched, while someone in a highly policed community will have a high risk of stop, search and arrest. Historic and current racial and class bias in policing, including discrimination by individual officers, racial profiling and biased deployment patterns, strongly influences arrest results.[11] Nationally, white and black people use illicit drugs at roughly equal rates, but police arrest black people at substantially higher rates for these offenses.[12]

Risk assessment tools generally do not use race or economic class specifically in their formulas. However, they use other factors that stand as proxies for race and class, including arrest history, employment history, residential stability and education levels. This means that the profiles have a built-in bias, reflective of and amplifying the biases already existing in the criminal legal system and in US society as a whole.[13] While the tools may not be designed to be racist, because they rely on racially biased inputs, their outputs or recommendations will reflect that bias.[14] In addition, because of their claim to scientific objectivity, they may provide a veneer of legitimacy to that discrimination.

Risk assessment tools are often promoted as an effective mechanism to reduce pretrial incarceration, but, in fact, they can be used just as easily to increase incarceration. While New Jersey, which used the tools as part of a comprehensive set of recent pretrial reforms, has had significant reduction in pretrial incarceration rates,[15] Kentucky, which also uses the tools, has not.[16] In Lucas County, Ohio, implementation of the Arnold tool increased the rate of pretrial detention and increased the percentage of people pleading guilty on their first court appearance.[17] The scoring system of any risk assessment tool can be adjusted to fit more or less people into the various risk categories, thus allowing it to be manipulated to raise or lower the numbers of people released or detained. Santa Cruz County in California adjusted its tool’s “decision making framework” and doubled the number of people assigned to release with supervision.[18] If judges control the scoring system and implementation of the tools, as they did in Kentucky[19], given the effect of pretrial detention pressuring guilty pleas that move court calendars rapidly,[20] it is likely that risk assessment tools will not result in reductions in pretrial incarceration.

These inherent problems—decision-making based on non-contextual statistical predictions, racial and class bias, and subjectively adjustable scoring—are reason enough to reject use of the tools by a state seeking to implement an equitable system that respects the presumption of innocence. Additionally, the tools are not especially accurate[21] and rely on secretive formulas and data that makes it difficult, if not impossible, for defendants to understand how their scores were generated in order to challenge their recommendations.[22]

The tools run counter to basic principles undergirding the US legal system, including that each person should be judged as an individual. International human rights law protects an individual’s right to liberty from arbitrary curtailment, either through arbitrary laws or through arbitrary enforcement of the law.[23] The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has emphasized that pretrial custody decisions should not be made by reference to pre-set formulas, patterns or stereotypes, but, instead, must be grounded in reasoning that contains specific, individualized facts and circumstances justifying such detention.[24]

Pretrial Reform Without Risk Assessment

Human Rights Watch recommends reforming the pretrial detention system by eliminating or strictly limiting money bail, but without replacing it with risk assessment tools. New York state recently passed a law that requires release for people accused of most lower-level categories of crimes, while requiring hearings with improved procedural guarantees for those eligible for detention. [25] Community organizations and national advocacy groups are supporting a pretrial reform framework, called “Preserving the Presumption of Innocence,” which similarly favors release for lower-level categories of crimes, rigorous procedures for detention hearings for those eligible, and prohibition on the use of statistical prediction on risk assessment. [26] Human Rights Watch strongly supports this framework for reform. The city of Philadelphia recently changed policy to increase pretrial release, without relying on the tools, and found no significant increase in rates of new arrests or missed court appearances.[27]

Illinois has an opportunity to reform its pretrial system in a way that increases fairness and respect for the rights of pretrial defendants without sacrificing public safety. Risk assessment tools have been heavily marketed as a shortcut to that goal, but, by their inherent nature, they fail to deliver the required fairness and may simply replace one unjust system with another. The state can achieve reform by respecting the presumption of innocence and providing for pretrial incarceration only where there is concrete evidence, proven through an adequate court process, that an individual poses a serious and specific threat to others if they are released. Human Rights Watch recommends having strict rules requiring police to issue citations with orders to appear in court to people accused of misdemeanor and low-level, non-violent felonies, instead of arresting and jailing them. For people accused of more serious crimes, Human Rights Watch recommends that the release, detain, or bail decision be made following an adversarial hearing, with right to counsel, rules of evidence, an opportunity for both sides to present mitigating and aggravating evidence, a requirement that the prosecutor show sufficient evidence that the accused actually committed the crime, and high standards for showing specific, known danger if the accused is released, as opposed to relying on a statistical likelihood.

Sincerely,

John Raphling

Senior Researcher, US Program

Human Rights Watch

11500 W. Olympic Blvd., Suite 608

Los Angeles, CA 90064

[1] “About Us,” Human Rights Watch, accessed June 24, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/about-us.

[2] Human Rights Watch, The Price of Freedom: Bail and Pretrial Detention of low Income Nonfelony Defendants in New York City, December, 2010. https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/12/02/price-freedom/bail-and-pretrial-detention-low-income-nonfelony-defendants-new-york

[3] Human Rights Watch, “Not in it for justice”: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017. https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/11/not-it-justice/how-californias-pretrial-detention-and-bail-system-unfairly

[4] Human Rights Watch, Not in it for Justice: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017, pp. 42-43.https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/11/not-it-justice/how-californias-pretrial-detention-and-bail-system-unfairly

[5] Human Rights Watch, Not in it for Justice: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017, pp. 65-77. https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/11/not-it-justice/how-californias-pretrial-detention-and-bail-system-unfairly

[6] Human Rights Watch, Not in it for Justice: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017, pp. 51-64. Stories describing this situation are found throughout the report. https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/11/not-it-justice/how-californias-pretrial-detention-and-bail-system-unfairly

[7] Human Rights Watch, Not in it for Justice: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017, p. 56. https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/11/not-it-justice/how-californias-pretrial-detention-and-bail-system-unfairly

[8] Illinois State Bar Association, The Bar News, “Illinois Supreme Court Adopts Statewide Policy Statement for Pretrial Services.” https://www.isba.org/barnews/2017/05/01/illinois-supreme-court-adopts-statewide-policy-statement-pretrial-services (accessed June 24, 2019)

[9] Human Rights Watch, “Human Rights Watch advises against using profile-based risk assessment in bail reform,” July, 2017. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/17/human-rights-watch-advises-against-using-profile-based-risk-assessment-bail-reform

[10] Laura and John Arnold Foundation, “Public Safety Assessment: Risk factors and formula.” https://www.psapretrial.org/about/factors (accessed June 24, 2019)

[11] Elizabeth Hinton et al., “An Unjust Burden: The Disparate Treatment of Black Americans in the Criminal Justice System,” Vera Institute of Justice, May 2018. https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/for-the-record-unjust-burden/legacy_downloads/for-the-record-unjust-burden-racial-disparities.pdf (accessed June 24, 2019)

[12] Human Rights Watch, Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States, October, 2016. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/12/every-25-seconds/human-toll-criminalizing-drug-use-united-states

[13] Elizabeth Hinton et al., “An Unjust Burden: The Disparate Treatment of Black Americans in the Criminal Justice System,” Vera Institute of Justice, May 2018. https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/for-the-record-unjust-burden/legacy_downloads/for-the-record-unjust-burden-racial-disparities.pdf (accessed June 24, 2019)

[14] Laurel Eckhouse, “Big data may be reinforcing racial bias in the criminal justice system,” Washington Post, February 10, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/big-data-may-be-reinforcing-racial-bias-in-the-criminal-justice-system/2017/02/10/d63de518-ee3a-11e6-9973-c5efb7ccfb0d_story.html?utm_term=.0bd98097310d (accessed June 24, 2019)

[17] Human Rights Watch, Not in it for Justice: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017, p. 91.

[18] Santa Cruz County Probation Department, Alternatives to Custody Report 2015, April 2016, p.11. file:///C:/Users/raphlij/Downloads/Snapshot-5956.pdf; Human Rights Watch, Not in it for Justice: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017, pp. 99-100. https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/11/not-it-justice/how-californias-pretrial-detention-and-bail-system-unfairly

[19] Megan Stevenson, Assessing Risk Assessment in Action, (December 8, 2017), George Mason Legal Studies Research Paper No. LS 17-25. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3016088 (accessed June 24, 2019)

[20] Human Rights Watch, Not in it for Justice: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People, April, 2017, pp. 59-62. https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/11/not-it-justice/how-californias-pretrial-detention-and-bail-system-unfairly

[21] Julia Angwin et al., “Machine Bias,” ProPublica, May 23, 2016, https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing; Rowan Walrath, “Software Used to Make ‘Life-Altering’ Decisions Is No Better Than Random People at Predicting Recidivism,” Mother Jones, January 17, 2018. https://www.motherjones.com/crime-justice/2018/01/compas-software-racial-bias-inaccurate-predicting-recidivism/ (accessed June 24, 2019)

[22] The Arnold tool has some degree of transparency about the factors it considers and how they are weighted. See Laura and John Arnold Foundation, “Public Safety Assessment: Risk factors and formula.” https://www.psapretrial.org/about/factors However, Arnold has been criticized for not revealing how it developed its algorithms, why it used the data it chose to develop the system, whether it performed validation, and, if it did, what the outcomes were. John Logan Koepke and David G. Robinson, “Danger Ahead: Risk Assessment and the Future of Bail Reform,” Washington Law Review, Vol. 93, December, 2018, p. 1803. http://digital.law.washington.edu/dspace-law/bitstream/handle/1773.1/1849/93WLR1725.pdf (accessed June 24, 2019)

[23] Article 9(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf (accessed June 24, 2019) The US has ratified the ICCPR.

[24] Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Report on the Use of Pretrial Detention in the Americas, OEA/Ser.L/V/VII, Doc. 46/13 (2013), para. 186. https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/pdl/reports/pdfs/Report-PD-2013-en.pdf (accessed June 24, 2019); The United States has signed, but not ratified, the American Convention, and as such is not legally bound by its provisions. However, the Inter-American Commission’s guidance is a useful and authoritative guide to the protection of fundamental human rights. This is particularly true in this area, because the American Convention’s due process guarantees are in many respects similar to those guaranteed under US law and by international instruments binding on the United States.

[25]https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2019/Bail_Reform_NY_Summary.pdf The New York law does not get rid of money bail in all cases, but restricts its use. It does not prohibit risk assessment, but does not require or encourage its use. It does set standards on the tools to mitigate their harms.

[26] Los Angeles Community Action Network, “Preserving the Presumption of Innocence: A New Model for Bail Reform,” http://cangress.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Preserving-the-Presumption-of-Innocence-Final-1.pdf (accessed June 24, 2019)

[27]Aurelie Ouss and Megan Stevenson, “Evaluating the Impacts of Eliminating Prosecutorial Requests for Cash Bail,” February 17, 2019. file:///C:/Users/raphlij/Downloads/SSRN-id3335138.pdf (accessed June 24, 2019)

Your tax deductible gift can help stop human rights violations and save lives around the world.

Region / Country

Most Viewed

-

March 9, 2026

Lebanon: Israel Unlawfully Using White Phosphorus

-

-

March 7, 2026

US/Israel: Investigate Iran School Attack as a War Crime

-

November 25, 2019

A Dirty Investment

-

July 21, 2025

“You Feel Like Your Life Is Over”