August 15, 2018

Dr. Faith Kumalo

Chief Director, Care and Support in Schools

Private Bag X895, Pretoria 0001

South Africa

pregnancypolicy@dbe.gov.za

Dear Dr. Kumalo,

Please accept our regards on behalf of Human Rights Watch.

We are writing further to the feedback we provided via email on July 31, 2018.

We welcome the Department of Basic Education’s (DBE) consultation on its draft national policy on the prevention and management of learner pregnancy in schools with stakeholders and education actors interested in ensuring pregnant students and adolescent parents fully benefit from their right to education.

We would like to share our most recent report, Leave No Girl Behind in Africa, which focuses on pregnancy discrimination in education across the African Union and outlines recommendations for rights-compliant pregnancy management policies. Please find a copy enclosed with this letter.

We strongly encourage the DBE to adopt a robust policy that aims to fully protect the right to education of adolescent mothers and fathers and prevent teenage pregnancies, in compliance with its human rights obligations.

Based on our research findings, we would like to take this opportunity to provide comments and recommendations on the draft policy.

We have found that successful policies best serve the interests of pregnant learners and adolescent mothers, and often focus on providing continuation in education access, rather than restricting a learner’s return to school. On this basis, rather than providing a conditional period of time for re-entry into school, learners who become mothers return to school once they decide they are able to resume classes. Imposing a conditional period of time, or numerous, and potentially costly, conditions to secure their return often discourages girls from returning to school.

We therefore strongly encourage the DBE to focus on a “continuation” policy, rather than adopting a policy that provides for a conditional “re-entry”.

Although adolescent girls are disproportionately affected by teenage pregnancy, and require specific accommodations on that basis, a robust policy should also focus on male learners who become adolescent fathers. The DBE should ensure that the policy includes guidance focused on them —including provisions for time off, accommodations, and counselling—on an equal basis with adolescent mothers.

Our research found that countries that do have policies in place, often lack an adequate implementation and monitoring plan. We note that the implementation plan – perhaps the most crucial part of this policy – was not made public, and encourage the DBE to open it for consultation. We also encourage the DBE to ensure this plan includes very specific guidance to ensure the principles of the policy are fully respected by school officials, teachers and education staff.

A successful plan should be accompanied by a monitoring plan to ensure students’ return to school, and the conditions they face once they return. We would also encourage the DBE to monitor retention periods of adolescent mothers and fathers, to understand whether the policy is effective.

Research and case-law led by South African organisations shows evidence that some school officials continue to turn learners down, contradicting their obligations to respect learner’s right to compulsory education.[1] We would therefore strongly recommend that the DBE communicates a clear obligation on all education establishments to respect girls’ right to stay in school during pregnancy, and to return during motherhood. School management committees should not have discretion over how the DBE’s policy should be interpreted. Schools should not be able to implement or adhere to policies or regulations that may block a student’s return to school. The implementation plan should emphasize that all provincial departments of education will be held accountable for the implementation of the policy.

We welcome the dual focus on prevention and management of pregnancies – and the DBE’s commitment to provide access to an age-appropriate, scientifically accurate sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) -embedded in its comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) curriculum. The draft policy should stipulate the mandatory nature of this curriculum, and should specify that learners will have access to comprehensive sexuality education from primary school, in line with international guidance.

We note the DBE’s commitment to expand its CSE curriculum to ensure learners learn about responsible sexual relationships, and how to stay protected, alongside abstention. Global scientific, sociological and human rights evidence shows that an abstinence-only curriculum leads to no visible change in adolescent sexual behavior.[2] A heavy focus on abstinence also isolates and humiliates many adolescents who have already had sexual relationships, and prevents them from obtaining the information and services that will protect them from abuse, unwanted pregnancy, or HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.[3]

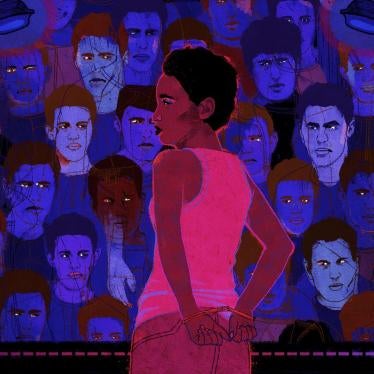

As part of an inclusive school environment, schools should also focus on reducing stigma and discrimination against teenage parents within schools. They should dedicate attention and resources to protecting and supporting pregnant students and adolescent parents, and ensuring schools engage other students in discussions on teenage pregnancy. The policy should add a component of official and extra-curricular discussions within schools on this topic, complementing topics covered in its revamped sexual and reproductive health education curriculum.

Moreover, in order to guarantee full inclusion, and in line with the DBE’s overall commitments on inclusive education, the DBE should guarantee that all materials and information produced or provided in the context of its Integrated School Health Policy (ISHP), are fully accessible and available to all students with disabilities.

In addition to focusing on “managing” pregnancies and mitigating the impact on the education system, the DBE’s policy should respond to a learner’s needs as a young mother.

We recommend that basic accommodations be made explicit in the policy, including: time for pre-natal checks (where those cannot happen outside class time), time to breastfeed during breaks, time off in case her child is ill or to comply with other medical or bureaucratic requirements. We would also encourage the DBE to clarify that medical certificates are provided free of charge, and to ensure that young mothers do not absorb the additional costs associated with the conditions presented in this draft policy.

We also believe it is important for the DBE to include accommodations for exam time to ensure pregnant students do not lose an academic year because they were not allowed to take an exam, or were not allowed to continue classes based on medical advice.

We would similarly recommend that the policy defines what a “disproportionate” amount of time is to ensure schools are guided by certain parameters when they assess how much time away from school could affect a learner’s education.

We thank you for taking these recommendations into account, and look forward to engaging with your team in the development of the policy and its implementation plan.

Sincerely,

Elin Martínez

Researcher, Children's Rights

Agnes Odhiambo

Senior Researcher, Women's Rights

[1] Lisa Draga, Chandré Stuurman, and Demichelle Petherbridge, “Basic Education Rights Handbook – Education Rights in South Africa – Chapter 8: Pregnancy,” 2017, available at http://section27.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Chapter-8.pdf.

[2] Janet Burns, “Research Confirms that Abstinence-Only Education Hurts Kids,” Forbes, August 23, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/janetwburns/2017/08/23/research-confirms-the-obvious-that-abstinence-only-education-hurts-kids/#5abb07c66152 (accessed February 17, 2018); John Santelli and Mary A. Ott, “Abstinence-only education policies and programs: A position paper for the Society for Adolescent Medicine,” 38 Journal of Adolescent Health, 2006, https://www.adolescenthealth.org/SAHM_Main/media/Advocacy/Positions/Jan-06-Abstinence_only_edu_policies_and_programs.pdf (accessed February 18, 2018), pp. 83- 87; Human Rights Watch, ““The Less They Know, the Better,” Abstinence-Only HIV/AIDS Programs in Uganda,” March 2005 https://www.hrw.org/report/2005/03/30/less-they-know-better/abstinence-only-hiv/aids-programs-uganda.

[3] Human Rights Watch interview with Dame Ndiaye, coordinator, Right Here, Right Now, Dakar, Senegal, August 12, 2017.