(New York) – Newly released documents reveal a US Defense Department policy that appears to authorize warrantless monitoring of US citizens and green-card holders whom the executive branch regards as “homegrown violent extremists,” Human Rights Watch said today. Separately, the documents also reinforce concerns that the government may be gathering very large amounts of data about US citizens and others without warrants. Both issues relate to a longstanding executive order that is shrouded in secrecy and should be a focus of congressional inquiry.

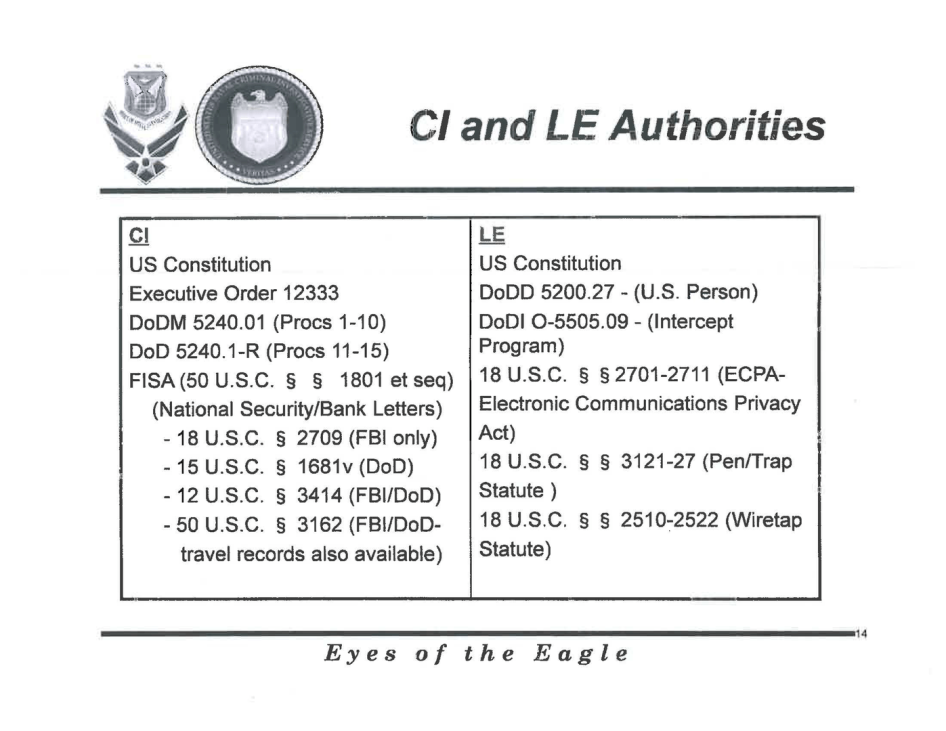

The new materials, which Human Rights Watch obtained through a freedom of information request, are training modules that primarily concern Executive Order 12333 (EO 12333). That order broadly governs the US intelligence agencies’ activities, and includes provisions allowing the agencies to collect information on US persons – meaning US citizens and lawful permanent residents, as well as some corporations and associations – in a manner the government has never fully explained to the public. The training slides largely summarize Defense Department procedures concerning EO 12333 that were released in 2016, updating a 1982 version. Using plain language to demystify the procedures’ phrasing, the slides offer hints about Defense Department intelligence practices that require further inquiry and exposure.

“These documents point to just how thoroughly the public has been kept in the dark about warrantless surveillance under Executive Order 12333,” said Sarah St.Vincent, US surveillance and national security researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Their explanations of the order suggest that the government may be carrying out monitoring that poses serious problems for human rights, and Congress should seek more information about what the intelligence agencies are doing in this respect.”

One of the documents’ most troubling aspects is the indication that the Defense Department has authorized its intelligence components to carry out at least some forms of monitoring of US persons without a warrant, based on designations that use unknown and potentially discriminatory criteria. Specifically, one of the training documents indicates that this monitoring is permitted for US persons whom the government regards as “homegrown violent extremists” (referred to as “HVEs” in the slides) – even when they have “no specific connection to foreign terrorist(s).” The government’s basis for this authorization is a revised definition of “counterintelligence” collection found in the 2016 procedures.

The procedures address several forms of surveillance, and it is unclear which types the government plans to use when monitoring “homegrown violent extremists.” However, a current senior Defense Department official who provided comments to Human Rights Watch on condition of anonymity stated that “the [Department’s] counterintelligence elements would be unable to collect necessary information on potential HVEs” without this change.

The Defense Department official did not respond to a question from Human Rights Watch about whether the monitoring of US persons under this policy may include electronic surveillance. If it does, this would raise concerns that the government is violating – or believes it is exploiting a possible loophole in – federal law, which generally prohibits deliberate spying on the content of US persons’ telephone or internet communications without a warrant.

The authorities may only obtain such a warrant if they show probable cause to believe that the person has committed or is about to commit a crime, or that the person is “a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power.” The disclosure of the government’s policy regarding the surveillance of “homegrown violent extremists” who are not connected to a foreign group raises concerns about whether intelligence and/or law enforcement bodies are using EO 12333 to do an end-run around these legal protections.

Human Rights Watch is also concerned about the methods and criteria the government may be using to define and identify “homegrown violent extremists,” and particularly about the risk that people who are exercising their legitimate free-expression rights will be targeted for monitoring in a discriminatory or arbitrary manner. As an example of “homegrown violent extremists,” the Defense Department official who commented to Human Rights Watch pointed to individuals who “may be self-radicalized via the internet, social media, etc., and then plan or execute terrorist acts in furtherance of the ideology or goals of a foreign terrorist group.” However, the official did not respond to a question about the criteria the executive branch uses when designating a US person a “homegrown violent extremist” for the purposes of this policy.

Additional questions remain about the range of agencies that may warrantlessly monitor such individuals. The Defense Department official’s comments imply that the policy disclosed in the slides applies to the Department’s “counterintelligence elements,” such as the Naval Criminal Investigative Service and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations. These bodies, the official stated, “investigate activities by active duty military members of their Service or [Defense Department] civilian personnel engaged in activities targeted against interests of their Service.” The official noted, “If the military counterintelligence elements conduct investigations of persons other than active duty military members, they do so jointly with the FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation].”

Although the official’s remarks focused on the military counterintelligence bodies, further information is needed about whether other agencies – such as the National Security Agency (“NSA”) or the FBI – may rely on similar policies to identify and/or monitor US persons who do not have an affiliation with the military, Human Rights Watch said.

The Defense Department official emphasized that “counterintelligence collection against these, or any other individuals or groups, must be predicated upon the ‘reasonable belief’ standard, which is reviewed through the operational and legal chain of command prior to initiation of any activity. Field personnel may not rely solely upon ‘hunches’ or intuition’ as justification for the initiation of counterintelligence activities.” However, the government’s failure to disclose its methods and criteria for designating US-person “extremists” makes the effectiveness of these stated protections difficult to evaluate.

“The government’s authority to monitor people doesn’t depend on their beliefs, or what the government thinks they believe, but on specific evidence that gives sufficient reason to think a criminal offense is occurring or that the person is an agent of a foreign power,” St.Vincent said. “A secret determination that someone’s rights should be curtailed based on undisclosed criteria is incompatible with the rule of law. The government should explain what it’s doing as well as its legal basis for doing it.”

A separate problem to which some of the newly released materials point is the potential volume of data collection – including collection affecting US persons – under EO 12333. The 2016 procedures created the category of “special circumstances collection” to encourage the authorities to consider whether surveillance activities “raise special circumstances” and merit extra safeguards based on “the volume, proportion, and sensitivity” of US-person information the government is likely to obtain. (The category itself does not authorize any surveillance that could not otherwise take place under the order.) However, the training documents use the informal term “big data” to describe “special circumstances collection,” raising the possibility that the government may be carrying out or contemplating surveillance on a massive scale.

Documents revealed by the former NSA contractor Edward Snowden beginning in 2013 have indicated that the government uses EO 12333 as the basis for bulk communications surveillance programs overseas. However, these new references to “big data,” while fleeting, appear to represent one of the most direct acknowledgments yet by the government that warrantless monitoring under the order may entail seizing very large or systematic sets of data – including about US persons.

Details regarding the newly released documents are provided below, and the documents themselves are posted on the Human Rights Watch website. Human Rights Watch shared the documents with Reuters, which published a related story on October 25.

Human Rights Watch is also releasing documents obtained from the National Reconnaissance Organization and the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis.

To view the documents, please visit:

Air Force Office of Special Investigations FOIA documents

National Reconnaissance Office FOIA documents

DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis FOIA documents

The following are elements of the training documents obtained by Human Rights Watch that give rise to new concerns.

- Expansion of warrantless Defense Department intelligence collection on US persons for “counterintelligence” purposes to include “homegrown violent extremists”

One of the documents indicates that pursuant to a 2016 change in procedures concerning Executive Order 12333, the Defense Department may now extend the monitoring of US persons for “counterintelligence” purposes to people the government regards as “HVEs,” which a senior Defense Department official consulted by Human Rights Watch confirmed means “homegrown violent extremists.” The official indicated that the term is “shorthand … used in the counterintelligence community to describe people who may not have a specific connection to a particular foreign terrorist group but are engaged in violent extremist activities, often following engagement with these groups’ propaganda on the Internet or social media, etc.”

The procedures themselves do not directly mention such “homegrown violent extremists,” instead providing in more general terms that the monitoring of US persons for “counterintelligence” purposes may extend to “[a]n individual, organization, or group reasonably believed to be acting for, or in furtherance of, the goals or objectives of an international terrorist or international terrorist organization, for purposes harmful to the national security of the United States.”

In indicating that this category includes “HVEs,” the training document depicts this expansion of the “counterintelligence” collection definition as a “[k]ey” change in the new procedures. The document indicates that the change allows the collection of intelligence on US persons even in the absence of a “specific connection to foreign terrorist(s).” As examples, it alludes to the individuals who carried out mass shootings in San Bernardino, California in 2015, and in Orlando, Florida in 2016.

The Defense Department’s methods and criteria for identifying “homegrown violent extremists” remain unclear, raising fears that the designation could be applied in ways that are arbitrary, inconsistent, or discriminatory. It is also unknown whether US persons who merely exercise their free-expression rights by visiting a controversial website, espousing certain political or religious views, or criticizing the government might be targeted.

The government also has not yet disclosed its legal justification for this policy, especially insofar as it involves any warrantless monitoring of US persons that would normally require a warrant under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, other statutes, or Fourth Amendment case law. The government should fully disclose the policy, its legal underpinnings, the type(s) of monitoring to which it may lead, and its anticipated and actual application.

Human Rights Watch remains concerned that several other aspects of this important policy change have not yet been publicly revealed. For example, as mentioned above, it is not yet clear whether the policy (or a similar one) may also apply to the NSA or non-Defense intelligence agencies, or whether people who have no affiliation with the Defense Department may be monitored.

- “Special circumstances” collection and references to “big data”

The Defense Department procedures adopted in 2016 refer to the idea of “Special Circumstances Collection”: intelligence “collection opportunities” for which certain extra safeguards may be appropriate due to the “volume, proportion, and sensitivity of the [US person information] likely to be acquired,” as well as the “intrusiveness of the methods used to collect the information.” The Defense Department official Human Rights Watch consulted said the concept of special circumstances collection itself “does not provide any new or independent authority to conduct electronic surveillance”; that is, it does not give the Defense Department any powers it did not already have. However, the scope and scale of such collection is unknown, including the kinds of data that may be collected.

Two of the newly disclosed training documents suggest that at least some of the collection the government may be carrying out that falls into the “special circumstances” category includes the gathering of “big data” – a term that lacks a settled definition but can refer to enormous troves of information. These explicit references to “big data” raise renewed concerns that under EO 12333, the government may be sweeping up huge amounts of data containing private communications or other sensitive information – including information belonging to US persons. They may also be some of the most direct acknowledgments yet by the government itself of this possibility.

The possibility of the collection of “big data” is particularly troubling in light of the Defense Department’s power to disseminate “large amounts of unevaluated” information about US persons to entities both within and outside the federal government, as confirmed in the 2016 procedures.

Congress should seek, and the executive branch should provide, detailed explanations of the scale and nature of all “special circumstances collection” activities, including their impact on US persons.

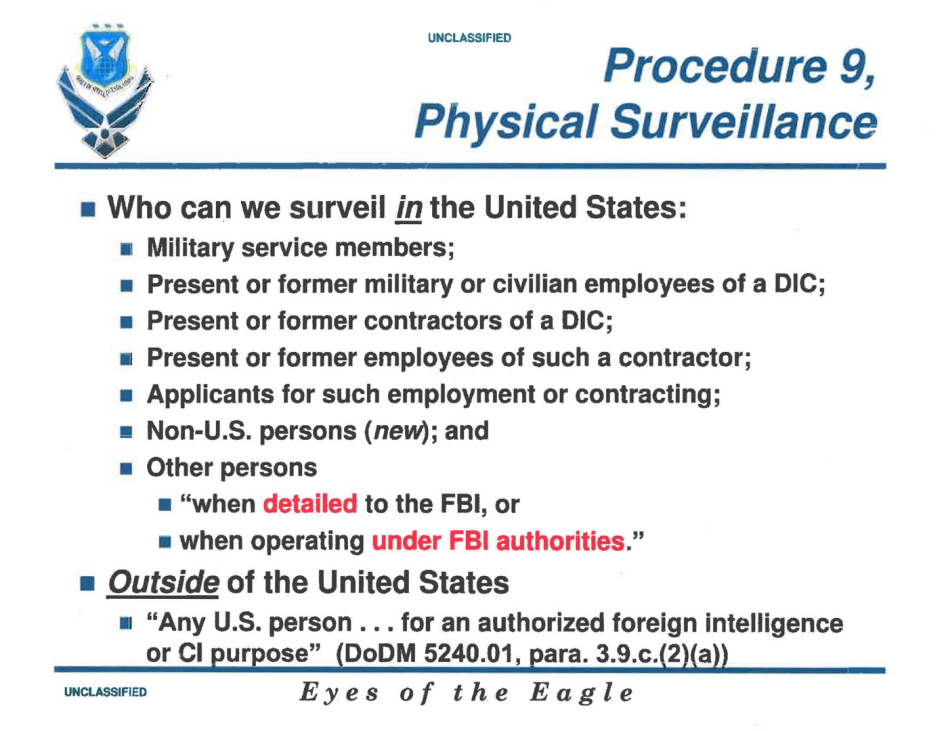

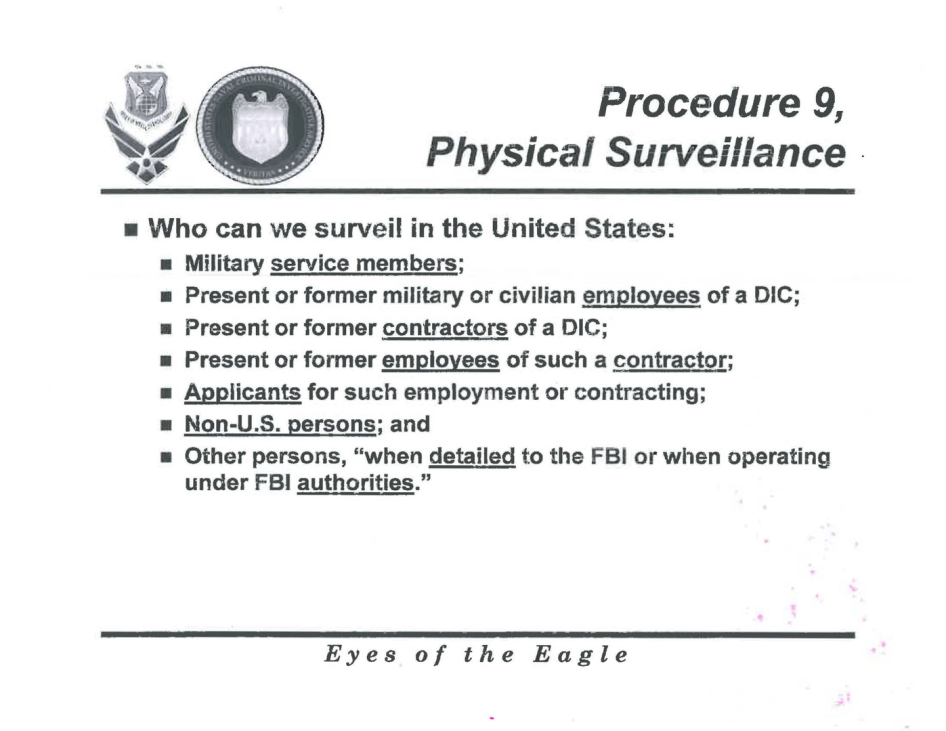

- “Physical surveillance” of non-US persons in the United States

The 2016 Defense Department procedures define “physical surveillance” as the “deliberate and continuous observation … of a person to track his or her movement or other physical activities while they are occurring, under circumstances in which the person has no reasonable expectation of privacy,” and say this monitoring may include the use of “enhancement devices” such as “binoculars or still or full motion cameras.”

The new training documents highlight a section of these procedures that allows the Defense Department’s intelligence components to conduct such physical surveillance of any non-US person in the US without a warrant, as long as the surveillance takes place for “an authorized foreign intelligence or [counterintelligence] purpose.” Non-US persons in the US include undocumented immigrants and temporary visa holders.

By comparison, the Defense Department’s intelligence components may only subject US persons in the US to such physical surveillance if they are current or prospective employees of (or contractors for) those components, or if they are members of another element of the armed services.

The senior Defense Department official Human Rights Watch consulted indicated that this new provision of the procedures “was needed to maintain [a] long standing rule that allows the physical surveillance of non-U.S. persons inside the U.S.” This rule was not stated explicitly in the earlier version of the procedures, although the government appears to view it as having been implicit.

The rule raises troubling questions about whether the government, contrary to the general understanding that all persons in the territory of the US enjoy rights under the constitution, believes it has wider latitude to engage in national security or criminal surveillance of non-US persons in the US than it does to surveil US citizens and green-card holders in the country. The policy also prompts questions about its potential effect on any US persons who become caught in a dragnet intended for non-US persons.

“Physical surveillance” does not include communications surveillance. However, some activities that may qualify as “physical surveillance” may have Fourth Amendment implications: for example, US federal courts are currently divided as to whether the government needs a warrant for continuous video monitoring of areas that are visible to the public. The government should clarify what the manual means when it refers to “circumstances in which the person has no reasonable expectation of privacy”; it should also explain the specific types of monitoring that may take place under this policy as well as any rules for storing, searching, and sharing the data.

As a general matter, the government should explain how it regards the Fourth Amendment as applying to people in the US who are not citizens or lawful permanent residents.

- Military law enforcement “Intercept Program” associated with Department of Defense Instruction O-5505.9

One training document briefly refers to an “Intercept Program” associated with Department of Defense Instruction O-5505.9 – a document whose current version is not publicly available, although a 1995 version addressed the interception of wire, electronic, and oral communications for law enforcement by Defense Department entities. The Defense Department official said the program “pertains exclusively to DoD law enforcement entities” and that Instruction O-5505.9 “does not authorize any DoD intelligence activity.” The government should release this instruction along with information about its uses.

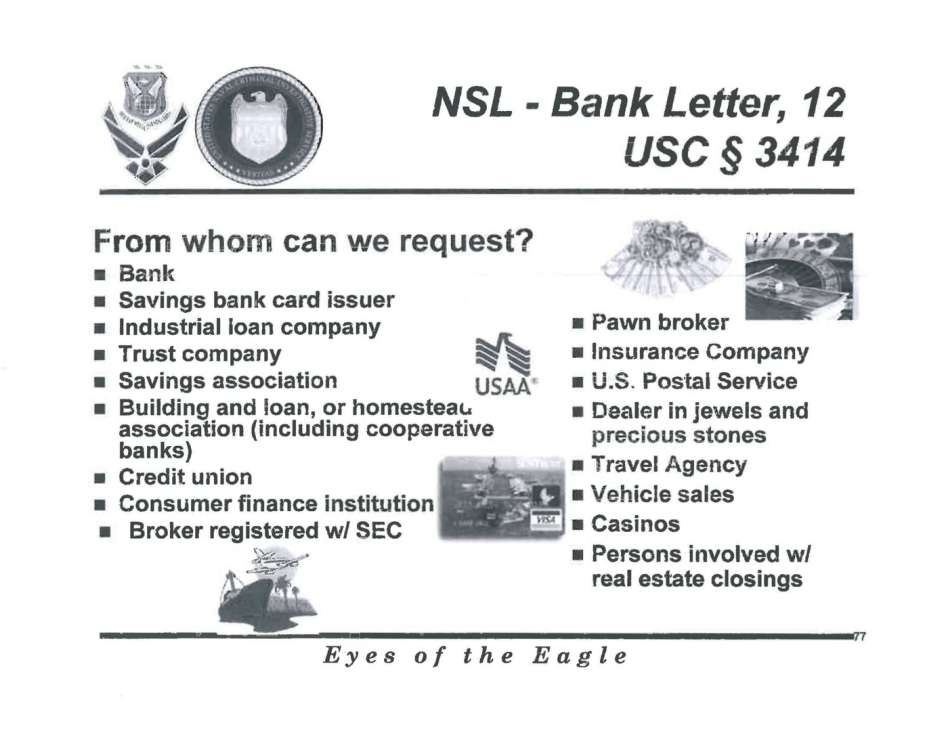

- National Security Letters

A set of slides in one of the training presentations offers a stark illustration of the possible scope of warrantless National Security Letters, which the government may use to obtain financial and other records as part of foreign intelligence and international terrorism investigations. While the information found in the slides was already publicly available, the array of records the FBI may seek through the letters without court approval – from bank account and credit card transaction histories to documents held by pawnbrokers, jewelers, travel agencies, car dealers, real estate agents, and casinos – is vividly on display.

- Recommendations to the US government

The US executive branch should release clear and comprehensive information about the monitoring the intelligence agencies may conduct under Executive Order 12333 and other surveillance authorities.

In response to specific concerns raised by the new materials, the executive branch should:

- Ensure that all surveillance authorities, legal interpretations, and policies are clear, detailed, and publicly available. The language in these documents should enable the public to understand the circumstances in which surveillance may take place.

- Release any legal interpretations or policies concerning the definition, designation and monitoring of US persons the government regards as “homegrown violent extremists.”

- Provide explanations and legal justifications for all “special circumstances collection” activities, as well as an explanation of their scale.

- Provide a clear and comprehensive explanation of the types of “physical surveillance” to which non-US persons in the US may be subjected as well as the sharing, storage, and usage of any resulting data.

- Disclose Department of Defense Instruction O-5505.9 and explain the activities conducted under that authority.

The US Congress should also ask for further information about each of the policies and activities detailed above, and ensure that all government surveillance complies with US constitutional and international human rights law and takes place within a statutory framework that is effective in preventing abuses. Congress should also ensure that as much information as possible is disclosed to the public.