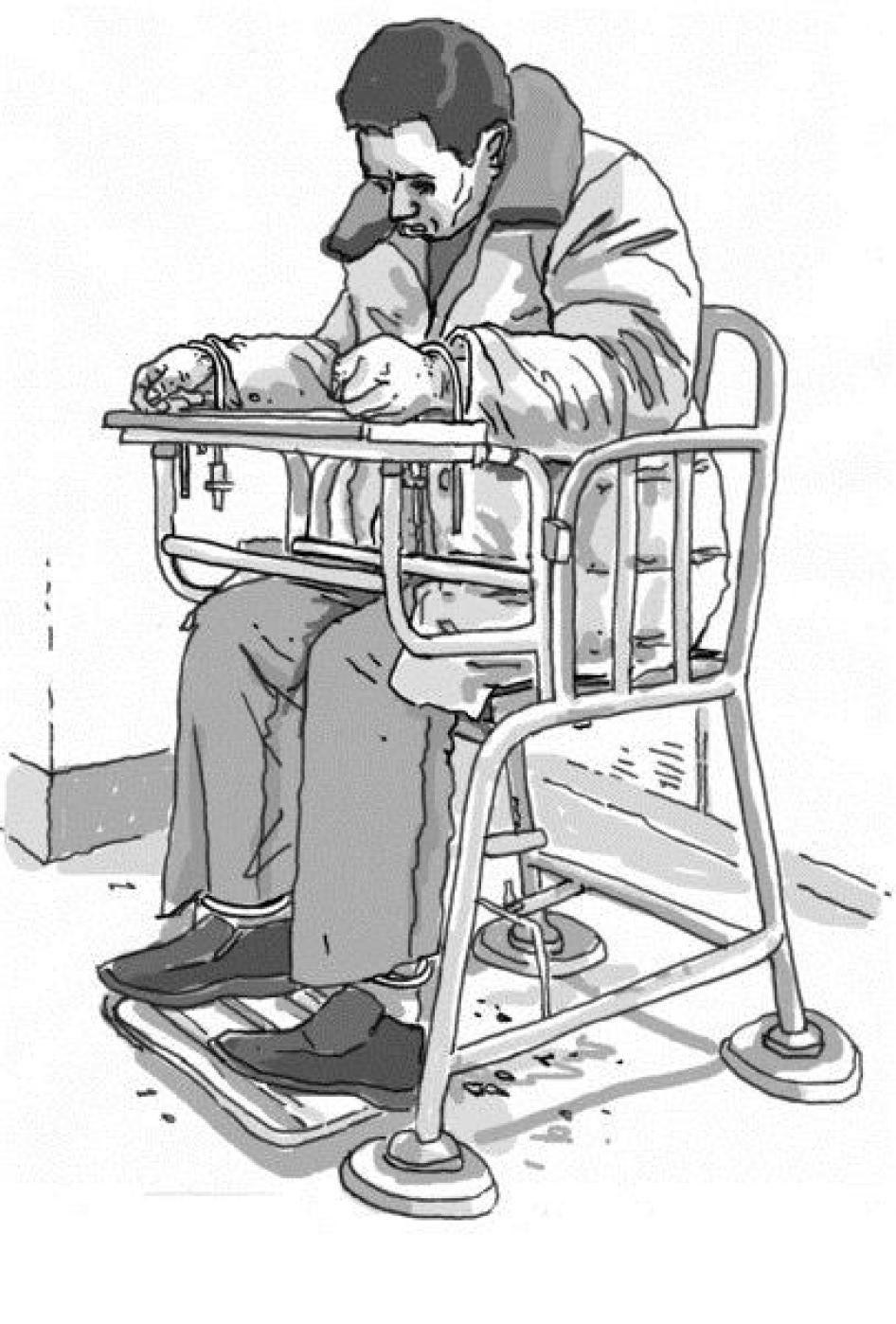

“Chunfu was thin like sticks, he was pale, his eyes lifeless.” This was the initial reaction of Bi Liping when she went to the local police station on January 12, 2017, and saw her husband, human rights lawyer Li Chunfu. After more than 500 days of secret detention, Li had been “released on bail.”

It was soon apparent that the once tough, lively human rights defender had changed dramatically, and not just in terms of his appearance: Li is now fearful and paranoid. When he first arrived home, he was too afraid to enter; once he did he was too afraid to leave. Soon after his abrupt release, a Beijing psychiatric hospital gave him a tentative diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Li is one of the more than 300 human rights lawyers and advocates whom the Chinese authorities rounded up nationwide in July 2015. Though most have been released, four remain detained while two were imprisoned. Others “released on bail” have been forced into silence. Li’s situation raises alarms over the treatment of those still held.

Li grew up poor in Henan Province, dropping out of school to work in factories. He eventually taught himself law and started practicing in 2005. He chose to become a human rights lawyer, one who “cherished each case he took,” according to his sister-in-law. Li’s life experiences fighting injustice made him a strong figure.

It’s no mystery what shattered him. Human Rights Watch has long documented the Chinese government’s use of torture, and human rights defenders are frequently treated harshly. Beatings, being hung up by the wrists, prolonged sleep deprivation, indefinite isolation, threats to one’s family – these are common techniques that can cause long-term physical and psychological harm.

It is less clear why Li Chunfu was targeted. Perhaps it was his 2014 demonstration outside a Heilongjiang police bureau, demanding access to his client. Perhaps it is guilt by association, since he is the brother of another prominent rights lawyer, Li Heping. Increasingly Beijing tries to tar activists as agents of hostile governments, and perhaps the authorities had painted Li Chunfu and fellow lawyers as such to justify more draconian treatment.

The Chinese government owes Li and his family answers – why Li was detained, what happened to him in custody, and who was responsible for his mistreatment. More than that, it has a legal obligation to pay for his medical care and rehabilitation and prosecute those responsible. Beijing will have zero credibility on the rule of law both at home and abroad so long as individuals are tortured with impunity. Li will likely never be the same after this horrific experience – and neither should Beijing.