Summary

Almost from the beginning of my imprisonment, I had pains, swelling and stiffness in my body. My complaints were either ignored and jail staff would ask me to “man up” and “suck it up,” or on certain occasions I was given a painkiller. I could hardly stand up in the morning and kept pleading for an MRI or an ultrasound, but my requests were ignored. It was only when I was finally released that I was diagnosed with arthritis.

— Aslam, 54, inmate in a Lahore prison from 2017-2020

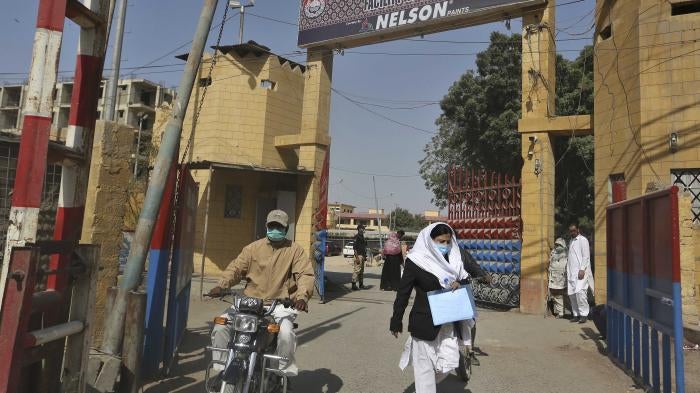

Pakistan has one of the world’s most overcrowded prison systems. As of 2022, many of its 91 jails and prisons were more than 100 percent over capacity. Severe overcrowding has compounded existing health deficiencies in prisons, leaving inmates vulnerable to communicable diseases and unable to access medicine and treatment for even basic health needs. The 2020 outbreak of Covid-19 exposed some of the worst of these abuses, which long pre-dated the pandemic and have persisted without remedy since. The floods that devastated Pakistan in mid-2022 caused further damage to many facilities, especially in Sindh province, and left prison populations even more isolated and vulnerable to water-borne disease.

Poor health care intersects with range of other rights violations against prisoners, including torture and mistreatment, and is a key symptom of a broken criminal justice system. Corruption among prison officials and guards and impunity for abusive conduct contribute to serious human rights abuses in prisons and jails, including inadequate and poor-quality food, unsanitary living conditions, and lack of access to medicines and treatment. The crisis in prison health care also reflects deeper failures in access to health care across Pakistan, exacerbated most recently by an economic crisis that plunged Pakistan’s economy into turmoil in 2022. For decades, Pakistan has budgeted less than 3 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on health, significantly below World Health Organization (WHO) standards.

This report documents widespread deficiencies in prison health care in Pakistan, and the consequences for a total prison population of more than 88,000 people. It is based on 34 in-person and telephone interviews with former inmates in Sindh and Punjab provinces, and the Islamabad capital territory, including women and juveniles, as well as some two dozen interviews with lawyers for pre-trial detainees and convicted prisoners, prison health officials, and representatives of organizations working on prisoner rights. Although we did not conduct an exhaustive survey of all of Pakistan’s prisons and jails, interviews with lawyers working with diverse prison populations across the country, including in rural areas, corroborated our findings, as did recent reports by official bodies and nongovernmental prisoner rights groups. While torture by police and prison authorities is widespread and seldom prosecuted, this report does not focus on torture but on the barriers prisoners and detainees face in accessing health care.

Prison conditions in Pakistan have been poor since the colonial period, from which time much current prison law dates. However, conditions have worsened as the prison population has swelled. Pakistan’s prison population is drawn largely from the poorest sectors of society, those unable to pay bribes, raise bail, or hire lawyers to help them navigate alternatives to incarceration. Harmful government and societal attitudes that see prisoners as “deserving of punishment” contribute to apathy and mistreatment.

Successive governments and political parties in Pakistan have ignored the need for prison reform; even horrific examples of mistreatment have rarely caught the attention of parliament or resulted in change.

Poor infrastructure and corruption have left prison healthcare services vastly overstretched. Most prison hospitals lack adequate budgets for medical staff, essential equipment like EKG machines, and sufficient ambulances. In one stark example of neglect, in December 2021 six prisoners in Lahore’s Camp Jail died within 12 days of being taken into custody after their health deteriorated. The facility had no healthcare personnel at the facility at the time, and despite freezing temperatures the cells lacked heating and the prison provided no warm clothing for inmates. Yet, their deaths did not result in reforms or accountability.

Widespread corruption has plagued Pakistan’s government institutions for decades, with the criminal justice and prisons system generally viewed as among the most corrupt. A culture of bribery has created two separate systems for those with wealth and influence and all others. While most Pakistani prisoners are denied the basic health care to which they are entitled under law, a small group of rich and influential inmates serve out their sentences outside prison in private hospitals. Poorer prisoners have to pay bribes just to obtain painkillers.

Overcrowding

Pakistani prisons are notoriously overcrowded, with cells designed for a maximum of three people holding up to 15. The principal cause for overcrowding is the dysfunctional criminal justice system itself. The majority of inmates in Pakistan’s prisons are under-trial – awaiting trial or in the midst of trial – and yet to be convicted. Delays plague the system, with trials routinely taking years to complete while the accused stay in prison. Expansive colonial-era laws grant police virtually unchecked powers to arrest people often without meeting international standards that suspects be informed promptly and in detail of the nature and cause of the criminal charges against them. And despite international legal requirements that courts as a general rule provide bail to suspects, Pakistani courts frequently deny bail to detainees or set bail amounts beyond their financial reach when there is no threat of the detainee absconding or interfering in the case.

Most of those facing criminal trials are poor and, in the absence of a robust mechanism for state-provided legal aid, lack adequate legal representation. A lack of sentencing guidelines and the courts’ aversion to alternative non-custodial sentences even for minor offenses also significantly contribute to overcrowding.

Access to Food, Water and Sanitation

Almost all former prisoners interviewed for this report complained about unhealthy and inadequate food, dirty water, and unhygienic conditions. Tap water in Pakistan generally is unfit for drinking due to its high arsenic content. However, one medical officer told Human Rights Watch that when he demanded clean water for the prisoners, he said he was told: “These are criminals who are being punished. Stop treating them as if they were on vacation.” Prison authorities also compel prisoners to pay for food to which they are entitled. While wealthy prisoners have access to healthy food and fresh fruit, the majority are not provided even the substandard food designated for them.

Overcrowding, neglect, and crumbling infrastructure have left jails and prisons largely unfit for habitation. Prisoners themselves are assigned to clean cells, but cramped conditions make such cleaning futile. Scabies and other skin diseases are common, and cells are often infested with rats, lizards, and other vermin.

In a landmark decision in March 2020, the Islamabad High Court ruled that holding prisoners “in an overcrowded prison, having lack of sanitation, [is] tantamount to cruel and inhuman treatment for which the State ought to be accountable because it amounts to a breach of its fiduciary duty of care.” However, the court decision did not result in serious reform.

Discrimination Toward Women Prisoners

Women prisoners are among the most at-risk inmates. Patriarchal societal attitudes, lack of independent financial resources, and abandonment by families contribute to additional hardships for women prisoners. Women in the criminal justice system routinely experience prejudice, discrimination, and abuse, and face enormous difficulties accessing health care. One woman who spent three years in a prison in Lahore said:

Throughout my stay in prison, I suffered from acute migraines and hormonal issues causing pain and irregular menstruation cycles. I was not allowed to meet a specialist even once and was only given a painkiller. It is extremely difficult for us to speak about menstruation to a male prison official due to social taboos and embarrassment. Women prisoners are treated the worst because in Pakistan they are abandoned by their families, and no one comes to visit them and hence the prison authorities know that no one is willing to pay any [bribe] money for their better treatment.

Pakistan’s Ministry of Human Rights reported in 2020 that women prisoners received inadequate medical care and that officials routinely ignored laws meant to protect women prisoners. Nearly two-thirds of the women detained in Pakistani prisons are under-trial and have not been convicted of any crime.

A critical lack of funding in the prison healthcare system has meant that mothers whose children accompany them in prison often lack essential health care, leaving both women and children at risk. One prisoner said that her child, who has a developmental disability, was not offered any support services or medical care despite the prisoner’s repeated requests during her six years of incarceration.

Discrimination Faced by Prisoners with Disabilities

Prisoners with disabilities are at particular risk of abuse, discrimination, and mistreatment. A lack of awareness about mental health in Pakistani society contributes to the abuse of those with psychosocial disabilities (mental health conditions), and prisoners who ask for mental health support are often mocked and denied services. The prison system lacks mental health professionals, and prison authorities tend to view any report of a mental health condition with suspicion. Psychological assessments for new prisoners are either perfunctory or not done at all. A prisoner who had spent four months in a Lahore prison in 2018 said that he had depression and was thinking of ending his life. He said that when he requested professional help, an official told him, “Everyone here is depressed. Even I am depressed. You should start praying.”

Colonial-era Prison Laws

The principal laws governing Pakistan’s criminal justice system, including the penal code, criminal procedure, and prison laws, were enacted under the British colonial rule in India in the mid-nineteenth century, and remain largely unchanged since Pakistan’s independence in 1947. In the words of one prison doctor, under this system the prison superintendent acts as a “viceroy” with near dictatorial power, particularly with regard to access to health care. Colonial-era police and prison laws enable politicians and other powerful individuals to interfere routinely in police and prison operations, sometimes directing officials to grant favors to allies and harass opponents.

Key Recommendations

The reasons for the abysmal and rights-violating conditions in Pakistani jails and prisons are multifaceted and fixing the problems will require broad structural changes. Nonetheless, government at the federal and provincial levels can adopt measures that can begin to bring significant changes in prison conditions and in particular improve prisoners’ access to health care. Until now, successive governments’ failure to allocate adequate resources and to monitor and efficiently utilize them has contributed significantly to the dilapidated state of the prison system. In addition to addressing health care, and ensuring sanitary living conditions and adequate food, the most important reforms include changing bail laws, expediting the trial process, and prioritizing non-custodial sentences to reduce overcrowding.

To achieve these, the government of Pakistan should:

- Reduce overcrowding in Pakistani prisons by: a) enforcing existing laws and early release; b) reforming the bail law to bring it in line with international standards; c) implementing sentencing guidelines for judges to allow bail unless there are reasonable grounds to believe the prisoner would abscond or commit further offenses; c) reforming the sentencing structure for non-violent petty crimes and first-time offenders to include non-custodial alternatives; d) implementing a mechanism of free and adequate legal aid to prisoners who do not have the resources to engage private legal representation; and e) ensuring that prisoners in pre-trial detention are tried as expeditiously as possible, but never detained longer than necessary.

- Increase the number of medical professionals dedicated to health care in prisons, starting with immediately filling all existing vacancies.

- Reform prison rules and practices to bring them in line with international standards such as the Nelson Mandela Rules and the Bangkok Rules and address the specific challenges faced by women and children, including menstrual and reproductive health.

- Establish an independent, efficient, and transparent mechanism to hold prison officials accountable for failure to uphold prisoners’ rights and maintain required standards in prison administration.

- Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and install a mechanism to carry out unannounced inspections at all detention facilities.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report between October 2021 and December 2022 in Punjab and Sindh provinces and the Islamabad capital territory.

Our findings are based on a total of 54 interviews, including with 34 former inmates. We also interviewed lawyers representing detainees and prisoners, legal aid representatives, human rights advocates, journalists, government and prison officials, and family members of those who have been imprisoned. Human Rights Watch also reviewed court decisions, and government and nongovernmental organization (NGO) reports, and conducted a legal analysis of the laws governing Pakistan’s prison system. Even though the report is not an exhaustive survey of the criminal justice system in Pakistan, media investigations, official documents, and human rights reports corroborate our findings on the systemic barriers prisoners face in accessing health care in Pakistani prisons.

In the report, the terms jail and prison are used interchangeably, as Pakistani law makes no distinction between the terms. The term detainees typically refers to individuals in custody who have not been convicted of a criminal offense. Prisoners are incarcerated people who have been convicted of a crime.

Human Rights Watch researchers obtained informed consent from all interview participants. Interviewees were informed about the purpose of interview and that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions they did not feel comfortable answering. No compensation was paid to any of the interviewees. Most of the interviews were conducted in Urdu and Punjabi.

In some cases, we have used pseudonyms, which appear in quotation marks, to anonymize individuals for their security.

On February 28, 2023, Human Rights Watch sent a summary of our findings to the Pakistan government. Human Rights Watch did not receive a response by the time this report went to print.

I. Structure of Pakistan’s Prison System

Pakistan has a federal structure of governance, and Pakistan’s four provinces and two federal territories have primary responsibility for maintaining prisons. However, under article 142(b) of the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan, federal and provincial legislatures have concurrent jurisdictions “to make laws with regards to criminal law, criminal procedure and evidence.”[1] There are separate prison departments in the provinces, but the police service maintains a supervisory role, and the federal government recruits and manages the officer cadre of the police. The prison system in Pakistan is governed by the Pakistan Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure.[2]

Colonial Roots of the Prison System

Many of the present problems associated with the legal structure of Pakistan’s criminal justice system can be traced to the mid-nineteenth century when Pakistan was under British colonial rule.[3] Pakistan’s current prison system evolved through a series of measures enacted between 1835 and 1947.[4] Following a bloody uprising in 1857, British colonial rulers instituted laws governing the police and prisons that were meant to suppress any further resistance. The Police Act of 1861, which created the first colonial police force in British India, established the institution as an instrument of control, not “a politically neutral outfit for fair and just enforcement of law.”[5] The three basic colonial statutes governing prisons – the Prisons Act 1894, the Prisoners’ Act 1900 and the Punjab Borstal Act 1926[6]–were enacted by the colonial government during the decades of British India’s independence struggle. They remain in effect without any significant amendments in the past century. Pakistan’s penal criminal procedure and civil procedure codes also date back to colonial times–1860, 1898, and 1908, respectively.

All these colonial-era laws contribute to a legal framework designed to suppress dissent and protect police and prison officials from accountability. Despite wide recognition by successive Pakistani governments of the need for reform, the process of revamping the police and prison system has been slow. After gaining independence from the British in 1947, Pakistan’s new leaders, like the British colonial authorities before them, wanted to wield their control over the criminal justice system as a tool against political opponents and to intimidate the local population.[7] Since 1947 Pakistan has passed only three significant prison reform laws at the federal level: the Probation of Offenders Ordinance 1960; the Juvenile Justice System Ordinance 2000, which supplements the borstal (juvenile) institutions; and the Mental Health Ordinance 2001, which repealed and replaced the Lunacy Act 1912.[8]

Pakistan Prison Rules 1978

The primary operational document governing prison administration in Pakistan is the Pakistan Prisons Rules 1978, also known as the “Jail Manual.” The Prison Rules have 50 chapters comprising 1,250 rules that provide for classification of prisons; classification of prisoners; duties of the prison’s administrative and medical officers; prisoners’ admission, remission, transfer, and release; and prisoner’s diet, clothing and equipment, and other issues concerning prisoners. Some important features of the Prison Rules are discussed below.

The prisons are classified into four categories.[9] Central prisons exist at a divisional level (covering multiple districts in a province), and each central prison accommodates more than 1,000 prisoners. Special prisons include women’s prisons, borstal (juvenile) institutions, and juvenile training centers. District prisons supposedly accommodate fewer than 1,000 prisoners. The Prison Rules classify prisoners into several categories for the purpose of keeping them separate. These categories include: men and women; juveniles and all others; under-trial and convicts; civil and criminal; and political and non-political.[10]

The inspector general of prisons oversees all prisons in a province, assisted by a deputy inspector general.[11] However, overall responsibility for the security and management of each prison—including all matters relating to discipline, labor, expenditure, punishment, and control—lies with the superintendent, who is required to reside near the prison and visit it at least once every working day and on Sundays.[12] The superintendent is assisted by a deputy superintendent (acting as the chief executive officer of the prison), three or more assistant superintendents, a woman assistant superintendent, and male and female warders.[13]

Answering to the superintendent, a senior medical officer (SMO), assigned by the federal Health Department, oversees the medical and sanitary administration of the prison.[14] The SMO is required to visit the prison and the prison hospital daily, except Fridays and public holidays.[15] The SMO is assisted by one or more junior medical officers and dispensers.[16]

The Pakistan Prison Rules require every prison to have a hospital to treat sick prisoners as out-patients or admitted patients. The rules discourage childbirth in prison but provide for a woman medical officer or midwife in exceptional cases. While children up to the age of six years are allowed to live with their mothers, there is no procedure for removing children once they turn 6, except a vague requirement for the district administration to “arrange for the removal of the child to healthy nursery surroundings through the special societies managing such institutes.”[17] There is no provision in the Prison Rules for conjugal visits by spouses.

Prison Reform Attempts

The 1997 Pakistan Law Commission’s report on “Jail Reforms” was the most significant post-independence attempt at large-scale prison reform in Pakistan. The commission reported that there were 75 prisons in Pakistan’s four provinces and two federal territories with an approved capacity of 34,014 inmates but actual occupancy of 74,483 inmates.[18] Since 1997, Pakistan has constructed around 41 new prisons and expanded several old prisons to be able to accommodate an additional 31,154 inmates, bringing the overcrowding down to 136 percent in 2021.

In 2006, the Pakistan Supreme Court took notice of the abysmal condition of women prisoners after receiving a letter from women prisoners in Central Jail, Lahore detailing their mistreatment.[19] The four wrote that 115 women were lodged in a small place that had capacity for only 50. Following the court’s intervention, the Punjab government approved the appointment of three women doctors in the jails, and a further 12 “Lady Health Visitors,”[20] who were to address any urgent health needs the prisoners or their accompanying children might have. The Supreme Court also ruled that the case would be considered an open one, and that the government should submit periodic reports on prison conditions to the court.

The decision to keep the case open created an important oversight mechanism. For example, in 2015, the court tasked the Federal Ombudsman with inspecting all prisons in Pakistan and report incidents of maladministration.[21] The Ombudsman’s third quarterly report to the Supreme Court in August 2019 noted that in Punjab, separate blocks for female prisoners—supervised by female staff and provided with separate washrooms— had finally been constructed in all 28 prisons in the province.[22] The most recent Ombudsman’s report was submitted in November 2021.

Prison Statistics

As of December 2022, the latest official estimate of the prison population in Pakistan’s four provinces was 88,650 inmates in 116 prisons having an approved capacity of 65,168.[23] This means that each prison, on average, has 764 inmates and is 136 percent overcrowded. The inmate population included 1,399 female and 1,430 juvenile prisoners. In terms of geographical distribution, as of January 2020, Punjab had 41 prisons holding 45,324 prisoners; Sindh had 24 holding 16,315; Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had 20 holding 9,900; and Balochistan had 11 holding 2,122 prisoners.[24]

II. Prisons and Health Care

I have diabetes and a heart condition, and I had to beg and plead the superintendent’s staff to get a tablet of a painkiller. I am a poor man and had no money or connections.

— Kaleem Shah, former prisoner in Karachi.

The abysmal quality of health care in Pakistan’s prisons mirrors deficiencies in access to health care across the country. As of 2018, Pakistan’s health indicators were among the worst in the South Asia region and among peer economies.[25] Pakistan spends only 2.8 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on health, significantly below World Health Organization (WHO) standards.[26] According to a Pakistani healthcare organization, Sehat Kahani, more than 50 percent of Pakistanis do not have access to basic primary healthcare services, and approximately 42 percent have no access to any health coverage.[27] Pakistan does not have a constitutionally protected right to health care. The Constitution notes that the state shall provide “medical relief” in its “Principles of Policy” chapter, but these principles are unenforceable, aspirational objectives of the government.[28] Even the “medical relief” objective is restricted to those citizens who cannot earn their livelihood on account of infirmity, sickness, or unemployment.[29]

Lack of Medical Staff and Healthcare Infrastructure in Pakistani Prisons

The latest official estimate of Pakistan’s prison population, as of November 2021, stands at 88,650 inmates in 116 jails and prisons having officially approved capacity of 65,168.[30] This means that each facility is, on average, 136 percent overcrowded.

For at least a quarter century, human rights advocates and various government commissions have raised the alarm about health conditions in Pakistan’s prisons and jails.

In each prison, medical care is the responsibility of a medical officer from the provincial health department. The level of seniority of the officer varies according to the size and geographical location of the prison. The number of designated posts for medical officers for all prisons in Pakistan was 193, but as of 2020, 105 of these posts were vacant. Moreover, only Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province had approved two posts for dentists and even those were vacant. Similarly, there were 106 approved posts for psychologists — in Punjab and Balochistan, but none in Sindh and KP — but 62 of these were vacant. Punjab’s 41 prisons had only 42 doctors, 6 medical labs and 30 ambulances; KP’s 20 prisons had only 17 doctors, 7 medical labs and 6 ambulances; Balochistan’s 11 prisons had only 9 doctors, 2 labs and 4 ambulances; and Sindh’s 24 prisons had only 17 doctors and 5 labs (figures for ambulances not available for Sindh).[31]

A 2015 report by the Federal Ombudsman of Pakistan reported that Central Jail, Rawalpindi, with an inmate population of 4,748, had a 55-bed hospital with an electrocardiogram (ECG), ultrasound, X-ray and clinical lab facilities but lacked sufficient toilets and medical staff. Out of 709 positions, 193 were vacant, including the positions for a women medical officer, nursing assistant, dispensers, X-ray machine attendant and female dispenser.[32] The report found that Quetta’s district jail with 800 to 900 inmates had a clinic, dispensary and mini lab all operated by one doctor. All serious cases were sent to the nearby civil hospital by the jail’s ambulance.[33] Similarly, the central jail in Haripur, with an inmate population of 1,772, had a 40-bed hospital managed by two medical officers, but lacked an ECG machine, suction machine, X-ray films, oxygen cylinders, hepatitis diagnostic kits, enteric fever/typhoid diagnostic tests, and basic medicines like hydrating salts. The study observed that an orthopedic surgeon from the district hospital was called on to examine the prisoners, most of whom were suffering from osteoporosis due to prolonged confinement in the jail and lack of opportunities for physical exercise.[34]

A 2014 report by the nongovernmental Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), based on inspection of 12 prisons of different types across the four provinces, found that:

The jail hospitals and dispensaries left much to be desired. Of the 12 jails visited by HRCP teams, none had sufficient amount or variety of medication. The dispensaries were critically under-staff and ill-equipped with as few as 3 beds for a prison population of 300. The in-house doctors put the number of patients visiting each day in central prisons at 100 but the supply of medication was severely lacking. Prisoners complained of long waiting lists and inferior quality of medication.[35]

Similar complaints were recorded as far back as 1997, when a report by the Pakistan Law Commission, “Jail Reform,” noted that, although the Pakistan Prison Rules of 1978 required a hospital to be established in each prison for proper medical treatment and the care and nutrition of physically or mentally ill prisoners, hospitals in all prisons were found to be without proper laboratories, equipment, and necessary medicines.[36]

Barriers to Accessing Health Care in Prisons

In January 2022, Saima Farhan, a 35-year-old religious scholar accused of poisoning a neighbor, had abdominal and kidney pains during under-trial imprisonment at Karachi’s Central Jail and could not get medical care. Despite court orders requiring prison officials to provide prompt treatment, she faced repeated delays in getting hospital tests and care and she died in custody.[37] The trial court subsequently acquitted Farhan’s co-accused defendants in the murder case.[38]

The media have reported on deaths and disability resulting from lack of care in prisons. In December 2021, six prisoners at Camp Jail, Lahore, died within 12 days of being taken into custody after their health deteriorated due to lack of central heating, warm clothing, and adequate health care during the harsh winter.[39] In November 2019, the Islamabad High Court received a complaint from a prisoner, Khadim Hussain, in Rawalpindi Jail alleging that his eyesight had been damaged because of the negligence of the jail authorities.[40]

The need for proper medical care for prisoners is particularly important as Pakistan’s prisons house a large and growing proportion of prisoners who are over the age of 60. According to government statistics, as of April 2021 about 2,000 prisoners over the age of 60 were incarcerated in Punjab alone.[41] There are no express provisions in the Pakistan Prison Rules for older prisoners.

Accessing Outside Medical Care

Under international law, an under-trial prisoner should be allowed to be visited and treated by their own doctor or dentist if there is reasonable ground for their application and they are able to pay any expenses incurred.[42]

Pakistani law stipulates that if an inmate—whether under-trial or convicted—is injured or ill, a prison physician should provide medical treatment as a rule. If required, however, and only when the superintendent considers it necessary, the inmate may receive medical treatment from outside physicians or visit or be admitted to an outside hospital.[43] In emergency situations, the superintendent can make the decision and report to the inspector general.[44] However, Human Rights Watch research found that prison officials frequently delay or deny requests for sending inmates to hospitals and specialist treatment even in cases of serious illnesses. Lawyers and former inmates contend that superintendents are very reluctant to allow inmates to visit or stay in outside hospitals because they believe they will use such visits as an excuse to request bail on medical grounds.[45]

According to government figures, as of January 2020 the applications of 245 medically ill prisoners for treatment in a hospital outside the prison were pending with various provincial home departments.[46] The delay in obtaining permission for specialist treatment can have disastrous medical consequences for prisoners. Abdul Basit, a former administrator at a medical college, was convicted and sentenced to death for murder in 2009. On August 1, 2010, Basit contracted tuberculous meningitis while in Faisalabad Central Jail. His family requested that he be sent for specialist treatment, but due to the apparent negligence of jail authorities, his condition went undiagnosed for a month, by which time his spine was irreversibly damaged.[47] Since then Basit, who remains on death row, has been paralyzed from the waist down.[48]

Raza, 39, who is diabetic, was imprisoned in a Punjab prison for six months in 2021 for alleged financial fraud. He said:

I have had diabetes since I was a child and that has also resulted in my being overweight. I needed insulin and each time I faced resistance from the prison staff. They made fun of me saying that the only condition that I had was being “fat” and one year of prison food will make all my health issues go away. I finally managed to get a regular supply of insulin by bribing a member of the jail staff.[49]

Bilal, 46, has spent four years in a prison in Punjab. He has a high uric acid condition, which requires that he avoid fatty foods with high oil and protein content, or his feet swell up causing pain and difficulty in walking. He described making repeated requests to not be given the standard meals of pulses and meat “floating in oil.” However, prison authorities refused his requests and said that “this is not a hotel.” The only choice that he had was to either starve or bribe someone to get food delivered from his home.[50]

Muhammad Shabbir, 39, is a political party activist who has spent a total of three years in Karachi prisons. His last incarceration was from March to November 2019 on charges of assault. He has never been convicted of any crime. Shabbir has developed a permanent limp in his right leg due to a prior injury hindering his mobility. He said that prison staff refused to give him a crutch:

Prison in Pakistan is a nightmare for almost everyone, however for people with disabilities the torture is never-ending. I asked for a crutch in prison, however my request was denied because the authorities claimed that I could use it as a weapon to hit someone. I had to depend on the charity of fellow inmates often to hold my balance. My leg hurts constantly, and I was given painkillers sometimes and refused at other times on the grounds that I am addicted to painkillers.[51]

Corruption

Extortion by prison staff and other forms of corruption are rampant in the Pakistani prison system. A September 2022 report by the National Commission of Human Rights (NCHR), an independent statutory body, highlighted the scale of corruption and extortion in Adiala prison in Rawalpindi district in Punjab.[52] According to the report, 74 percent of the prisoners the NCHR team interviewed described torture and 100 percent described financial extortion for everything the jail was supposed to provide, such as food and medicines.[53]

While access to health care in Pakistani prisons for most prisoners falls far short of international and domestic standards, a small percentage of influential and wealthy prisoners who claim to be unwell are transferred to outside hospitals to spend their prison term in comfort. Kaleem Shah, who spent two years in a Karachi prison from 2019-2021, said:

One rich prisoner spent months in a hospital outside of prison because he apparently had “backache.” He was completely fit, and it was a joke. We knew of stories of him holding parties in his “hospital.” Later we found out that his family had bought the hospital he was being kept at, so essentially, he spent that time at a hotel while people die in prison because the prison staff doesn’t believe that they are ill and they don’t get medical treatment in time.[54]

The case is not unique. In January 2022, the Sindh government ordered an inquiry into the “prolonged and unjustified hospitalization” at public and private hospitals of 21 prisoners. A prison official speaking on the condition of anonymity said that almost all of these prisoners were wealthy and influential, and procured fake medical reports to persuade officials to send them to outside hospitals.[55] The prisoners had to pay significant bribe money to prison authorities and administrative officials at the public and private health facilities in order to be transferred.[56] In 2019, the Sindh High Court in Karachi highlighted the class divide in access to health care for wealthy or influential persons accused of a crime:

You can generally obtain medical certificates/opinions to meet your requirements in order to enable you to be transferred from prison to hospitals outside of the jail premises where you can enjoy much better facilities such as free access to mobile phones, air conditioning, cable television, better food, unlimited visitation rights, a greater level of freedom of movement within hospital environment etc., with the knock-on effect of often delaying the trial due to nonappearance to the disadvantage of those who are locked up in jail or whose bail has been declined. This in our view tends to point prima facie to discrimination under Article 25 of the Constitution [on equality of citizens] and is a poor reflection of the Dr’s [sic] and medical boards who are tasked with making honest and accurate assessments of a prisoner’s health who claims to be unwell.[57]

Impact of Floods on Prison Infrastructure

Prisoners are among the most vulnerable segments of Pakistani society to natural disasters because decades of neglect, underfunding, and corruption has left prison infrastructure in poor repair. Cataclysmic flooding in Pakistan in July-August 2022, triggered by unprecedented monsoon rainfall and glacial melting, killed over 1,100 people and destroyed hundreds of thousands of homes and millions of acres of crops, affecting more than 33 million Pakistanis and causing billions of dollars in damage.[58] There were reports of flooding causing severe damage to some prison facilities and official prison records.

In Sindh, the province worst affected by the flooding, 19 prison facilities were located in flood-affected areas with a total prison population of 8,542.[59] Sindh’s Prison & Corrections Service Act and Rules 2019 allows for the transfer and temporary accommodation of prisoners in case of emergencies.[60] Maliha Zia, a lawyer working on prison rights in Sindh, said that, “The prison administration had to cope with the flood damages on their own. The Prisons Department has faced a huge challenge in terms of prisoners shifting to the other prisons – there was no transportation and [no] security teams available for this purpose.”[61]

Flooding also severely damaged Pakistan’s crumbling healthcare infrastructure. In Sindh province, more than 1000 health facilities were fully or partially destroyed. Another 198 health facilities were damaged in Balochistan province. The extensive damage to roads and communication networks further hindered access to clinics and hospitals.[62]

III. Access to Food, Water and Sanitation

The water given to us was the [unfiltered] water used for washing dishes and watering plants. The water in the bowls in our cells would sometime have dead mosquitoes and flies floating in it.

— A former prisoner in Faisalabad

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, known as the Nelson Mandela Rules, safeguard the right to food for prisoners.[63] Pakistan’s prison manual mandates that the government should “take all such measures as may be necessary to ensure that every prisoner is at all times so supplied with food and drink as to maintain him in good physical health and vigor.”[64]

In practice, Pakistani prisoners’ access to healthy food and clean water remains a widespread problem. Government officials often say they cannot provide adequate food to prisoners because they do not have enough resources in their budgets to do so. In 2020, the deputy inspector general of prisons of Rawalpindi lamented that the provision of food for over 50,000 prisoners in the province was very difficult to do under their current budget.[65]

A serving police officer who spoke to Human Rights Watch on condition of anonymity also said that inadequate resources were to blame for insufficient food supplies:

The primary cause of [poor] prison conditions in Pakistan is the lack of adequate financial resources. The lack of resources leads to corruption which in turns lead to a lack of trust by the prisoners – it is a vicious cycle. The budgetary allocation for the food for prisoners is not nearly sufficient and hence there is no choice but to encourage people to have food delivered from their homes as far as possible, so those who are affluent don’t take up resources which should be used for those who have no choice. But yes, it does create a class system in prison with the rich prisoners eating better food than the poor prisoners.[66]

However, prisoners and advocates for prison reform dispute the idea that a resource deficiency is the primary reason for substandard prison conditions and corruption. Muhammad Aqeel, a Lahore based lawyer, said:

Corruption in the prison system is almost entirely legalized and has created an incentive structure to continue the corruption. One example is creating the cycle of scarcity and then forcing prisoners to buy food items at inflated prices.[67]

As an example, Aqeel said prison managers sell fruit to inmates and then invoice the government for the cost as though the fruit was provided to the inmates free of charge.[68]

Shumail Ahmed, who was in prison in Lahore from 2018-2020, described the discrepancy between the officially designated menu for prisoners, which listed chicken and vegetables, presumably claimed as expenses by prison officials, and the cheaper “watered-down” pulses (daal) along with a single piece of bread (roti) that was actually served to the inmates.[69]

Rehana Rasheed, whose husband had been in prison in Karachi for the past four years on drug-related charges, said that her husband had lost 20 kilograms in prison.[70] She had to seek special permission to bring homemade food for him, and had to bribe the staff on each of her visits. It "drained all our income," she said.[71]

The Covid-19 outbreak made access to food supplies even more challenging. Given that many families were unable to go to the prison to bring food because of restrictions on movement, prisoners who depended on this supply were cut off. As a result, inmates were obliged to purchase food items from the prison commissary. Prison canteens inflated their prices substantially during the pandemic.[72] Additionally, many inmates usually relied on their families to bring essential supplies with them including more nutritious or diverse food than was available at the prisons and necessary medication.[73]

Human Rights Watch interviewed former inmates and government officials who described the lack of clean drinking water. Tap water in Pakistan is not suitable for drinking. Although water filtration systems should be installed to provide safe, drinking water, these are lacking in many prisons. One prisoner who spent three months in Faisalabad prison said, “If there was a water filter, we never saw it. Almost everyone had stomach and water-related issues.[74]

Pakistan’s groundwater has a high arsenic content. A 2017 study of nearly 1200 groundwater samples found up to 60 million people at risk from chemical arsenic.[75]

Conditions in Pakistani prisons are notoriously unsanitary. According to rule 381 of the 1978 Pakistan Prisons Rules, detainees are generally responsible for keeping their own cells clean.[76] However, rule 763 of the Prisons Rules also specifies that “the wards or cells occupied by prisoners suffering from infectious or contagious diseases, shall be whitewashed and disinfected as often as may be directed by the Medical Officer.”[77]

In highly overcrowded cells, it is not reasonable to expect prisoners to keep the cells clean. One former prisoner said, “the responsibility to clean the cell often falls to the youngest and weakest in the cell but it is useless for anyone to clean the cell because it would be dirty again in 15 minutes.”[78] Lice, fleas, scabies, and skin diseases are common in prisons, and prisoners described infestations of rats and lizards in their cells.

In a March 2020 judgment, the Islamabad High Court noted the “unprecedented and grave conditions prevailing in the prisons across the country,” and stated that “[t]he living conditions and the treatment of prisoners in overflowing and inadequately equipped prisons has raised serious constitutional and human rights concerns.” The court ruled that, “A prisoner who is held in custody in an overcrowded prison, having lack of sanitation, [is] tantamount to cruel and inhuman treatment for which the State ought to be accountable because it amounts to a breach of its fiduciary duty of care.”[79] However, the court decision did not result in any significant prison reform efforts.

The prison medical officer in each prison is responsible for physical and mental health of the prisoners and the general hygiene of prison premises, carrying out at least a weekly inspection to ensure that, “nothing exists therein which is likely to be injurious to the health of the prisoners.”[80] However, the work of the medical officer is subject to supervision and direct control of the jail superintendent. One medical officer for a prison in a district of Punjab said:

The superintendent is practically the viceroy of the colony which is the prison, and anything and everything has to be approved by him. I am legally responsible for ensuring that the prison has supplies for medicines and also that precautions are taken to prevent overcrowding. However, in practice, even a tablet of Panadol [pain reliever] has to be signed off on by the superintendent. As far as overcrowding, drainage and water supply inspections are concerned, I have almost no authority.[81]

Another former medical officer echoed this and said that when he demanded clean water for prisoners, he was told by the superintendent that “these are criminals who are being punished. Stop treating them as if they were on vacation.”[82]

In 2013, the director of the Punjab Tuberculosis Control Programme said that tuberculosis spread 29 percent faster in jails than in the general population due to overcrowding and incidences of water-borne diseases, and provision of counterfeit medicines were also contributing factors.[83]

IV. Overcrowding and Bail Reform

It was impossible for all of us to lie down in the cell at the same time because there was simply not enough space.

— Jalal, a former prisoner in Lahore

Unsanitary and unhygienic conditions are widespread in Pakistani prisons. Overcrowding exacerbates the risks.

In some prisons between six and 15 prisoners may occupy a single prison cell built to hold a maximum of three prisoners. Jalal was 19-years-old when he was arrested in connection with a case of theft and sent to prison in Lahore in 2019. He remained in prison for 35 days in a cell with six other people. He said:

I was there in summer [June and July] and we had one fan which only worked half the time due to power outages. In the Lahore heat, with the perspiration and sweat of seven people in a tiny room, it was like being baked alive. I was dizzy and sometimes delirious due to the heat. I collapsed and was unconscious three times and was given water, asked to take a shower and “not be dramatic.”

The experience scarred Jalal physically and mentally:

I lost six kilograms in one month, permanently lost my hair and had bags under eyes making me almost unrecognizable by the time I was released. The police said that they had mistakenly arrested me and had no evidence. But the experience has scarred me for life. Two people in my cell had been in prison for over seven years awaiting the results of their appeal, I can’t imagine them ever recovering from this hellish experience even if they are released.[84]

Shafiq, 33, who was in a prison in Lahore for four weeks in 2021, said, “the room was so clogged at night that it was almost impossible to get up and go to the bathroom without stepping on people’s heads and the only option was to wait till morning.”[85]

Irfanullah, 22, was arrested in Karachi in March 2022 on suspicion of theft of a motorcycle. He spent three weeks in prison. He developed a serious skin allergy and according to him his entire body was "red" and the urge to itch himself was so strong that he had to "keep his hands clenched tightly together all night" to prevent him from waking up bleeding from scratching all night.[86] Irfanullah shared a small cell with five people and according to him there was barely any room for "air to pass" between them when they slept. He said, "almost everyone in prison was itching themselves all the time, and it was just that in my case the rash was particularly bad."[87]

In September 2022, a government report documenting the conditions in Adiala prison in Rawalpindi district found extreme overcrowding with 6,098 inmates housed in a prison with a maximum capacity of 2,174, a severe shortage of medical personnel, an inadequate medical budget only 1/7 of the required budget, inedible food, and “a system steeped in financial extortion to get access to basic rights and facilities within the jail.”[88]

Pre-Trial Detention

The major causes of overcrowding in prisons are the prevalence of pre-trial detention; the propensity of police to arrest and detain suspects as a matter of default; difficulty of obtaining bail; and the reluctance of judges to impose non-custodial sentences even in cases that warrant them. The reluctance of the courts to grant bail exists as a matter of practice despite the Pakistani Criminal Procedure Code allowing for bail for most offenses, including serious ones.

Pakistan’s police have expansive powers of arrest and detention. The police are authorized to arrest without a warrant any person against whom there is “reasonable suspicion” of being involved or “concerned in” certain types of criminal offenses, or against whom there exists a “reasonable complaint” or “credible information” of such involvement. This includes individuals who are in possession of anything “which may reasonably be suspected to be stolen property.”[89] In addition, police can also arrest without a warrant a person whom they know or suspect of “designing” to commit certain types of offenses.[90]

To provide protection from arbitrary arrest and detention, as well as abuses in custody, the law also specifies that when the police arrest without a warrant, the arrested person must be produced before a magistrate within 24 hours.[91] In the event that the investigation cannot be completed in 24 hours, and there is reason to believe that the accusation is “well-founded,” the police can produce the accused in front of the magistrate and get authorization for further detention or physical remand. Magistrates can authorize physical remand for up to 15 days.[92] Discussions with NGOs and accounts from many former detainees indicate that police routinely abuse their powers, and arbitrarily arrest and detain people.[93]

International human rights law provides that pre-trial restrictions on criminal suspects must be consistent with the right to liberty, the presumption of innocence, and the right to equality under the law.[94] Pre-trial detention imposed on suspects as a means of punishment, to pressure confession, or because a defendant cannot afford bail is inconsistent with those rights.[95] Yet this routinely happens in Pakistan.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Pakistan ratified in 2010, upholds the right to liberty: “Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person.”[96] A person’s liberty may not be curtailed arbitrarily, either through arbitrary laws or through the arbitrary enforcement of the law. To comply with the covenant, “deprivation of liberty must be authorized by law” and “must not be manifestly unproportional, unjust or unpredictable.”[97]

Reforming the Bail System

The ICCPR provides for bail for individuals in pre-trial detention: “It should not be the general rule that persons awaiting trial shall not be detained in custody, but release may be subject to guarantees to appear for trial.”[98] Pre-trial detention also compromises the presumption of innocence, affirmed in the ICCPR as necessary for a fair trial: “Everyone charged with a criminal offence shall have the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law.”[99] Pakistan’s Supreme Court has held that it “is crystal clear that in bailable offences [bail] is a right and not favour.” However, in practice, Pakistani courts continue to be reluctant to grant bail.

A former judge told Human Rights Watch:

The single most urgent and effective prison reform measure in Pakistan is reforming the practice of granting bail. The denial of bail is used as a tool of punishment and the grant of bail is viewed as a favor. The prison population in Pakistan will be halved if the courts decide to grant bail keeping in view international practices.[100]

Several other problems in the criminal justice system contribute to massive overcrowding. Police routinely fail to submit investigation reports within the 14-day period prescribed by law, and completion of the investigation is usually subject to further delays-often lasting more than a year. This results in detainees being kept in custody for a long time, sometimes years.

The Criminal Procedure Code states that bail amounts should not be excessive, but judges routinely set bail well beyond the reach of detainees' families, which disproportionately harms the poorest. Court hearings are frequently adjourned, for a variety of reasons. These include the failure of prison authorities to produce detainees, police disregard of summons, the absence of adequate security and travel arrangements for witnesses, and administrative incompetence in scheduling hearings. The lack of availability of state-provided legal aid often results in delays in court proceedings and consequently in unnecessary detentions.

On March 14, 2020, the chief justice of the Islamabad High Court, in the landmark case Khadim Hussain v. Secretary, Ministry of Human Rights, held that:

overcrowding of prisons, failure to segregate prisoners in accordance with the provisions of the Jail Manual, inhuman and degrading treatment, denial of prompt and timely health assistance, denial of access to proper legal advice and courts, is unconstitutional and a violation of the commitments of the State of Pakistan under the ratified conventions and the constitutionally guaranteed rights. [101]

The court directed the federal government to make the Public Defender and Legal Aid Office Act 2009 and the Mental Health Ordinance 2001 operational to enable “the poor and mentally disordered persons” to have effective access to the right of proper legal advice and the courts.[102] However, legal experts and lawyers told Human Rights Watch that no significant changes have occurred as a result of the reform attempt.

Setting bail beyond the reach of prisoners can result in prolonged detention. Imad Qamar, a lawyer based in Karachi, said that one of his clients, a rickshaw driver, had been falsely implicated in a criminal case of assault:

It took one year for him to be granted bail and the legal process by then had completely wiped out his meager financial resources. The judge set his bail at PKR 500,000 [US$2,320]. His monthly income before going to prison was PKR 20,000 [$93]. By the time the bail was granted he was already in debt and the family had no money or assets. He remained in prison for one month for non-payment of bail bonds. Finally, his brother-in-law pledged his house as surety to bail him out. [103]

V. Access to Mental Health Care

I have a history of clinical depression and was arrested on completely fabricated charges and kept in solitary confinement for the first three weeks.

— Kashif Rana, doctor and former prisoner

Multiple research studies have highlighted the widespread prevalence of psychosocial disabilities – mental health conditions – among Pakistani prisoners. This marginalized group is particularly at risk of abuse.

A 2014 study conducted among adult male prisoners in Lahore showed that the prevalence of depression in this inmate population was 85 percent. “Of the total, 30 percent had mild depression, 20 percent had moderate depression and 35 percent had severe depression.”[104] Similarly, a 2012 study found that 59 percent of the female inmates at the Peshawar prison experienced depression.[105]

In 2018, two NGOs, the Legal Aid Society and Sehat Kahani, were given access to carry out research and provide counseling to women prisoners in Karachi Central Prison. They found that over 65 percent of their sample met the criteria for one or more mental health conditions, the most common being depression, generalized anxiety or panic attacks, and post-traumatic stress.[106]

Haya Zahid, the secretary for the Prison Rights Committee, Sindh, said:

The Sindh government has taken important and progressive steps in prisoner rights, however problems remain. One significant problem is the medical officers who are deputed to prisons have no training [in] correctional medicine [heath care for prison populations] and try and treat patients without understanding the context. This problem is particularly exacerbated in issues of mental health.[107]

According to the Justice Project Pakistan, a Pakistani NGO, as of December 2020 there were approximately 4,688 prisoners on death row in Pakistan. The figures for those prisoners with psychosocial disabilities are not known; as of 2021, Punjab province had registered 188 death-row inmates with mental health conditions.[108] The actual numbers in Punjab alone could be much higher. According to a prison medical officer in Punjab:

Diagnosis of mental health issues is only done when a prisoner is violent, and mental health conditions which do not manifest themselves in violence either directed to themselves or others often don’t get diagnosed at all.[109]

Health professionals and rights activists have long advocated for full-time mental health service providers in prisons, and training for prison staff on mental health and suicide prevention. Several people told Human Rights Watch that ignorance on mental health in Pakistani society in general and particularly in the criminal justice system is prevalent in the prison system. Kashif Rana, 41, a doctor who spent four months in prison in 2018, said: “I was depressed and suicidal. I spoke to the superintendent and requested professional help and was told, ‘[E]veryone here is depressed. Even I am depressed. You should start praying.’”[110]

The Pakistan Prison Rules mandate that every prisoner be medically examined by a medical officer within 24 hours of being admitted to prison, with observations regarding physical and mental health recorded.[111] However, the medical officer is only required to give an assessment on a scale of “good, indifferent, or bad.”[112] The Prison Rules do not specify the procedure to be followed when the prisoner has a mental health condition. In practice the medical examination is perfunctory and hurried. Most former inmates interviewed had no recollection of a mental health assessment. Said one jail superintendent, “there is no full-time psychiatrist available at the prison premises and the medical officers only notice if there is something observably or unavoidably wrong with a prisoner and perhaps then an observation can be made for a visiting psychiatrist to check in the future.”[113]

Chapter 18 of the Pakistan Prison Rules deals with “mental patients.” The rules divide “criminal mental patients” into four categories: those sent to prison for a mental health assessment; defendants whose trial and investigations have been suspended due to “incapacity”; defendants acquitted on the grounds of “insanity” but still detained in “safe custody”; and convicted prisoners who become “mentally unwell” in prison.[114] Under section 466 of the Criminal Procedure Code, detainees may be detained in a psychiatric hospital for involuntary treatment until the institution signs off on their recovery. Such forcible treatment is a violation of fundamental human rights.[115]

For prisoners who require a mental health assessment, the medical officer has the discretion to decide if they will be detained in the prison hospital or not. The prison hospitals however do not have staff trained to support prisoners with psychosocial disabilities.

Prisoners who develop a mental health condition while in prison can be transferred to a mental health institution with the superintendent’s approval. One visiting prison psychiatrist said:

There is an inherent mistrust of mental health assessments which require transferring patients out of the prison. Often, the prisoners with mental health issues are ignored, their conditions downplayed, [or] … treat[ed] with sedatives and painkillers up to the point that the condition worsens to the point of harm or self-harm.[116]

Prisoners with mental health conditions are more at risk of abuse and mistreatment from both prison authorities and fellow inmates. For example, Khizar Hayat, a former policeman, was arrested by the police in 2001 for allegedly killing a colleague.[117] A court sentenced Hayat to death in 2003. In 2008, prison doctors diagnosed Hayat with paranoid schizophrenia and prison officials prescribed him antipsychotic medication ever since.[118] His jail records show that in 2009 he was admitted to a public hospital with severe head injuries and required an urgent operation after being attacked by his cellmates.[119] His lawyers said that he was frequently attacked. The lawyers and Hayat’s mother requested in 2009 that he should be moved to a proper medical facility, but the request was deferred. Hayat was scheduled to be executed twice, and both times the execution was postponed at the last minute.[120] According to his lawyers, by 2012 Hayat experienced delusions to such an extent that prison authorities isolated him from the general prison population by moving him to the prison hospital, purportedly for his safety, but without his consent.[121] He remains incarcerated.

Human Rights Watch research internationally has found that prisoners with disabilities are often viewed as easy targets and as a result are at serious risk of violence and abuse, including bullying and harassment, and assault.[122]

Under the Pakistan Prison Rules, jail authorities may separate prisoners suspected to be or have been declared to be “mentally unwell,” from other prisoners on the grounds that “mental patients [are] to be considered dangerous until certified harmless” by a medical officer.[123] A Lahore-based psychiatrist said that, “the language of the Prison Rules displays the harmful and presumptuous attitude of the penal system in Pakistan towards anyone with a mental illness and disincentivizes people to come forward with psychological issues unless completely unavoidable or impossible to conceal.”[124]

Under the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, which Pakistan ratified in 2011, a person with a disability who is convicted of a crime and sentenced to time in prison should be treated the same other prisoners, except that they must be provided reasonable accommodations (including support services) for their disability. They should never be segregated or diverted to alternative systems.[125]

The Pakistan Prison Rules mandate that the provincial inspector general of prisons along with medical experts should visit prisoners with psychosocial disabilities every six months and assess the care.[126] In practice, the visits have not occurred as required and visits that occur are often cursory.[127]

A 2018 research paper documented the situation of one prisoner:

In a criminal case involving a schizophrenic prisoner, it was argued that due to schizophrenia’s complexity of symptoms and potentially deteriorating course, the defendant had very little chances of recovering and it was abnormal to desire him to do so. In order to ascertain the defendant’s mental state, he was supposed to be examined periodically and the reports were to be sent to court. However, there were no systematic reports or re-assessments taking place to assess his mental condition. Due to this reason, it was difficult to evaluate any improvement, if at all, in the mental health of the prisoner and his trial remained suspended. Not only was he subjected to prolonged detention, a violation of his fair trial guarantee, but he was also not being … properly [supported].[128]

The prevalence of the use of solitary confinement in Pakistani prisons poses additional risks for people with psychosocial disabilities. Isolation can be psychologically damaging to any prisoner causing anxiety, depression, anger, obsessive thoughts, paranoia, and psychosis. Its effects can be particularly detrimental for people with psychosocial disabilities.

The stress of a closed and heavily monitored environment, absence of meaningful social contact, and lack of activity can exacerbate mental health conditions and have long-term adverse effects on the mental well-being of people with psychosocial disabilities. Frequently, people with psychosocial or cognitive disabilities can decompensate in solitary confinement, attempting suicide or requiring emergency psychosocial support or psychiatric hospitalization.

Juan Mendez, the former UN special rapporteur on torture, stated that the imposition of solitary confinement “of any duration, on persons with mental disabilities is cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.” He called on governments to abolish it for prisoners with psychosocial or cognitive disabilities and that “the longer the duration of solitary confinement or the greater the uncertainty regarding the length of time, the greater the risk of serious and irreparable harm to the inmate that may constitute cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment or even torture.”[129]

VI. Concerns for Women and Girls in Prison

Women in Pakistani prisons face mistreatment and abuse on a massive scale, reflecting the discrimination and vulnerability to abuse faced by women in Pakistani society generally. Human Rights Watch interviewed nine women who had been imprisoned.

In 2020, Pakistan’s Human Rights Ministry issued a report documenting poor conditions and barriers to adequate medical care faced by women prisoners.[130] The report, “Plight of Women in Pakistan’s Prisons,” submitted to the prime minister on August 26, 2020, found that Pakistan’s prison laws did not meet international standards and that officials often ignore laws designed to protect women prisoners.[131] Of the 1,121 women in prison as of mid-2020, 66 percent had not been convicted of any offense and were detained prior to trial or while awaiting their trial’s conclusion. More than 300 women were detained in facilities outside the districts where they lived, making family visits nearly impossible. The prisoners included 46 women over the age of 60 and 10 girls under 18. Currently, only 24 female health workers are available to provide full-time care to women and girls in prisons across the country.

The committee that produced the report found that prison staff routinely failed to observe appropriate protections against the spread of the virus that causes Covid-19. Prison staff failed to put social distancing measures in place or require prisoners and staff to wear masks. The committee urged comprehensive medical screening for all entering prisoners.[132]

In September 2020, then-Prime Minister Imran Khan ordered officials to carry out a Supreme Court decision compelling the release of women prisoners to reduce prison congestion and limit the spread of Covid-19.[133] The women to be released were those awaiting trial for minor offenses or had already served most of their prison terms. Khan also asked for “immediate reports on foreign women prisoners and women on death row for humanitarian consideration” for possible release. Despite these instructions, as of March 2023, no women prisoners had been released.

Children who accompany their mothers in prison faced additional risks. As of September 2020, 134 women had children with them in prison, some as old as 9 and 10, despite the legal limit of 5 years. Altogether at least 195 children were housed in prisons.[134] A critical lack of funding in the prison healthcare system has meant that mothers whose children are with them in prison often lack essential health care, leaving both the women and the children at risk of contracting infections or experiencing other health problems. One prisoner reported that her child, who had a developmental disability, was not offered any support services or medical care despite the prisoner’s repeated requests during her six years of incarceration.[135]

In line with international standards, the committee recommended reducing the proportion of prisoners held in pretrial detention, allowing women to be detained close to their homes to facilitate family visits, and reducing the number of women and girls in prison by developing alternative sentencing options and non-custodial measures for women and girls.[136] The committee also said that individual cases should be reviewed to identify possible human rights violations and humanitarian needs, and recommended more training of prison staff, resources, and policies to address the mental health needs of women in prison, and development of post-release programs to help women and girls reintegrate into the community.[137]

The committee provided a detailed analysis of the extent to which Pakistan’s national and provincial laws comply with the UN “Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures for Women Offenders” (the “Bangkok Rules”).[138] The committee found important gaps requiring reform in the provincial and national legislative framework. For instance, only Sindh province had enacted prison rules that complied with international standards.[139]

Under the Bangkok Rules, non-custodial alternatives to custody should be preferred where possible if someone facing imprisonment is pregnant or has sole child-caring responsibilities. Children accompanying their mothers should receive suitable health care, at least equivalent to that available in the community.[140] The decision as to whether a child is to accompany their mother in prison or be separated from their mother should be based on individual assessments and the best interests of the child. Children in prison with their mother should never be treated as prisoners, and their environment needs to be as close as possible to that of children outside prison.[141]

Lawyers and rights activists said that women prisoners are especially vulnerable to being abused by male prison guards, including sexual assault, rape, and being pressured to engage in sex in exchange for food or favors. A lawyer based in Islamabad said:

The stigma attached to women being in prison is very high and often leads to women prisoners being abandoned by their families. This increases their vulnerability further and enables and encourages abusive behavior, including sexual violence. Women arrested for sex work form a significant group of the detainees and are most at risk of sexual violence and abuse.[142]

Women’s menstruation hygiene remains an area of particular concern and neglect.[143] Three former prisoners said that sanitary pads were not routinely provided.[144] A woman former police official said that “one fundamental problem is viewing sanitary napkins as a luxury item or a medical supply rather than a necessity.”[145] Lack of access to sanitary napkins, soap and clean water puts menstruating women at a higher risk of infection. The lack of women in supervisory and senior positions in the prison administration also exacerbates the problem as in a deeply patriarchal society where women prisoners will be much more comfortable speaking about personal issues with a woman official. In some cases, sanitary pads have to be bought in prison at exorbitant rates.[146] The Pakistan Prison Rules include provisions for women's hygiene, but do not address menstruation specifically.

Razia Ghafoor, 37, spent three years in a prison in Lahore, Punjab after being convicted for a drug trafficking offense between 2016-19. She said:

Throughout my stay in prison, I suffered from acute migraines and hormonal issues causing pains and irregular menstruation cycles. I was not allowed to meet a specialist even once and was only given a painkiller. It is extremely difficult for us to speak about menstruation to a male prison official due to social taboos and embarrassment. Women prisoners are treated the worst because in Pakistan they are abandoned by their families, and no one comes to visit them and hence the prison authorities know that no one is willing to pay any [bribe] money for their better treatment.[147]

Kiran, 24, was arrested for “solicitation” at a dance performance in Sahiwal district, Punjab, and kept in custody for three weeks in 2019. After this detention the police then dropped all charges. She said:

It seemed every one of the officials thought that I was “fair game” for lewd comments, brushing their bodies against mine, touching me inappropriately. It was hell. I felt I was a piece of meat on display in a butcher shop. Women who are arrested in Pakistan have to face this since everyone assumes that they are of a “loose character” and have no morals. The prison water was filthy, and the women bathrooms were rarely cleaned. My stomach hurt throughout my time in prison but there was no one to complain to. I am estranged from my family so there was no one to help. It was only because I could bribe the police to drop the charges that I finally managed to escape.[148]

Ambreen Shah, 41, was arrested in Rawalpindi district on charges of financial embezzlement and stayed in prison for 10 days in 2017. She was subsequently acquitted. Shah said:

I got my periods on my first day in prison. I had heavy bleeding and stomach cramps. The sanitary pads available were not clean and I had to beg for them to allow my family to bring me sanitary pads. My husband had to pay a prison staff member to be allowed to give me pads and medicines. It was the most humiliating experience of my life.[149]

A 2015 report by the Punjab Commission on Status of Women noted that the:

[l]ack of proper medical facilities for women prisoners is a problem common to all prisons of the Punjab. While male doctors are employed in all prisons, qualified full time Women Medical Officers were either not appointed or had not joined; … do not reside in Prison Housing; or are found to be absent and reportedly negligent.… Since prisons are not equipped to deal with complicated cases of any nature, including gynecological issues, women are often referred to District Headquarters Hospitals, a process that is lengthy, cumbersome, and potentially even harmful for a person in need of immediate medical attention.[150]

A 2008 study of the dietary scales for women and children given in the Pakistan Prison Rules concluded that the diet of women prisoners was deficient in iron (only 42 percent adequate) and that of children was lacking in protein, energy, calcium, and iron (adequacy ranging from 4 percent to 75 percent).[151]

Pregnant prisoners require special medical attention, and the Prison Rules direct the medical officer “to draw up a special diet scale, to include milk, fresh vegetables, fruit or any other article of diet…, the quantities of these according to necessity.”[152]

Childbirth also adds to the complications and hardship women prisoners face. In larger cities, prisoners are transferred to hospitals for childbirth, however in smaller districts a midwife visits the prison to assist with childbirth.[153] The qualification and training credentials of visiting midwives are often not verified.

Women’s prisons in Karachi are not overcrowded and are actually below capacity, but still have healthcare problems. According to an official from the Sindh Prisoner Rights Committee:

Prisons need better and more medical facilities and personnel. Medical officers are available for women prisoners, however [they] have no training in correctional medicine. The concept of correctional medicine is alien here.[154]

According to the Legal Aid Office (LAO), an organization working for prisoner rights in Sindh, while conditions for women in prison in Karachi are better than in other prisons in the country, systemic problems remain. One of the primary problems is the lack of adequate legal aid. A 2018 survey by LAO found that 71 percent of women prisoners in Karachi were illiterate.[155] This coupled with poverty and insufficient legal aid meant that most were unaware of their rights. A Sindh Home department official said:

Women prisoners are the most marginalized, and most of them don't understand the legal process. This makes them additionally vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. They are told by jail authorities that even basic rights are a result of benevolence and can be taken away at any time.[156]

Foreigners in Pakistani Prisons

In December 2022, media reports showing photos of Afghan children in Karachi prison sparked outrage on social media.[157] The National Commission for Human Rights (NCHR) dispatched a fact-finding mission to the Karachi Women’s Prison and found 139 Afghan women along with 165 Afghan children incarcerated there. The majority of the women were under trial on charges of immigration law violations—the primary reason Afghans are detained in Pakistan. [158] Only 25 percent of the Afghan detainees had access to legal representation.[159]

Rukaya Bibi, 65, had travelled to Pakistan to see a doctor. She told NCHR officials that because it was difficult to get medical care in Afghanistan, her family had brought her to Pakistan for a diagnosis and treatment. Rukaya was arrested for not having proper travel documents before she could get care.[160] She said she had planned to return home to Afghanistan once her treatment concluded. Her daughter, who had accompanied her on the trip, was also arrested. She is now confined at an overcapacity Karachi women prison and possibly at a greater risk of illness and infection.

Pakistani authorities have not made detailed information available on foreigners imprisoned in the country’s prisons. A December 2021 news report found at least 34 foreign prisoners in Punjab province had served out their sentence but remained in prison due to unwillingness from their home countries to pursue their release.[161] In 2018, the National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA) conducted a study on overcrowding in prisons and found more than 1100 foreign prisoners incarcerated across the country.[162]