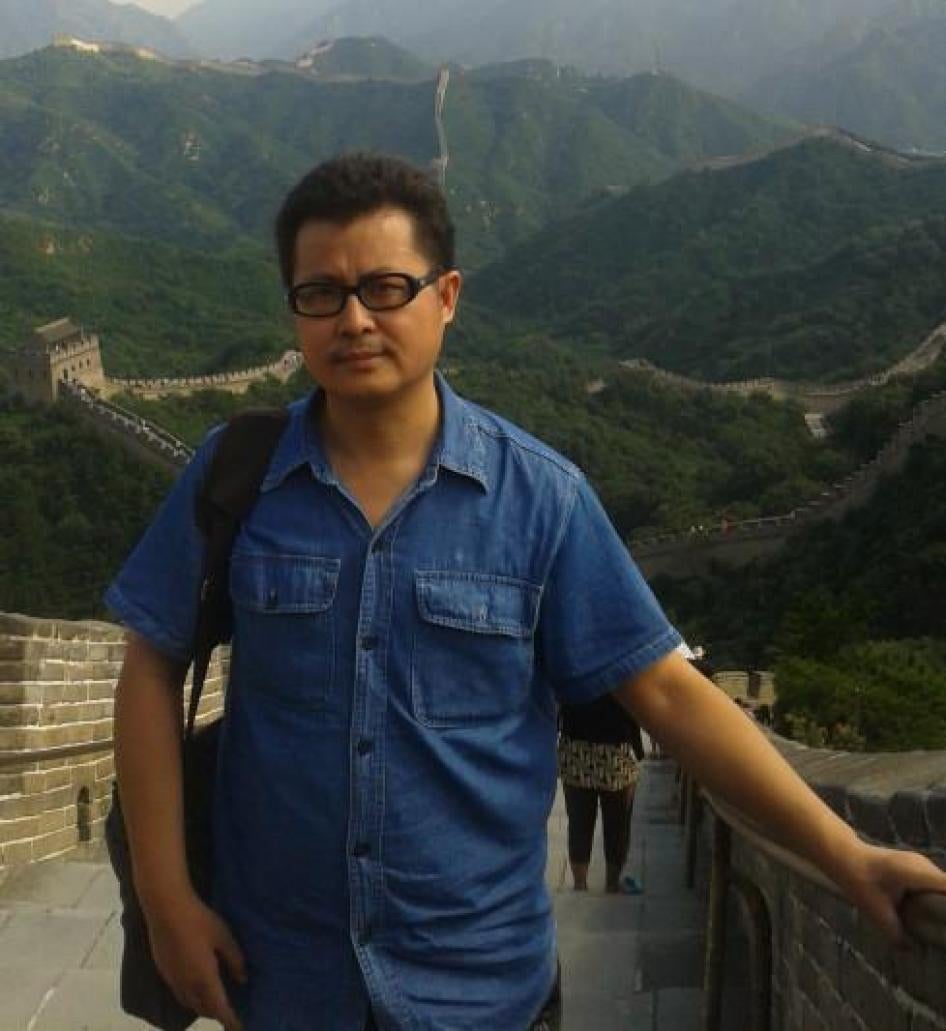

(New York) – Chinese authorities should cease their force feeding of imprisoned activist Guo Feixiong and ensure his immediate access to adequate medical care, Human Rights Watch said today. Guo, 49, a rights activist whose real name is Yang Maodong, has been on hunger strike at Yangchun prison in Guangdong province since May 9, 2016, to protest China’s authoritarian rule and its mistreatment of political prisoners.

“Chinese authorities should immediately end their abusive treatment of Guo Feixiong,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. “Guo’s case highlights China’s poor treatment of detainees, made even worse by denying them access to adequate medical care.”

Family members told Human Rights Watch that prison authorities began in mid-May to force-feed Guo once a day. Since mid-June they have force fed him twice a day every other day. They said that each feeding requires a painful procedure in which authorities force a feeding tube into his nostrils and down his throat into his stomach. A liquid nutritional supplement is then pushed down the tube. Debilitating risks of force-feeding include major infections, pneumonia, collapsed lungs, heart failure, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other psychological trauma.

Force feeding prisoners who are on a voluntary and informed hunger strike – a form of peaceful expression – is contrary to international standards, Human Rights Watch said.

The force feeding process as well as the denial of adequate medical care amount to cruel and inhuman treatment in violation of the Convention Against Torture, which China has ratified. Because of force-feeding’s invasive nature, the World Medical Association, the preeminent international organization in the field of medical ethics and practice, has repeatedly condemned force-feeding of competent prisoners.

Force feeding prisoners who are on a voluntary and informed hunger strike – a form of peaceful expression – is contrary to international standards, Human Rights Watch said.

The force feeding process as well as the denial of adequate medical care amount to cruel and inhuman treatment in violation of the Convention Against Torture, which China has ratified. Because of force-feeding’s invasive nature, the World Medical Association, the preeminent international organization in the field of medical ethics and practice, has repeatedly condemned force-feeding of competent prisoners.

Guo should never have been imprisoned in the first place, and his cruel treatment since sends a chilling message about human rights in China today.

Sophie Richardson

China Director

Guo’s sister last visited him on June 7. Since then her repeated requests to see him have been denied even though Chinese law allows family visits once every month. The last time his lawyer was granted a visit was on June 20. They said that Guo looked very thin and had lost about one-third of his body weight.

The authorities have repeatedly abused Guo in a detention center and prison since he was first taken into custody on August 8, 2013. During his two and a half years of detention in Tianhe Detention Center in Guangzhou City, Guo was not allowed out of his overcrowded cell at any time, contrary to article 25 of the Detention Center Regulations and international standards, which require that detainees be allowed out of their cells to exercise every day.

Over the past year, Guo has suffered intermittent bloody or watery stools, as well as occasional bleeding in the mouth and throat. Although Yangchun Prison twice admitted him to hospitals – once to Yangchun Prison Hospital and another time to Yangjiang City People’s Hospital in Guangdong Province – between April and May, when he was given medical checks, he was not treated or diagnosed. He has also been moved to a crowded cell where the prison guards frequently insult him.

During his hunger strike, Guo has made four demands: that President Xi Jinping should undertake political reforms; the use of electric shock should be abolished in all prisons; the treatment of political prisoners should be improved; and China should ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which it signed in 1988.

Guo is serving a six-year sentence after a court in Guangzhou City found him guilty of “gathering crowds to disturb social order” and “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” in November 2015. He was sentenced for demonstrating in January 2013 outside the office of Southern Weekly, an outspoken newspaper, protesting censorship of an editorial, and organizing others to post online photos of themselves engaged in similar protests in eight other cities.

Guo began his activism in 2005, when he acted as a legal advisor to Beijing lawyer Gao Zhisheng. Guo is best known for his central role defending the rights of villagers in Taishi Village, a landmark case in the “weiquan” (“rights defense”) movement in China. Guo was previously imprisoned from 2006 until 2011, during which he was repeatedly tortured, including with electric shock. Guo is one of China’s most influential rights activists together with lawyers Gao Zhisheng, Chen Guangcheng, Teng Biao, and Xu Zhiyong.

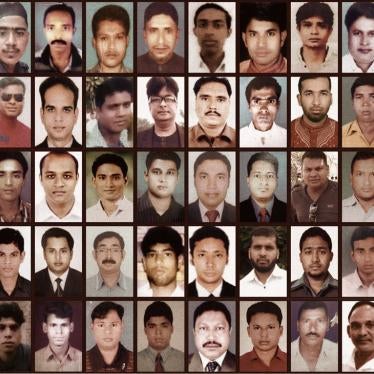

Human Rights Watch called on Chinese authorities to end all torture and ill-treatment of prisoners and detainees, including denial of medical treatment; to accept an independent, international investigation – with the participation of forensic and human rights experts from the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights – into the ill-treatment and deaths of detained activists, including Cao Shunli and Tenzin Delek Rinpoche; and permit a visit by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Foreign diplomats from all countries with bilateral human rights dialogues with China, or those that signed the March 2016 statement criticizing China’s human rights record at the UN Human Rights Council, should request visits to see Guo at Yangchun Prison. If such requests are denied or receive no response, they should go to the prison and personally request access to Guo and to meet with prison officials to express concerns about his case.

“Guo should never have been imprisoned in the first place, and his cruel treatment since sends a chilling message about human rights in China today,” Richardson said. “Respecting Guo’s rights could help begin to repair the damage done.”

The authorities have repeatedly abused Guo in a detention center and prison since he was first taken into custody on August 8, 2013. During his two and a half years of detention in Tianhe Detention Center in Guangzhou City, Guo was not allowed out of his overcrowded cell at any time, contrary to article 25 of the Detention Center Regulations and international standards, which require that detainees be allowed out of their cells to exercise every day.

Over the past year, Guo has suffered intermittent bloody or watery stools, as well as occasional bleeding in the mouth and throat. Although Yangchun Prison twice admitted him to hospitals – once to Yangchun Prison Hospital and another time to Yangjiang City People’s Hospital in Guangdong Province – between April and May, when he was given medical checks, he was not treated or diagnosed. He has also been moved to a crowded cell where the prison guards frequently insult him.

During his hunger strike, Guo has made four demands: that President Xi Jinping should undertake political reforms; the use of electric shock should be abolished in all prisons; the treatment of political prisoners should be improved; and China should ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which it signed in 1988.

Guo is serving a six-year sentence after a court in Guangzhou City found him guilty of “gathering crowds to disturb social order” and “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” in November 2015. He was sentenced for demonstrating in January 2013 outside the office of Southern Weekly, an outspoken newspaper, protesting censorship of an editorial, and organizing others to post online photos of themselves engaged in similar protests in eight other cities.

Guo began his activism in 2005, when he acted as a legal advisor to Beijing lawyer Gao Zhisheng. Guo is best known for his central role defending the rights of villagers in Taishi Village, a landmark case in the “weiquan” (“rights defense”) movement in China. Guo was previously imprisoned from 2006 until 2011, during which he was repeatedly tortured, including with electric shock. Guo is one of China’s most influential rights activists together with lawyers Gao Zhisheng, Chen Guangcheng, Teng Biao, and Xu Zhiyong.

Human Rights Watch called on Chinese authorities to end all torture and ill-treatment of prisoners and detainees, including denial of medical treatment; to accept an independent, international investigation – with the participation of forensic and human rights experts from the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights – into the ill-treatment and deaths of detained activists, including Cao Shunli and Tenzin Delek Rinpoche; and permit a visit by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Foreign diplomats from all countries with bilateral human rights dialogues with China, or those that signed the March 2016 statement criticizing China’s human rights record at the UN Human Rights Council, should request visits to see Guo at Yangchun Prison. If such requests are denied or receive no response, they should go to the prison and personally request access to Guo and to meet with prison officials to express concerns about his case.

“Guo should never have been imprisoned in the first place, and his cruel treatment since sends a chilling message about human rights in China today,” Richardson said. “Respecting Guo’s rights could help begin to repair the damage done.”