The Afghanistan government appears to have a new policy for dealing with government officials accused of sadistic torture: it rewards them with job promotions.

President Hamid Karzai has announced that he will appoint Asadullah Khalid as chief of Afghanistan’s main intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security (NDS). Khalid is no garden variety spy chief. The current minister of border and tribal affairs and former governor of Kandahar and Ghazni provinces, he has been accused of running an unauthorized secret prison in Kandahar where torture was routine. Parliamentary confirmation is by no means a sure thing, but Karzai regularly circumvents parliament’s control over cabinet appointments by leaving government officials in an acting capacity for years.

“This will take the NDS back 10 years, to when they could do anything they wanted while everyone looked the other way, as long as they were killing Talibs,” a diplomat with many years’ experience in Afghanistan told Human Rights Watch. “If the U.S. doesn’t stand up and fight this, it will prove that they have lost all interest in human rights and the rule of law in Afghanistan.”

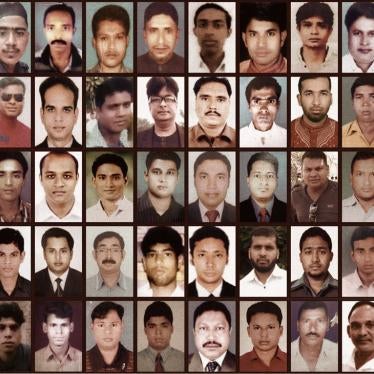

The appointment is especially worrisome since the NDS already has a long and well documented history of torture of detainees. A grisly 2011 United Nations report found that NDS agents routinely used torture to extract confessions or for punishment. Nearly half of all conflict-related NDS detainees interviewed by the United Nations reported they had been tortured in NDS custody. The alleged methods detailed are horrific: beatings with rubber hoses, electric cables, wires, and wooden sticks, often on the soles of the feet; hanging of prisoners by their wrists for long periods; electric shock; twisting of genitals; ripping out toenails; and prolonged standing.

The U.N. report forced NATO troops to temporarily suspend transfers of prisoners to the NDS facilities where the most serious torture was taking place. International law prohibits any country from handing over a prisoner where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being tortured. A U.S. law also prohibits U.S. funding to any unit of a foreign security force that has committed gross violations of human rights, unless effective measures are being taken to bring those responsible to justice.

The Afghan government reacted with fury and confusion to the U.N. report, simultaneously denying use of torture and vowing to end abuses. Since then, it has been hard to detect progress. Commanders at some facilities were moved, but prosecutions and firings of those responsible have been notably absent. “Some were transferred,” a senior international official told Human Rights Watch. “Some were promoted.”

Now, in an apparent attempt to surround himself with cronies, Karzai has also promoted Khalid. American, U.N., and Canadian sources have claimed that forces under Khalid’s command ran a secret prison when he was governor of Kandahar, employing many of the forms of torture detailed above. Khalid has also been accused of corruption, involvement in Afghanistan’s narcotics trade, and of ordering the assassination of U.N. staff members. He has been described by a U.S. official as a “bag man” handing out money for votes as part of Karzai’s 2009 re-election effort.

Khalid has in the past denied all wrongdoing, but many of these allegations were corroborated in a 2008 report by Canada’s Military Police Complaints Commission. Canadian authorities interviewed detainees and documented multiple cases of torture. Canada’s deputy ambassador to Afghanistan testified about serious abuses linked to Khalid.

The appointment of Khalid marks a new low in a long list of rights abusing appointments by President Karzai. Khalid’s appointment occurred just ahead of the September 9 deadline when the Afghan government was to take full control of the U.S. detention center in Bagram, north of Kabul. The facility contains what the U.S. and Afghan governments contend are the highest value insurgents captured on the battlefield. The perceived value of these prisoners as sources of intelligence on the Taliban and other insurgent groups puts them at high risk for torture, and this appointment drops them in Khalid’s hands.

The U.S. and other troop-contributing nations have collaborated closely with the NDS since 2001, sharing intelligence, conducting joint investigations, and cooperating in custody and interrogation of prisoners. The NDS receives significant support, financial and otherwise, from partner countries, primarily the United States, which helped rebuild Afghanistan’s intelligence services after the fall of the Taliban and has had a very close relationship with the NDS since.

Afghan activists are rightly angry and fearful about Khalid’s appointment and what it means for their country before the international troop withdrawal over the next few years. The U.S., other key countries, and the U.N. need to speak out forcefully against Khalid’s appointment and make it clear to Karzai that it is unacceptable to put a known human rights abuser in a position of authority. If his appointment goes unopposed by the U.S. and other countries, that sends a message too, and raises serious questions about whether they really care about human rights in Afghanistan.