(Tokyo) – Japan’s system of “hostage justice” denies criminal suspects the rights to due process and a fair trial, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 101-page report, “Japan’s ‘Hostage Justice’ System,” documents the abusive treatment of criminal suspects in pretrial detention. The authorities strip suspects of their right to remain silent, question them without a lawyer, coerce them to confess through repeated arrests and denial of bail, and detain them for prolonged periods under constant surveillance in police stations. The Japanese government should urgently undertake wide-ranging reforms, including amending the criminal procedure code, to ensure detainees their fair trial rights and make investigators and prosecutors more accountable.

“Japan’s ‘hostage justice’ system denies people arrested their rights to a presumption of innocence, a prompt and fair bail hearing, and access to counsel during questioning,” said Kanae Doi, Japan director at Human Rights Watch. “These abusive practices have resulted in lives and families being torn apart, as well as wrongful convictions.”

Human Rights Watch conducted research in eight prefectures – Tochigi, Chiba, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Aichi, Kyoto, Osaka, and Ehime – between January 2020 and February 2023. Researchers interviewed 30 people either in person or online who were facing or have faced criminal interrogation and prosecution. Human Rights Watch also spoke to lawyers, academics, journalists, prosecutors, and suspects’ family members.

Japan’s Code of Criminal Procedure allows detaining suspects for up to 23 days before indictment by a judge. The authorities interpret the procedure code to allow interrogations throughout this period. Investigators press suspects to answer questions and confess to the alleged crimes even if they invoke the right to remain silent.

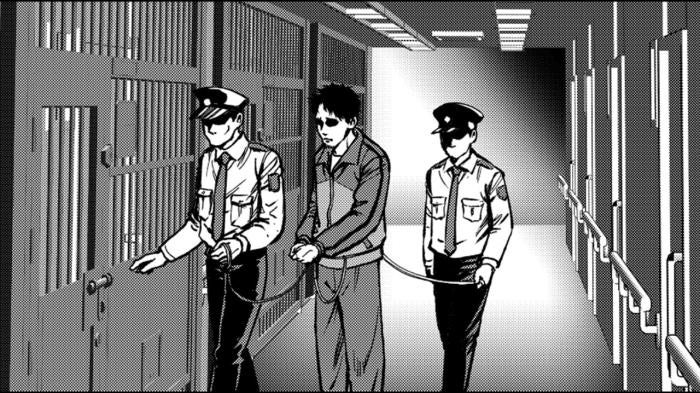

Many suspects are detained in cells in police stations under constant police surveillance, without contact with family members when a contact prohibition order is issued.

Judges routinely allow investigators’ requests for rearrest and prolonged detention. The 23-day detention limit provides no real restriction on pretrial detention, as investigators can use detention for separate, minor crimes or split up charges based on the same set of facts as an excuse to rearrest and detain suspects repeatedly.

Hidemi T. was arrested in September 2018 on suspicion of abusing her 7-month-old son and charged with causing injury. The charge was later dropped due to insufficient evidence. She described to Human Rights Watch how her interrogation continued after she exercised her right to remain silent. “I told the police that I would remain silent immediately after my arrest. The police then became frustrated and continued to interrogate me, still trying to get me to confess that I had assaulted my son.”

Detainees are not allowed to request bail while in preindictment detention. Even when the detainee is indicted and finally allowed to request bail, those who have not confessed or who have remained silent often have a harder time persuading a judge to approve their bail request. Pretrial detention can last for months or even years.

According to Human Rights Watch, judges approved 94.7 percent of prosecutors’ requests for pretrial detention in 2020, and the conviction rate at trial is 99.8 percent.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Japan is a party, states that anyone arrested or detained on a criminal charge must be “promptly” charged before a court. The United Nations Human Rights Committee, the international expert body that provides authoritative analysis of the covenant, has said that 48 hours is ordinarily sufficient time to bring someone before a judge and that any longer delay “must remain absolutely exceptional and be justified under the circumstances.” Furthermore, under the covenant, as a general rule people should not be detained prior to trial.

Human Rights Watch and Innocence Project Japan, a Japanese nongovernmental group, also announced today that they are planning a campaign beginning in June 2023 to end “hostage justice.”

“Japanese authorities should act urgently to reform the criminal justice system to respect everyone’s rights to due process and to a fair trial,” Doi said. “Japan should ensure the right to apply for bail during preindictment detention and reform the bail law to bring it in line with international standards of presumption of innocence and individual liberty.”

Selected Quotes

Yasutaka Sado, was arrested in October 2017 and remained in custody for 14 months before being released on bail. He said:

I attempted to maintain silence but was constantly berated, being told things like “you are maintaining silence because you are guilty” or “don’t you understand how much trouble you are causing to others by maintaining silence?” I was interrogated by the prosecutors three times a day, mornings from 9 a.m. to noon, afternoons from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m., and nights from 7 or 9 p.m. to 10 p.m. This continued for 20 days. The only break was a lawyer meeting or a visit to the hospital.

Kazuya Yoshino, who was prosecuted and tried for “injury causing death,” talked about his being interrogated in 2010:

I told the police my version of events clearly, but they treated the story as if it were a completely different case. Immediately after arrest, the interrogation continued throughout the night – then around 5:30 a.m. they took me to a detention center and the interrogation started again after breakfast. On the second day of my detention, I was taken to see a prosecutor. The prosecutor wanted me to confess that I was in rage and punched the attacker many times to hurt him. I was being interrogated from morning until evening by the police and the prosecutor. As soon as my interrogation with the police ended, I was taken – tied by a rope and in handcuffs – to see the prosecutor. I was made to wait there until around 8 p.m. The actual interrogation by the prosecutor was very brief and I was asked if I “had changed my mind” and would “talk now.” That happened every day – being harassed and forced to confess.

In 2015, Kayo N. was arrested for conspiracy to commit fraud. After her arrest and detention, the judge issued a contact prohibition order on the grounds that she might conspire to destroy evidence. Kayo N. was not allowed to see anyone but her lawyer for one year, could not receive letters, and could only write to her two adult sons with the permission of the presiding judge. She said:

After I was moved to the Tokyo detention center, I was kept in the “bird cage” [solitary confinement] from April 2016 to July 2017. It was so cold that it felt like sleeping in a field, I had frostbite. I spoke only twice during the day to call out my number. It felt like I was losing my voice. The contact prohibition order was removed one year after my arrest. However, I remained in solitary confinement.