A landmark conviction in Germany of a former Syrian intelligence official for crimes against humanity a year ago was a breakthrough in the fight for justice for atrocities in Syria. Regrettably, in November 2021, a French court issued a decision in a case concerning another Syrian national that highlighted some provisions in French law that restrict victims’ access to justice for serious crimes committed abroad.

Human rights groups, including Human Rights Watch, International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), and Amnesty International France have been sounding the alarm about these restrictions for years. At a time when the international community has recognized the imperative of justice in Ukraine and elsewhere, the French government should move ahead with the needed reforms so that survivors can have for their day in court and those responsible for atrocity crimes can be held to account.

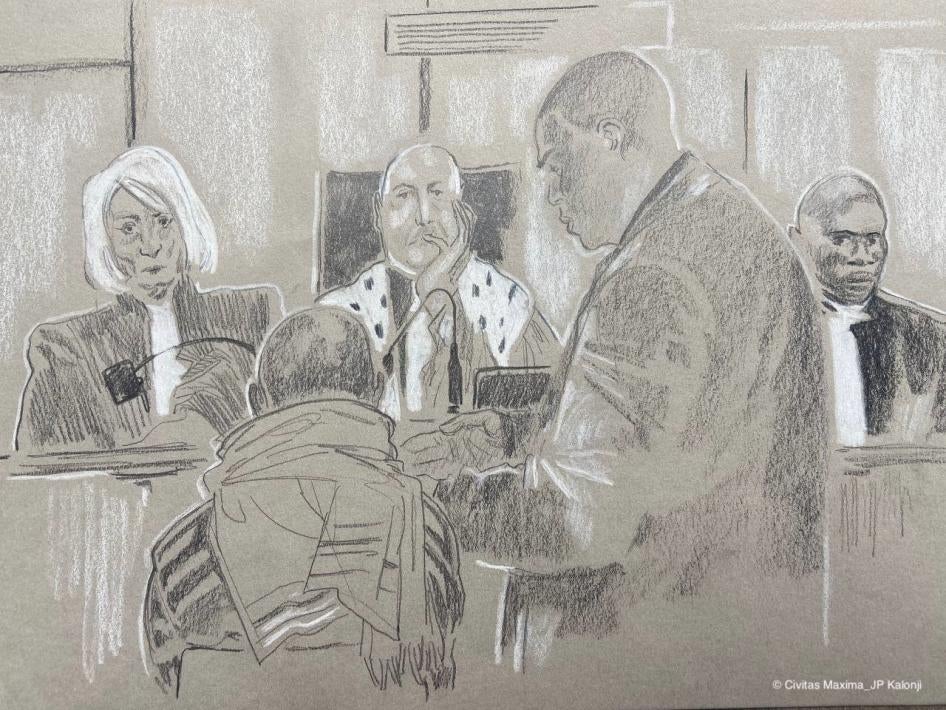

A trial in Paris in November underscores the importance of such cases and the need for France to ensure its courts can offer justice for victims of the worst international crimes. The court sentenced a former Liberian rebel commander, Kunti Kamara, to life in prison for crimes against humanity, torture, and barbaric acts.

Nearly two decades since the conflicts ended, the decision was concrete progress after many unheard calls to set up a war crimes court in Liberia and inaction by successive Liberian governments. We were in the courtroom, and for victims in the room and beyond, the verdict was received as a ray of hope on the long road to justice for the grave abuses during Liberia’s civil wars.

Kamara’s conviction is also a testament to France’s efforts in the fight against impunity. Like some other countries in Europe, France has police and prosecutors dedicated to bringing cases involving serious crimes committed abroad. This is possible because French law recognizes the principle of universal jurisdiction, and allows for investigating and prosecuting international crimes regardless of where they were committed, and regardless of the nationality of the suspects or victims.

However, overly restrictive limitations in the law can allow alleged perpetrators of serious crimes present on French territory to escape justice. In the November 2021 decision, France’s Court of Cassation, the highest court in the French judiciary, annulled the indictment of an alleged former Syrian agent who was accused of complicity in crimes against humanity. In a perverse application of what is called the “dual criminality rule,” the court held that the prosecution could not proceed under French law because there are no provisions in domestic Syrian law that explicitly criminalize crimes against humanity. The court failed to take into account that such acts are, and were at the time, criminalized under international law applicable in Syria.

Following that decision, civil society, lawyers, and survivors expressed concerns that misapplication of the dual criminality rule would result in France becoming a safe haven for people responsible for the world’s worst crimes.

Last April, another case involving a Syrian national highlighted a second problematic limitation in French law: the requirement that an accused person must habitually live on French territory. In that case, the Court of Appeal did take into account that Syria was bound by international law provisions prohibiting war crimes, establishing a less restrictive interpretation of the dual criminality rule at odds with the Court of Cassation’s earlier decision.

Because this case created an inconsistency in French case law, the full Court of Cassation decided to convene to consider the issue. A decision is expected sometime in 2023.

These are not the only conditions French law imposes that might prevent successfully prosecuting cases involving serious crimes. Unlike for other crimes in France, the prosecutor in these cases has discretion in deciding whether to prosecute. Second, French civil society groups have also expressed concerns around a requirement that French prosecutors verify whether any other national or international court has asserted its jurisdiction before opening an investigation. Some of the restrictions are applicable for some crimes, but not others. This has created a discrepancy in how different grave crimes (crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide, torture, forced disappearance) are addressed in the country.

Overall, these restrictions and inconsistencies are out of step with France’s stated commitment to international justice and the fight against impunity. The French judicial officials involved in this work have indicated that the dual criminality rule could affect more than half of their caseload, impeding their ability to move forward with prosecutions.

Before the 2022 presidential election, the French government had expressed its openness to reform its law concerning serious crimes committed elsewhere. Regardless of the Court of Cassation’s upcoming decision, the government should ensure its laws are aligned with its stated commitment to international justice, and follow through on the legislative changes necessary to remove restrictions that frustrate justice in France for serious crimes.

Kunti Kamara’s conviction showed what French justice can help achieve on behalf of victims of the most serious crimes. French authorities should act to amend flaws in the country’s legislation to ensure that survivors of atrocities in other contexts also have equal access to justice.

Benedicte Jeannerod is France director and Alice Autin is an officer for the International Justice Program, both at Human Rights Watch.