The conviction in Germany on January 13 of a former Syrian intelligence official for crimes against humanity marks a major breakthrough in the fight for justice for atrocities in Syria. In sharp contrast, a French court’s decision in November raises fears that France could harbor perpetrators of similar crimes in Syria and elsewhere.

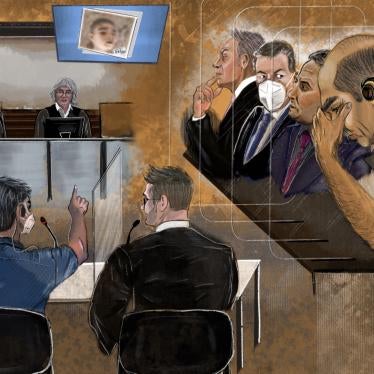

The court in Koblenz, Germany, found the official, Anwar R., guilty of overseeing the torture of thousands of detainees, dozens of murders, as well as rapes and sexual assaults, in a detention center in Damascus, Syria. It sentenced him to life in prison for his crimes.

The Koblenz trial was the first in the world to address large-scale state-sponsored torture in Syria. It was able to do so thanks to Germany’s acceptance of the legal principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows national judicial authorities to prosecute the most serious crimes under international law even if they were not committed within the country’s territory, or by or against one of its citizens.

On January 19, a second trial for crimes against humanity committed in Syria started in Germany, at a court in Frankfurt, under the same legal principle.

Universal jurisdiction is an extremely important tool where other avenues to justice are closed. In the case of Syria, it is the only current recourse for victims of atrocities. Syria is not a member of the International Criminal Court (ICC), and both Russia and China have blocked the UN Security Council from giving the ICC a mandate to investigate serious crimes there.

Syrian survivors and their allies in France may therefore rightly have a bitter-sweet feeling as they welcome the Koblenz verdict and hear of the opening of a second trial in Germany. In the November decision, France’s Court of Cassation, the highest court in the French judiciary, annulled the indictment of an alleged former Syrian agent who had sought asylum in France and who was accused of complicity in crimes against humanity. In a perverse application of the “dual criminality rule,” France’s highest court held that the prosecution could not proceed under French law because Syrian law does not explicitly criminalize crimes against humanity.

The “dual criminality rule” refers to the legal norm that the act for which a person is being prosecuted or extradited is a crime in both the host country and where the act took place. The rule prevents arbitrary prosecutions for behavior that was legal in the country where and when it was committed. It is a due process guarantee that reflects the requirements of legal certainty and foreseeability. However, it is not intended to shield behavior that is criminal under international law.

In asking whether the dual criminality rule has been satisfied when prosecuting an individual accused of crimes against humanity in Syria, for example, a court should not only consider Syria’s domestic law, but also ask if the offending behavior would constitute a crime against humanity under international law at the time when it was committed. If the answer is yes, due process is protected. The European Court of Human Rights confirmed this approach. The French court’s November ruling shifts the burden to France to bring its law in line with these human rights norms.

This is not the only restrictive condition French law imposes on applying universal jurisdiction. For example, France’s law also requires that the defendant be officially resident in France for a prosecution of serious crimes to proceed. Human rights groups have long urged successive French governments to amend these flaws in the relevant legislation, but no action has yet been taken. The Court of Cassation’s recent decision underlines the urgency for the government and the parliament to address these legal restrictions so that France does not become a safe haven for people responsible for the world’s worst crimes.

With other avenues for justice currently blocked, criminal investigations in Europe offer a beacon of hope for victims of crimes in Syria and elsewhere who have nowhere else to turn. French authorities should ensure that their laws do not deprive survivors of the chance for their day in court.