In 2008, when China first hosted the Olympics, the event was often described as a “coming out party” for the country. It was an awkward fit for a country nearing 60 which had been “opening up” for the past three decades. Besides, Beijing was hosting the party, not just getting dressed up to attend it.

And yet, as preparations for the Games ramped up, the metaphor didn’t feel wholly inapt. Across the capital, service-workers practiced their English and took lessons on etiquette, neighborhood committees donned fresh-pressed athletic garb and lines appeared down the middle of escalator stairs to encourage orderly ascent. Certain aspects of the national toilette—silencing government critics, removing migrant workers from the streets, spray-painting dead grass green—may have bespoken discomfort with outside scrutiny, yet the country seemed largely unified in readying itself for a grand entrance. “Beijing Welcomes You,” the Games’ cheerful mascots intoned. They might as well have been saying, “Please Welcome Us.”

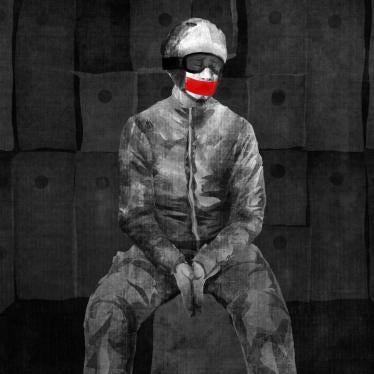

Neither motto seems suitable for 2022. In February Beijing will host the Games again, this time amid a surging pandemic, a new wave of lockdowns, at least 10 diplomatic boycotts, and international alarm at the disappearance of one of the country’s top athletes. “Together for a Shared Future,” read the words beneath the interlocking rings this year. But what will be shared and how and with whom seems infinitely more vexed a question than at any time since the Olympic torch last blazed down the Avenue of Eternal Peace.

We asked contributors to comment on what the Beijing Games mean this year and to what extent they mark a significant juncture in China’s relations with the world. —Susan Jakes, ChinaFile Editor

Comments by Maya Wang

In some ways, the 2008 and 2022 Olympic Games could not be more different. The 2008 Games were Beijing’s “coming out party,” while the 2022 Games face diplomatic boycotts. The 2008 torch relay went through major Western capitals, but a similar relay would be unimaginable today given growing international discomfort with Beijing’s propaganda exercises as well as COVID-19.

And yet, the Chinese government has been deeply authoritarian all along. The year 2008 was marked by the Chinese authorities’ repression of Tibetans and of those seeking accountability for schoolchildren who died in the Sichuan earthquake, and by Beijing’s failure to live up to human rights commitments made to get the Games. Instead of holding Beijing accountable, other governments and the International Olympics Committee (IOC) looked the other way.

Now, as Beijing’s abuses deepen and as Xi Jinping seeks to assert the Chinese government’s power and influence beyond the country’s borders, some governments have demonstrated that they recognize the Chinese Communist Party as an ambitious force aspiring to remake the world in a manner more friendly to itself—and less friendly to human rights and democracy.

At least 10 governments have declined to send diplomats to the 2022 Beijing Olympics specifically in response to Beijing’s human rights violations, while five others said they made the decision due to COVID concerns.

More striking is the range of governments and officials who will show up for Beijing’s party even as the authorities commit crimes against humanity in Xinjiang and crush freedoms in Hong Kong. The 2022 Olympics opening ceremony will include the usual suspects, such as Russian President Vladimir Putin, who says he will attend in a display of unity. But it will also feature senior diplomats from democratic governments, such as Norway, which seems to be prioritizing major business interests over human rights.

Official attendees will most likely also feature Muslim-majority governments that have cooperated with Beijing on its global hunt for Xinjiang’s Uyghurs, persecuted precisely because of their faith. Finally, United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres—whose tenure has been marked by a lackluster performance on human rights—will attend to promote “peace in the world.”

But the gold medal for spectacular complicity in human rights abuses should go to the IOC. After the tennis star Peng Shuai accused a retired top Chinese government official of sexual abuse, the IOC participated in the Chinese government-directed drama of covering up these abuses. When the respected digital rights organization Citizen Lab revealed “devastating” privacy vulnerabilities in an app for Olympic attendees, the IOC dismissed them. Whatever allegations there are against the Chinese government, the IOC seems determined to pretend that everything is on track as long as the Games keep the dollars pouring in.

Instead of a celebration of the human spirit, the 2022 Beijing Games seem destined to go down in history as a display of an endless capacity from some governments and institutions for abuses and hypocrisy.