UN Women, UNICEF and Human Rights Watch jointly issue this fifteenth alert to continue to highlight the gender specific impact of COVID-19 in Afghanistan. This alert focuses on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and girls’ education and the long-lasting consequences it will have on gender equality, women’s human rights and Afghanistan’s development and peace efforts. It highlights how the health crisis has further reduced already severely limited access to education for women and girls, and how this is likely to have profound and lasting effects with the potential to undermine progress on women’s rights and gender equality achieved over the last two decades.

This alert concludes with a set of recommendations for consideration by national and international stakeholders. UN Women, UNICEF, and Human Rights Watch are committed to advancing the rights of women and girls, including through the COVID-19 crisis. This alert serves to advance this aim by providing a basis for an informed discussion on the gender-specific impacts of COVID-19 on women and girls’ education. It highlights how critical it is, as part of COVID-19 response and recovery efforts, to prioritize and invest in ensuring girls’ continuous access to safe, inclusive and quality education and second chance education for women who were denied earlier access to a safe and quality education. Such commitments and investments are essential to ensure that progress made towards achieving gender equality in Afghanistan will be continued, and that Afghan women and girls will have equal access to education, as is their right under international human rights law including the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

Context & pre-existing barriers to education for girls and women

Education is a right for all children and an educated population is essential for building a self-reliant, peaceful, equal, and inclusive Afghan society. Afghanistan’s education system has been severely impacted by decades of conflict, widespread poverty and humanitarian crisis. Today, funding remains insufficient, as only 3% of Afghanistan’s Gross Domestic Product is allocated to education. International standards state that the government should spend at least 4 to 6% of GDP on education.[1] The Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4 recognizes that to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, least developed countries need to dedicate at least or more than 4 to 6%.[2] Afghanistan budgets far less than this, and even with this small percentage of funding the country’s education budget continues to be underspent every year.[3]

Afghanistan has one of the youngest populations in the world, with almost half of the population (48 %) – under the age of 15, and 68% under 25 years of age.[4] Women and girls’ education, has immense social and economic benefits for the development of countries. Education is a determinant of women’s engagement in the development of the country, public and social life. Afghanistan’s National Education Strategic Plan (2017 – 2021) acknowledges that investments in girls’ education to improve access and efficiency are necessary to ensure equality in access to education. Access to quality education is particularly critical in Afghanistan, where young people, especially girls, need education to prepare them as they try to break the country’s cycles of gender inequality, crisis, poverty and conflict, and move Afghanistan toward gender equality, peace and development.

Since 2001, the number of children in school has risen by almost nine times from 0.9 million (almost none of them girls) to 9.2 million (39% of them girls).[5] The number of schools has also increased from 3,400 to 16,400.[6] At the same time, however, 3.7 million children in Afghanistan, or nearly half of all school-age children, are not in formal education. Approximately 60% of out-of-school children are girls.[7] In January 2016, UNICEF estimated that 40% of all school-age children in Afghanistan did not attend school.[8] For children with disabilities, the numbers are much higher, with an estimated 80% of girls with disabilities not enrolled in schools. This is despite children with disabilities having a right to access inclusive education and on an equal basis with others in their communities.[9]

UNICEF in 2016 estimated that 66% of Afghan girls of lower secondary school age—12 to 15 years old—were out of school.[10] In the poorest and more remote areas of the country, enrolment levels vary widely, and are as low as 14%,[11] and girls still lack equal access to education in virtually every part of the country. Consequently, literacy rates remain low, particularly for young women; only 37% of adolescent girls are literate compared to 66% of adolescent boys.[12] The gender gap in education grows bigger for secondary and university education, with only 4.9% of women accessing tertiary education, compared to 14.2% of men.[13]

Obstacles to education - especially for girls and women - are numerous, particularly in rural areas and areas where anti-government elements have control or influence. According to the 2019 Afghanistan Hard to Reach Assessment,[14] access to education, especially for girls, was found to be relatively low in the assessed Hard to Reach (HTR) districts, with an average of 36% of school-age children reportedly attending school. Of those, 79% were boys and 21% girls. It also noted that education facilities seemed to be more often affected in HTR areas, with schools reportedly closed due to conflict in 26% of target areas. The three main barriers cited for not attending schools were: distance to school (28% for girls compared to 3% for boys); fear of threats and intimidation at school, (29% for girls compared to 14% for boys); and security concerns when travelling (20% for boys and 15% for girls).

Deliberate attacks on education—including against schools, teachers and students disproportionately affect girls, both because girls’ education is often the target of such attacks, and because parents in Afghanistan concerned about their children’s safety often pull girls out of school before boys. The Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA), in its 2017-2019 review, reported that attacks on education accelerated during this period.[15] GCPEA collected reports of more than 300 attacks on schools in this period, which injured or killed at least 410 students, teachers, or education workers.[16] The UN verified 192 attacks on schools and staff in 2018, tripling from 68 such attacks in 2017; 123 of these attacks were attributed to the Taliban and another 42 to the Islamic State.[17] Threats and attacks against students and education personnel also increased, particularly in areas of the country controlled by anti-government elements.[18] In many cases, attacks on education have targeted girls’ schools, as well as female students and educators, demonstrating continued resistance to girls’ education, and leading to the closure of more than 1,000 schools and denying half a million children of their right to education.[19] In 2019, around 722 schools were closed due to insecurity, affecting the education of around 328,094 children.[20] These attacks have continued during the COVID-19 pandemic: in its latest report to the United Nations Security Council, the United Nations Assistance Mission (UNAMA) reported nine incidents of attacks against schools between 1 April and 30 June 2020.[21] In addition, although corporal punishment is legally banned in schools, many teachers, especially in remote areas, continue to use it against students as a disciplinary tool, which has negative impacts on their learning ability and discourages regular attendance in school.[22]

School in Afghanistan is not free, even though government primary and secondary schools do not charge fees. Families of students at government schools are expected to provide supplies, which can include pens, pencils, notebooks, uniforms, and school bags. Many children also have to pay for at least some government textbooks. The government is responsible for supplying textbooks, but often books do not arrive on time, or there are shortages, perhaps in some cases due to theft or corruption. In these cases, children need to buy the books from a bookstore to keep up with their studies.[23] These indirect costs are enough to keep many children from poor families out of school, especially girls, as families that can afford to send only some of their children often give preference to boys.[24]

Poverty drives many children into paid or informal labor before they are even old enough to go to school. At least a quarter of Afghan children between ages 5 and 14 work for a living or help their families, including 27% of 5 to 11-year-olds.[25] Girls are most likely to work in carpet weaving or tailoring, but a significant number also engage in street work such as begging or selling small items on the street. Many more do housework in their family’s home. Many children, including girls, are employed in jobs that can result in illness, injury, an acquired disability or even death due to hazardous working conditions and poor enforcement of safety and health standards. Children in Afghanistan generally work long hours for little—or sometimes no—pay. Work forces children to combine the burdens of a job with education or forces them out of school altogether. Only half of Afghanistan’s child laborers attend school.[26]

In addition, poor, absent, and inaccessible infrastructure continue to be a pressing issue. Nearly half of all schools do not have a building or facilities.[27] In the absence of accessible infrastructure such as ramps or wheelchair-accessible toilets, girls with disabilities are sometimes unable to enter or attend school. According to the Ministry of Education, as of 2016, 40% of schools also lacked boundary walls, a gap that often plays a key role in girls’ families refusing to send them to school, due to concerns about gender segregation, modesty and security for girls.[28] Many schools also lack running water and toilets. Girls who have commenced menstruation are particularly affected by poor toilet facilities. Without private gender-segregated toilets with running water, they face difficulties managing menstrual hygiene at school and are likely to stay home during menstruation, leading to gaps in their attendance that undermine academic achievement, and increase the risk of them dropping out of school entirely.

Lack of female teachers is another barrier to girls’ education, as many parents are only comfortable having their daughters taught by women. Only 33% of teachers are women, with the percentage of female teacher varying widely from province to province, ranging from only 1.8% in some provinces up to 74% others.[29] In addition, only 16% of Afghanistan’s schools are girls-only, and many lack proper sanitation facilities, further hindering attendance.[30] Universities also continue to lack safe transportation and facilities for women students, including water and sanitation facilities and safe university housing.

Children with disabilities often lack access to reasonable accommodation or specific assistance. Because there is no system to identify, assess, and meet the particular needs of children with disabilities, they can be excluded from the education system. A lack of teacher training in inclusive education methods is an additional barrier.[31] For girls and women with disabilities, the long distance from homes to schools, the absence of dedicated, accessible transportation, and the lack of assistants or a family member to accompany the child with limited mobility to school is a significant barrier.[32]

Socio-cultural norms and gender expectations too often do not value girls’ education. Child marriage is both a cause and a consequence of girls being driven out of education; 28% of women marry before the age of 18 and 4% before the age of 15.[33] Afghan law on the age of marriage violates international human rights law by permitting marriage as early as age 15, and setting an earlier minimum age of marriage for girls than for boys.[34] According to the Civil Code, the minimum age of marriage for boys is 18 and for girls it is 16 years old (article 70). If a girl is 15 years old, her marriage is permitted with permission of her father or from a court. Marriage of girls under 15 years old is not allowed under any circumstances (article 71). However, there is an evolving consensus in international law that 18—without exceptions- should be the minimum age for marriage. The committees that interpret the Convention on the Rights of the Child and Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women have each recommended that 18 be the minimum age for marriage for boys and girls, regardless of parental consent.[35] A 2017 national action plan to end child marriage has gone largely unimplemented.[36]

The U.N. Secretary-General called for a global humanitarian ceasefire to combat COVID-19, including in Afghanistan.[37] However, despite this, and the spread of COVID-19, the conflict continues and has escalated in some parts of the country. From 1 January 2020 to 26 August 2020, 151,196 people fled their homes due to the conflict.[38] With limited humanitarian access to these newly displaced people, it has been challenging for humanitarian actors to identify their needs and priorities.[39] However, a study done by the Norwegian Refugee Council before the crisis confirms that internally displaced people (IDPs) had considerably less access to education compared to other urban populations.[40] Restoring education is a pressing need for IDPs.

For internally displaced women and girls, access to education is particularly challenging. Specialized measures to ensure access to inclusive education for IDP children, particularly girls, are critical. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, evidence showed that displaced women and girls faced significant barriers to accessing education even beyond those that other Afghan girls face. IDP children, especially girls, are at particular risk of falling behind inschool due to disruptions in their education and barriers to accessing education in their new locations, including stigma, restrictions on the age at which children can enroll or a requirement that older children go into advanced grades even if they have not previously studied, and requirements for identification and transfer letters that may not be available to them.[41]

Before the pandemic hit, the number of girls attending school was already falling in many provinces. An analysis by Human Rights Watch comparing Afghan government data for 2016-17 to that for 2015-2016 found that in that period in 32 of the country’s 34 provinces the number of girls in primary school decreased, with 206,000 fewer than the previous year, out of a total of about 2.4 million girls.[42] The number of boys fell too, but significantly less – by 124,000 across 23 provinces.[43] A similar review of the 2018-19 data compared to the 2017-2018 data found that the number of girls declined during that period in 13 provinces, while the number of boys declined in 12 provinces.[44] The COVID-19 crisis could accelerate such setbacks to girls’ education.

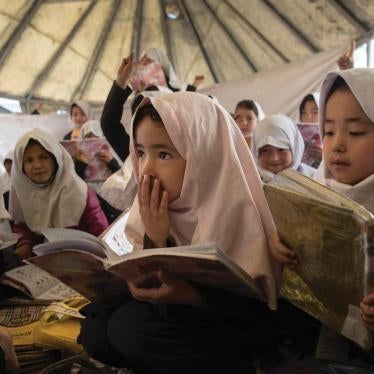

One of the major donor initiatives to try to get more children, especially girls, into school was the creation of community-based education programs (CBEs), which are funded through and operated by NGOs, with the expectation that the government provides oversight. These programs—often referred to as “classes” rather than schools, as they are often based in homes—frequently consist of a single class of 25 or 30 students. They are designed to provide access to education in communities where there is no school nearby. They are also intended to assist children who are behind in their studies, by accepting children who are too old to be admitted to government schools. Many CBEs offer an accelerated program of study, condensing two years’ worth of material into a single year, with the goal of helping children catch up so that they can go to a government school after completing a CBE.[45]

Impact of Covid-19-related school closures on women and girls

On 14 March 2020, as a measure to curb the spread of COVID-19, all schools and educational institutions in Afghanistan were closed. More than 9.5 million children in public schools and 500,000 children enrolled in community-based education classes, in addition to the 3.7 million out-of-school children in Afghanistan, have now been out of school for nearly seven months. On 22 August 2020, government schools across the country reopened for grades 12-7. Private schools were permitted to re-open for grades 12-1. The fact that private school students already have greater access to education than students in government schools is just one indication of the deepening inequalities that are likely to be a widespread consequence of the pandemic.

School closures and disruption of education due to the COVID-19 health crisis have already harmed many children in Afghanistan by further weakening their already tenuous access to education. The pandemic coincides with an often worsening and unpredictable security situation and ongoing armed conflict, and concerns that already declining donor funding could fall further in the wake of COVID-19. The health crisis is compounding existing vulnerabilities and inequalities, further limiting access to education for children who were already marginalized.

Children who were not studying will be less likely to be able to do so, and many children whose schools closed will be a risk of not being able to return to studying. The crisis is likely diverting critical and already scarce resources away from the education system in ways that will have long-term consequences and will set back progress toward making education universally accessible and compulsory for all children. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to education poses one of the biggest threats not only to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 of quality education for all globally by 2030, but also the realization of all other human rights and all 17 SDGs in Afghanistan.

These harms will disproportionately affect girls, especially girls who are marginalized in other ways, including due to disability, because they are IDPs or returnees, or because they are among the three- quarters of the population living in rural areas.[46] It is critical to continue to invest in education and to ensure access to inclusive education for all children, which will support development and peace efforts in the short and long term. COVID-19 will have long-lasting effects on the realization of women’s right to equal opportunities to thrive in public life in Afghanistan, and on gender equality, development and peace in the country as a whole. It is critical to halt declines in the number of girls studying and prevent the COVID-19 crisis from driving new declines in women and girls’ participation in primary, secondary and tertiary education.

When schools and CBE reopen, the fragile education system in Afghanistan will have to grapple with three additional challenges: reenrolment of children, particularly girls, into the schools; remediation for lost learning time; and the likely resurgence of COVID-19 during the cold season. The situation in cold climate provinces where schools are normally closed from end of November until end of March will pose its own challenges

Impact on the most marginalized women and girls

COVID-19 most harms children and families with weaker resilience to crisis and shocks. The

disruption to education is likely to have the biggest impact on the most marginalized and at-risk children, as the crisis exacerbates pre-existing education disparities and reduces their opportunities to continue their education.

Among those most affected are likely to be women and girls from families living in poverty, those living in remote, rural and/or conflict-affected areas, internally displaced and returnee women and girls, and women and girls with disabilities. Many of these women and girls have limited opportunities to continue learning at home, so the closure of schools is likely to particularly affect their longer-term healthy development. Prior to COVID,19-

65% of displaced girls living in hard to reach areas were not enrolled in schools. 36% of households in the hard to reach districted assessed reported loss or diminished access to education. Of the displaced children living in hard to reach areas attending school, only 6% have followed their school curriculum remotely since school closure.[47] Girls with disabilities, who already had limited access to education before the outbreak,[48] have often been neglected and at times excluded from distance learning, and risk also being forgotten in re-opening and mitigation plans.

Families already living in poverty, many of whom are IDPs or returnees, have little ability to weather a new crisis. They will be most under pressure to relieve financial crises through child labor or child marriage. Girls and women lacking adequate access to nutrition and healthcare will face the greatest harm due to losing access to essential support services offered at schools, such as nutrition and psychosocial programmes. The pandemic will continue to feed vicious circles of poverty, further increasing inequalities, eroding social and economic resilience and hampering development and peace at the local and national level.

With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, hundreds of thousands of Afghan families returned to Afghanistan from neighboring countries, creating even greater pressure on the struggling school system.[49] These families are likely to face particularly challenging barriers to education, especially if they are returning to rural and remote parts of the country affected by ongoing armed conflict and lack of access to basic services.

The increased burden of care and effect on girls’ schooling

Prior to the pandemic, a time-use survey conducted by UN Women confirmed that women are providing the majority of unpaid care and domestic labor in Afghanistan. Women spent an average of 4.6 hours on childcare compared to 2.3 hours for men; 3.4 hours caring for others compared to 1.3 hours for men; 3.6 hours preparing food compared to 0.4 hours for men; and 7.3 hours on cleaning compared to 1.6 hours for men. In total, women spend an average of 18.7 hours a day on unpaid care and domestic labor compared to 5.6 for men.[50]

As outlined in the Gender Alert 4 on the Impact of COVID-19 on Women’s Burden of Care and Unpaid Domestic Labor,[51] lockdown and social distancing have significantly exacerbated the already high and disproportionate burden of unpaid care and domestic labor responsibilities women and girls experience in Afghanistan. Forthcoming research by UN Women found that 83% of women saw an increase in unpaid care work and 80% in unpaid domestic work, compared to 75% and 62% for men respectively.[52] Female single parents, including unmarried, widowed and divorced women, felt the burden the most, adding to the other household chores and care work.[53]

Girls are often expected to help shoulder the burden of care and domestic labor in their homes, and as this burden has increased during the pandemic—and school closures have made girls more available to perform this work—it is affecting their future. The increased burden of care is hampering female students’ learning time, resulting in increased learning loss, and affecting their return to schools.

Increased risks of violence against women and girls, exploitation and child marriage

In addition to dropping out of school, education disruption puts girls and young women at increased risk of numerous abuses: child marriage, exploitation, child labor, early pregnancy, and gender-based violence. School closures, the loss of protective spaces provided by school, lockdowns spent at home and COVID-19 mitigation measures disrupt children›s routine, and place new stressors on parents and caregivers, contributing to an increase in the severity and frequency of domestic violence across the country.[54] School closures represent the loss of a safe space, where girls who are experiencing violence and abuse can find respite, and where there is an opportunity for adults to identify signs of abuse and intervene in their lives.[55]

School closures and the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 have increased the risk of reliance on negative coping mechanisms, such as child marriage. With many families losing their means of livelihood, girls are at increased risk of being forced to drop out permanently from school and marry early. An increase in reported cases of child marriage within the first few weeks/months of the pandemic has been documented.[56] Out of school, children are also easy targets of abuse, exploitation and recruitment by armed forces and groups, fueling vicious cycles of conflicts and hindering development.

Schools can provide a safe space where children can be protected from violence and crises. When schools reopen, they need to address public health and safety issues comprehensively, to prevent and respond to COVID-19 but also to ensure the safety of students in and around schools. Safety measures should include measures to prevent COVID-19, such as facilitating and requiring handwashing, social distancing, and measures to protect teachers and staff, but also help to address other safety issues such how students can travel safely to school, safety from gender-based violence in and around schools, and the lack of health services and social protection for girls.

School closures’ impact on girls’ health and safety

In addition to learning loss, school closures are also affecting girls’ health and safety through loss of access to essential services and social protection mechanisms. Some students benefit from health and nutrition programmes through their schools. Loss of access to these programs has a direct impact on increasing hunger and nutritional deficiencies, in communities also struggling with the socio-economic impact of the pandemic. The closure of schools is depriving school-age girls of access to weekly iron and folic acid supplementation provided in some schools, further jeopardizing their health, and potentially increasing already high rates of anemia. Schools serve as a key entry point for providing health and psychosocial services, and that access has been cut off by school closures.

Increased risks of drop out for women and girls

The total number of children not returning to their education after the school closures is likely to be significant. The pandemic also risks jeopardizing some of the gains made since 2001 in re-building women and girls’ education following the Taliban regime. The COVID-19 pandemic is creating additional barriers due to risks—and students’ and parents’ anxiety about risks—associated with children returning to classrooms that are cramped, with no capacity for distancing, often cold, damp and poorly ventilated during the country’s severe winters, and have no or poor hygiene and clean water facilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to drive many women and girls out of education permanently. School closures due to COVID-19, resulting increases in caregiving responsibilities for women and girls, and increases in poverty and unemployment will all make it harder for women and girls to study. These factors combine in harmful ways with pre-existing discriminatory gender norms, ongoing insecurity, and abuses such as child marriage. The likely result is that many more girls will not access education or drop out before completing their education.

Loss of income will likely affect parents’ ability to afford to pay for women and girls’ education. Families that cannot afford educational costs for all their children may prioritize continuing their sons’ education over their daughters, because of discriminatory attitudes, and practical considerations such as the expectation that sons remain living with parents and supporting them financially while daughters are expected to marry and devote their labor and assets to their husband’s family. Prolonged absence from school, weak study habits due to poor quality prior education in over-crowded and under-resourced schools, restrictions on girls’ freedom of movement especially as they get older,[57] and lack of access to books, materials and internet access that could facilitate self-study are all likely to contribute to students, especially girls and women, not returning to education. In some of the provinces which prior to the pandemic had the lowest proportion of enrollment by girls, such as Helmand, Kandahar, Paktika, Uruzgan, and Wardak provinces, girls may be particularly at risk of not returning to school.

Lack of distance learning and interruptions to learning

The protracted closures of schools, and the lack of adequate distance learning measures, severely impacted children’s learning, particularly impacting Afghanistan’s most marginalized children. Lack of available, accessible education materials and restricted access to internet--with only 14% of Afghans using the internet[58] --has restricted opportunities for distance learning. With low rates of literacy, many parents were not able to provide academic support to their children to continue studying at home. An assessment conducted in Herat, Badghis and Ghor found that 53% of households did not practice home schooling for their children and 30.8% of caregivers said they were not able to provide any type of support in terms of homeschooling and education to their children.[59] 76% of the respondents reported that they needed learning and school materials.

Girls are less likely to be able to study remotely, including because they are much more likely than boys to be assigned housework and caring for younger siblings. There is also sometimes resistance to girls and women using technological devices and the internet, and they may even face violence if they do, due to the idea that these devices may expose them to contact with men and boys.[60] These factors make girls more likely to fall behind on their studies when studying remotely, which will both compromise their future academic achievement and make it more likely that they will not return to school. Remedial education for girls—and other children who need it--should be offered to recover education time lost during the closures.

Lack of washing and sanitation facilities hindering COVID-19 prevention

Lack of water and accessible sanitation facilities already was a major factor preventing many girls and young women from continuing their education, but now it is also a key issue undermining efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In 2017, only 60% of government schools had toilet facilities.[61] Currently, many schools are unable to meet the minimum requirements to keep children safe due to the lack of washing and sanitation facilities, including lack of running water.[62] 30% of Afghans lacked safe drinking water, and some had no running water at all.[63] This is a major barrier to the practice of good hygiene, instrumental in effectively preventing COVID-19.

Fear of contracting and spreading COVID-19 in schools, including due to the lack of washing facilities may also deter children from returning to schools, particularly girls and young women. Enhancing hygiene will be critical to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and will also provide an opportunity to address the long-standing lack of adequate sanitation facilities for women and girls within school infrastructure.

Risk of reduced funding to education due to the economic impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic poses serious systemic risks to Afghanistan’s education system, and to attention to girls’ education by donors. The economic consequences of the health crisis are being sharply felt around the world, including in some of the countries that are the largest contributors to international development assistance. Afghanistan is deeply dependent on donor assistance, including to fund its education system, and initiatives to support girls’ education and gender equity within the education system have usually been funded, and often driven, by donors. As development assistance comes under strain, this could jeopardize the already inadequate funding for education, further exacerbating the major challenges the Afghan education system was already facing—and cutting off funds and focus that have been crucial to the progress that has been achieved in advancing girls’ education. Globally, it is estimated that the COVID-19 crisis will increase the education financing gap by up to one-third.[64]

RECOMMENDATIONS:

All COVID-19 response and recovery plans should take into accountand tackle gender-specific barriers to women and girls’ access to education. As the government works to restart schools, there is an opportunity to enhance gender equity in access to and availability of education. This can be realized by: (1) ensuring that gender equity is included as a core component of all strategies responding to COVID2) ;19-) ensuring that increasing gender equity is a key consideration in planning, funding and delivering infrastructure development, and ensuring that priority is given to developing basic infrastructure such as toilets, running water, boundary walls, and accessible buildings that will help girls and women be able to study; (3) ensuring that curriculum and teachers integrate gender equality and women’s rights as an educational priority; and (4) ensuring recruitment of more women teachers, in line with previous efforts of the Government including a plan to recruit 30,000 female teachers.[65] In line with the 2020 recommendations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women concluding observations on the third periodic report of Afghanistan, the government should:[66]

- Ensure that at the national level, pandemic preparedness and response plans prioritize safe access to inclusive education and address the gender-specific barriers and needs related to women and girls’ access to education, including the most marginalized women and girls.

- Reform legislation to remove all provisions that discriminate on the basis of gender, including setting the minimum age of marriage at 18 for women and men.

- Draft new legislation to improve gender equality, including ensuring equal access to education for girls and boys, and access to services for survivors of gender-based violence

- Advocate and support the inclusion of gender equality and women’s rights in the national curriculum.

- Engage entire communities in safe school re- opening, and women and girls’ return to school, by communicating about COVID-19 mitigation measures and the value of women and girls’ education, and following up with individual girls and women who do not return to school or educational programs.

- Provide information, training and materials to ensure effective COVID-19 mitigation measures, including through provision of child-friendly information and supplies. Including:

- Ensure that schools and community-based classes implement a minimum package of safety measures including masks, hygiene kits to all children, access to clean water (through distribution of water storage and chlorination where applicable and possible), hand sanitizers, and anti-bacterial soap.

- Ensure that schools and CBE have clear protocols/ instructions when a student or teacher displays symptoms of COVID-19 (temporary quarantine on site, recording of cases, referral to health actors, etc.) without creating discrimination/ stigma for the individual.

- Consider using and expanding the CBE model both to safely re-open schools and to use their expertise to help girls catch up, including for girls who go to government schools.

- Ensure that education programmes take into consideration the gender differentiated needs of women and girls, including for most marginalized women and girls.

- Ensure access to safe and accessible infrastructure, sex-segregated sanitation facilities, and safe and adequate washing facilities including access to clean water, hygiene kits and disinfectant in all schools.

- Establish and implement prevention and response programmes to address all forms of violence against women and girls and violence against children, including violence in and around schools, on the way to school, and in students’ homes.

- Support women and girls’ education through incentives such as grants and scholarships.

- Support female teachers’ recruitment and retention, including by improving their salaries and career progression and ensuring their safety and protection from violence and sexual harassment.

- Strengthen measures to include all children with disabilities in education, and ensure that all COVID-19 related measures, including remote learning and school re-opening, takes into account the need to provide reasonable accommodations and guarantee accessibility to ensure full access to inclusive education for all children with disabilities.

- Develop measures to guarantee continued access to education for conflict-affected, displaced and returnee populations.

Support children in alternative care and children in detentions to have access to education, safe release and reintegration in communities and families.

______________

[1] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) et al. (2015). Education 2030: Framework for Action. art. 105.

[2] bid.

[3] ACT Alliance (2020). Afghanistan: More challenges for women and girls due to COVID-19.

[4] Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Central Statistic Organisations (2018). Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey 17 – 2016.

[5] Ministry of Education, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (2016). National Education Strategic Plan (2021 – 2017).

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://www.unicef.org/afghanistan/education

[8] UNICEF (2016). State of the World’s Children 2016.

[9] Human Rights Watch (2020). “Disability Is Not Weakness” - Discrimination and Barriers Facing Women and Girls with Disabilities in Afghanistan.

[10] UNICEF (2016). State of the World’s Children 2016.

[11] Ministry of Education, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (2016). National Education Strategic Plan (2021 – 2017).

[12] Human Rights Watch (2017). “I Won’t Be a Doctor, and One Day You’ll Be Sick” - Girls’ Access to Education in Afghanistan.

[13] http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/af

[14] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and REACH (2018), Hard to Reach Assessment Afghanistan.

[15] Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (2020). Education Under Attack 2020 - A Global Study of Attacks on Schools, Universities, their Students and Staff, 2019-2017.

[16] Ibid, p. 99.

[17] UN General Assembly and Security Council, “Children and Armed Conflict: Report of the Secretary General,” S/509/2019, June 2019 ,20, para. 23; UN General Assembly and Security Council, “Children and Armed Conflict: Report of the Secretary General,” A/865/72–S/465/2018, May 2018 ,16, para. 26.

[18] Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (2020). Education Under Attack 2020 - A Global Study of Attacks on Schools, Universities, their Students and Staff, 2019-2017, p. 99

[19] UNICEF (2019). Afghanistan sees three-fold increase in attacks on schools in one year – UNICEF.

[20] UNOCHA (2019). Humanitarian Response Plan Afghanistan – 2021 – 2018.

[21] UN General Assembly and Security Council (2020).The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security - Report of the Secretary- General. A/993/74–S/809/2020.

[22] What Works to Prevent Violence (2017). Despite a new law which bans it, corporal punishment is rife in schools throughout Afghanistan.

[23] Human Rights Watch (2017). “I Won’t Be a Doctor, and One Day You’ll Be Sick” - Girls’ Access to Education in Afghanistan.