It was the evening of June 4, 10 days after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis that sparked protests across the United States. Activists in her neighborhood had organized a march, like hundreds that had sprung up across the United States to protest police brutality. She had heard about the local protest on Instagram and wanted to participate – in the neighborhood where she was raised and now worked as a teacher. “I felt really comfortable going because it was right in the neighborhood where I live.”

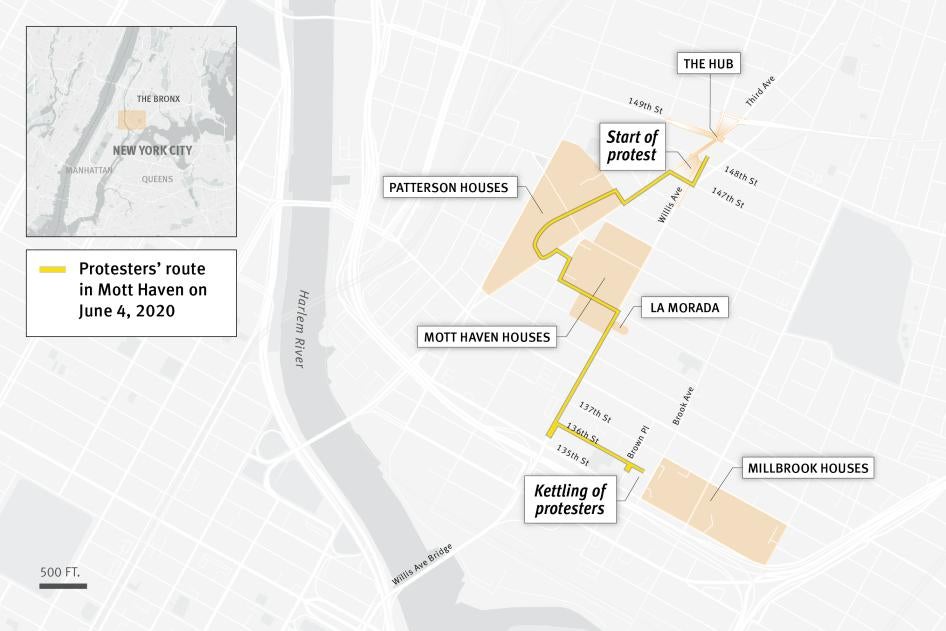

When she arrived at the corner of 149th Street and 3rd Avenue, in the Bronx neighborhood known as Mott Haven, a group had already gathered. The group started to walk along 3rd Avenue at around 7 p.m., through a number of housing projects as the leaders talked about the history of the neighborhood and the struggles faced by residents. As they headed down Willis Avenue, they were blocked by police so made a U-turn and then turned onto 136th Street. They tried to make a right turn on Brown Place but were blocked by police cars and vans. So, they continued on 136th Street, which sloped downward. More police sped by on bikes as the protesters walked down the hill. At the bottom, on Brook Avenue, the police officers jumped off their bikes and used them to form a barricade. With the path forward now blocked, the group looked to turn back. But police had moved in behind the protesters, on foot and with cars.

“I start to text my mom to let her know I’m stuck, and they have us ‘kettled’ in and we can’t go anywhere,” Chantel said. “It was very uncomfortable.”

Law enforcement officers responded to many of the protests held across New York City and the United States after the killing of George Floyd with violence, excessive force, and abuse. Human Rights Watch’s report on the Mott Haven protest, based on interviews or written accounts from 81 people who participated and a review of 155 videos, concludes the police not only used excessive force, but that the response to the protest was planned in advance.

Chantel and the other protesters were now packed together, blocked in the back and front. Police in the rear began shoving people forward, while the police in front were pushing back. “People were getting pushed, elbowed, and people are losing their footing,” said Chantel.

Chantel started to video the melee on her phone, but when she saw a police supervisor – identifiable by his white shirt, worn by the highest-ranking officers – smack a phone out of someone’s hand, she quickly put her phone away.

Over a loudspeaker, a recording announced that it was now 8 p.m., the curfew imposed recently by the mayor in response to looting in other parts of the city.

Then things turned ugly.

Police officers leaned over the line of bicycle police, whaling on protesters with their batons. “One of the officers, I saw him before he hit me,” Chantel said. “He was hitting a bunch of people. It was so aggressive, I was shocked.” Chantel’s lip was split by a blow from a baton; she was hit on her fingers, too.

A police officer hit a white man next to her. “You wanted to hang out in the ‘hood?” the officer told the man. “Well, welcome to it.”

Protesters were putting their hands up saying, “Don’t shoot!” Chantel could hear bones crack as the blows rained down. Police officers were jumping on parked cars to beat down on people; pepper spray wafted through the mayhem.

Chantel clutched a Black man next to her as he was being pummeled. “Every time he got hit, I felt the hit and now I’m feeling his tears on my face. I just kept telling him, ‘I got you, I’m not gonna let you go,’ and he just rested his chin on my forehead and held me tight.”

Police began arresting people, zip-tying their hands and sitting them on the ground to wait for transport.

“I kept saying, ‘I want to go home, I live in the neighborhood, I’m an educator, I’ve been trying to go home since 7:30.’ I kept repeating that over and over, like 100 times.”

Chantel knew some of the police from the neighborhood – police officers she’d see on the walk to work, at the local grocery store or deli, even officers that came once to speak at Career Day in her class. “That was very overwhelming for me. So when I was saying, ‘I live in the neighborhood, I’m an educator,’ I was begging them for help.”

Eventually a supervisor grabbed her by the wrist and started leading her out of the snarl of protesters and cops. Chantel believed he was going to arrest her. But then another police officer came over to help. He took her to the edge of the protest, pushed her, and told her to hurry up and go home. Chantel isn’t sure why the officer chose to let her go, unlike the 263 people who were arrested and detained during the protest.

She went home, hurt and terrified. She couldn’t sleep, troubled by the fate of the others. She got up at 5 a.m., gathered some snacks, got in her car, and started making rounds of the Bronx police stations. No one could tell her anything about the fate of her fellow protesters. She was told to go to central booking in Queens, where she saw arrested protesters trickle out. “That was another shocker. You saw people coming out with head injuries, shirts ripped, bruised arms.” She took one protester with a head injury to Urgent Care.

Chantel has been anxious since that night. “I get very emotional; sometimes I’m crying for no reason. I often think about the man that I was holding or seeing a pregnant woman dragged by her shirt out of being kettled. And I just remember officers hitting people. I remember hearing someone’s bone break. I never heard someone’s bone break before that.”

“It was just innocent people that got really hurt.”