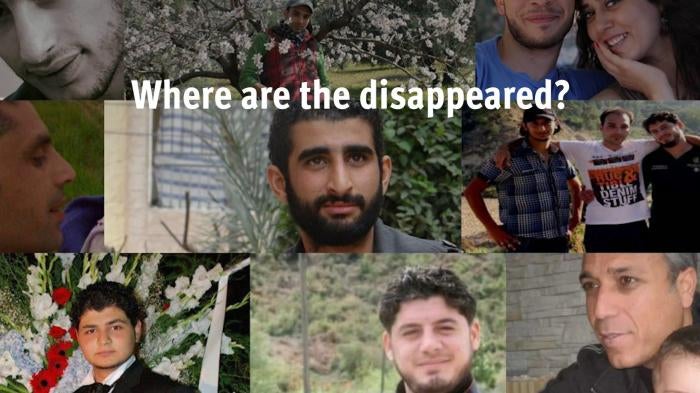

(Beirut) – Local authorities in northern Syria have failed to advance efforts to find people kidnapped by ISIS more than a year after its territorial defeat in Syria, Human Rights Watch said today. The authorities should promptly dedicate resources to uncover what happened to the thousands of missing people.

During ISIS’s reign in Syria, the armed group committed horrific abuses against the civilian population, chief among them the kidnapping and execution of thousands of people abducted from their homes, checkpoints, and workplaces. ISIS targeted people it saw as an obstacle to its expansion or resisting its rule. The kidnappings and disappearances spread fear and confusion, removed vocal opponents, and set an example for those who might have been tempted to resist.

“Local authorities in the Syrian areas once held by ISIS need to make those kidnapped by ISIS a priority,” said Sara Kayyali, Syria researcher at Human Rights Watch, “With ISIS defeated and many suspects in custody, the authorities have the access they need to the area and to the information they need. What is needed now is the political will to find answers.”

No segment of the Syrian population was left untouched. Human Rights Watch has documented abductions of Syrian government soldiers, Kurdish activists, and journalists affiliated with the opposition. Yet no authority has provided the resources or political will necessary to uncover what happened to the missing in Syria and elsewhere, or to seriously consider and engage the pleas from families to find out what happened to their loved ones.

In February 2020, Human Rights Watch published a report in which it urged local authorities to dedicate resources to this effort, including by creating a centralized system to reach out to families of the kidnapped, access key intelligence on ISIS suspects that may provide leads, and exhume mass graves.

On April 7, the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) in northeast Syria announced the creation of a working group to address the issue of detainees. Despite this positive step, it has not taken any other measures to prioritize discovering what happened to those apprehended by ISIS and last heard of in the group’s custody. The Syrian Democratic Council and its military arm, the Syrian Democratic Forces, are supported by the US-led anti-ISIS coalition.

Firas al-Haj Saleh, July 2013

Firas al-Haj Saleh, a public sector employee born in 1972, had been arrested twice by President Bashar al-Assad’s security forces for organizing anti-government protests and lost his job after the second arrest. Al-Haj Saleh helped lead opposition to the Islamic State (ISIS) when the group rose in Raqqa city in 2013.

On July 20, 2013, a car intercepted al-Haj Saleh and a friend while they were returning to his home after a night out in Raqqa city. The car took al-Haj Saleh to an ISIS headquarters in the city, the friend told al-Haj Saleh’s wife.

His family, including his wife, Ghadeer, have not heard anything about him since. Al-Haj Saleh’s son, Ibrahim, now 8, was 2 when his father was kidnapped. In 2018, his mother told Human Rights Watch Ibrahim barely remembers his father:

With Daesh [ISIS], you cannot negotiate. No matter how much you hear about it, no matter how much you see, it’s not the same as for those who have lived with them. It’s been 4 years, 10 months, and 3 days – not a single piece of information, not a single sign.

Abdallah Khalil, May 2013

Abdullah Khalil, born in 1961, was a long-time human rights defender. When the Free Syrian Army (FSA), a coalition of armed anti-government groups, took Raqqa city from the Syrian government in 2013, Khalil returned to the city and briefly served as the head of the local civil council overseen by the Syrian National Coalition (SNC), a coalition of anti-government groups founded in 2012.

On May 19, 2013, Khalil was abducted while on his way to al-Meshleb village, near Raqqa, at midnight as ISIS was emerging and consolidating power in the area. Official ISIS documents obtained by Zaman al-Wsl, a Syrian news outlet affiliated with the anti-government opposition, indicate that the Islamic State was most likely behind his kidnapping.

The last that Khalil’s family heard about his whereabouts was in 2016, when a nurse who used to work at Tabqa prison under ISIS told relatives that he had seen Khalil in the prison, and that he was still alive. Since then, Khalil’s wife has not received any credible information regarding her husband, despite having raised the case with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Kurdish authorities after ISIS was defeated in Raqqa city.

Describing the impact of Khalil’s kidnapping on the family, his wife said:

There are no words to describe the moments we went through – difficult, grim moments of pain, pure pain. [Our daughters] Safa and Marwa, when they see anyone who knew their father, they feel broken. I see it in their eyes, in their look, because they do not know their father, they were 7 when he left. They only see him in pictures. But no memories. They still live hoping that their father will come back.

Adnan and Idris Kashif, July 2013

On the afternoon of July 20, 2013, Adnan Kashif, an agricultural engineer living in Raqqa city, left the house to buy toys for his children to celebrate their birthdays. By 9 p.m., he had still not returned.

Kashif had been walking with a group of friends when a group of armed ISIS fighters intercepted them and drove off with Kashif and one of his Kurdish friends. The kidnappers told the other friends that they planned to use them in a prisoner exchange with the Kurdish-led People’s Protection Units (YPG), and that if they wanted more information to follow up at the governorate’s ISIS headquarters.

Thirteen days later, ISIS also took Adnan’s brother, Idris Kashif, from the streets in Raqqa city. The last Adnan’s wife heard about her husband was in 2016 when a former detainee called her on WhatsApp and told her that her husband was with him in an ISIS detention facility near a village in northeast Syria called al-Akirshi. She told Human Rights Watch:

There is no reason now for him to still be missing. We have four girls, and a son. He was our backbone. I need to know if he is dead or alive. His children need to know. Or give me an official contact I can apply to, or register him with as a missing person, so they could go look for him and find him and bring him back to me.

Father Paolo Dall'Oglio, July 2013

Father Paolo Dall’Oglio, 64, is an Italian Jesuit priest who spent three decades in Syria renovating a monastery before being expelled by the Syrian government in 2012 for condemning its treatment of protesters and other abuses. Among Syrians, Dall’Oglio was widely considered a respected activist and a prominent voice for peace and coexistence. He returned to Syria in late July 2013, crossing through Gaziantep to visit areas that were no longer held by the government.

In late July 2013, Dall’Oglio entered Raqqa city, apparently to negotiate the release of peace activists. Local activists and news reports said that at 11 a.m. on July 29, Dall’Oglio went to the Raqqa governorate building, then under ISIS control, to request more information regarding detained activists. He was not seen again.

On July 29, 2019 – the sixth anniversary of his kidnapping – the US announced up to US$5 million as a reward for anyone who could provide information about five kidnapped Syrian religious figures, including Dall’Oglio.

Muhammad Nour Matar, August 2013

Muhammad Nour Matar, 20 at the time, was last seen in Raqqa city on the night of August 13, 2013. Matar and his older brother Amer, a journalist, had been filming and documenting ISIS abuses in the city.

That night, a car bomb exploded near the old train station in Raqqa, where he was filming. Initially, his family feared he had been injured or killed. Amer Matar arrived in Raqqa the next day. The medical team at the site gave him his brother’s charred camera. There were no bodies at the site.

Matar’s family later heard from detainees released from ISIS jails that they had seen him in the governate administration building that ISIS used for interrogations, and in al-Sad prison in the town of Tabqa, which ISIS controlled.

During the military campaign to drive ISIS from Raqqa, Amer Matar began searching prisons abandoned by ISIS for any information about his brother.

“The SDF arrested hundreds of ISIS members, and we tried to communicate [with them]; they never responded or took this seriously,” Amer Matar said.

Samar Saleh and Muhammad al-Omar, August 2013

The Syrian government detained Samar Saleh, 25 at the time, in 2012 for her activism with the anti-government student movement at Aleppo University. After her release, she managed several shelters in Aleppo schools for displaced families from the Aleppo countryside. Fearing re-arrest, she went to Cairo University to study for a master’s degree in archeology.

In 2013, she returned to northern Syria to see her family. On August 13, when she was driving back from a family visit in the car with her fiancé, Muhammad al-Omar, and her mother, a jeep stopped them in al-Atareb, Aleppo. Masked gunmen got out of the car and took Saleh and al-Omar but let Saleh’s mother go.

The next day, Saleh’s parents visited al-Dana to ask about their daughter. ISIS officials there told them it was a routine investigation, and that she would be released soon. They asked why she had gone to the United States before the conflict, and what she did for a living. The next time her parents went there, ISIS denied that they had Saleh. Since then, her family has not received any substantial information regarding Saleh or al-Omar’s whereabouts.

Members of the Imam family, August 2013

ISIS members detained Muhammad Muhammad Imam, then 34, and his brother Farouq Muhammad Imam, 29, and their cousin Nechervan Muhammad Imam, 21, from a checkpoint in Hatara, in the Raqqa governorate on August 14, 2013.

The three worked together on a farm in Raqqa governorate. They owned a tractor that they would take to work the field. On August 14, the three went to work as usual. A few hours later, one of the Imams’ colleagues returned and told the family that a local ISIS emir had taken the three men after they refused to give him their tractor. Imam Muhammad Imam, Nechervan Imam’s father, and his brother immediately went to Raqqa governorate to follow up. Officials at ISIS headquarters turned them away and told them not to create trouble.

After the SDF and US-led coalition started to retake territory in Raqqa governorate, Imam said, they visited a number of times and asked contacts at the highest levels of the SDF as well as in Syrian government-held areas about the three relatives, but learned nothing.

“We don’t want anything – we just want them to come back,” Imam said. “It’s been five years without any calls, or anything, and we are tired of asking, tired of telling the same story over again, tired of not having answers. For five years, our hearts are burning, and no one can relieve our pain.”

Ayman Shaaban Mustafa; Hussein Aly Mustafa, August 2014

ISIS fighters took cousins Ayman Mustafa, 18 at the time, and Hussein Mustafa, 23, from their home in the northern Raqqa countryside on August 2, 2014 after they helped government soldiers hide from ISIS.

Six days before, as ISIS approached the headquarters of the 17th Division, about 400 government soldiers sought refuge in the family’s cornfields. After Ayman Mustafa told his father, Shaaban Mustafa, that they were hiding there, he and Hussein Mustafa took water to the soldiers. The family let them stay until nightfall.

The morning of August 2, the two cousins were working in the fields, when ISIS took them.

Ayman Mustafa’s parents immediately went to the nearby ISIS headquarters in Hazima and asked about them. The ISIS members there told him the two had been moved to Raqqa city, to the detention center called Point 11, also known as the Black Stadium.

The family had no further news of the cousins. Shaaban Mustafa and his family had fled from bombing during the campaign to retake the area from ISIS and been displaced from their home for over a year when Human Rights Watch interviewed them in 2018. Despite regular inquiries to the intelligence services and the Asayish, the family learned nothing more about the two cousins.