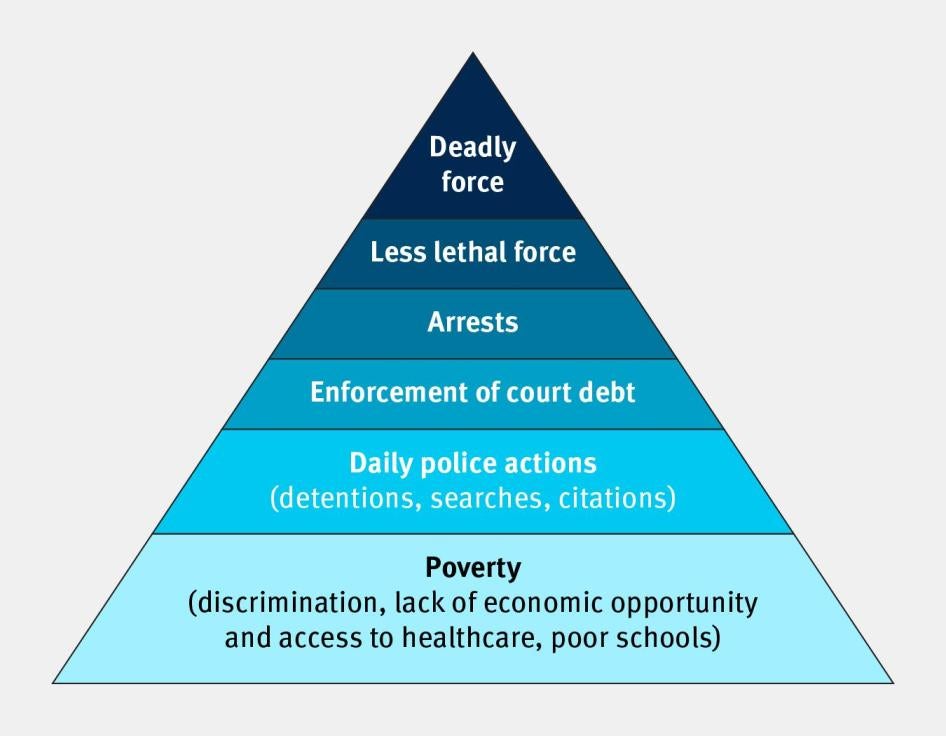

In the wake of the killing of Terence Crutcher, an unarmed black man, by a Tulsa police officer in September 2016, Human Rights Watch conducted an investigation into everyday policing in Tulsa, looking at its impact on people of color and poor people. We found substantial disparities in treatment by police of black and white people and differences in policing in poor neighborhoods and more affluent neighborhoods.

As one example, a Tulsa police officer described to Human Rights Watch responding to a call and finding a group of officers had stopped a black man walking down the sidewalk in North Tulsa, the part of the city with the largest black population and the highest rates of poverty. That man had tried to walk away and a confrontation that could have resulted in forceful action was emerging. When the officer arrived, he asked the officer who had initially stopped the man what violation of law they suspected that justified the stop. The officer said there was no violation, but “we just wanted to find out who he was.”

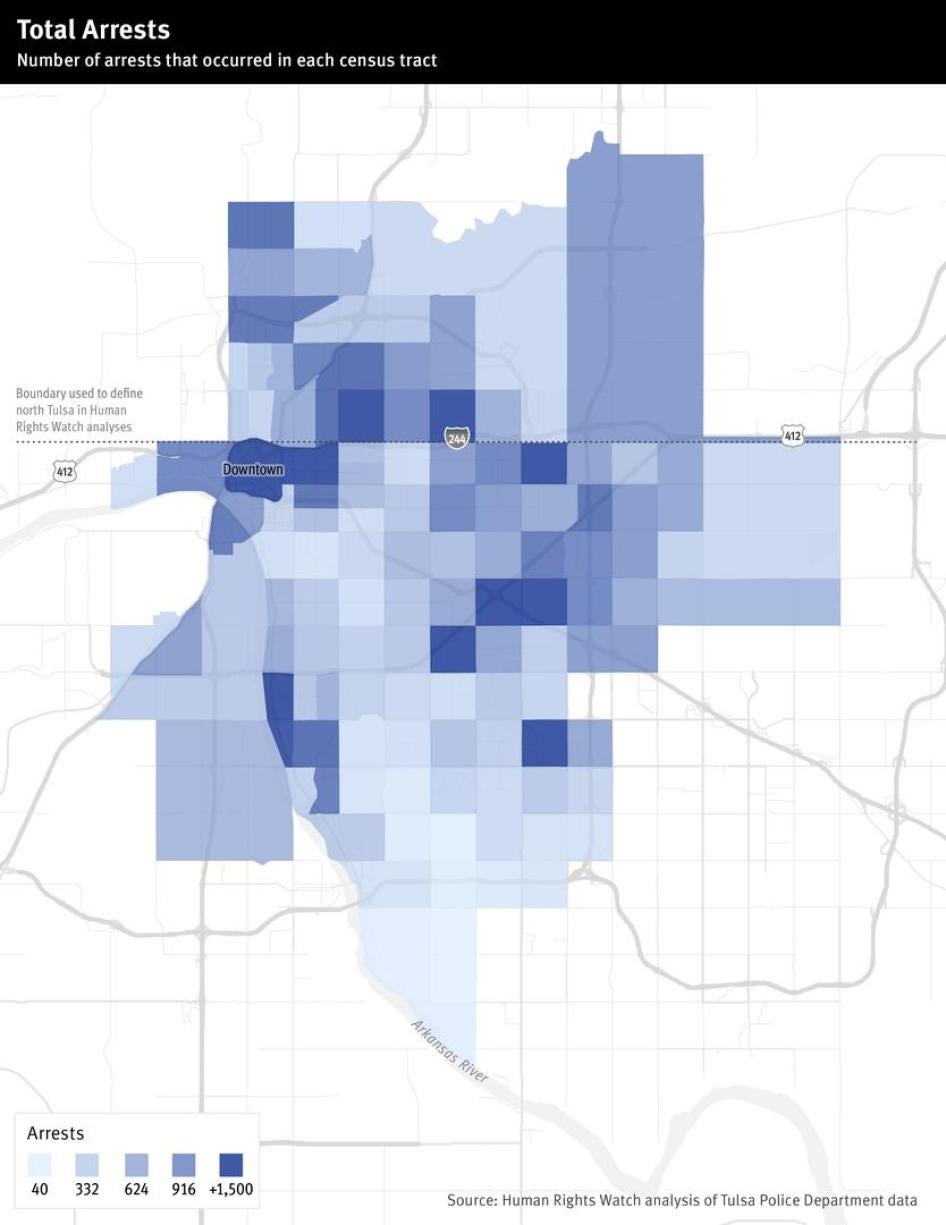

Arrests

Tulsa Police arrest black people at a rate 2.3 times greater than the rate at which they arrest white people. Black people are 17 percent of the population and 36 percent of all arrestees; white people are 65 percent of the population and only 58 percent of all arrestees. Police arrest black people for warrants, including a high percentage of “failure to pay” warrants, 2.6 times more frequently than white people; for drugs, 2.4 times more frequently; for weapons, 4.3 times more frequently; and for violent crime, three times more frequently.

While some of the arrest disparity may be attributable to higher rates of actual crime in poverty-stricken parts of the city where black people tend to live, it is also a reflection of a greater police presence in these communities. This results in stops and arrests, often for petty offenses, such as the possession of drugs or warrants connected to other petty underlying offenses or failure to pay court fees, fines, and costs. Some of these offenses are ones that should not be criminalized in the first place. Many of these offenses are connected to poverty factors that can lead to crime. Violent crime accounts for less than 10 percent of all arrests while warrant arrests alone make up nearly 40 percent. Warrants, drug, and weapons offenses are generally uncovered by police-initiated activity like stops and searches.

Stops

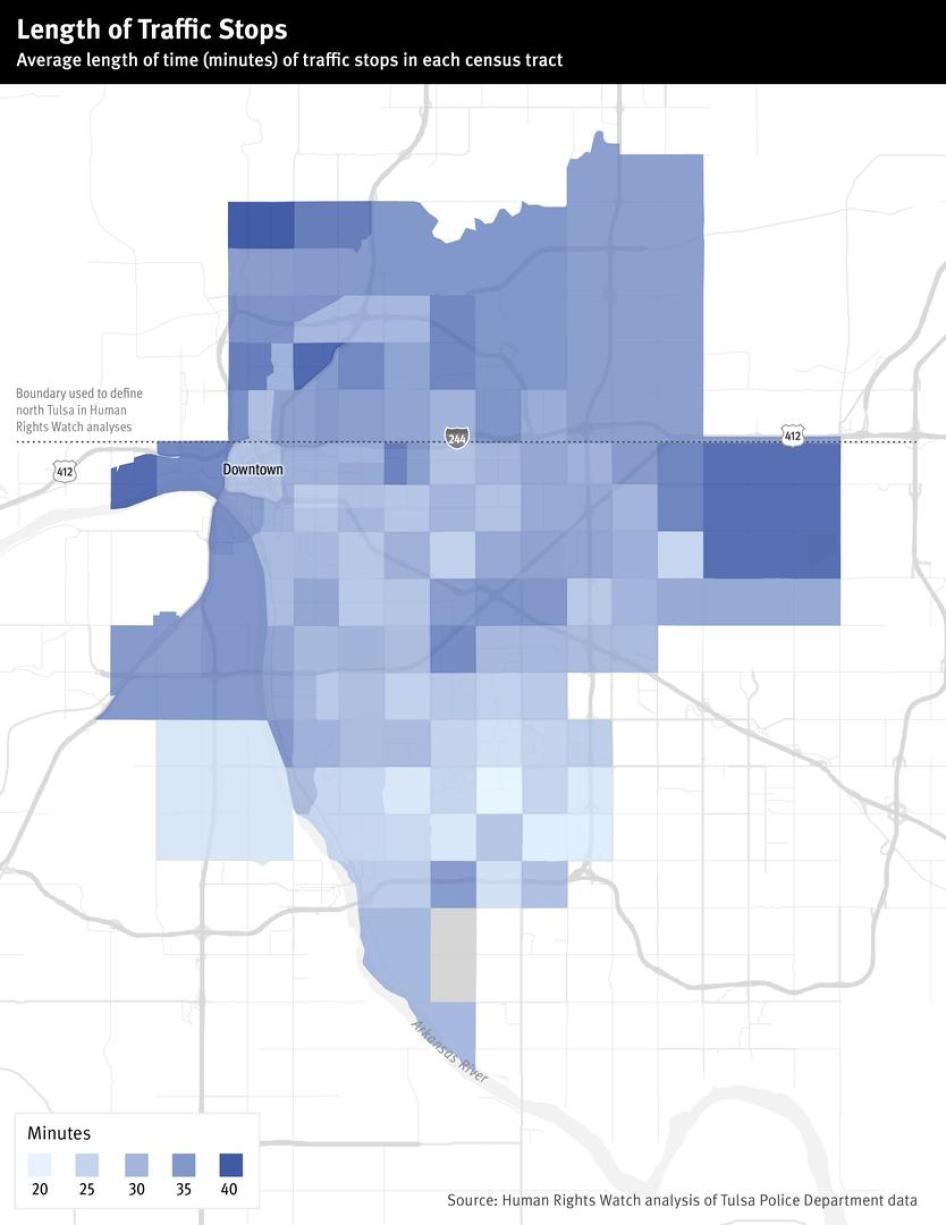

Tulsa Police data on pedestrian and vehicle stops did not include the race of the person stopped or sufficient information to connect stops to subsequent arrests. It did have locations. Human Rights Watch found wide disparities by neighborhood in rates of vehicle stops. There were 10 census tracts which experienced over 200 stops per 1,000 residents each year. These tracts were high poverty neighborhoods and primarily neighborhoods with greater non-white populations. Most tracts had less than 100 stops per 1,000 residents per year. A few tracts, with wealthier residents and mostly white populations, had fewer than 15 stops per 1,000 residents per year. One tract, with a 2 percent black population and a 2 percent poverty rate, had only 2 stops per 1,000 residents per year.

The majority of black Tulsans lived in neighborhoods with high rates of police stops. Many black people reported to Human Rights Watch their experience of being stopped without justification by police, often cited for minor violations, or being released after a humiliating encounter.

Many people Human Rights Watch spoke with reported aggressive conduct on the part of police in North Tulsa. Black residents reported police sometimes approaching them with guns out, ordering them from their cars, or pressuring them to agree to a search of the car or of the individual. One Latino Tulsan described police stopping him for a traffic violation in North Tulsa, then making clear that they would give him a ticket if he did not allow them to search his car. Others reported similar experiences. One officer told us that other officers admitted to pressuring people to give them permission to search during every stop.

Tulsa Police did not provide data on searches or other details of traffic and pedestrian stops. However, using start and end times of stops, Human Rights Watch was able to calculate their average duration, reflecting how involved and potentially abusive they were. Neighborhoods in North Tulsa, with high black and high poverty populations, consistently had longer stops than in whiter wealthier parts of South Tulsa. Average stops in some North Tulsa neighborhoods were about double the length as those in some South Tulsa neighborhoods.

Citations

Racial disparities in ticketing exist, though they are not as extreme as arrest disparities. Black people were cited 1.4 times more frequently than white people. Certain types of tickets, specifically speeding or other moving violations that are observable to police, occurred at roughly the same rates for black and white people. However, tickets for no license or for no proof of insurance were given to black people at a rate twice that of white people. Those types of violations reflect poverty, as they are connected to inability to pay. They also may reflect police detention decisions—license and insurance violations are discovered after a stop for some other reason, possibly using some minor violation as a pretext to stop and search for evidence of a more serious crime. License and insurance violations with no accompanying moving violations had even higher racial disparities.

Dubious Connection to Crime Control

Enforcing warrants for “failure to pay” court debt and subjecting people to frequent, degrading stops and citations, is not likely to reduce serious crime. There is some evidence that this style of policing damages trust and may even increase crime. It certainly can increase neighborhood tension and the impacts of poverty that contribute to criminality.

The addition of more officers in Tulsa is likely to increase the number of stops, searches, citations and arrests and maintain or increase the disparities that have harmed the black community.