In April 2016, the police found the bodies of Xulhaz Mannan and Tonoy Mahbub, two prominent LGBT rights activists, in an apartment in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. This week, police arrested one of the main suspects in the murder, stating that the killers had plotted the attack over the past six months.

Mannan and Mahbub’s murders form part of a string of similar attacks on progressive bloggers and political commentators, and sent shivers through lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities in Bangladesh – leading dozens of activists to flee the country.

Mannan was the charismatic ex-president, co-founder and publisher of Roopban, Bangladesh’s first LGBT-themed magazine, launched in 2014. He was a visible and openly gay human rights activist who supported and protected gay and trans people even in the face of threats against the community.

His close friend Mahbub was also an openly queer activist. The two were hacked to death with machetes in Mannan’s apartment. An Al-Qaeda affiliate claimed responsibility, calling Mannan a “pioneer of promoting homosexuality in Bangladesh”.

The gay and trans community in Bangladesh is under constant pressure. “Visibility can be life-threatening,” Boys of Bangladesh, an LGBT rights organisation, warned in 2015.

Even subtle displays of activism can attract unwanted attention. Visibility has become even riskier as the authorities have repeatedly failed to support freedom of expression – evidenced by police indifference to the killings of progressive public figures and new laws passed to stifle online content.

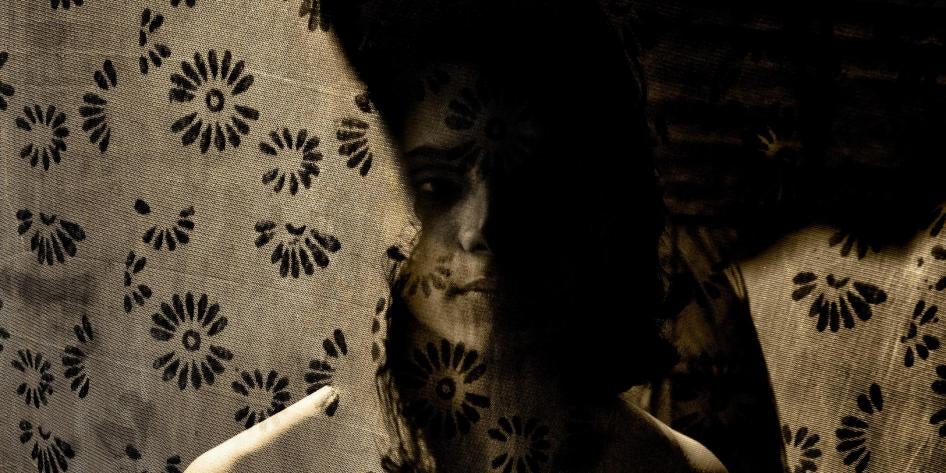

Amid such threats and attacks, queer activists in Bangladesh have developed creative strategies to raise awareness, educate the public and carve out safe spaces for expressions of diversity.

Visual arts have been an effective tactic.

In 2015, Boys of Bangladesh began a cartoon series called Dhee, the name of the main lesbian character. Activists used the cartoon series in private events across the countries to teach about diversity, sexual orientation and gender identity, and acceptance.

Audiences first meet Dhee as a schoolgirl and then follow her as she becomes a woman – including her attraction to a female classmate – and read about the sharp rejection and rebuke she faces for her “unnatural” feelings.

The story ends on a cliffhanger – the authors wanted audiences to think and discuss what Dhee’s opportunities might be amid very real social pressures in contemporary Bangladesh.

But while Dhee may have been changing hearts and minds incrementally, the government of Bangladesh has continued in its antipathy toward sexual and gender diversity.

The National Human Rights Commission of Bangladesh has documented physical and sexual assaults on LGBT people by the police.

Government initiatives to improve opportunities for hijras (a community of transgender women) through official third gender recognition were derailed in practice, when they experienced humiliation and abuse at the hands of doctors.

At a United Nations review, the Bangladeshi government accepted a recommendation to enhance police training in terms of dealing with women and children, but rejected the call to protect LGBT people, stating “sexual orientation is not an issue in Bangladesh”.

Bangladesh retains a law that criminalises same-sex conduct, or “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” – the same remnant of British colonial law that India struck down last year.

But LGBT activists are not giving up.

Dhee’s adventures have taken hold amongst LGBT Bangladeshis – and the authors are now asking the world for help to continue the series. They have opened a campaign to raise funds to produce a new cartoon volume.

As one organiser wrote anonymously in an article for the London School of Economics: “People who identify as queer are more than just a statistic, or an alphabet in an acronym, or a policy, or a minority group that you place behind a comma. We are members of your community, of many large communities.”

The point was simple, they wrote: “We hold great knowledge and have radical stories to tell. And nobody can tell these stories like we can.”