(Jerusalem) – The Palestinian Authority’s repeal of certain discriminatory provisions against women in March 2018 is a good first step toward what should be the repeal of a series of such measures, Human Rights Watch said today. Other forms of discrimination include birth registration, personal status laws, and gaps in accountability for domestic violence. Palestine should make such reforms ahead of the first review of its record on women’s rights before the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women – the body that monitors the international women’s rights treaty – in Geneva in July.

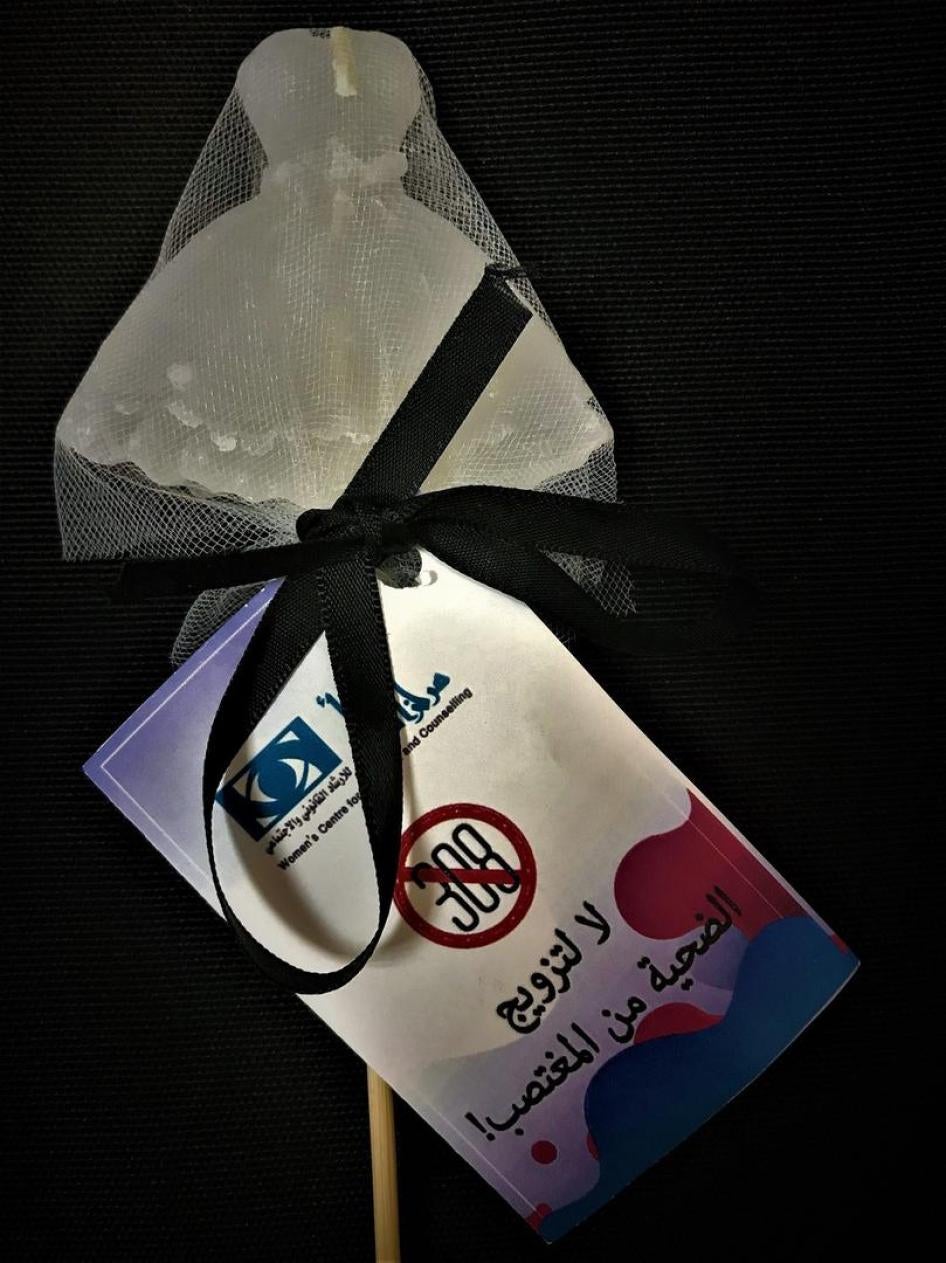

On March 14, 2018, the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, signed Law no. 5 of 2018, which repealed article 308 of the 1960 Penal Code enforced in the West Bank. Based on an assessment by the head of a women’s shelter, the law had allowed alleged rapists to escape prosecution and could allow convicted rapists to avoid imprisonment if they married their victims. The new law also amended article 99 to prohibit judges from reducing sentences for serious crimes, such as the murder of women and children.

“The Palestinian Authority has finally closed disturbing colonial-era and other loopholes that could allow rapists to escape punishment if they married their victims, and to treat murders of women as a lesser crime than murders of men,” said Rothna Begum, Middle East women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Other countries in the region that still have provisions that could allow rapists to go free by marrying victims, including Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, and Syria, also should repeal them.”

Human Rights Watch in April discussed the status of women with members of the Palestinian Ministry of Women’s Affairs and the Public Prosecution Office. Human Rights Watch also met with 18 representatives of various women’s rights groups, human rights organizations, and international organizations in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Systematic abuses associated with Israel’s 50-year occupation including institutionalized discrimination, home demolitions and restrictions on movement fundamentally undermine the rights of Palestinian women in the West Bank and Gaza. Human Rights Watch has documented the impact of these practices in a submission for Israel’s review of its record under the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in October 2017.

The new amendments do not apply to pending court cases. It is not clear how many alleged or convicted rapists have been able to escape prosecution or conviction under article 308. Ikhlas Sufan who directs a shelter for victims of violence in Nablus, told Human Rights Watch that between 2011 and 2017 prosecution for rape has been halted in 60 cases – in which the shelter was helping the women – after the alleged rapist agreed to marry the victim. In 15 of these cases the women later divorced these men.

Both Sufan and the Women’s Centre for Legal Aid and Counselling (WCLAC) warned that families may still coerce women and girls who become pregnant to marry the men because of barriers to getting birth certificates for children born out of wedlock and the criminalization of abortion.

The Public Prosecution’s 2017 annual report says that 11 out of 14 murders of women in 2016 and 2017 in the West Bank – excluding Area C and East Jerusalem, where the Palestinian Authority has no oversight – were committed by a relative. It is unclear whether any of the alleged killers claimed the need to protect their family “honor” as a defense.

Dareen Salhieh, chief prosecutor of the Family Protection Unit in the Public Prosecution, said that they conducted gender-sensitive training for the police and prosecutors in the West Bank, who then investigated and referred cases of killings of women by their husbands or families to courts. The judges, however, often reduced the sentences of defendants who had been found guilty. The 2014 Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights study found that judges in first instance courts reduced sentences on claims of “honor” killings in 29 out of 37 rulings, in a random sample of cases between 1993 and 2013.

Training judges and closely monitoring convicting and sentencing of gender-based violence cases will be important to end impunity, Human Rights Watch said.

In another key reform on March 5, Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah announced the cabinet’s decision to allow women who have custody of their children, to open bank accounts for them, transfer their children to different schools, and apply for their passports.

However, the two laws that apply to Muslims, the Jordanian Personal Status Law No. (16) of 1976 enforced in the West Bank, and the Egyptian Family Rights Law No. (303) of 1954 enforced in Gaza, do not make the best interests of the child the primary concern when determining which parent the child should live with and which guardianship rights each parent should have. Under these laws, fathers retain guardianship rights even when the child is officially living with the mother, and the child can be automatically removed if the mother remarries, but not the father.

As guardians, fathers can withdraw money from a child’s bank account opened by the mother even if the child lives with the mother, but mothers cannot do the same if the child lives with the father. A woman also needs the father’s permission to travel abroad with her child. Both family laws also discriminate against women in marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

Palestine also does not have a domestic violence law, which makes it difficult to adequately protect survivors of domestic violence or prosecute abusers. The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) 2011 national survey of 5,811 households on gender-based violence found that 37 percent of married women who responded had been exposed to at least one form of violence by their husbands.

Since 2006, when Human Rights Watch reported on the inadequate response to domestic violence in Palestine, the Palestinian Authority has taken some positive steps in the West Bank by creating specialized Family Protection Units in police stations and family protection prosecutorial units. But the lack of a legal framework to address domestic violence has hampered the work of such units. “We don’t have protection orders or prevention procedures” to help protect women, said Dareen Salhieh, the chief prosecutor.

Palestinian authorities are considering a draft Family Protection Law that would remedy this if amended in line with international standards. Such a law should set out the government’s key obligations to prevent violence, protect survivors, and prosecute abusers, Human Rights Watch said. It should criminalize marital rape, revise the definition of the “family” to include non-marital partners, and provide funding to enforce the law.

“Palestinian authorities have a critical window to pass needed reforms before international experts scrutinize their record on women’s rights in July,” Begum said. “A comprehensive domestic violence law and reforms to personal status laws are essential for demonstrating a commitment to women’s equality and protection.”

Laws in Palestine and the Palestinian Authority’s Limited Reach

Laws in the West Bank and the Gaza include a combination of unified laws promulgated by the Palestinian Legislative Council and ratified by the president. If no unified law has been issued, existing Jordanian, Egyptian, and former British Mandate laws still apply.

The Jordanian Penal Code No. (16) of 1960 and the Jordanian Personal Status Law No. (16) of 1976 are enforced in the West Bank, while the British Mandate Criminal Code Ordinance No. (74) of 1936 and the Egyptian Family Rights Law No. (303) of 1954 are enforced in Gaza. In East Jerusalem, which Israel unlawfully annexed in 1967, Israel has applied Israeli civil law, though it remains occupied territory under international law.

Article 9 of the Palestinian Basic Law, promulgated in 2003 and last amended in 2005, provides for equality before the law without distinction based upon sex. The full Palestinian Legislative Council has not convened since 2006, but article 43 of the Basic Law allows the Palestinian president to issue presidential decrees until it reconvenes and can review all such legislation. Some presidential decrees have included amendments to Gaza’s laws, but Hamas, as the de facto authority there, has not applied them and instead issued separate decrees.

The Palestinian Authority’s reach is limited as it cannot enforce its laws in Area C, the 60 percent of the West Bank where the Israeli military has exclusive control, or in East Jerusalem, where Israel has applied Israeli civil law, though it remains occupied territory under international law. The Palestinian Authority also cannot apply its laws in Gaza, which is under the control of Hamas. Women’s rights organizations and government officials told Human Rights Watch that some men who commit violence against women flee to Area C, East Jerusalem, or Israel to escape prosecution.

The UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women noted in her 2017 report that “the occupation is a real obstacle to the State’s [of Palestine] due diligence obligation to prevent violence against women in areas where it does not have full jurisdiction, because of the fragmentation of the areas under different control and the political divide between the Gaza de facto authority and the Government of the State of Palestine.”

Women in East Jerusalem who experience domestic violence face particular barriers. Oheila Shomar, director of Sawa Organization, nongovernmental organization that supports survivors of domestic and sexual violence, said that: “Many Palestinians don’t want to cooperate and fear what will happen to them and how the [Israeli] police will use their situation to harm the family if they file a complaint. If a woman tries to go to the [Israeli] police, the family and community stigmatize her for going to the occupation and harming her family."

Children Born Out of Wedlock

Palestinian authorities require a marriage certificate to register births. In the West Bank, mothers can obtain birth certificates for their children born out of wedlock, but these children cannot take a family name, exposing them to stigma. Even if they are given up for care, their foster families cannot officially adopt them or give them their family name. The Women’s Centre for Legal Aid and Counselling (WCLAC) said they knew of 27 such children in the Social Development Ministry’s care.

Randa Siniora, director of WCLAC, warned that families may still try to force women and girls to marry their alleged rapists or men with whom they have had extramarital sex “unless the authorities provide safe, legal abortions and the registration of children born outside of wedlock.”

The head of one shelter for victims of violence said they advised a 22-year-old woman who came to them six months pregnant to marry the father to help register the child under the father’s name. She did and divorced him a week later.

Palestinian authorities should stop requiring a marriage certificate to register a birth, Human Rights Watch said. They should allow women to register their children with a family name of their choice and ensure that children don’t suffer discrimination due to the parents’ marital status.

Criminalization of Abortion

The 1960 Penal Code enforced in the West Bank and the 1936 Penal Code enforced in Gaza both criminalize abortion. Women can receive reduced sentences for an illegal abortion under the 1960 Penal Code if they cite “honor” as the reason.

In practice, authorities may allow abortions in the first four months of pregnancy in situations of rape or incest, or if the mother has a disability or her life is at risk. However, Sufan, the shelter director in Nablus, said, “it is difficult, the mufti [religious jurist], hospital, and court all have to agree to allow the abortion.” Salhieh, the chief prosecutor, said that prosecutors obtained permission for seven women to have abortions in 2017, all in cases in which the women alleged that the pregnancy was a result of rape or incest and they were in the early stages of pregnancy.

Palestinian authorities should decriminalize abortion, Human Rights Watch said.

Reduced Sentences in So-Called ‘Honor’ Killings

These killings relate to cases in which a family member kills a relative for a transgression that they claim breaches the family’s “honor.” WCLAC documented 23 killings of Palestinian women and girls in 2016 across Palestinian territory, many of which they said were based on “honor”, or the killer claimed it was. Women Media and Development (TAM) said in its 2016 report that the killings actually related to inheritance, revenge, or other reasons but that the killers claimed they related to family honor to receive a lighter sentence.

Several reforms in the past few years have attempted to tackle the judges’ use of various legal provisions to reduce sentences on the pretext of “honor.”

In 2011, Abbas issued a decree abolishing article 340 of the 1960 Penal Code, which allowed a sentence reduction for a man convicted of killing or attacking his wife or female relative if he alleged that he came upon her in the act of adultery or extra-marital sex. In 2014, the president issued a decree amending article 98 of the 1960 Penal Code, which allowed reduced sentences for those who committed a crime in a “state of great fury” [or “fit of fury”] resulting from an “unlawful and dangerous act by the victim.” The amendment prohibited the use of this defense “against a female on the grounds of honor.” The decree similarly amended article 18 of the 1936 Penal Code, which applies to Gaza.

But, as the public prosecutor pointed out in a 2014 report, judges in the West Bank often use article 99 of the 1960 Penal Code to reduce sentences by half in cases in which the victim’s family – in some cases like “honor” killings also the killer’s family – waives its right to seek prosecution. Article 99 provides reduced sentences for mitigating factors but does not set out what they are. In practice, courts consider that victims and their families have a right to waive the prosecution as a mitigating factor. A 2014 Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights study found that in 14 out of 37 rulings from the random sample of cases between 1993 to 2013, judges in first instance courts invoked article 99 to reduce sentences for killings of women where families withdrew their right to seek prosecution.

Law No. (5) of 2018 essentially closes this loophole by amending article 99 to prohibit the use of mitigating sentences in serious crimes against women and children. However, this amendment will not apply to cases pending when the amendment was passed. Salhieh said that the Public Prosecution has routinely appealed cases in which courts reduced sentences for killing women. The 2014 public prosecution report noted that in 90 percent of cases involving gender-based violence at first instance and appeal courts, the public prosecution appealed reduced sentences for “fit of fury” defense or mitigating factors that were not well-reasoned or they relied on a family waiver of prosecution.

Salhieh and Randa Siniora of WCLAC told Human Rights Watch about the prominent pending case in which the husband of Suha al-Deek, allegedly stabbed her 25 times, killing her in January 2014 in front of their children. In 2016, the first instance court in Nablus initially sentenced him for willful killing but used articles 97 and 98 to reduce his sentence to two-and-a-half years imprisonment. The public prosecution appealed, and the appeals court convicted him of premeditated murder and sentenced him to 25 years in 2017 but used article 99 and time served to reduce it to 10 years.

His lawyer appealed the case to the cassation court, which reduced his charge to willful killing and sent the case back to the appeals court. The appeal court then sentenced him to 15 years and again used article 99 to reduce his sentence by half. “We are appealing the case again to the Cassation Court,” Salhieh said.

The UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women said in her 2017 report that she was informed that perpetrators often also use article 62 of the 1960 Penal Code, which allows parents to “discipline” their children by general custom, as a defense against charges that they abused or killed their daughters.

Palestinian authorities should monitor the convictions and sentencing in cases of gender-based violence, including murders, to ensure that judges are not using other legal provisions to reduce penalties in such cases, Human Rights Watch said. They should also invest in gender-sensitive training for judges, particularly regarding violence against women.

Discrimination in Marriage, Divorce, and Decisions Concerning Children

The Council of Ministers’ March decision to allow women who have custody of their children to open bank accounts for their children, transfer their children to different schools, and apply for their passports is important progress, but women still have inferior status in the law. “These reforms are administrative procedures and are not complete,” Sabah Salameh, coordinator of the Muntada Forum to Combat Violence against Women – representing a coalition of 17 nongovernmental organizations – told Human Rights Watch. She said that because fathers remain the official guardian, under personal status laws regardless of whether they have custody, the fathers can withdraw money from their children’s bank account even when the mother opened it.

The 2004 Law on the Palestinian Child provides that the state, including the courts, must take the best interests of the child into account in all its actions. But the personal status laws discriminate against women by allowing fathers to retain guardianship rights even if the children live with their mother, and consenting that woman loses custody if she remarries.

Under personal status laws that apply to Muslims, men can have four wives, while women cannot marry without a male guardian’s permission, unless they have previously married, or else they obtain court approval to marry without a male guardian’s permission or against their guardian’s wishes. The laws also require women to obey their husbands – including where the husbands change their residence or forbid women from working – in return for their entitlements to maintenance and accommodation from their husbands. Men have a unilateral right to divorce, while women must apply to the courts for divorce on specific grounds.

Ikhlas Sufan, a director of a shelter in Nablus, told Human Rights Watch that “divorce cases can go on for two to three years because the husband can claim he wants to reconcile when he doesn’t really.” This relates to cases in which a woman may seek a divorce on the basis of “dispute and discord” under article 132 of the Personal Status Law in the West Bank or “harm” under article 97 of the Family Rights Law in Gaza provided the spouses undergo a mandatory mediation process. In the West Bank, even if the wife claims domestic violence, the court is required to attempt reconciliation, and should these attempts fail, turn the matter to arbiters who must likewise attempt reconciliation before recommending a divorce that apportions blame.

Human Rights Watch spoke to “Aisha,” whose name was changed for security reasons, a 30-year-old woman in Nablus who filed for divorce in 2016 after years of alleged domestic violence. She said the judge has not yet approved the divorce and has tried to reconcile the couple. She said: “The last time I went to court in March [2018], the judge gave him a month to improve himself to see if we can live together. The judge asked me, and I said, ‘No, after two years I don’t think we can reconcile’.”

An official from the Women’s Affairs Ministry said that in March, the government set up a ministerial committee to review the personal status laws.

The Palestinian authorities should ensure that women have equal rights with men in relation to marriage, divorce, residency (custody) and guardianship of children, and inheritance, Human Rights Watch said.

Inadequate Protections for Domestic Violence

The 2011 national survey by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), which surveyed 5,811 households on gender-based violence, found that 30 percent of married women respondents in the West Bank and 51 percent in the Gaza Strip had been exposed to at least one form of violence by their husbands. Fewer than one percent said they sought police help. Sufan said that domestic violence continues because “there are no legal or social deterrents” and the abuser “knows he can get away with it.”

Women’s rights groups have pushed for a domestic violence law since 2007. The Ministerial Harmonization Committee is reviewing a draft Family Protection Law, for which women’s rights groups have recommended improvements. Human Rights Watch reviewed the draft and found a number of positive provisions, such as creating emergency protection orders (also known as restraining orders) to prohibit contact between the accused and the victim, including removing the accused from the home; criminalizing forms of violence such as forced marriage; increasing penalties for physical violence; and setting out duties of the police and family protection units to accept complaints, investigate, and assist and protect survivors.

However, the bill does not explicitly set out the government’s key obligations to prevent violence, protect survivors, and prosecute abusers. The authorities should amend the penal code to define rape as a physical invasion of a sexual nature of any part of the body of the victim with an object or sexual organ, without consent or under coercive circumstances. The code should also indicate that sexual assault is a broader category and includes non-penetrative forms of assault, and explicitly criminalize marital rape.

The 1960 Penal Code in the West Bank excludes marital rape. “If a married woman says that her husband raped her, according to the penal code and the sharia courts, this is not a crime,” Salhieh said. “But if she has marks of the assault, we then investigate it as physical abuse instead of rape.” The penalties for physical assault that causes minor injuries are much lower than for rape, though.

The Palestinian authorities also should revise the definition of the “family” in the draft law to include non-marital partners and provide funding for enforcement, Human Rights Watch said. Lebanon’s Law on Protection of Women and Family Members from Domestic Violence, for instance, includes a mechanism to finance assistance for survivors and measures to protect and prevent domestic violence as provided in the law, and Morocco’s Law no. 103-13 on combating violence against women includes domestic violence by fiancés.

In recent years, almost half of the countries and autonomous regions in the Middle East and North Africa have introduced some form of domestic violence legislation or regulation, including Algeria, Bahrain, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, and Saudi Arabia. These laws vary in the degree to which they comply with international standards.

The Palestinian authorities should amend the draft Family Protection Law to ensure full protection of survivors and pass it expeditiously, Human Rights Watch said.

Palestine’s Obligations Under International Human Rights Law

Palestine acceded to the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in April 2014 without reservations or declarations, the only state in the Middle East and North Africa region to do so. Women’s rights groups have called for the Palestinian Authority to publish CEDAW in its Official Gazette, which would make it binding as domestic law under the Palestinian Basic Law.

CEDAW requires states parties to “take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs, and practices which constitute discrimination against women.”

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which Palestine also acceded to in April 2014 without reservations, outlines states’ obligations to register children immediately after birth and elaborates the right from birth to a name. Access to birth registration cannot be undermined by discrimination of any kind, including on the basis of the child’s, the parent’s, or legal guardian’s sex or other status, including marital status. It requires the government to ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration in all actions concerning children.