Summary

We all have to live in the borders of the boxes our dads or husbands draw for us.

—Zahra, 25-year-old Saudi woman, April 7, 2016

It can mess with your head and the way you look at yourself. How do you respect yourself or how [can] your family respect you, if he is your legal guardian?

—Hayat, 44-year-old former school principal, December 7, 2015

In Saudi Arabia, a woman’s life is controlled by a man from birth until death. Every Saudi woman must have a male guardian, normally a father or husband, but in some cases a brother or even a son, who has the power to make a range of critical decisions on her behalf.

As dozens of Saudi women told Human Rights Watch, the male guardianship system is the most significant impediment to realizing women’s rights in the country, effectively rendering adult women legal minors who cannot make key decisions for themselves.

Rania, a 34-year-old Saudi woman, said, “We are entrusted with raising the next generation but you can’t trust us with ourselves. It doesn’t make any sense.”

Every Saudi woman, regardless of her economic or social class, is adversely affected by guardianship policies.

Adult women must obtain permission from a male guardian to travel, marry, or exit prison. They may be required to provide guardian consent in order to work or access healthcare. Women regularly face difficulty conducting a range of transactions without a male relative, from renting an apartment to filing legal claims.

The impact these restrictive policies have on a woman’s ability to pursue a career or make life decisions varies, but is largely dependent on the good will of her male guardian. In some cases, men use the authority that the male guardianship system grants them to extort female dependents. Guardians have conditioned their consent for women to work or to travel on her paying him large sums of money.

Women’s rights activists in Saudi Arabia have repeatedly called on the government to abolish the male guardianship system, which the government agreed to do in 2009 and again in 2013 after its Universal Periodic Review (UPR) at the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Following both hearings, Saudi Arabia took limited steps to reform certain aspects of the guardianship system. But, these changes remain insufficient, incomplete, and ineffective; today, the guardianship system remains mostly intact.

Until the guardianship system is removed entirely, Saudi Arabia will remain in violation of its human rights obligations and unable to realize its Vision 2030, the country’s “vision for the future,” that declares women—half of the country’s population—to be a “great asset” whose talents will be developed for the good of the country’s society and economy.

Reforms

Saudi Arabia has made a series of limited changes over the last 10 years to ease restrictions on women. Notable examples include allowing women to participate in the country’s limited political space, actively encouraging women to enter the labor market, and taking steps to better respond to domestic violence.

For example, in 2013, then-King Abdullahappointed 30 women to the Shura Council, his highest advisory body. On December 12, 2015, authorities allowed women to participate in municipal council elections, with women voting and running as candidates for the first time in the country’s history. The elections were a significant, symbolic victory for women, particularly as many women had campaigned for this right for more than a decade.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has also issued a range of decisions significantly increasing women’s access to the labor market, as part of a broader economic reform program aimed at decreasing the country’s reliance on oil. These include removing language in the labor law that previously restricted women’s work to certain fields “suitable to their nature,” and no longer requiring that woman have guardian permission to work. Authorities have provided incentives to employers to hire women and earmark certain positions for women and provided thousands of scholarships for women to study in universities abroad.

Saudi Arabia has also taken steps to better respond to violence against women and to provide women with better access to government services. In 2013, it passed a law criminalizing domestic abuse and, in 2016, established a center specifically tasked with receiving and responding to reports of family violence.

Saudi Arabia has also worked to improve women’s access to government services, including enabling women to secure their own ID cards; issuing to divorced and widowed women family cards, which specify familial relationships and are required to conduct a number of bureaucratic tasks; and removing requirements that a woman bring a male relative to identify them in court.

Limitations of Reforms

While the reforms are a step in the right direction, they remain partial and incomplete. The male guardianship system remains largely in place, hindering and in some cases nullifying the efficacy of these reforms.

As Hayat, 44, said, “I don’t believe we can change this in small steps. It is what is happening right now. We need a very brave call from the government to remove this [guardianship] and make it equal.”

While women now serve on the Shura Council and on municipal councils, these victories remain limited and authorities continue to curb women’s ability to participate in public life. Women made up less than 10 percent of the final list of registered voters for the December 15, 2015 elections.

Many women faced barriers linked to the guardianship system when registering to vote, such as a requirement to prove residency in their voting district—a difficult or impossible task for many women whose names are not generally listed on housing deeds or rental agreements—or a requirement to present a family card, often held by a male guardian. In the end, only 21 women were elected to the municipal councils out of 2,106 contested seats. Municipal councils themselves have limited authority and, in January 2016, the government decreed council meetings would be sex segregated—women councilors must participate via video link. Following the announcement, a woman councilor stepped down.

The guardianship system also impacts women’s ability to seek work inside Saudi Arabia and to pursue opportunities abroad that might advance their careers. Specifically, women may not apply for a passport without male guardian approval and require permission to travel outside the country. Women also cannot study abroad on a government scholarship without guardian approval and, while not always enforced, officially require a male relative to accompany them throughout the course of their studies.

Zahra, 25, whose father refused to allow her to study abroad, said, “Whenever someone tells me, ‘You should have a five-year plan,’ I say I can’t. I’ll have a five-year plan and then my dad would disagree. Why have a plan?”

If the Saudi government intends to end discrimination against women as it has promised and to further the reforms it has already begun to undertake, it cannot allow restrictions inherent within the guardianship system to continue. For example, the government does not require guardian permission for women to work, but does not penalize employers who do require this permission. The government does encourage employers to hire women, but requires employers to establish separate office spaces for men and women and to enforce a strict dress code on women, policies which create disincentives to hiring women.

The need for substantial, systemic reform is perhaps starkest with regard to the state’s response to violence against women. Saudi Arabia has taken steps to better respond to abuse, but has done so within the framework of guardianship. The guardianship system allows men to control many aspects of women’s lives and makes it difficult for survivors of family violence to avail themselves of protection or redress mechanisms.

The extreme difficulty of transferring male guardianship from one male to another and the severe inequality in divorce rules make it difficult for women to escape abuse. Men remain women’s guardians, with all the associated levers of control, during court proceedings, and until a divorce is finalized. There is deeply entrenched discrimination within the legal system, and courts recognize legal claims brought by guardians against female dependents that restrict women’s movement or enforce a guardian’s authority over them.

Women who have escaped abuse in shelters may, and in prisons do, require a male relative to agree to their release before they may exit state facilities.

Dr. Heba, a women’s rights activist, explained, “The [authorities] keep a woman in jail… until her legal guardian comes and gets her, even if he is the one who put her in jail.”

Failing to abolish these and other tools available to male guardians to control and extort female dependents will guarantee that women continue to face tremendous obstacles when trying to seek help or flee abuse by violent guardians or simply to pursue paths different than the ones their guardians have determined best.

The Time is Now

Saudi officials often argue that the failure to end discrimination against women is not due to state policy, but due to difficulties in implementation, and that the country must move slowly as the government’s hands are tied by a conservative culture and a powerful clerical establishment’s interpretation of Islamic law.

Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman told the Economist that women’s travel was not entirely restricted, and pointed to social and religious criteria to explain the restrictions that he believed existed. When asked why women’s labor force participation was so low, he said, “The culture of women in Saudi Arabia. The woman herself.”

Saudi Arabia’s imposition of the guardianship system is grounded in the most restrictive interpretation of an ambiguous Quranic verse—an interpretation challenged by dozens of Saudi women, including professors and Islamic feminists, who spoke to Human Rights Watch. Religious scholars also challenge the interpretation, including a former Saudi judge who told Human Rights Watch that the country’s imposition of guardianship is not required by Sharia and the former head of the religious police, also a respected religious scholar, who said Saudi Arabia’s ban on women driving is not mandated by Islamic law in 2013.

The state clearly and directly enforces guardianship requirements in certain areas, including restricting women’s ability to travel and requiring guardian consent for a woman to marry. In other areas, there appear to be no written legal provisions or official decrees explicitly mandating a guardian’s consent or presence, but public officials and private businesses ask women for either without fear of sanction.

Saudi Arabia, which acceded to the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 2000, is legally obligated to end discrimination against women without delay, including by abolishing the male guardianship system. As long as it fails to take steps to eliminate the discriminatory practices of male guardianship and sex segregation, the government is undermining the ability of women to enjoy even the most basic rights.

In April 2016, Saudi Arabia announced Vision 2030, which declares that the government will “continue to develop [women’s] talents, invest in their productive capabilities and enable them to strengthen their future and contribute to the development of our society and economy.” The government cannot achieve this vision if it does not abolish the male guardianship system, which severely restricts women’s ability to participate meaningfully in Saudi society and its economy.

In discussing the role of women in Saudi Arabia and the pace of change, Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman said in his Economist interview, “It just takes time.”

That time is now.

Recommendations

Immediate Recommendations

- Ministry of Interior:

- Abolish ministerial regulations requiring a guardian to apply for or renew a woman’s passport, and for guardian permission for a woman to travel abroad.

- Issue family cards to all women.

- Eliminate any restrictions on female driving, ensuring that women are afforded the same opportunities to drive and acquire a driver’s license as men.

- Issue clear and explicit directives allowing women to be released from prisons and juvenile detention centers without being released to a male guardian.

- Ministry of Labor and Social Development:

- Issue clear and explicit directives to all shelters stating that women may leave the shelter independently without the permission of a male guardian and without a requirement that she be released to a male relative.

- Propose amendments to the Protection from Abuse Law, including to article 1, explicitly stating that no family member has the authority to “discipline” female dependents using violence, that “discipline” is not a legal defense in cases involving family violence, immediately rescinding guardianship from those accused of abuse, immediately rescinding guardianship from those who refuse to agree to a woman’s release from prison or her request to leave a shelter, and amending articles in the law that appear to prioritize family reconciliation over protection of the woman or limit shelter options to cases determined to be sufficiently severe by the ministry.

- Issue clear and explicit directives to all places of employment prohibiting employers from requesting guardian permission from women to work and imposing penalties on any employers that do so.

- Abolish fines and regulations that discriminate between men and women, including those requiring employers to maintain separate office spaces for women and imposing strict dress code requirements specifically on women.

- Ministry of Education:

- Issue and impose sanctions on educational institutions that delay, hinder, or prevent paramedic access to women’s university campuses and schools.

- Issue a directive clearly stating that women may study abroad on government scholarships without a male guardian’s permission or accompanied by a male relative.

- Ministry of Health:

- Issue clear and explicit directives to all hospitals and clinics prohibiting all staff from requesting guardian permission to allow an adult woman to be admitted or receive care of any kind, and establish penalties for institutions that continue to require guardian permission.

General Recommendations

- King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Sa’ud:

- Issue clear and explicit directives to the religious police stating they do not have the authority to impose sex segregation.

- Issue clear and explicit directives to the Ministries of Health, Education, Interior, Justice, and Labor and Social Development prohibiting staff from requesting a guardian’s presence or permission to allow a woman access to any government service.

- Promulgate by royal decree a prohibition on any form of discrimination against women in practice, policy or regulation and the dismantling of the legal guardianship system for adult women, guaranteeing that women are considered to have reached full legal capacity at 18 years of age.

- Task the Social Affairs, Family and Youth Committee in the Shura Council with monitoring the implementation of CEDAW and Saudi laws, royal decrees, and ministerial decisions that advance women’s rights, including decisions that limit a guardian’s authority. Require an annual report on progress be delivered to the king and made public.

- Lift reservations made upon acceding to CEDAW, which violate the object and purpose of the treaty, and sign and ratify the Optional Protocol to CEDAW.

- Ministry of Interior:

- Establish separate units within police stations focused on domestic violence and ensure that all police stations employ female officers.

- Issue guidelines to police on how to deal with domestic violence cases, including penalties for officers who do not allow women to file a complaint, refuse to enter a residence without male approval when abuse is reported, fail to refer cases to the Ministry of Labor and Social Development, or who share case details with a guardian in a manner that violates privacy or may expose a woman to violence.

- Support proposed amendments to the Civil Status Law to allow women to obtain all forms of identification available to men and to register themselves, their marital status, and births and deaths of family members with Civil Status offices.

- Ministry of Justice:

- Ensure women are afforded the same rights as men to file a case and testify in court on all matters, and enforce penalties for court officers who fail to accept a woman’s identification card and allow her to access court without a male relative identifying her.

- Undertake a thorough review and issue guidance to judges prohibiting them from enforcing a guardian’s authority over a woman through the legal system.

- Abolish the right to file legal claims against women based on ‘uquq (parental disobedience), inqiyad (submission to a guardian’s authority), or leaving the marital or guardian’s home. Remove these claims from the ministry’s electronic complaint system.

- Issue a directive to the Board of Grievances to hear cases of discrimination against women by state bodies or officials.

- Support a new family law code that ensures men and women have equal rights in family matters, including establishing 18 as the minimum age of marriage, ensuring all adults have the right to freely enter into marriage, that which parent a child should live with is determined on the basis of the best interests of the child in line with international standards, and that during a marriage and following divorce, parents have equal rights to open bank accounts, enroll in school, make health decisions or travel with children.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews conducted with 61 Saudi individuals, including 54 women and seven men. A Human Rights Watch researcher conducted eight interviews in person with individuals based outside Saudi Arabia and 43 interviews by phone, Skype, or other electronic communication between September 2015 and June 2016.

Interviews included Saudi women from a range of professional and socioeconomic backgrounds. Most individuals were from Jeddah or Riyadh, but some individuals were from the Eastern Province (Dammam, Al-Khobar, Qatif, and Dhahran), central Saudi Arabia (Riyadh, Al-Kharj and Shaqra), southern Saudi Arabia (al-Abha), and the Hijaz (Jeddah and Mecca). Three individuals from the Shia minority community and one LGBT woman were interviewed. Human Rights Watch developed recommendations following discussions with 12 Saudi women’s rights activists. The report also includes research from Human Rights Watch press releases published between 2010 and 2015. Human Rights Watch published another report on the male guardianship system in Saudi Arabia in 2008.[1]

All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, the ways in which the data would be used and given assurances of anonymity. This report uses pseudonyms for all interviewees and withholds other identifying information to protect their privacy and their security. Saudi terrorism regulations criminalize harming the reputation of Saudi Arabia, and the government has imprisoned human rights activists who have shared information with foreign organizations. None of the interviewees received monetary or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. All interviews were conducted in English or Arabic.

Human Rights Watch was unable to conduct fact-finding inside Saudi Arabia for this report, despite sending official visa requests to the Saudi government in October 2015. The government has not issued official visas to Human Rights Watch staff since 2008. In May 2016, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Ministries of Health, Interior, Justice, Labor and Social Development, and Education requesting meetings to discuss the report findings prior to publication. Human Rights Watch received no response.

I. The Religious Establishment

The role and rights of women in Saudi Arabia are disproportionately affected by the views of the Wahhabi religious establishment, which largely opposes the empowerment of women and follows what is often considered the most restrictive interpretation of Islam.[2]

Originating, developing, and spreading from Najd in central Arabia, it does not—according to numerous scholars—reflect the true diversity of views within the country regarding the role of women or the state’s role in enforcing Islamic law.[3]

Saudi Arabia applies this interpretation of Sharia as the law of the land, elevates the Quran and the Prophet’s traditions to the status of a constitution, and has institutionalized the religious establishment and its perceptions of women into governance structures.[4]

The religious establishment largely controls education, the all-male judiciary, and policing of “public morality” through the religious police, or the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, informally known as the Hai’a.[5]

The Council of Senior Religious Scholars, the highest religious body that acts as a forum for regular consultation with the king, who created the council in 1971, has consistently promoted opinions that restrict women’s rights.[6] The General Presidency for Scholarly Research and ‘Ifta, the official institution entrusted with issuing Islamic legal opinions, has also consistently limited women’s ability to make independent decisions in its fatwas.[7]

The General Presidency’s website lists dozens of fatwas on women, many of which reinforce men’s authority over women and restrict their ability to move, work, and study. For example, the General Presidency stated that women cannot serve in leadership positions over men because of their “deficient reasoning and rationality, in addition to their passion that prevails over their thinking.”[8]

In another ruling, it stated, “A woman should not leave her house, except with her husband’s permission.” If he does, “She should go out unadorned so that she does not attract men’s attention.… Her husband can prevent her from going out if she insists on displaying her beauty.”[9]

Islamic scholars who support the imposition of male guardianship do so based on an ambiguous verse in the Quran. The verse states, “Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because God has given the one more [strength] than the other, and because they support them from their means” (Quran 4:34).[10]

Other Islamic legal experts have argued that male guardianship as interpreted by Saudi Arabia misinterprets fundamental Quranic precepts and that male scholars have elevated guardianship over Quranic concepts like equality and respect between the sexes.[11]

Professors, Islamic feminists and a former Saudi judge also told Human Rights Watch that the way in which Saudi Arabia imposes guardianship over women is not required by Islamic law. Sura, 62, a retired university lecturer, said: “We are living in a male society; that is for sure. Religion is being interpreted through a male perspective for the sake of the man.”[12] The former judge explained:

According to the Sharia, there is no need for any guardian [for women], except when she travels in a risky situation.… All the Sharia schools consider that women after adulthood … should be considered as an independent human being…. royal orders and ministry orders talking about the permission of the guardian against the women … aren’t rooted in Sharia law.[13]

The state itself has actively imposed restrictions on women or failed to take measures to halt discriminatory cultural or social practices. As Madawi Al-Rasheed, a prominent Saudi academic, said: “The interaction between the state, religious nationalism, and social and cultural forms of patriarchy” has led to the continued restriction of women’s rights in Saudi Arabia. [14]

Respected Saudi commentators and prominent women’s rights activists have argued and continue to argue forcefully that women in Saudi Arabia are not only ready for the guardianship system to be reformed and ultimately abolished, but that these reforms are necessary in order to provide women the respect, and the rights, that they deserve.[15]

II. The Male Guardianship System

My son is my guardian, believe it or not, and this is really humiliating... My own son, the one I delivered, the one I raised, he is my guardian.

—Sura, 62, retired university lecturer, December 14, 2015

Every Saudi woman, regardless of her age, is under the authority of a male relative, her wali al-amr, or legal guardian. A woman’s legal guardian has the authority to make a range of critical decisions on her behalf.

A woman’s other male relatives are also granted authority over her, although to a lesser extent than her legal guardian. A mahram, a male relative who it would be unacceptable to marry, has the authority to accompany a woman on a government scholarship abroad or to receive her when she leaves a domestic violence shelter. Courts or other government services may ask a woman to be accompanied by a mu’arif, a male relative who can verify a woman’s identity while she is wearing a face veil. In practice, individuals and government officials may ask women to be accompanied by a male relative in order for her to conduct a range of important tasks, from co-signing a lease to filing a police complaint. A woman’s legal guardian can also serve as a mahram or mu’arif.

In this report, the terms “male guardianship system” and “guardianship rules” refer to the panoply of formal and informal barriers women in Saudi Arabia face when attempting to make decisions or take action without the presence or consent of a male relative.

Many aspects of the guardianship system are not codified in law but stem from informal practice—both by private actors and government officials. As such, women’s experience of guardianship restrictions varies widely based on a range of factors such as socioeconomic status, education level, and place of residence.

Zeina, a Saudi businesswoman in her 40s, told Human Rights Watch that women's experience with guardianship is closely related to social class. In her experience, wealthier families, including male guardians, tend to be more open to women working and traveling, whereas families in lower socioeconomic classes are generally more conservative. Wealthier women, she explained, can also afford to pay some of the costs associated with women’s rights restrictions, like male driver’s fees. As she said, “As you go up the social ladder it becomes easy; as you go down it becomes almost impossible.”[16]

A woman’s experience in Saudi Arabia remains dependent on the good will of her male guardian. Dozens of women told Human Rights Watch they were fortunate to have supportive male guardians who allowed them to work, study, travel and marry, but said that they should not require permission to make these choices in the first place.

Dr. Zahra, who treats domestic violence cases in the hospital where she works, said that her husband had always been kind to her but “in the back of [your] brain, [you know], if he wants to be mean, he could be mean. And the law would protect him. I don’t want to live my life with this in the back of my mind... I want my rights.”[17]

Transferring Guardianship

Initially, a woman is under the legal guardianship of her father. When she marries, her husband becomes her new guardian. When a guardian dies or a woman divorces, a new guardian is appointed, generally, the next oldest mahram.[18] Guardianship authority may revert to a woman’s younger brother or son if she does not have older male relatives.[19] As Mara explained, “I am divorced, so I resort back to my brothers. It happens immediately. If there is a father, I go back to my father. It is like I am property.”[20]

Women may transfer legal guardianship to another male relative, but it is an extremely difficult legal process. Four activists told Human Rights Watch that it is very difficult to transfer guardianship outside of cases of severe abuse or if a woman can otherwise prove the guardian is incapable, for example due to old age. Even then, it can only be done through a court order and can be difficult to establish the requisite level of proof.[21] Aisha, a woman’s rights activist, said she was aware of some cases where women successfully transferred guardianship, but that many women were unsuccessful.[22]

|

“As Long As He is Not Beating You, He Can Do Whatever He Wants” Zahra, 25, told Human Rights Watch that her father beat her and her sister when they were children. When Zahra was 12, her father beat her so severely that she temporarily lost her vision. She thought she was going blind. Zahra’s mother took her to the hospital. The doctor told her she was lucky the damage was not permanent. Zahra’s parents divorced. The girls lived with their mother, but their father remained their legal guardian and threatened to force them to live with him if they disobeyed him. In 2011, the government awarded Zahra’s sister a scholarship to study abroad, but Zahra’s father refused to let her go. Zahra also wanted to pursue a master’s degree abroad in a field not available in Saudi Arabia. Her father refused. She said, “I am lost in my career because that was my goal. Whenever someone tells me, ‘You should have a five-year plan,’ I say I can’t. I’ll have a five-year plan and then my dad would disagree. Why have a plan?” Zahra and her sister sought help from a charity, but the organization told them that denial of travel or education abroad was not a sufficient basis to transfer guardianship. According to Zahra, she and her sister told the charity that their father physically abused them when they were children, but the organization said it could not intervene unless the physical abuse was ongoing. Zahra’s sister, who was one of the top students in her university, fell into depression, pulled out of school and remained at home for a year. In 2015, Zahra, who now needed to travel for work, called five lawyers to ask for help transferring guardianship away from her father. Each lawyer told her that denial of travel or forcing her to quit her job was not a sufficient basis for transferring guardianship. According to Zahra, the lawyers told her, “As long as he is not beating you, he can do whatever he wants.” When asked if she felt being unable to travel held her back in her career, Zahra said, “Definitely.” Her father remains her guardian.[23] |

Human Rights Watch spoke with women who said their friends or family members sought to marry to escape strict, conservative, or abusive fathers and brothers.[24] Tala, in her late 20s, told Human Rights Watch:

The guardianship system is always a nightmare. I don’t want to get married because I don’t want a stranger to control me… Basically, it is slavery. My sister married this guy to get away from my brother… If I have to go back to Saudi, I am going to be just like the other Saudi girls and get married to get away from my brother.”[25]

International Law and Guardianship

The practice of male guardianship in its many forms impairs and in some cases nullifies women’s exercise of a host of human rights, violating the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which Saudi Arabia ratified in 2000, and other human rights conventions. CEDAW obliges Saudi Arabia “to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating discrimination against women.”[26] Numerous other treaties and treaty bodies acknowledge women’s equal right to men to travel, work, study, access health care, and marry without discrimination.

CEDAW explicitly acknowledges social and cultural norms as the source of many women’s rights abuses and obliges governments to take appropriate measures to address such abuses.[27] In 2008, the UN Committee on Discrimination Against Women expressed concern that the concept of male guardianship over women in Saudi Arabia “severely limits women’s exercise of their rights under the Convention” and called on Saudi Arabia to “take immediate steps to end the practice of male guardianship over women.”[28]

Saudi Arabia has failed both to end state practice premised on the inferiority of women and to take sufficient measures to tackle discriminatory customary practices. The UN Committee on Discrimination Against Women and the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child have called on states to pursue targeted policies “of an immediate nature” to combat traditional harmful practices and noted that they “cannot justify any delay on any grounds, including cultural and religious grounds.” Moreover, the committees noted that states are:

[O]bliged to take all appropriate measures…. to modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other practices that are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women.[29]

In 2009 and again in 2013, Saudi Arabia agreed to abolish the male guardianship system and all discrimination against women following its universal periodic review at the UN Human Rights Council.[30]

Since making these promises, Saudi Arabia has taken steps to lessen guardians’ control over women, including, for example by no longer requiring women to provide guardian permission to work or to bring a male relative to identify them in court, but has failed to abolish the system or adequately combat deeply entrenched discrimination, failing in its duty “to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating discrimination against women.”[31]

III. Restricting Freedom of Movement

It is very hard to say you live, you just survive... The simple freedom of opening your door and going out for a walk… I have to call a driver to get my coffee. What if I want to walk in peace and get my coffee and come back?

—Rania, 34-year-old Saudi woman, November 17, 2015

No country restricts the movement of its female population more than Saudi Arabia. Women cannot apply for a passport or travel outside the country without guardian approval and women are barred from driving. In practice, some women are prevented from leaving their homes without their guardian’s permission and guardians can bring legal claims requesting that judges order a female dependent to return to the family home.

Restrictions imposed on women’s freedom of movement violate article 15(4) of CEDAW.[32] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights also provides: “Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state… [and] to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.”[33]

These restrictions also inhibit the effectiveness of other reforms Saudi Arabia has undertaken, such as in the labor sector, by making it more difficult for enterprising women to attend business conferences or pursue academic studies outside the country, or to travel to and from work inside the country. As Maysa, a Saudi woman who struggled to convince her father to allow her to work and study abroad, said “Freedom of movement … is one of the basic human rights and that is what I really want to change.”[34]

The ability to control a woman’s movement is a powerful tool for male guardians to exploit female dependents. Guardians have conditioned consent for a woman to travel on payment of money or dropping a court case against them.

Restrictions on Travel Abroad

Saudi authorities deny women the right to acquire a passport without a guardian’s permission. According to Ministry of Interior regulations, a guardian must apply for and collect a passport for women and minors.[35] The government’s electronic portal requires a male guardian to make the actual application for or renewal of a woman’s passport.[36]

Reema, 36, told Human Rights Watch she went to renew her passport when she was separated from her husband. The women’s section refused her request. Reema offered to have her father sign the paperwork, but officials insisted her husband, her guardian, must sign. Because she was unable to renew her passport, Reema had to cancel a number of workshops and meetings abroad that she had planned to attend.[37]

In addition to requiring a guardian’s approval to receive or renew a passport, the Ministry of Interior prohibits Saudi women from traveling outside the country without the approval of their male guardian.[38] One woman said that her 64-year-old widowed mother had to seek her 27-year-old son’s permission to travel.[39]

Khadija, 42, a former journalist, said, “My dad passed away, [so for] my mom and myself, my brother is our guardian. It is really ridiculous. If she wants to travel, she needs the permission of her son. Why? Come on, why would an elderly woman need the permission of her son or even grandson to travel or to do anything?”[40]

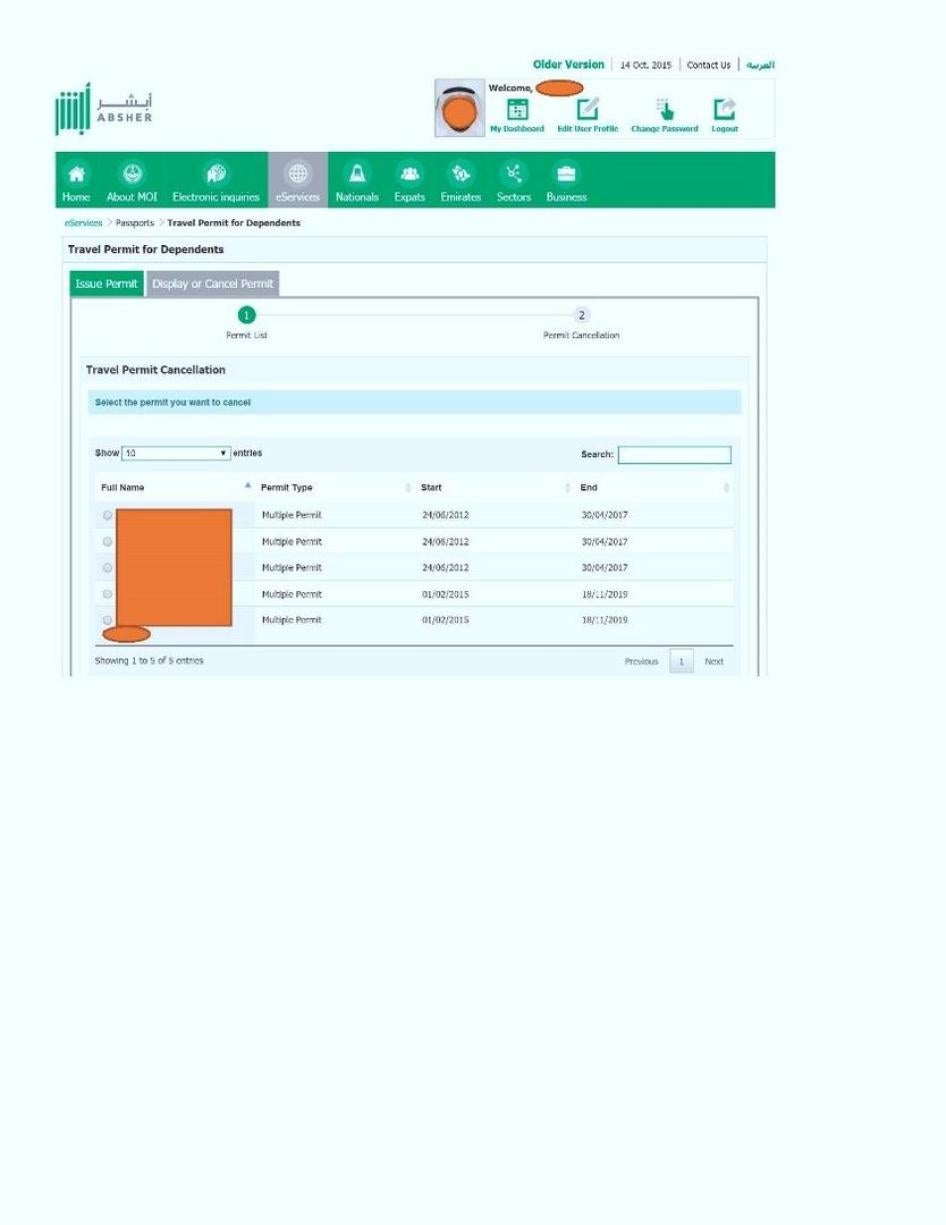

In 2011, the Ministry of Interior set up an electronic portal, “Absher,” where male guardians can issue passports to female dependents and approve their travel.[41] The site allows guardians to provide permission for a single trip, for multiple trips or until the passport expires.[42] Khadija told Human Rights Watch:

This is sort of progress in a way where the system allows for the guardian to give an open permission, rather than for every trip… but that is not the point. I am old enough to travel when I want to travel. I don’t need someone else’s permission.[43]

After Saudi authorities launched “Absher,” they began to notify male guardians about the entry and exit of their female dependents to and from Saudi Arabia via an automatic text message. In 2012, women began to vocally critique the text message alerts on Twitter. By early 2014, the authorities announced that they suspended text notifications.[44] Maysa, 25, said, “You would think the government would use technology to move forward but instead they are moving backwards.”[45]

Human Rights Watch spoke with multiple women whose guardians had threatened to or in fact refused to allow them to travel abroad. Rania, 34, came back to Saudi Arabia to visit her family after living abroad for many years. When she sought to leave, her brothers, acting as her guardians, refused to renew her travel permission. Rania said she had to resort to some drastic measures, including refusing food, until her brothers finally relented and allowed her to travel again.[46] Layla, also in her 30s, told Human Rights Watch that her father used to take her travel permission slip away after fights.[47]

|

Tala and Travel Permission Tala, in her late 20s, recently completed a Master’s degree outside Saudi Arabia. Tala told Human Rights Watch that she wanted to return to visit her family but had not done so for more than three years over threats from male family members that they would prevent future travel. For example, after seeing some of Tala’s posts on Twitter where she questioned her religion in 2012, her brother threatened to rip up her passport if she came back to Saudi Arabia. Tala’s father also threatened to call the Saudi embassy, ask them to force her to come back, and to not renew her passport or her travel permission once she had. Neither Tala’s father nor brother followed through on their threats, but Tala, whose passport was set to expire in a few months at time of writing, said she did not know what to do. She told Human Rights Watch, “I can’t go back because I am constantly afraid that my brother and my dad will prevent me from coming back [abroad]. They have all the authority to do so.”[48] |

Men occasionally extort female dependents for travel permission. Zeina, a successful businesswoman, told Human Rights Watch that her friend who works as an instructor at a university abroad “still struggles with the fact that her guardianship is completely controlled by her father with whom she has zero connection.” Zeina said her friend had to hire a lawyer to negotiate with her father, who was seeking financial compensation in return for granting his daughter travel permission.[49]

Requiring guardian permission for women to travel makes it difficult for women exposed to family violence to escape abuse. Human Rights Watch spoke with women who felt their only safe option was to leave the country after male family members abused and threatened them, but who were unable to convince their fathers to allow them to travel.[50]

Guardians revoking or withholding travel permission may also seriously hamper a woman’s professional advancement. Over eight years, the guardians of at least two of Dr. Heba’s colleagues prevented them from pursuing advanced degrees abroad.[51] Maysa, 25, said that when she wanted to complete an advanced degree abroad, her parents initially refused. Regardless, she applied to a foreign university. Following her acceptance, her father continuously changed his mind—agreeing to let her go and then revoking his consent—until two days before the flight. As Maysa said, “Even though he is educated, he thinks it is one of his rights to not allow his daughter to continue her education.” She went on to explain, “My other friends are hopeless. I know that they do want to go and explore the world, but for them they know there is no way out unless they get married.” She noted that not all of her friends’ new husbands met their expectations of greater freedoms.[52]

Mahram for Scholarships Abroad

The government has paid for thousands of women’s education abroad through the King Abdullah Scholarship Program, instituted in 2005.[53] According to Ministry of Education statistics, 62.3 percent of program participants were women between 2009 and 2014.[54]

Multiple women told Human Rights Watch that the scholarship program had been incredibly helpful in letting them pursue opportunities for higher education.[55] Hanan, 36, an architect, said that education is the weapon women need to realize all of their rights, noting, “If King Abdullah did not do that, I don’t know what the situation would be now… This is the most beneficial thing the government ever spent their money on.”[56]

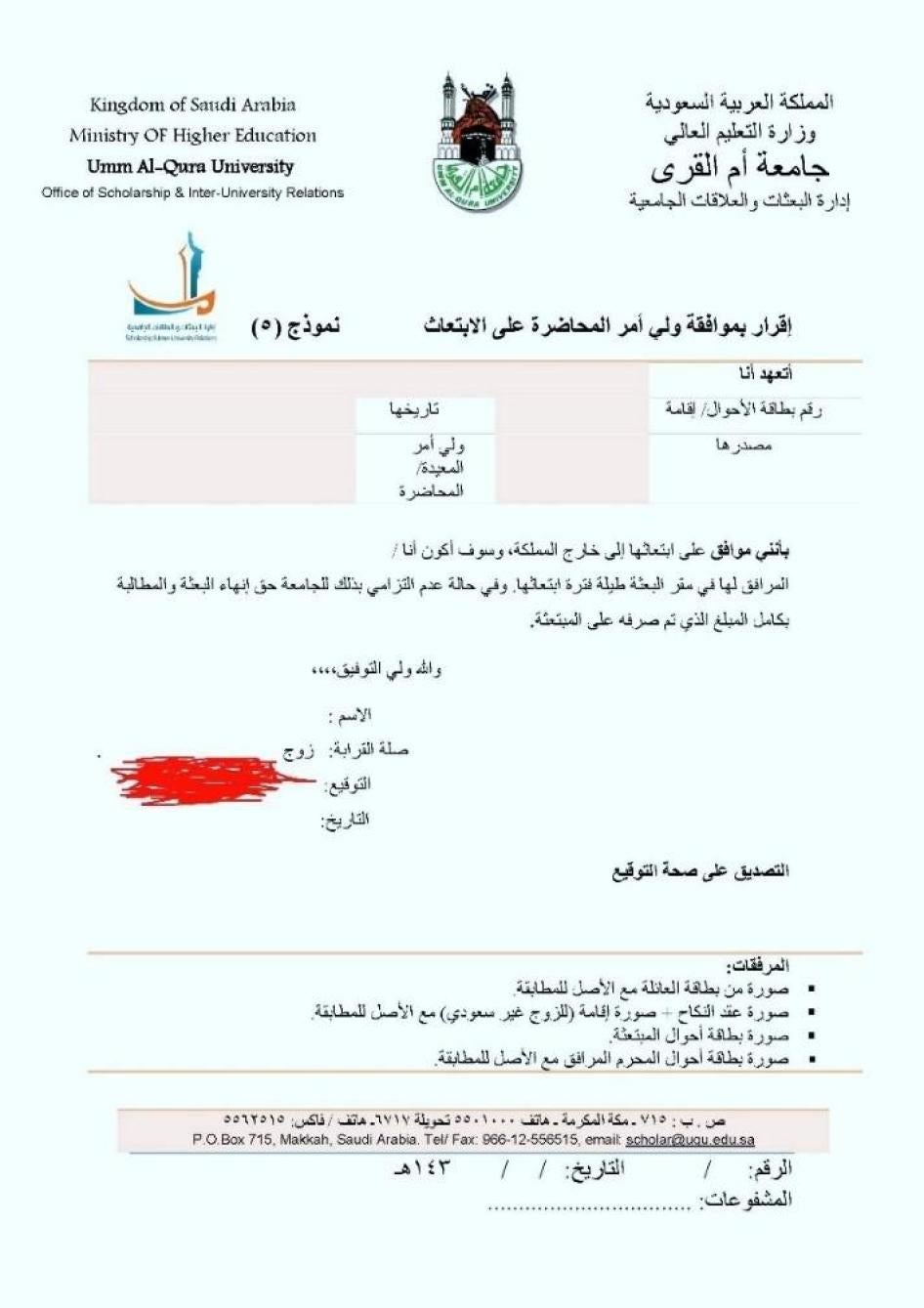

The scholarships come with requirements. The Ministry of Education requires that a woman’s male guardian sign a form consenting to allow her to study outside the country.[57] The ministry also requires that a mahram (an unmarriageable male relative who may or may not also be the woman’s official guardian) accompany a woman for the duration of her studies. The government provides living expenses for the mahram.[58]

Zayn and Nisreen, 24 and 25, explained that if a woman’s guardian cannot accompany her, he must legally transfer authority to another male relative to serve as a mahram. Nisreen and Zayn said they had been fortunate that their brothers could travel with them as mahrams, but that they knew smart, hard-working women unable to study on a scholarship because of the mahram requirement.[59]

Najma, for example, was awarded a government scholarship and worked hard to convince her father to allow her to study abroad. He finally agreed. She left the country, made friends, and fell in love. She visited her family in Saudi Arabia after a few years. Najma’s mother found out she was in a relationship and took away her passport and her national ID card. Najma believed her father revoked her travel permission, and felt she had no means of legal recourse to recover her passport or travel. Najma is unable to finish her degree.[60]

While the mahram requirements are not always strictly enforced, officially requiring a mahram and guardian consent are onerous requirements for women hoping to pursue further education abroad, especially where men may use it for extortion.[61]

Dr. Heba told Human Rights Watch that her divorced friend had three children, all girls. After the girls received scholarships to study abroad, the friend’s ex-husband forced her to pay him thousands of Saudi riyals to accompany his daughters abroad and to serve as their mahram. Dr. Heba said her friend had no choice, as the girls’ father was the only one that could give them the permission to travel and to accept the scholarship.[62]

A guardian’s refusal to provide permission can hamper a women’s professional advancement. Khadija, 42, said that one of her employees hoped to go abroad to continue her studies. After the woman's father died, her brother became her guardian. He refused to allow his sister to follow through on her plans, forcing her to stay in the country.[63]

Restrictions on Domestic Movement

Formally, women do not require guardian permission to travel anywhere inside Saudi Arabia, including flying between cities.[64] Informally, women may require their guardian’s permission to leave the home.

A fatwa issued by the General Presidency for Scholarly Research and ‘Ifta, a state institution tasked with issuing Islamic legal opinions, on women’s work states, “[A] woman should not leave her house, except with her husband’s permission.”[65] Activists told Human Rights Watch that it is very easy for male guardians to force women to remain indoors and prevent them from leaving home without their permission.[66]

Courts provide support for this practice, occasionally upholding a guardian’s right to obedience from his female dependents, including the obligation to abide by his decisions regarding their movement. For example, in November 2015, a Saudi appeals court upheld a ruling of 30 lashes for a man for slapping his wife and spitting on her. According to Arab News, the husband said he hit his wife because she had gone out of the house several times without seeking his permission. The judge reportedly ordered the wife to abide by her husband's request not to leave the house without his permission.[67]

The Ministry of Justice explicitly bolsters a guardian’s authority to deny women freedom of movement. The ministry’s website contains a list of complaints that can be filed through its electronic complaints system, including two which request that a judge order the return of a woman to a mahram or a wife to the marital home.[68]

Some universities also restrict women’s movement. Female students living in university dormitories may be prohibited by school authorities from leaving campus even in cases of illness except with a legal guardian.[69]

Amira, 42, told Human Rights Watch that her daughter, 22, studied in a Riyadh college and lived in a dormitory. The college required her daughter’s legal guardian to sign her out of the dormitory. Amira’s husband had to go to court to obtain a legal document authorizing Amira and their son to visit and allow his daughter to exit the university compound with them. As Amira’s home is four hours away from Riyadh, her daughter is forced to sit inside the compound for months at a time, until either her father or someone legally authorized takes her out. She said it is “like a prison.” The policy sometimes prevents Amira’s daughter from completing simple tasks, like fixing a broken laptop.[70]

Driving

Women driving leads to many evils and negative consequences….

—Fatwa banning driving

Saudi Arabia remains the only country in the world that prohibits women from driving. The government’s restrictions on driving combined with limited affordable and accessible public transportation options prevent Saudi women from fully participating in public life.[71]

Saudi Arabia had a customary ban on women driving until 1990, when it became official policy.[72] On November 6, 1990, 47 women drove in a convoy in Riyadh in protest. The traffic police stopped the protesters, took them into custody, and released them only after their male guardians signed statements that the women would not attempt to drive again.

Sho"rtl"y after, the late Shaikh 'Abd al-‘Aziz bin Baz, then-chairman of the Council of Senior Religious Scholars, issued a fatwa prohibiting driving. The fatwa stated, “Women driving leads to many evils and negative consequences… [including] mixing with men without her being on her guard… Sharia prohibits all things that lead to vice. Women’s driving is one of the things that leads to that. This is well-known.”[73]

The fatwa on the driving ban cited the goal of preventing women from committing acts of khilwa (mixing with unrelated members of the opposite sex). Yet, because of the ban, women must take taxis driven by men or hire male drivers, often foreign nationals.[74] Then-Minister of Interior Prince Nayef officially banned women’s driving by decree on the basis of this fatwa.[75] Women who have driven in the country have subsequently been arrested.[76]

Women have continued to campaign for the right to drive. In 2011, dozens of women filmed themselves driving and posted the videos to social media as part of a campaign entitled “women2drive.” Traffic police stopped many women and made their male guardians sign pledges that they would not allow the women to drive again.[77]

Saudi authorities have issued conflicting statements regarding whether women would be allowed to drive. In 2005, then-King Abdullah said in an interview that he believed “the day will come when women drive.”[78] In September 2013, the head of the Hai’astated that Islamic law does not forbid women from driving.[79] A month later, Saudi women launched the October 26 driving campaign, including publishing videos of women driving and Saudi men giving the thumbs-up sign to show their support.[80] In response to the campaign, on October 22, 2013, more than 100 clerics visitedthe Royal Court, the office of the king, to protest “the conspiracy of women driving.”[81] The following day, a Ministry of Interior spokesperson issued a statement saying that laws would be enforced on October 26.[82]

IV. Violence against Women

I would rather you kill me than give the man who abuses me control over my life.

—Zahra, 25-year-old Saudi woman, April 7, 2016

As in many countries across the globe, many women in Saudi Arabia are regularly and repeatedly subjected to violence.[83] This violence often occurs in the family.

Over a one-year period ending October 13, 2015, the Ministry of Labor and Social Development reported that it encountered 8,016 cases of physical and psychological abuse in Saudi Arabia, most involving violence between spouses.[84] The ministry recorded 961 cases of domestic violence in one year in one major city alone, with most cases involving women and children being denied their basic rights to education, health care, or personal identification documents.[85]

Such forms of violence are clearly linked to abuse of the guardianship system. It is likely the vast majority of cases go unreported, given the isolation of victims and difficulty of reporting and seeking redress.

Domestic violence prevents women from exercising a host of rights, including the right not to be subject to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, to security of the person, and, in extreme cases, to life.[86]

Saudi authorities have increasingly recognized violence against women as a public policy issue. In 2005, the government created the National Family Safety Program, which focuses on ensuring that domestic violence survivors have access to shelters and protection mechanisms. In 2013, the King Khalid Foundation, a charity set up in 2001 by family members of the late king, launched a high-profilemedia campaign claiming that “the phenomenon of battered women” in Saudi Arabia is “much greater than is apparent on the surface.” The same year, the king ratified a law criminalizing domestic abuse.[87] While women told Human Rights Watch the law was a significant step forward, they also critiqued it for being overly general, not robustly enforced, and not adequately defining solutions or even options for women abused by their guardians.[88]

The male guardianship system creates an environment ripe for abuse. Saudi women have repeatedly called for the immediate removal of authority from any guardian who abuses a female family member. Aisha, who has many years of experience helping domestic violence survivors, said, “This is what we called [for]: To protect [a woman] from [her] abuser, [we] need to give her the right to protect herself.”[89] As one Saudi commentator wrote, “The definition of what is allowed [to guardians] and what is not remains vague … encourag[ing] perpetrators to indulge in physical and mental abuse of women.”[90]

Guardianship makes it incredibly difficult for victims of violence to seek protection or obtain legal redress for abuse. The near impossibility of transferring guardianship away from abusive relatives can condemn women to a life of violence.[91] Women occasionally struggle to report an incident to the police or access social services or the courts without a male relative.[92]

According to multiple domestic violence specialists and women’s rights activists, Ministry of Labor and Social Development officials often prefer to reconcile female victims of violence with her family to other options. Prisons, juvenile detention centers, and shelters may only allow women to exit into the care of a male relative.[93] Imprisoned women whose families refuse to release them are forced to remain in prison or in shelters until they reconcile with their families or obtain a new guardian, occasionally only after arranged marriages.[94]

When legal guardianship impedes redress for victims of violence, Saudi Arabia is failing to act with due diligence to prevent, investigate, and punish violence against women, putting women’s health and lives in jeopardy. The UN Committee on Discrimination Against Women urged states to ensure that, “in both public and family life, women will be free of the gender-based violence that so seriously impedes their rights and freedoms as individuals.”[95]

Domestic Violence Legislation

On August 26, 2013, the Council of Ministers approved the Protection from Abuse law, which then-King Abdullah ratified.[96] In 2014, the Ministry of Labor and Social Development issued implementing regulations, providing further guidance on how agencies should enforce the law.[97]

Prior to adoption of this law, Saudi criminal justice authorities had no written legal guidelines to treat domestic abuse as criminal behavior. In the absence of a written penal code, judges rely solely on their individual interpretations of uncodified Sharia to determine whether certain actions are defined as criminal.

The Protection from Abuse law defines abuse as, “Any form of exploitation or physical, psychological, or sexual ill-treatment, or threat thereof, perpetrated by one person against another which exceeds the bounds of the guardianship…”.[98]

The law sets the penalty for domestic abuse at between one month and one year in prison and a fine of between 5,000 (US$1333) and 50,000 (US$13,330) riyals unless Sharia provides for a harsher sentence.[99]

The law defines abuse as physical, psychological, or sexual abuse, but does not explicitly state that marital rape is a crime.[100] While the law and the implementing regulations clearly state a guardian may be guilty of abuse, the definition of abuse condones some harm by stating that abuse is only that which “exceed the bounds of the guardianship.”[101] It does not clarify what actions would be permissible within the bounds of guardianship and what would exceed it. The law also does not explicitly include economic abuse as one of the elements of domestic abuse as required under international standards.[102]

Failing to clearly define the bounds of guardianship is particularly problematic in Saudi Arabia, where male relatives can bring legal claims against “disobedient” female dependents. Parents may bring legal claims against their children for ‘uquq (parental disobedience), guardians may bring claims for inqiyad (asserting their right for dependents, including adult women, to submit to their authority), men can bring claims ordering their wives be returned to the marital home, and a mahram (male unmarriageable relative) can request his female relative be returned to him.[103]

Maysa, a law graduate, said that punishments for women convicted of disobedience can range from being sent home to imprisonment.[104] These claims, including ‘uquq and inqiyad, are included on the list of complaints that can be filed through the Ministry of Justice’s electronic complaints system.[105]

Women told Human Rights Watch that courts and other authorities believe guardians have the right to “discipline” their dependents. Maysa, who studied law, told Human Rights Watch that the definition of what constitutes acceptable discipline in court varies based on which judge is interpreting a case. As she put it, “There is no limit to what a guardian can do, [although] he probably can’t kill her.”[106]

Dr. Abeer, a medical professional who specializes in domestic violence, told Human Rights Watch that many in Saudi Arabia, including some social workers, believe guardians have the right to use physical violence to discipline women and children. According to her, the definition of abuse as currently codified maintains the right of the guardian to do, “basically, whatever they want.” Fortunately, she said that in her experience judges have not been interpreting the law this way and have instead increasingly recognized violence by guardians as domestic abuse.[107]

Difficulties Reporting Abuse

Since the adoption of the Protection from Abuse Law of 2013, the government has facilitated reporting of abuse. The law requires individuals, including public servants, to report abuseand gives the police and Ministry of Labor and Social Development the authority to respond to reports of abuse.[108] The implementing regulations specify that guardian consent is not required to accept or respond to reports of abuse.[109]

In 2016, the Ministry of Labor and Social Development launched an all-female staffed center in Riyadh to receive reports of domestic abuse 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The center, which received 1,890 calls within the first three days of operation, refers cases of domestic abuse to protection teams across the country or, in severe cases, to the police.[110]

Despite these steps forward, women still struggle to report abuse, particularly with the police. While Human Rights Watch spoke with women who had filed complaints with the police without a male relative, others said police had turned them away or they felt uncomfortable going to a police station without a male relative accompanying them.[111]

The prevailing environment of sex segregation makes women hesitant to walk into a police station. Almost all police officers are male, according to a women’s rights activist.[112] She said employing female police officers, especially to handle domestic violence cases, would be a “fantastic” improvement.[113]

Police officers do not require a guardian’s permission to hear a complaint as a matter of law, but some officers do ask women to file a complaint with or through a guardian or another male relative. According to four women with significant experience handling domestic violence cases, police occasionally call or send women back to their guardians, even when the woman is attempting to report abuse.[114] Sana, a woman’s rights activist, told Human Rights Watch that the police are far more likely to intervene in an abuse case if a woman’s male relatives involve themselves and support her claim.[115]

A Saudi commentator reported in 2013 that an abused woman who had been locked in a bathroom and urinated on by her husband sought help from the police. According to the writer, the police would not accept her complaint outside the presence of a male guardian.[116] Mara, one of the abuse specialists, said, “In [the] back of [the] woman’s mind, they know they have to have a [male relative] with them in police stations.”[117]

The Protection from Abuse Law provides an important measure: The Ministry of Labor and Social Development may, in a case of severe abuse, make an “emergency intervention or enter a place where abuse has taken place,” including without guardian permission.

Dr. Zahra said that a social worker with whom she works reported that the ministry had done so in a number of cases in her province.[118] In other provinces, however, the ministry and police had not been as responsive. Farah, a child protection specialist, told Human Rights Watch that in cases she has observed, authorities often said they could not enter a house without guardian permission or special permission from a local authority.[119] Amira, 42, told Human Rights Watch about an instance in 2015 when the police refused to enter a woman’s house without her husband’s permission after she reported his abuse.[120]

The law also provides that in cases where abuse is “serious,” the ministry may move a perpetrator out of the home.[121] Two women’s rights activists told Human Rights Watch that police will now place perpetrators in jail if a woman has been visibly beaten or has a medical record indicating abuse.[122]

Sowsan, another abuse specialist, told Human Rights Watch of a 2014 case in which a woman reported her husband, who had severely choked her, to the police. The police arrested the husband, but then called the woman and told her that her husband would not do it again and that she should come to provide bail and release him. Sowsan explained that police often pressure women to forgive their husbands. She said, “Women don’t leave their home unless facing death, so you can imagine the consequences.”[123]

Individuals who attempt to report abuse or provide help to women subject to abuse may find themselves prosecuted. In 2013, a Saudi court convicted two women’s rights activists for “inciting a woman against her husband,” sentencing them to 10 months in prison and two-year travel bans. They had been trying to help a woman who claimed her husband locked her in her house and denied her adequate food and water.[124]

Saudi women and migrant domestic workers who report abuse, including rape, sometimes face counter accusations, leaving them open to criminal prosecution. Women may be charged with moral crimes, like khilwa (mixing with unrelated members of the opposite sex), or with fleeing from their homes.[125]

The male guardianship system, as well as the criminalization of pre-marital consensual relationships between men and women and of “parental disobedience,” can trap women in domestic violence situations. Intisar, for instance, told Human Rights Watch that when her mother found out she was pregnant, she forced Intisar to have an abortion. As Intisar said, “I had no other choice… If my dad found out or one of my brothers, I’ll be killed.” Intisar said her mother also confined her to the house and threatened to send her to jail. Intisar felt she had no safe options, noting that the authorities, including the police and the court system, would side with her parents. Her mother had previously threatened to bring “disobedience” claims against her and family members had beaten her during arguments. Fearing for her safety, Intisar wants to leave the country, but has no means to travel without her father’s consent.[126]

According to three abuse specialists, the Protection from Abuse Law has made judges more responsive to abuse claims. Dr. Abeer, a psychologist who has worked on abuse cases for more than 15 years, said that individual judges have increasingly accepted psychological reports, testimony and expert opinions in custody and domestic violence cases following the implementation of the law.[127] Dr. Zahra told Human Rights Watch that she has seen abuse cases proceed more quickly and women increasingly report to hospitals to receive medical reports of physical abuse. However, she said judges still maintain vast individual discretion and women would benefit from a clearer law.[128]

Prioritizing Reconciliation over Protection

Under the Protection from Abuse Law, authorities can, in cases of abuse, institute protection measures such as ensuring victims receive health care, taking steps to prevent recurrence of abuse, summoning and obliging offending parties to sign pledges, sending victims to shelters, and forcing offenders to undergo psychological treatment or rehabilitation.[129]

Even after the promulgation of the 2013 law, the authorities appear to prioritize reconciliation of the family over the safety of the woman. Basma, a woman’s rights activist, told Human Rights Watch that women are hesitant to report abuse, knowing that the authorities will try to reconcile a woman with her abuser, rather than punishing him.[130] Two women, who male family members had abused, told Human Rights Watch they would not report the abuse, believing the authorities would not help them, but would instead return them to their abusers.[131]

Part of the problem is the legal guidance itself. According to article 10 of the 2013 law, “priority shall be given to preventive and counseling measures, unless the case requires otherwise.”[132] The 2014 implementing regulations state that one of the goals of the 2013 law is to provide rehabilitation programs with the aim of returning a woman to her family.[133]

This is counter to UN best practice on responding to domestic violence, which recommends that responses prioritize “the rights of the… survivor over other considerations, such as the reconciliation of families or communities.”[134] In non-severe cases, the implementing regulations state a woman should remain with her family, but that the Ministry of Labor and Social Development must obtain a statement or pledge from the abuser and the head of the family that she will be protected from further abuse.[135]

Authorities required abusers to sign pledges as part of the response to abuse before the 2013 law. This proved ineffective, according to activists. In 2008, a woman fled from her home to a shelter in Riyadh, but her father and four uncles came to the shelter, arguing it was shameful for their daughter to remain there. According to a Ministry of Labor and Social Development official, “The [men] made promises and signed papers that made it incumbent on them not to harm her.” After releasing the woman to the men, the ministry learned the family killed her.[136]

Khadija, 42, who covered domestic violence cases as a reporter, said:

It doesn’t make sense to assume that [once] you’ve brought in the guardian who is abusing the woman and make him promise, ‘Oh I am not going to beat her again,’ [then] things are fine and she [can be] signed out to him.[137]

Limited Shelter from Domestic Violence

The Ministry of Labor and Social Development may place a victim of domestic violence, with the victim’s consent, in a shelter without informing or requesting permission from her guardian. But implementing regulations specify that the ministry should take women to shelters only in cases of “severe” abuse and where there is no other family to host her.[138]

Domestic abuse specialists agreed that shelter administrators continue to deal with women within the framework of guardianship, generally attempting to resolve the problem between the woman and her abuser, rather than working to empower her to live independently.[139]

Shelter administrations have different policies for arranging how a woman may leave a shelter.[140] The 2014 implementing regulations state that a woman must be allowed to leave a shelter, not necessarily with her guardian, but “in coordination with her family members in order to receive her.” The shelter staff will encourage her family members to receive her, including, if necessary, by facilitating a reconciliation process.[141] During a woman’s stay in a shelter, she may leave for certain designated activities, but if she does not return at the appointed time, the shelter must immediately inform the police, absolve itself of responsibility for her case and, when there is justification, inform her family members.[142]

According to abuse specialists, shelter administrators generally prefer that a woman leaves in the care of her guardian but, if the guardian is the abuser, often allow her to leave with another mahram.[143] For example, Samar Badawi, whose father abused her, left a shelter in 2009 with the permission of the governor to live with her brother.[144] Another woman, Lulwa Abd al-Rahman, remained in a shelter for at least three years because she did not have permission from a male relative to exit, according to her fiancé.[145]

Other shelters appear to have policies that allow women to leave by themselves rather than into the care of a mahram. Dr. Abeer, a clinical psychologist, told Human Rights Watch that some shelters may “release” a woman on her own if she has finalized any ongoing court cases related to the abuse. She added that it is practically difficult for women to live alone—women still struggle to sign leases without a guardian and may require guardian permission to secure employment—so they may return to their abusers.[146]

As abuse often happens in the context of wider family dynamics, releasing a woman to another male relative other than her abuser does not necessarily ensure her safety. In 2009, Sura, a now-retired university lecturer, noticed one of her students was frequently late or absent. The student told Sura that her father sexually abused her. The student went to a shelter, but the shelter later released her to her uncle, who returned the girl to her father. According to Sura, the student told her that her father threatened her and told her he would kill her if she complained about the abuse again.[147]

Permission to Exit Prisons

Women in Saudi prisons require a guardian to sign them out as a condition of their release.[148] As Dr. Heba explained, “The [authorities] keep a woman in jail… until her legal guardian comes and gets her, even if he is the one who put her in jail.”[149] If a family refuses to take a woman back to their home after she has finished her prison term, she must stay in prison or be transferred to a shelter.[150]

Continued detention following completion of a prison term, including forced stay at a shelter, constitutes arbitrary detention, is in breach of international standards, and is a form of discrimination and a violation of CEDAW.[151]

In November 2015, the Saudi Gazette reported that shelters took in 2,706 women over a two-year period after their release from prison, most of whose families refused to take them home. The paper quoted a legal expert, who stated, “The guardianship of the fathers should be immediately revoked if they refuse to take their daughters back into their homes.”[152]

Wajda, a psychologist, told Human Rights Watch that families often refuse to take back women accused of “moral” crimes.[153] Saudi Arabia punishes individuals for a range of “moral crimes” which criminalize private consensual relations such as khilwa to zina (sexual relations outside marriage). Criminalizing these activities contravenes international standards and these “crimes” are often applied in a manner that discriminates against women.[154]

When women are released into the supervision of their families following “moral” crimes, they may become victims of further violence, including so-called honor killings. Sana, a woman’s rights activist, said, “What is really horrible here is that because of this guardianship system, women can disappear and be buried in the desert and no one will do anything about it.”[155] In July 2009, a man killed his two sisters as they were signed out of a juvenile detention center by their father in Riyadh.[156] According to Elaph newspaper, he killed his sisters after he discovered the nature of their “crime”—being found with two unrelated men.[157]

In late 2015, Saudi Gazette reported that four women “escaped” from a Jeddah shelter.[158] The four women served prison terms for “ethical crimes” and authorities moved them to the shelter after their families refused to take them home.[159] A source told Okaz that a court previously convicted one of the woman of huroob, or fleeing the guardian’s home. After completing her sentence, her father refused to take her home. Authorities transferred her to a shelter. Her brother agreed to receive his sister, but she fled from his house, was arrested, and put back in the shelter. Okaz reported that the shelter exerted “substantial efforts” before the woman’s father agreed to let her marry, that she stayed with her new husband for a few months and then fled. The authorities arrested her and returned her to the shelter. The woman was 19 at the time of her fourth “escape” from a state shelter.[160]

Instead of facilitating women’s ability to live independently, the government appears to be attempting to address this problem by pushing women toward arranged marriages.[161] Six women knowledgeable about abuse cases told Human Rights Watch that authorities try to facilitate marriages for women whose families have refused to accept them following prison terms.[162]

Nada, 26, who was an inmate in a juvenile detention center, said authorities encouraged women to accept arranged marriages and noted that the men involved in these marriages often face difficult marriage prospects, for example because they are non-Saudis or have “dark pasts.” Sowsan, an abuse specialist, said the government will find “bad, random men... that just came out of prison, very dysfunctional men, who use [the women] as concubines.”[163] Nada explained that women are not forced to accept these marriages, but many do, and in such cases a judge steps in to serve as the woman’s guardian authorizing the marriage.[164] According to the six experts, women are then permitted to exit the shelter under the guardianship of their new husband.[165]

Women have the right to refuse to go back to their families or to get married, but are forced to remain in the shelters if they refuse. Shelters often do not allow women to use cellphones, to exit the shelter freely, or to bring their adolescent sons with them into the shelter. Women at a Jeddah shelter reported to the National Society for Human Rights that staff occasionally mistreated women, and that the shelter was overcrowded, had poor facilities and prevented women from continuing their education or leaving the shelter.[166]

Forcing a woman who has escaped abuse by one man to choose between an arranged marriage to another, a life of imprisonment, or a return to abuse is no choice at all; it is a continuation of abuse. In August 2015, a woman committed suicide in a shelter in Mecca. A note, purportedly written by her and circulated on social media, said: I decided to die to escape hell.[167]

V. Restricting Right to Equality in Marriage, Divorce, and Child Custody

When a woman wants to divorce her husband, he can ask for anything [in order] to give her a divorce, even to give up custody. [While] he can … say “you are divorced” through a text message.

—Sura, 62-year-old retired university lecturer, December 14, 2015

Inequality between men and women is deeply entrenched in Saudi marriage practices and creates an environment in which women are susceptible to family violence.

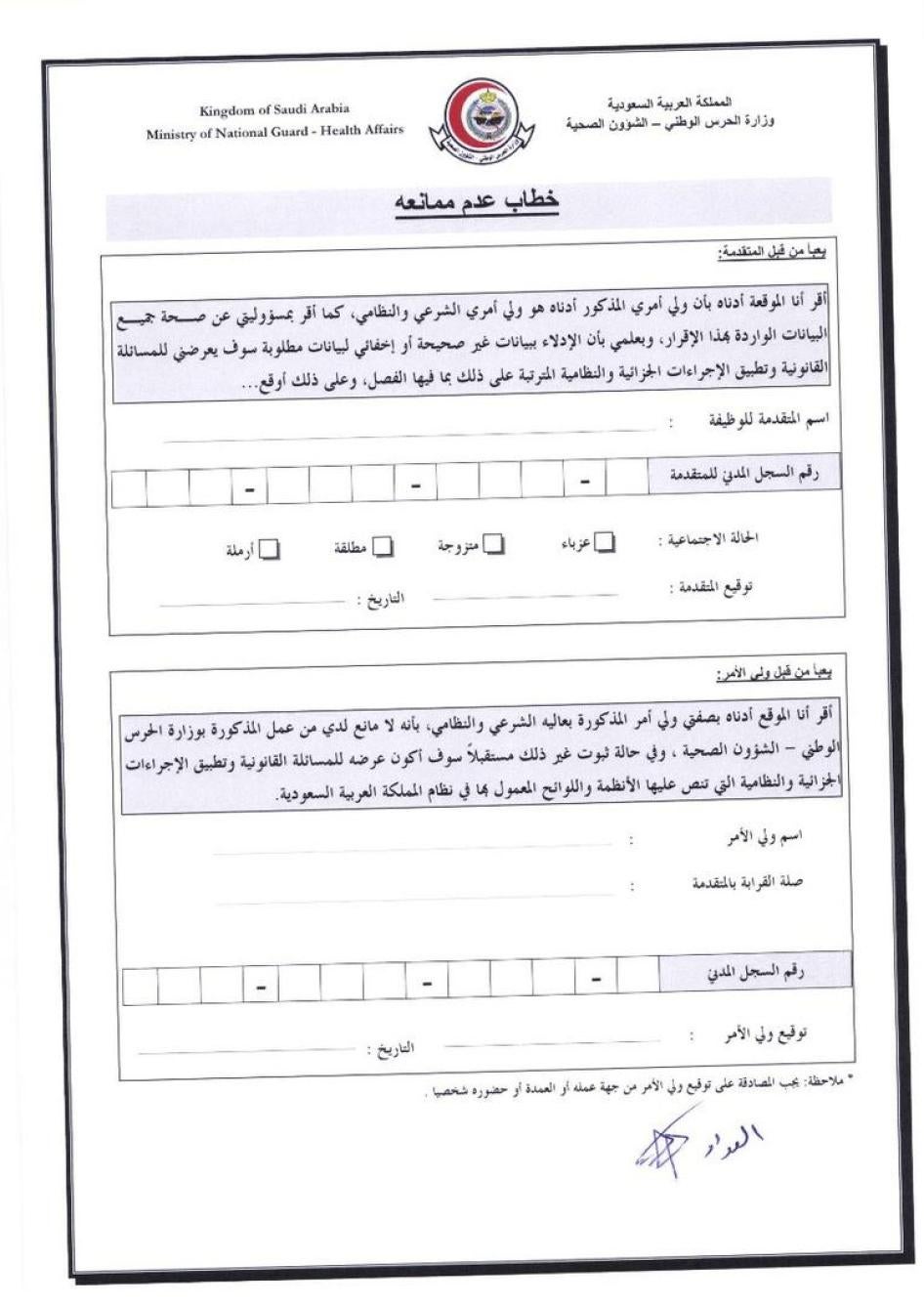

Unlike men, women require their guardians’ permission to get married, and face a more difficult process when seeking divorce. In addition, a male relative may petition courts to forcibly divorce a marriage he deems unfit, and a woman’s husband remains her legal guardian throughout the divorce process, until the divorce is finalized.

While a rising divorce rate has increasingly made these issues a topic of public discussion, Saudi Arabia has failed to pass a law protecting women’s rights in family issues.[168]

Saudi Arabia’s discrimination against women in family relations violates CEDAW, which provides that states “shall take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in all matters relating to marriage and family relations.”[169] In particular, Saudi Arabia violates women’s equal right to freely enter into and to exit marriage and to ensure men and women have the same rights with regard to guardianship of children.[170]

Restricting the Right to Marry Freely

Like many other Muslim-majority countries, Saudi Arabia relies on a personal law system based on Sharia, which treats marriage as a contract concluded by mutually consenting parties. Saudi law has no minimum age of marriage.

Many other countries in the Middle East and North Africa that recognize Sharia as a source of law have set the marriage age at 18 or higher, with some allowing exceptions in limited circumstances.[171] While the Shura Council discussed making 18 the minimum age of marriage along with a package of proposed personal status changes in 2013, no formal rule has yet been passed.[172] Local media continues to carry occasional reports of child marriages.[173]

Child marriage “is any marriage where at least one of the parties is under 18 years of age.”[174] Child marriages violate a host of human rights and have lasting effects beyond adolescence as women and girls struggle with the health effects of becoming pregnant often and when young, their lack of education and economic independence, domestic violence, and marital rape.[175] The UN Committee on Discrimination Against Women called on Saudi Arabia to “prescribe and enforce a minimum age of marriage of 18 years.”[176]

Saudi authorities limit a woman’s ability to enter freely into marriage by requiring her to obtain the permission of a male guardian. A woman’s consent is generally given orally before a religious official officiating the marriage, and both the woman and her male guardian are required to sign the marriage contract. In 2016, the Justice Ministry issued a directive stating women must be provided a copy of the marriage contract.[177] Men are not required to have their male guardian’s consent and can marry up to four wives at one time.

Despite the requirement of women’s consent, forced marriages continue.[178] According to a shadow report submitted by Saudi civil society activists to the UN Human Rights Council in 2013, forced marriages and child marriages are difficult to annul, as women must prove the absence of their consent through “impossible” measures such as not attending the wedding party or not allowing their husband to consummate the marriage.